Thomas Caygill, Senior Lecturer in Politics, Nottingham Trent University

Wed, July 24, 2024

Flickr/UK Parliament, CC BY-NC-ND

Following the state opening of parliament, the House of Commons has been debating the contents of the king’s speech (referred to as the debate on the address). This unfolds over the course of several days and is effectively a debate on the new Labour government’s legislative agenda for the next 12 months.

During the final votes in this debate, prime minister Keir Starmer suffered his first rebellion as several of his MPs voted against the government (and several more abstained) on a vote to lift the cap on benefits that restricts support to a family’s first two children and no subsequent siblings. The vote was on an amendment put forward by the Scottish National Party, which has called for the cap to be removed.

Since before the election, Starmer and his chancellor Rachel Reeves have insisted that they would like to remove the cap but do not currently have the money to do so.

Want more politics coverage from academic experts? Every week, we bring you informed analysis of developments in government and fact check the claims being made.

Sign up for our weekly politics newsletter, delivered every Friday.

The rebellion was limited to seven Labour MPs and in truth there was very little chance of the amendment passing as the government had a working majority of 180 – and won the vote 363 votes to 103. Nor would the two-child limit have been immediately ended had the vote passed.

However, while small, this rebellion was symbolic. Votes on king’s speech debates are considered to be an issue of confidence because they drill into the heart of the government’s political agenda. The speech is not binding but it sets the tone for what the new government most wants to achieve.

Given the symbolic importance of the vote, Labour MPs were on a three-line whip, which is a strict instruction to attend and vote according to the government’s position. This may go some way to explaining why Starmer suspended the whip from those seven MPs who rebelled. This was a strong reaction to the rebellion, even if suspension is temporary and will be reviewed in six months by the government chief whip. The suspension means that the seven, who include former shadow chancellor John McDonnell and one-time Labour leadership hopeful Rebecca Long-Bailey, will now sit as independent MPs until the whip is restored.

The risks of this approach

There are risks to taking such a heavy-handed approach. The suspension or removal of the whip is considered to be a nuclear option when it comes to party discipline, mainly because the more you do it, the less effective it becomes. A precedent has been set in this case so when bigger rebellions come – and come they will – Starmer could run into problems. It would not be practical to suspend the whip from dozens of MPs.

That being said, there are those who will argue that the leadership wanted to send a message that dissent, particularly on important votes, will not be tolerated, even if Labour has a substantial governing majority.

The seven MPs who have been suspended are also from the left wing of the party and they already have an uneasy relationship with the prime minister. They are likely to be a rebellious bunch during the course of the parliament.

But the same rules apply in reverse, too. Rebelling against the whip is an action of diminishing returns as much as suspending people for rebelling. If you become a serial rebel, the government will just write you off as such and be less willing to pay attention to your concerns. Keeping rebellions to a minimum and only to the most important and consequential of issues is more likely to make the government sit up and listen to your concerns.

So there are multiple moving parts here in terms of how the rebels and whips continue to behave which will be interesting to watch over the course of this parliament.

What happens next?

In all likelihood, Labour will at some point remove the two-child benefit limit. A key part of its manifesto is to reduce child poverty and a large number of charities and thinktanks have highlighted the negative impacts of this policy in particular in that respect.

Read more: I research poverty in the UK – the two-child benefit limit is causing real and lasting harm

This of course raises the question of why, therefore, there was no pledge to end the cap in the king’s speech and why Starmer came down so hard on the rebels in this vote. The answer to this comes lies in the government’s iron-clad rules on spending commitments, which give it limited room to manoeuvre on tax and spending. The removal of the two-child limit will cost £3.4bn a year, according to the respected Institute for Fiscal Studies.

We might see some movement in the forthcoming budget (expected in the autumn), given the strength of feeling in the party on the issue. A lot of MPs feel strongly about this and have raised their concerns with the whips and cabinet, even if they didn’t rebel against the whip in this vote. That’s an alternative approach in trying to influence the government privately and may yet prove influential. Both in terms of the policy itself and the future of the seven suspended MPs, we should watch this space.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Thomas Caygill is currently in receipt of a British Academy/Leverhulme Small Research Grant for research on post-legislative scrutiny in the Scottish Parliament and has previously received funding from the Economic and Social Research Council.

Keir Starmer needs to answer these pressing questions about how he will govern

Geoff Mulgan,

Fri, July 26, 2024

Keir Starmer’s government has hit the ground running. But over the next few weeks and months some serious choices will have to be made about exactly how to govern. These are 13 pressing questions that will demand answers soon, partly drawing from my experience working in city government, several national governments (including the UK, where I ran the strategy unit and was head of policy in No.10 under Tony Blair) and the European Commission.

The new prime minister and cabinet secretary will need to drive up performance in Whitehall departments. That might require reviving capability reviews and importing the role of public service commissioners from Australia to keep the civil service on its toes.

There’ll also be a need to rebuild the training system which has largely collapsed, perhaps with a new college of government, not just for officials but also for ministers.

2. Who will be the fixers?

Tony Blair built up a strong No 10 and Cabinet Office, with strategy and delivery units and more (I ran the performance and innovation unit before the strategy unit). Starmer now has huge power and patronage but needs vehicles to project that power. He will need central teams able to anticipate and fix problems, to drive strategy and handle difficult events. His predecessors lacked these capacities, and it showed.

3. Do ministries need reorganising?

Next, Starmer has to decide on reshaping ministries. Whitehall usually exaggerates how much this kind of structural change achieves and, for now, Starmer has decided to leave the departments intact. But in time he will need to fit the forms to the functions.

That said, the one restructuring which many policy experts advocate – separating the Treasury’s public spending and economic policy roles (as almost every other country does) – isn’t going to happen anytime soon.

4. What’s the strategy for talent?

The government will need a strategy for talent. It’s already brought in talented outsiders as ministers and will need to bring in many more to refresh Whitehall. Getting the right people into the right jobs is key to achieving results – and not running out of steam.

Starmer spoke a lot about “missions” during his election campaign and we can expect an aerosol of “mission” titles in boards and committees. But some subtlety will be needed. Missions in health are very different from ones in economics, crime or the environment.

A mission delivery unit has been proposed to ensure departments are delivering, but this may also have to be re-thought. Combining short-term performance management with long-term strategy in this way tends not to work for long, since they require very different methods and mindsets.

6. How will Great British Energy actually work?

Labour has committed to a series of new public institutions (Great British Energy, a national care service, a national wealth fund and Skills England) but has so far offered little detail.

The national wealth fund has turned out to be little more than a label, but GBE will be set up fast and government will have to decide whether to use any of the methods that have transformed business or the best governments globally over the last decades. The huge impact of data, algorithms and platforms on so much of contemporary life isn’t yet reflected in the plans for new institutions.

7. What styles of government will be used?

Will Starmer’s government use the new, often quite draconian, powers governments have taken over the last decade in its operations (such as so-called Henry VIII clauses)? Should there instead be distinctive approaches, for example by cutting the cognitive load for citizens? Much recent policy has done the opposite, with ever more baroque tax and welfare rules, for example.

8. How can we modernise public finance?

A critical issue will be to modernise public finance methods – how budgets are set and implemented. The immediate concern will be to keep a grip on the public finances and boost private investment. But in the medium term the government needs to update Whitehall’s methods, which are out of date and ill suited to its priorities, whether in relation to longer-term investment in people (investment methods are used for buildings but not for education, health or R&D) or use of data to learn about the impacts spending achieves.

For a cash-strapped government, creative approaches to efficiency will also be vital. A new “office for value for money” has been promised, but nothing has been said about how it will work.

9. How do we get local government out of dire straits?

Stabilising finances for struggling local governments will be a first priority, with fundamental reform long overdue. But better answers will also be needed on how to organise collaboration with local authorities and devolved administrations, getting beyond Whitehall’s various competitive bidding systems which so badly failed on levelling up.

Periodic meetings of both national and local leaders have been offered in the first few days of the new government. But a shared bureaucracy is also needed. Coordinating efforts at a local level will be vital for many of the government’s priorities, from housing to care.

10. How can digital functions be updated?

Digital operations matter hugely to modern governments. The GOV.UK site is relatively useable, but the UK has arguably fallen well behind the world’s best. Starmer has decided to concentrate responsibility in one department, but elsewhere central teams have done best, for example in radically simplifying payments, authentication and services. Learning from front runners like Estonia and India would be helpful here.

Sorting out AI procurement could deliver big gains, but rhetoric is far more visible than results, and there’s a risk of repeating the tech “solutionism” that created past disasters like Horizon .

11. How can the public sector experiment?

Top-down policies will only go so far. Just as important will be ideas on how to organise experiments and innovation across the public sector, including mobilising local ingenuity and social entrepreneurs on issues like homelessness and mental health. This continues to be organised in arguably very fragmented, underfunded and ad-hoc ways compared to innovation in fields like pharma. But it could be vital to success in a second term.

12. How can the government make better use of its own data and evidence?

Starmer has committed to doing what works. But this will require fresh thinking on how to bring together data, statistics, analysis and evidence in more coherent ways so that government actually knows what is working. Shared intelligence could be a guiding principle for the new government.

13. How can business and charities be brought in?

The new government will soon need to work out how to partner with business. Before the election it was all about wooing and reassuring. Promises of sanity and stability are good starting points. But now more structured partnerships are needed, on issues like employee mental health, financial inclusion and decarbonisation.

There’ll be a parallel need to reframe the government’s compact with civil society, again with a two-way deal, focused on a few priorities such as acute hardship.

Want more politics coverage from academic experts? Every week, we bring you informed analysis of developments in government and fact check the claims being made.

Starmer is right to emphasise that how things are delivered matters as much as what is decided. And he is right to warn against sticking plaster solutions – though some of the most urgent crises such as in Thames Water or local government may demand sticking plasters.

Before long he will need to start thinking about a more radical agenda for change, ahead of the next election. But for now, the priority is restoring sanity and competence. For that, he needs to recognise that the British state is not a Rolls Royce just waiting for a new driver to steer it in a new direction. Instead, it needs a thorough overhaul, and soon.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Geoff Mulgan works part-time for IPPO, the International Public Policy Observatory, which receives funding from the ESRC. He is also on the advisory board of Labour Together.

Keir Starmer’s Clash With Labour Left Sets Up Wider Fight on Tax Rises

Alex Wickham, Joe Mayes and Ellen Milligan

Sat, July 27, 2024 at 3:07 a.m. MDT·5 min read

(Bloomberg) -- UK Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves will run the gauntlet between the left of her Labour Party and opposition Conservatives on Monday when she outlines the state of public finances.

In a speech setting the tone for the Britain’s economy and its politics for the next five years, Reeves is expected to say she’s inherited a near £20 billion ($26 billion) shortfall for public services from the Tory government ousted by Labour in this month’s landslide election win.

That black hole provides the backdrop for her first budget in the autumn, when she’s told Bloomberg “difficult decisions” will have to be made. Whether she and Prime Minister Keir Starmer respond with tax rises or spending cuts, the Tories and the Labour left are poised to pounce.

It’s a tricky balancing act, and weeks of internal deliberation have taken place about how to get the speech right, people familiar with the matter said. Starmer has used the first three weeks of Labour rule to blast its “shocking” inheritance from the Tories in areas from crime to migration, but it’s harder for Reeves to feign surprise at the fiscal picture given the open books provided by the Office for Budget Responsibility.

The scale of the challenge “has been evident for some time,” according to Ana Andrade and Dan Hanson at Bloomberg Economics. They concur that some £20 billion needs to be found by 2028-29 to prevent spending cuts in unprotected departments such as justice and local government. Pressures on defense outlays, public sector pay and welfare could see that rise higher still, they wrote, meaning “more tax hikes look inevitable.”

That’s problematic for Reeves and Starmer, who spent the election campaign repeatedly promising they had “no plans” to raise taxes beyond a select few, including on private schools, non-domiciled residents and windfall profits for oil and gas companies.

The Financial Times reported that the chancellor will delay various “unfunded” projects for new road links and hospitals to make up the financial shortfall.

Indeed, the chief concern of advisers working on the speech is to maintain Reeves’s credibility. There is broad agreement on the strategy of shining a spotlight on the Conservatives’ record, blaming them for dire public finances and any unpopular decisions Labour might have to make — inspired by former Tory Chancellor George Osborne’s approach after the financial crisis.

Yet aides have also stressed the need not to go overboard and claim the public finances are far worse than thought when Reeves told voters she wouldn’t put taxes up. Indeed, she admitted in the election campaign that she wouldn’t be able to act surprised at what she found.

Some officials argue Labour can’t announce sweeping tax rises right away to fund spending demands from the wider party.

That’s what the Tories want Labour to do, a party official said, because the opposition would then spend the whole Parliament accusing them of lying in the election campaign. Party strategists think Tory warnings about Labour tax rises could be one reason for the July 4 result being closer than opinion polls suggested, and Reeves would not want to confirm those suspicions among swing voters, another aide said.

Yet holding the line is not proving easy. Starmer and Reeves find themselves buffeted by pressures from their party to spend more on public services and fund it by raising taxes on the wealthy.

Asked at a Group of 20 meeting in Rio de Janeiro on Thursday whether she still had “no plans” to raise taxes on wealth, property or inheritance — as Labour repeatedly said during the election campaign — Reeves failed to reiterate that commitment.

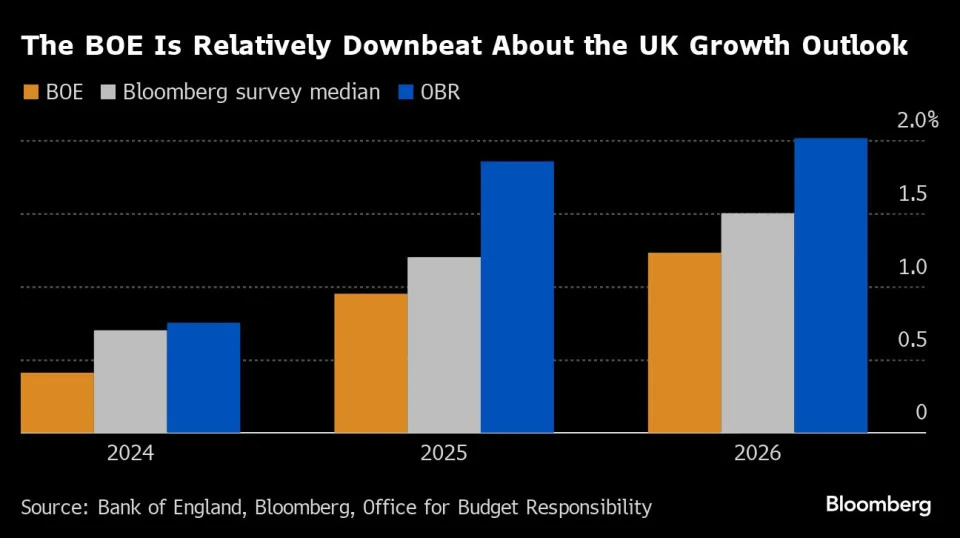

An added risk is if the OBR downgrades its growth forecasts to bring them closer to those of the Bank of England and commercial banks. That would further deplete Reeves’s headroom, giving her less scope to raise spending.

While she could in theory borrow more in the short term, that would come at the risk of economic credibility. Moreover, she’s promised to adhere to fiscal rules meaning debt as a percentage of gross domestic product must start to fall within five years. She’s described them as “iron-clad,” so any change would suggest her promises are paper thin.

The internal party context of the chancellor’s speech is a parliamentary clash on Tuesday between Starmer and left-wingers. After seven members of Parliament voted for an amendment calling for more generous welfare payments for parents, the premier responded ruthlessly, kicking them out of his party for six months.

Scrapping the so-called two-child cap on family aid has become an early cause of the left, and many others across Labour also want Downing Street to act. That would cost at least £2.5 billion, according to the Resolution Foundation think tank.

Starmer’s allies insist they are relaxed about internal discussion and dissent, arguing this small group of MPs had gone beyond that and were acting in bad faith trying to undermine the Labour government.

An aide pointed to the example of Faiza Shaheen, a left-winger replaced as a parliamentary candidate by Labour at the election who then decided to stand as an independent against the party. That showed moves by the left against the party’s interests could not be tolerated, they said.

Still, the row led some ministers to privately suggest the premier had been heavy-handed. It risked creating a bigger fight with supporters of left-wing former leader Jeremy Corbyn down the line, one minister said, predicting some rebels could team up with the Green Party and independents who won seats from Labour at the election on issues like Gaza and arms sales to Israel.

Another aide suggested Deputy Prime Minister Angela Rayner, already seen as sidelined by Starmer, would struggle to support her boss in many further fights with the left.

The next flashpoint on the benefits cap is the budget, ahead of which Labour MPs plan to privately lobby Reeves to signal she will scrap it this parliament. They’re hoping she’ll raise the cap to three from two children initially, or commit to end it before the next election.

Making the numbers add up while keeping her tax promises is the unenviable task that’s been top of Reeves’s mind ahead of Monday.

--With assistance from Ailbhe Rea, Tom Rees and Philip Aldrick.