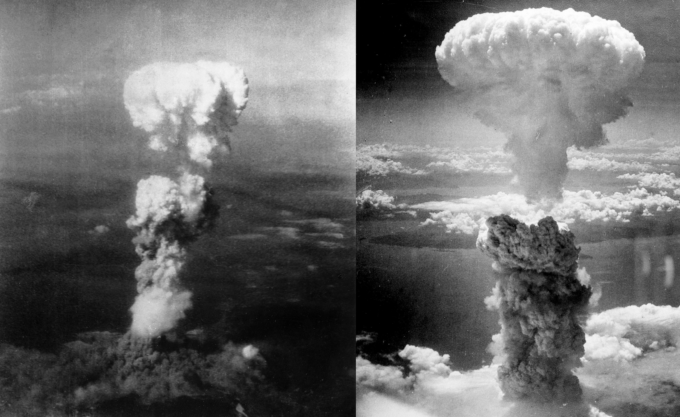

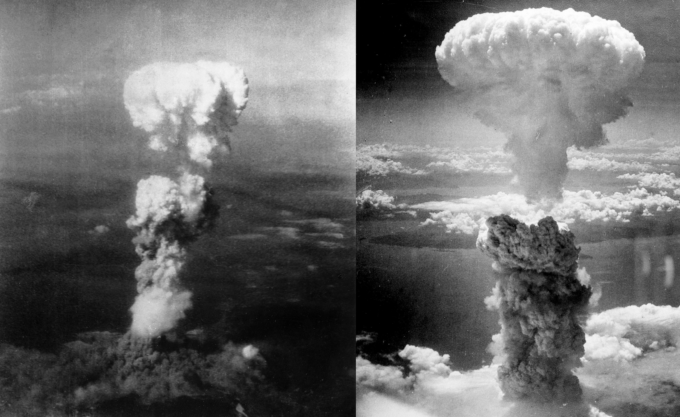

Atomic bomb mushroom clouds over Hiroshima (left) and Nagasaki (right): Wikipedia.

Three Weeks After the first Atomic Bomb Test, They Used It on Two Japanese Cities

Teen physicist Ted Hall, who helped perfect the plutonium bomb, passed its secrets to the Soviet Union hoping to prevent the US from ever using it again. For the past 79 years that courageous act has accomplished what he hoped it would.

Just before sunrise 79 years ago at 5:29 Mountain War Time on July 16, 1945 the Journado del Muerto desert in New Mexico instantly and in total silence flashed as bright as day. As a group of several hundred scientists peered from six miles away at a 100-foot steel tower holding the world’s first atomic bomb, the sky turned brighter than day and the tower and bomb vanished in a brilliant flash of light that erased the stars of the night sky, They were replaced by a fiery turbulent cloud of smoke and dust. A powerful shock wave and the roar of the explosion followed he flash as a mushroom cloud rose 38,000 feet into the stratosphere.

The Nuclear Era had begun with a 25-kiloton bang.

Watching from 20 miles away along with over a hundred-fifty other soldiers of the Army Special Engineering District tasked with guarding the top-secret Los Alamos bomb design and fabrication center was 18-year old physicist Ted Hall. The youngest physicist in the Manhattan Project had significantly helped with the design, testing and success of the implosion system needed to successfully detonate the 3.6” sphere of 13.6 lbs. of plutonium at the core of what was called the “Gadget.”

His job during this first atomic bomb test though, was was to be ready to race off with other soldiers in a bunch of waiting army trucks to evacuate any indigenous residents of the region who might be at risk of radioactive fallout should the winds change from what had been predicted. (As it happened, the winds did shift but Hall and the other SED soldiers were never ordered to make those evacuation runs. As a result, the first nuclear test dubbed “Trinity” by Manhattan Project Director Robert Oppenheimer, which did produce massive fallout to the east of the explosion, wound up causing early deaths, cancers and deformed infants victims in that region. Those native people where the fallout came down were the first victims of the atomic bomb, even predating the Hibakusha — the Japanese survivors of the two atom bombs dropped three weeks later by the US on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.)

Ted Hall, at 18 the youngest physicist hired in January 1944 onto the Manhattan Project right out of his junior year as a physics major at Harvard, recalled in a interview in 1998, a year before his death from kidney cancer, that the Trinity explosion was a “stunning success” but added that he did not share in the jubilant celebration of most of the scientists who had witnessed it. As most of the scientists returned to the Los Alamos “camp” where thousands of scientists and engineers had labored frenetically to develop the bomb, to a day and night of celebrations, Hall said he returned instead to the barracks where he was lodged and listened to some of his 78 rpm recordings of Mahler and Beethoven.

While the huge blast that he had just witnessed was deeply depressing, viewing the awesome power of the atomic weapon he had helped to create hardened his resolve to complete the other job he had been “moonlighting” at in secret since mid-October of 1944 while he was diligently working on the plutonium bomb.

That other job, which he had volunteered for in mid-October 1944, was gathering up all the details he knew about the construction of that bomb and supplying the information to the NKVD, the Soviet spy agency. He was about to provide the full schematics of the bomb and full details about its construction to courier whom he had arranged to meet up with three weeks later, right between the dropping of the Hiroshima “Little Boy” uranium bomb on August 6 and the Nagasaki “Fat Man” plutonium bomb on Aug. 9.

By the time of the Trinity Test, Japan was frantically attempting to get the US to accept a Japanese surrender and an end to World War II in the Pacific. But, as I detail in my new book Spy for No Country (Prometheus Books, 2024) on Ted Hall’s spying and its impact on nuclear history, at the same time, the US was instead trying to delay an end to the violence. Indeed, on the very day of the explosion at Alamogordo, NM, the uranium bomb was being loaded at the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard onto the Navy cruiser USS Indianapolis for delivery to Tinian Island. There the U235 explosive would be placed inside the bomb called “Little Boy” for mission against the doomed city of Hiroshima.

At the same time, a second plutonium bomb, almost identical to the “Gadget” used successfully in the Trinity Test, was being prepared for shipment by air to Tinian in two B-29s to, be assembled there and armed with its plutonium “pit.”

The official US version of the story of the nuking of two Japanese cities remains that the two bombs were deemed necessary by President Truman and his advisers to convince the Japanese to end the war and “save American lives” by avoiding a land invasion. In truth, it later became clear, though it is still not common knowledge among most Americans, that Truman and his military and national security advisors were in no hurry for the war to end as they wanted a chance to test their two new weapons in a real war setting to “send a message” to the Soviet Union and the world that Washington had the atomic bomb and as the only country with it, intended to use it, or threaten to use it, to have its way.

Truman even had his Secretary of State James Byrnes instruct Nationalist Chinese Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek to have his negotiator in Moscow, Soong Tse-wen, who was attempting to reach an agreement with Stalin for a Japanese peace deal, to slow the process down so that the two atomic bombs could be used before the war ended. As I note, thousands of American soldiers, marines, sailors and merchant seamen, not to mention tens of thousands of Japanese, Chinese, Vietnamese, Filipino and other military and civilian people died in that interval between the Trinity Test and the two atomic bombings (which alone killed a quarter of a million people, most of them civilians).

The decision to bomb two populated cities, and to do both by surprise in early morning when people were outside on the way to work, and when children on the way to school, was a deliberate effort to maximize both bombs’ death and destruction.

After Trinity, as it became clear around the “camp” at Los Alamos that the US was about to bomb a non-nuclear nation with its new weapons of mass destruction, Leo Szilard, a top physicist at Los Alamos typed a well reasoned letter to Truman, quickly signed by 70 fellow scientists on the project, pleading with him not to use the bomb on Japan. (Remember, It was a fear that Germany might build an atomic bomb that had led FDR to launch he Manhattan Project, and Hitler’s scientists never came close to building one before the war in Europe ended on May 8, 1945.)

Szilard’s petition was handed to Gen. Leslie Groves, head of the Manhattan Project, who promised to deliver to Truman. He apparently never did deliver it, though Truman was unlikely to have been swayed by it anyhow. (Even the opposition of 5-star Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in WWII, to US use of an atomic bomb on Japan, which he expressed forcefully to Secretary of War Henry Stimson, was ignored.)

Hall was horrified at the destructive power of the atomic bomb. He was also aware as an atomic scientist of the vastly more powerful fusion bombs that by war’s end were being looked into at Los Alamos, Hall had also heard word around Los Alamos that Gen. Gates at a dinner party in March 1944 for senior British physicists working at Los Alamos had told astonished guests that the real purpose of the bomb project was “to subdue the Russians.” This, shockingly, was said even as Russia’s Red Army, after staggering losses, was beating Germany’s crack troops and driving them back to Germany.

Hall, by the summer fall of 1944 had already become concerned that the US would emerge from WWII with a monopoly on the atomic bomb and an evident willingness to use its advantage to maximum effect. He rather presciently decided that the only way to prevent that situation would be to have another country with the bomb, one that would act to prevent that monopoly. He and his friend, Harvard roommate and later courier and co-conspirator Saville Sax, realized early that the only country capable of standing up to a nuclear US would be a nuclear USSR (which it must be noted was a key US ally against Germany and had done the main job of defeating Hitler’s Wehrmacht).

Hall passed his most significant information—many pages of carefully copied drawings and detailed descriptions of the construction of the plutonium bomb—to the American Soviet spy Lona Cohen, shortly after the Hiroshima bombing during a handoff in Albuquerque. She in turn delivered it to the NKVD in the Soviet Consulate in NY which sent it on to Moscow in the diplomatic pouch.

That information convinced both struggling Soviet nuclear scientists and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin to put off efforts to develop a uranium bomb. Instead they decided to focus all available resources in the war-ravaged country on making a copy of the US plutonium bomb used on Nagasaki. They succeeded in testing that copy in the Semipalatinsk desert on Aug. 29, 1949, stunning US scientific and military experts who had predicted such a feat would take the USSR at least a decade.

It was a good thing for the Soviet people (and probably for humanity) that their country got its own atomic bomb when it did. Unknown to Americans, even today, the US, almost immediately after the war ended, had begun working on developing the hydrogen bomb, a nuclear fusion weapon of unlimited destructive power. Even more urgently important, work had begun on how to mass produce fission bombs of the size used on Japan, which at the time were being painstakingly and slowly assembled by hand.

The plan for these new mass-produced bombs, given various names like Broiler, Sizzle, and Shakedown as the number of bombs in the stockpile grew, but eventually called Operation Dropshot, was initially to use 400 of those Nagasaki-sized weapons to destroy 100 cities and other targets in the Soviet Union. Some bombs were also to target cities in the newly established Peoples Republic of China, the Democratic Republic of Korea, the People’s Republic of Vietnam and even major cities in the captive eastern European countries occupied by the USSR after the war and eventually known as the Warsaw Pact nations. During the late 1940s, the target date for this first-strike holocaust was 1954, the year (called A-Day by nuclear strategists in Washington), after which it was assumed that without a preemptive attack, the Soviets would have nuclear weapons with which to retaliate.

Once the Soviets had tested their first bomb in 1949, Washington’s mass murder scheme was thankfully put on indefinite hold, replaced by the Cold War arms race.

Critics will will no doubt say that the young physicist Hall and several other spies, notably the German/British physicist Klaus Fuchs, were traitors worse than America’s Benedict Arnold or Britain’s Mata Hari. But consider the millions of people, mostly civilians of third-world nations who have been killed as a result of US military actions since the end of World War II, and without any nuclear weapons being employed. If seems clear that had the Soviets not obtained their own bomb when they did, their country, and other less developed communist nations, would have likely been leveled to prevent their getting the bomb. Evidence for this view is how close the US came to using atom bombs in 1946 against Soviet troops preparing to move into Iran to claim rights to the oil field across the border from the USSR as promised at the Yalta conference, in 1948 during the Berlin Blockade and in 1954 to stave off capture of the French forces seeking to retake their Indochina colony from the Viet Minh independence forces. Threats to use the bomb against the USSR were made in each case but were not carried out for various different reasons.

Frightening as the Cold War era was (and I personally remember the anxiety back as far as 1955 when I was six!), and as scary as the current situation is with the Ukraine war and US-supplied weapons being used by the Ukrainian military deep inside Russian borders, there has been no use of a nuclear weapon in war since the bomb dropped on Nagasaki on Aug. 9, 1945.

That was the bomb Ted Hall helped design and that he helped the Soviets replicate.

Hall, who was never charged or prosecuted for his spying (long story there, all explained in my book), said he had hoped that if two nations had the bomb, neither would dare use it, fearing to do so would be a murder-suicide act, and that they as a result would ultimately ban it.

That hasn’t happened, although almost all nations of the world have voted to have nuclear weapons banned, and that ban is now part of the laws of war. The hitch is that all nine nuclear nations, including the US and USSR, have refused to sign on to the nuclear bomb ban and the international law has no enforcement mechanism.

Getting those nine nations to join the ban is the task ahead of humanity, and especially of the citizens of the recalcitrant nuclear nations.