In a recent study published in the journal Nature, scientists in the United States report the spillover of the highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 virus in cattle across several United States (US) regions. They further document the detailed symptomatic outcomes of the resulting disease in these bovine populations. Finally, they use a multidisciplinary approach incorporating epidemiological and genomic analyses to highlight that the virus's evolution confers the ability to allow for not only cow-to-cow transmission but also efficient multidirectional interspecies spillover, infecting birds, domestic cats, and even a raccoon in proximity to diseased cattle.

Study: Spillover of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus to dairy cattle. Image Credit: Studio Romantic / Shutterstock

Background

Influenza A virus (IAV) H5Nx is a highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) virus causing widespread respiratory illness and subsequent death in bird populations across Africa, Asia, Europe, and most recently North America. First discovered in China in 1996, the colloquially termed 'bird flu' has since evolved into eight clades and three neuraminidase subtypes, with the H5N1 subtype 2.3.4.4b being its most prevalent and epidemiologically relevant representative.

HPAI H5N1 is alarming, given its potential for spillover (cross-species infectivity). It has been reported to be transmitted from infected poultry populations into wild birds (2002), mammals (domesticated and wild), and even humans (2003). The World Health Organization (WHO) documented 860 human infections and more than 430 deaths since 2003 (fatality rate ~52.8%).

The virus poses significant threats to ecology, economy, and public health, having claimed more than 90 million bird lives in the United States (US) alone. The most recent H5N1-associated morbidity event was that of dairy cattle across Texas (TX), New Mexico (NM), Kansas (KS), and Ohio (OH) between January and March 2024. Understanding the epidemiological and genomic underpinnings of this event may allow researchers to elucidate the etiology (origin) of the disease and prepare for future outbreaks.

Influenza A Virus (H5N1/Bird Flu) Influenza A (H5N1/bird flu) virus particles (round and rod-shaped; red and yellow). Creative composition and colorization/effects by NIAID; transmission electron micrograph imagery is courtesy CDC. Scale has been modified/not to scale. Credit: CDC and NIAID

About the study

The present study documents the January-to-March 2024 morbidity event in American cattle across TX and its neighboring states. It uses a detailed multidisciplinary approach incorporating clinical, epidemiological, and phylogenomic investigations to elucidate the pathophysiology of the virus and the genetic underpinnings of its spillover potential.

Researchers first obtained samples for the clinic-epidemiological evaluation from nine farms across affected states – TX (5 farms), NM (2), KS (1), and OH (1). Notably, the singular farm in OH was affected following the introduction of cattle (assumed to be healthy) from the first affected TX farm.

Data collection comprised nasal swabs, milk, blood buffy coats, and serum (n = 331). These samples were subjected to real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) and viral metagenomic sequencing. Additionally, tissue from birds (great-tailed grackles, rock pigeons) and mammals (cats and raccoons) found dead at infected farms were subjected to rRT-PCR analysis.

Virus-shedding investigations were conducted to elucidate the source and duration of viral transmissions following initial infections. Excised tissues from cows, dead birds, and mammals were subjected to histological examinations. Finally, phylogenomic analyses were conducted to isolate the etiological source of the viral strain and the genetic underpinnings of its substantial spillover.

Study findings

Clinical-epidemiological investigations revealed multiple disease symptoms in cattle, notably decreased feed intake, mild respiratory distress, reduced rumination time, lethargy, dehydration, abnormal feces, and abnormal milk production (20-100% reduction in quantity, yellow color, and thick consistency). Symptoms persisted for 5-14 days. However, milk production remained reduced for up to four weeks.

All investigated rRT-PCR samples positively detected viral load, but virus shedding was the highest and most frequently detected in milk samples and mammary gland tissue. Notably, while virus shedding duration investigations detected viral loads in milk samples on days 3, 16, and 31 post-infection, infectious virus shedding was only observed on day 3.

"Histological examination of tissues from affected dairy cows revealed marked changes consisting of neutrophilic and lymphoplasmacytic mastitis with prominent effacement of tubuloacinar gland architecture which were filled with neutrophils admixed with cellular debris in multiple lobules in the mammary gland. The most pronounced histological changes in the cat tissues consisted of mild to moderate multi-focal lymphohistiocytic meningoencephalitis with multifocal areas of parenchymal and neuronal necrosis."

Phylogenomic analysis revealed that all recovered viral sequences aligned with a novel monophyletic reassorted substrain of H5N1 termed B3.13, first discovered in a Canada goose in Wyoming (25 January 2024). This lineage was most closely related to a sequence obtained from a deceased skunk in NM (23 February 2024). The similarity between viral genomes from investigated farms highlights circulation and cross-infectivity between their inhabitants, likely due to the transportation and introduction of animals between these farms.

Conclusions

The present study highlights the potential of H5N1 viral spillover and cross-infectivity in both avian and mammalian hosts across farms in the US. The mammary gland was highlighted as the region with the highest viral replication, with infected milk representing the most likely transmission route. The novel substrain (B3.13) identified herein is alarming given its spillover potential (to domestic and wild bird populations and even other mammals – cats, and raccoons).

While no human infections were reported from under-study farms, mild infections were reported during the study duration from other farms near the study area, highlighting the virus's zoonotic potential and the potential for a human pandemic.

Protective Measures

According to guidelines from the CDC, it is crucial to wear the recommended personal protective equipment (PPE) when working directly or closely with sick or dead animals, such as animal feces, litter, raw milk, and other materials that might have the virus. The recommended PPE includes fluid-resistant coveralls, a waterproof apron, a NIOSH-approved respirator (e.g., N95), properly-fitted unvented or indirectly vented safety goggles or a face shield, head cover or hair cover, gloves, and boots.

Proper procedures for putting on and removing PPE, such as washing hands before and after using PPE and disinfecting reusable PPE after every use, are essential. Additionally, it is advised to shower at the end of the work shift, leave all contaminated clothing and equipment at work, and watch for symptoms of illness for ten days after working with potentially sick animals or materials.

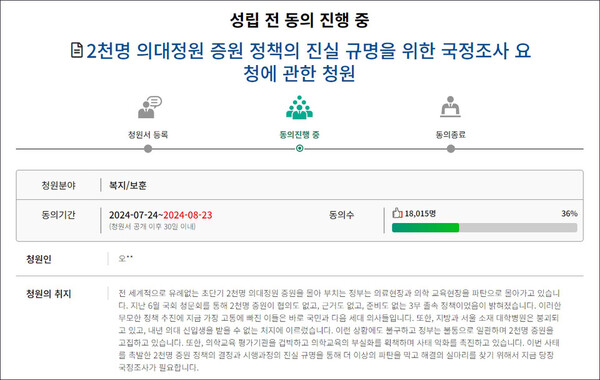

A petition has been filed to request a parliamentary investigation to determine the truth about the medical school enrollment increase policy. (Source: National Assembly petition website)

A petition has been filed to request a parliamentary investigation to determine the truth about the medical school enrollment increase policy. (Source: National Assembly petition website)

On Tuesday, Yoon Sung-chan, president of the Association of Korean Medicine, called for applying actual loss insurance to unreimbursed oriental medicine practices and reimbursing the use of diagnostic devices by oriental doctors in a news conference to mark his 100th day in office at the association headquarters in Seoul. (Courtesy of the Association of Korean Medicine)

On Tuesday, Yoon Sung-chan, president of the Association of Korean Medicine, called for applying actual loss insurance to unreimbursed oriental medicine practices and reimbursing the use of diagnostic devices by oriental doctors in a news conference to mark his 100th day in office at the association headquarters in Seoul. (Courtesy of the Association of Korean Medicine)