Yazhou Sun

Wed, Jul 31, 2024

(Bloomberg) -- Chinese national Luo, 23, was thrilled when he was accepted into Cambridge University’s electrical engineering PhD program in 2021.

All he needed before starting was clearance from a UK government agency that vets postgraduate students who study topics that could have military applications. Luo considered that a formality, he told Bloomberg in an interview, considering he’d already been green-lit for his masters degree at the same school.

But he was rejected. So he applied again, and was rejected again.

The agency that reviewed his application — the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office — gave no reason. But since Luo couldn’t fathom being considered a security risk, he applied 14 more times over the next two years while enduring Covid-19 lockdown from his hometown in Sichuan, tweaking the applications to what he hoped would be seen as less sensitive subjects each time to no avail, before switching his research to a field not covered by the FCDO’s vetting process.

“I was on the edge of a breakdown that whole time,” said Luo, who asked to be identified by only his surname for fear that his student visa might be revoked. “If the UK government has doubts about us, why do universities give us offers at all?”

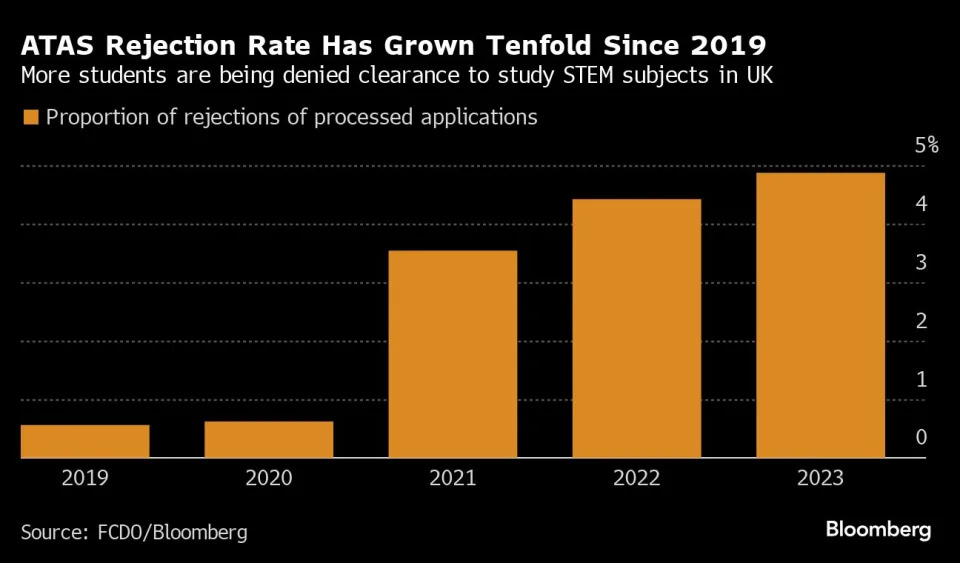

Luo said he believes he was caught in an escalating UK campaign to “de-risk” higher education, following warnings from British security agency MI5 that universities are “magnetic targets for espionage and manipulation” by hostile foreign states. Since its inception, the FCDO’s vetting process, the Academic Technology Approval Scheme, has kept thousands of foreign students out of UK higher education, with the rejection rate increasing almost tenfold over four years. Students from China, which sends the most international students to the UK, represent a large portion of ATAS rejections, according to interviews with applicants and university professors and rejection emails reviewed by Bloomberg News. The apparent crackdown has swept up students who say they’ve been unfairly maligned as potential spies and exacerbated universities’ funding crisis. Chinese students are a key source of revenue for UK universities, contributing an estimated £5.4 billion on tuition and other expenses in 2021, according to the British Council. The “de-risking” strategy is also reducing international research collaboration, an indicator often used to measure academic excellence.The UK government and its allies have pointed to a long history of alleged economic and cyber espionage by China. Last year, a joint statement by intelligence chiefs for the UK, US, Canada, New Zealand accused China of trying to steal intellectual property in sectors including robotics, biotechnology and artificial intelligence. But some business leaders and academics worry the response has been too heavy-handed, lacks transparency and jeopardizes the UK’s tech and science talent pipeline. The Chinese government has repeatedly denied accusations of intellectual property theft. “China has always encouraged and supported educational cooperation based on friendship, mutual trust and mutual benefit, and firmly opposes the politicization of normal study abroad and educational exchanges,” said a spokesperson for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.A representative for the Chinese embassy in the UK added that Chinese students are “hardworking and diligent” and that any restrictions on them are “unreasonable and unacceptable.”

The battle for technological supremacy between China, the US and allies is increasingly bleeding into higher education, with similar measures being applied across the US, Europe and Australia. Last month, Robert-Jan Smits, the president of a top Dutch technical university that feeds talent to chip giant ASML Holding NV, called out US officials’ questioning of the institution about its intake of Chinese students, Bloomberg News reported.

“Over-regulation of security in relation to international cooperation in research is not only associated with individual cases of discrimination,” said Simon Marginson, director of the Oxford University-based Centre for Global Higher Education. “It harms science and innovation in the West.”

An FCDO spokesperson said that ATAS is “a thorough, necessary and proportionate tool to protect UK research from misappropriation and divergence of sensitive technology to military programs of concern.” The vetting process is “country agnostic” and there is an appeals process, the spokesperson added.

Tenfold Increase

When the UK government launched the ATAS program in 2007, it was intended to screen out individuals who might use their research in the UK to develop weapons of mass destruction, following MI5 warnings that al-Qaeda’s terror network was seeking to recruit university students. In 2020, it was expanded to include all advanced military technologies, casting a wide net around subjects including physics, mathematics, engineering and artificial intelligence.

Students and researchers from the US, the European Economic Area, Switzerland, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Australia, Canada, New Zealand — the UK’s political allies — don’t need clearance. Those from other countries need to apply. Students from China make up about 22% of international students in the UK, the largest group of any country, followed by India (19%) and Nigeria (6.5%), according to higher education data provider HESA. The expansion of ATAS coincided with rising economic tension with Beijing, which has seen the US, UK and allies impose a range of trade restrictions on China. This has been coupled with warnings from the British government about the risk of foreign states targeting sensitive research, with a parliamentary committee stating in 2023 that universities “provide a rich feeding ground” for China to achieve political influence and economic advantage over the UK.

Against this backdrop, the ATAS rejection rate has shot up nearly tenfold: from 148 out of 26,269 applications processed in 2019 (about 0.6%) to 1,683 out of 34,528 applications processed in 2023 (about 4.9%), according to FCDO statistics, obtained by Bloomberg News via a freedom of information request. The FCDO said that when you include duplicate and incomplete applications, the rejection rate was about 3.5% in 2023.

The FCDO said it doesn’t disclose the nationalities of those it rejects for fear of prejudicing diplomatic relations. Online forums and social media groups reviewed by Bloomberg indicate that Chinese students have been a large part of the rejections.

At least three student-organized groups on WeChat, a Chinese social networking app, have emerged for applicants who have been rejected or haven’t heard back about their ATAS clearance for the 2023/2024 school year. The groups, with 500 members each (the maximum allowed), see students gripe, commiserate and strategize next steps. Bloomberg reviewed several of the group members’ ATAS rejection emails.“You may be an innocent Chinese researcher,” said Charles Parton, a former UK diplomat who spent the bulk of his career focused on China and is now a fellow at the Council on Geostrategy, “but the UK has a duty to defend itself.”“Sadly, there will be collateral damage,” he added.

The FCDO declined to comment on the vetting criteria or how it measures the success of the program. There are recurring themes in rejected students’ accounts: degrees at China’s military-linked universities, funding from the Chinese Scholarship Council, a government body; and a research focus in aerospace, materials science, telecom and quantum technology, according to hundreds of messages reviewed by Bloomberg and interviews with eight students.

“There are always certain areas where you don’t want open engagement,” said Marginson, “but the broad brush nature of this policy is picking up far too many cases.”

The scrutiny of Chinese STEM students in the UK follows a similar clampdown in the US.

In 2018, the Trump administration launched the “China Initiative” to counter economic espionage by Chinese researchers. The sweeping program prompted thousands of FBI investigations but yielded more wrongful arrests than spies. Although the plan was scrapped by the US Justice Department in 2022, the targeting of Chinese students has not gone away. At least 20 Chinese STEM students with valid visas have been denied entry to the US since September, spreading confusion and fear across campuses from the University of Virginia to Yale University, Bloomberg News reported.

In an unprecedented transatlantic joint address in 2022 with FBI director Christopher Wray, MI5 head Ken McCallum said vetting reforms had resulted in 50 students, whom they linked to China’s People’s Liberation Army, leaving the UK. The British security agency declined to comment further on the circumstances of the students.

Three months after the joint speech, London’s Imperial College shut down two major research centers sponsored by Chinese aerospace and defense companies, the Guardian reported, citing confirmation from the university.

Imperial did not respond to several requests for comment. An Imperial spokesperson previously told the Guardian that all of its collaborations are thoroughly scrutinized, “in line with our commitments to UK national security.”

Collateral Damage

The sharp uptick in rejections and lack of clarity on the ATAS criteria has alarmed some academic supervisors seeking to fill places on their research programs, according to interviews with several professors across UK campuses.

“Every ATAS process is grueling,” said Mingwen Bai, Assistant Professor of Materials Engineering at Leeds University whose prospective PhD candidate’s ATAS status had been pending for three months. “There is no transparency.”

PhD programs are typically fiercely competitive and professors want to choose the strongest candidates who can produce high-quality research papers – a necessity for professors’ future funding. But with ATAS rejections on the rise, professors increasingly have to debate between giving offers based on merit or chances of ATAS clearance.

“You’d have 600 students fighting for that one PhD spot with scholarship,” Bai said. “When your student gets rejected, you lose one researcher, and you can lose that project and the funding. This is detrimental to the talent pipeline.”

The rejections exacerbate the funding challenge of UK universities, which have become heavily reliant on Chinese money, particularly since annual tuition for domestic students has been capped at £9,250 since 2017. This contributes to losses of about £2,500 per student per year, according to an analysis by Russell Group, an association of the UK’s top research institutions.

To make up the shortfall, British universities have courted international students, who pay fees up to four times higher than domestic students. Chinese students contributed more than 50% of postgraduate income at 15 of the 24 Russell Group universities, according to DataHe, a provider of higher education data.

Reduced International Collaboration

On top of talent and tuition fees, China also provides funding for research, although this is also under increasing international scrutiny. China has matched hundreds of millions of pounds in funding from UK Research & Innovation, a government agency that spends taxpayers’ money on science and technology R&D. The collaboration has yielded 804 joint projects and 10,490 scholarly publications.

International collaboration is broadly considered to advance academic research and is often used as a metric in rankings of top universities. But as the UK government’s scrutiny of Chinese researchers has increased, joint research has started to taper.

Prior to 2022, the number of UK research papers co-authored by Chinese colleagues had been steadily rising for two decades, but in 2023 that number fell by 2%, according to analytics firm Clarivate’s Web of Science data.

If the trend continues, it could create problems for businesses, said Russ Shaw, founder of Global Tech Advocates, a community of business leaders and investors focused on developing tech ecosystems. “Freedom of talent brings knowledge transfer,” Shaw said. “We can’t do it on our own in isolation.”

William Wu, the founder of ZeroAI, a Liverpool-based startup that develops software for autonomous vehicles, said that Chinese students have made significant financial, intellectual and academic contributions to the UK.

“At a time when the UK is trying to build up trustworthy AI, getting rid of the top talent is very unwise,” he added.

Luo said he’ll most likely go into climate consultancy post graduation, where the salary would be half of what he could make as an engineer. “Whenever I think about the last couple of years, I just want to cry,” Luo said, adding that he gave up full scholarships at top universities in Hong Kong and China to go to Cambridge. “I always wonder if I made the wrong choice.”