Multi-polarity: A new alignment?

First published at Against The Current.

The crisis of globalization has created growing national tensions. No longer do we hear about the wonders of global free markets and world integration. Instead, talk has turned to “decoupling” from China, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and multi-polarity breaking up imperial Western leadership.

As multi-polarity grows, there are some who see this as a new stage of non-alignment, and even the creation of an anti-imperialist bloc. But the economic and political elites of the Global South are too deeply tied to transnational capitalism to be truly independent. Instead, multi-polarity is a struggle within global capitalism for a larger share of markets, profits and political power.

China has become the main proponent of a new world order based on “win-win” relationships. But a “common destiny for mankind” within global capitalism covers over the fundamental reality of capitalist competition and exploitation.

At the core of discontent have been the growing class disparities in the United States and Europe, creating a crisis of legitimacy for capitalist elites. And in the Global South, historic imperialist inequalities are clashing with the growing power and demands of the southern-based transnational capitalist class (STCC).

Some see this as a progressive new nonalignment. But the southern contingent of the transnational capitalist class (TCC) is far too integrated with northern capital to pursue nonalignment as some truly independent bloc. Whereas the Western working class wants out of globalization, the STCC wants further in.

After World War II a great wave of anti-colonial struggles swept what was then called the Third World. The period produced various political leaders from communists like Fidel Castro and Ho Chi Minh, to radical socialists such as Kwame Nkrumah and Nelson Mandela, and anti-colonial nationalists like Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser and Iran’s Mohammad Mosaddegh.

During this time the oppressed national bourgeoisie joined with the masses of workers and peasants in the struggle for independence and self-determination. But those days have come and gone.

Non-alignment or integrated capital?

The southern bourgeoisies long ago cut their populist ties and socialist rhetoric to join global capitalism — but not as subservient compradors. Rather, the most successful and powerful have become a contingent of the TCC.

As Bank of America reported, the BRICS (originally Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) combined gross domestic product surpassed that of the Group of 7 (G7) in terms of purchasing power parity.1 And by 2028, the BRICS should account for 33.6% of global output, compared with 27% for the G7.2

In 2021, outflows from the Global South were 26% of world foreign direct investments (FDI), and had climbed to 21% of total FDI stock. This is the material basis for the STCC. In fact, 45 of the top 100 financial holding companies are in the Global South,3 as well as 21 of the 100 largest TNCs.4

We can also examine the regional size and wealth of TCC contingents. Among the 3,194 global billionaires, 34.7% are in Asia, Africa, South America and the Middle East; together they hold 34% of billionaire wealth.5

The five top countries with billionaires are the United States, China, Germany, United Kingdom and India. Among ultra-high-net-worth individuals (between $30 million and $999 million), 32% are in the Global South with 30% of the wealth.

Because data for Asia include Japan, the actual totals would be a few percentage points smaller. But, overall, it’s evident that the big bourgeoisies of the Global South are an important contingent of the TCC.

It’s also important to understand that this accumulated wealth doesn’t stand alone in some type of Global South silo. Rather, it is largely integrated with Northern capital through stocks, mergers, joint ventures and a plethora of financial devices. It’s not the 30% of Global South capitalists versus the 70% of Global North capitalists.

To examine how integrated global capitalism has become under TCC direction, a key study by the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology needs to be considered. Its research group traced ownership of transnational corporations, examining a database of 37 million companies and investors.

The study focused on shareholding networks, and a core group of 147 predominantly financial institutions. Situated in these financial institutions were 47,819 individual and institutional shareholders from 190 countries holding principal positions within the world’s largest transnational corporations. In other words, the TCC living in countries around the globe invest their wealth through world-spanning financial firms that hold positions of power in the 15,500 biggest companies.6

An excellent example is the world’s largest asset holder ($9.4 trillion), U.S.-headquartered BlackRock. In 2022, it announced that foreign investors are the majority of its new clients.

Among BlackRock’s top 10 investors are the sovereign wealth fund China Investment Corporation, Mizuho Financial group from Japan, the Singapore state investment firm Temasek Holdings, and Wellington from Boston. In turn, Wellington has 2,200 clients from over 60 countries.

An example of a smaller financial institution, but nonetheless rooted in integrated transnational finance and investment, is IFM Investors based in Australia. Much smaller than BlackRock, with assets just short of $200 billion, the firm invests on behalf of more than 640 institutions worldwide, including pensions, insurers, sovereign wealth funds (SWF), universities, endowment funds and foundations.

The fact that BlackRock, Wellington and IFM are headquartered in the United States and Australia is secondary to their representation of TCC investors. Finance capital is integrated global capital, from the largest to smaller-sized firms.

Daimler Truck Holding AG is an instructive illustration of how finance impacts industrial manufacturers considered “national champions.” Daimler Truck has 823 million outstanding shares held around the world. Mercedes-Benz Group is the largest individual shareholder, but other major shareholders include Chinese BAIC Group, the Chinese investor Li Shufu, and the Kuwait Investment Authority, which is also a major holder of Mercedes-Benz shares.7

This example of co-invested Southern and Northern TCC contingents is common. On the production side of the picture, take Procter & Gamble with its 50,000 direct suppliers, each of which may use hundreds of other companies for parts. Such complex world-spanning relationships are common among transnational corporations (TNCs) and tie together the South and North.

Nor are sovereign wealth funds exempt from transnational financial relations. Although SWFs are state-owned and based on national capital, they are a major avenue of global investments.

The example of Norway’s Norges Bank Investment Management is instructive; it holds $1.3 trillion in assets with stakes in 9,228 companies spanning 70 countries.8 Among the top 16 holdings of Singapore’s Temasek are five from the United States, four from China and two from India, as well as the Netherlands and UK.

To appreciate the study by the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, we need to consider how financial institutions function as organizational centers for transnational capital. Banks, asset managers, private equity firms, currency traders and numerous other financial institutions create thousands of different investment vehicles.

These are various ways to organize and invest capital, attracting transnational capitalists the world over. As capital is centralized into various funds it flows out to countries in every continent. It goes into stocks, bonds, equities, futures, real estate, money markets, venture capital (and on and on), making profits off the labor of working people, as well as from purely speculative activities.

The surplus value is re-centralized into these financial firms and distributed back to TCC investors until it’s re-circulated once again. This is the essential process as revealed in the Swiss study, and what we see in BlackRock and other financial institutions.

This is clearly evident in U.S. corporate equities, about 40% of which are owned by foreign investors. Middle-class U.S. households own around 30%, mainly through retirement accounts, and five per cent are held by NGOs. Wealthy U.S. investors hold about 25%.

Since we are interested in decision-making power, we need to discount the millions of small households. As a single national group, U.S. capitalists have the largest holdings. However, collectively foreign transnational capitalists hold the greatest total amount of U.S. capital stock.9

Historic inequalities

Taken together the above data point to why nonalignment is not possible, but limited to a set of inequalities linked to the historic hold Western imperialism has had on the global system. The so-called move to nonalignment is actually meant to bring about closer alignment and greater equality among capitalists, rather than a bloc of neutral powers.

Although the past 40 years have seen the construction of transnational capitalism, it has been established on the body of the older imperialist system. As the STCC has grown stronger its demands for fairer representation in transnational governance institutions such as the United Nations, International Monetary Fund and World Bank have also grown.

There are also other inequalities, such as the environmental burden and dominant position of the dollar in trade and finance. A greater balance of power would help broad sectors of the world’s population — but the biggest winner will be the STCC.

For example, the de-dollarization of world trade (still far from any significant change) would mainly serve to increase the market power of the STTC. It may also create greater political room to avoid U.S. sanctions, which have hurt millions of people throughout the Global South.

Demands that de-center Western state power should be supported, particularly those that benefit the broad masses of people. But we must also be mindful of how these changes create a more powerful Southern bourgeoisie in a better position to exploit labor, buy more military equipment and consolidate its hold on the state.

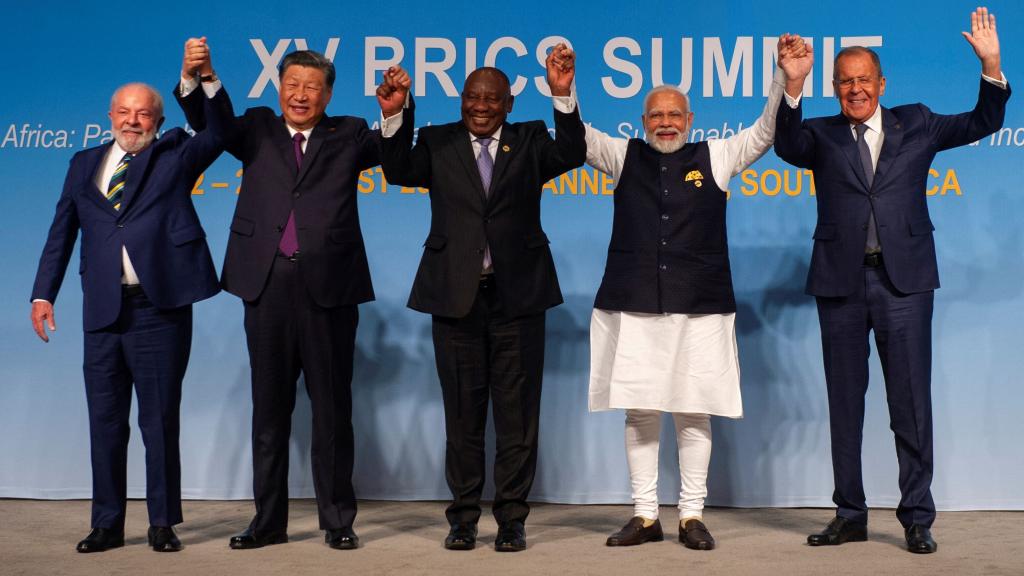

For some, the expansion of BRICS (the trading bloc of Brazil/Russia/India/China/South Africa) is an historic step towards independence and nonalignment. Brazilian President Lula da Silva went so far as to state that the BRICS would be “the driving force of the new international order.”10

But the intent to fully integrate with transnational capitalism was evident from the Johannesburg II Declaration, which marked the culmination of the fifteenth BRICS summit, in August 2023. In it, the BRICS reaffirmed their support for a “rules-based multilateral trading system with the World Trade Organization at its core … a market-oriented agricultural trading system … an adequately resourced International Monetary Fund … [and that] multilateral financial institutions and international organization play a constructive role building global consensus on economic policies.”11

As Patrick Bond points out, “Instead of overturning the high table of Western economic power, the bloc is intent on stabilizing and relegitimizing that ‘rules-based order.’”12

When the BRICS declare that the WTO is at the core of a global trading system, they are supporting a structure that elevates the rights of TNCs over the rights of states. This system privileges the power of transnational capitalists over state elites, because WTO trade courts are built to uphold the right of TNCs to sue governments over unfairly limiting profits or market access. While some court decisions have gone against the United States and Europe, a substantial majority have punished countries in the Global South.

These dispute settlements courts are considered a core WTO activity. They have been used to overrule environmental and labor standards and policies that subsidize national corporations, in effect weakening the power of the state where progressive national elements have influence while strengthening the power of TNCs where Southern social democrats have little or no power.

In a major study of investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) procedures, Shawn Nichols wrote, “the struggle around ISDS represents a global project led by an increasingly dominant transnational capital class [that] has generated substantial opposition in recent years from environmental, labor, and other public interest groups.”13

WTO trade courts have become a template for using ISDS mechanisms by individual countries. Massive volumes of transnational capital are channeled through the Netherlands because it uses such procedures in its bilateral investment agreements with many countries. In 2017, the Netherlands ranked number one in held stock of foreign direct investments abroad with $5.8 trillion, compared to $5.6 for the United States (third came the combined totals for China and Hong Kong at $3.1 trillion).14

The Netherlands’ number-one ranking is stark evidence of how the TCC operates on a global, rather than national, scale. Perhaps the best example is the defense industry, the most “national” of all industries and financed through tax dollars. Nevertheless, six of the 10 largest arms companies maintain legal structures in the Netherlands, and the biggest with almost half of annual defense spending have financial operations.15

The irony of the BRICS supporting the WTO as a “core” of the international system is that the United States has undermined the trade court by blocking new appointments, thereby disrupting its ability to function. Problems began when the WTO ruled against the Trump White House imposing tariffs on Chinese steel and aluminum.

The United States appealed the case, but now there is no Appellate Body because there are no judges. Consequently, the judgement remains in limbo.

On a broader scale the Trump administration, as well as that of Biden, decided that the United States was in a stronger position when negotiating with countries one-on-one, rather than using a court of seven transnational judges.16 Trade panels do continue to function, but 65% of all cases are followed by appeals, which now have nowhere to go.

Why then would BRICS state elites want to re-energize the WTO when that institution was the main target of the anti-globalization movement, and when the trade court is used most often against the Global South?

On the surface, it appears that BRICS constitutes an anti-U.S. bloc. But on a deeper level its members are fighting to defend institutional transnational authority, particularly as their own TNCs grow stronger and desire the power to force open markets and sue governments. And they don’t stand alone.

The Council on Foreign Relations, the most important think-tank linked to U.S. grand strategy, accused the United States of “holding the murder weapon” that killed the WTO.17 This reflects differences between U.S. state and economic elites during a period of upheaval and crisis. Corporate leaders prefer defending globalization, open borders and unrestricted capital flows, while state elites concerned with political instability pursue a partial retreat from globalization and the strengthening of state-centric control.

Between 2016 and September 2023, the Global North brought 30 cases against countries in the Global South, while the South initiated only 11 cases against the North. Additionally, there were 20 cases between countries of the Global South. The United States used the WTO court more than any other country, bringing 29 cases, while China brought nine and India, eight.18

The fact that U.S. corporations used the WTO more than any other is why transnational elites accused the U.S. government of “murdering” the trade court. Moreover, the high number of cases instigated between economic interests in the Global South reveals the lack of any cohesive anti-Western bloc, but rather typical inter-capitalist competition at the expense of the working class and poor.

The Johannesburg II Declaration was filled of course with rhetoric for a fair, inclusive and equitable world trading system based on sustainable development and inclusive growth. It goes on about protecting human rights, fostering peace and development and fighting corruption. But considering the Russian invasion of Ukraine and human rights violations in India, China and among new members Iran, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Ethiopia and Egypt, the hypocrisy is deafening.

Beyond that hypocrisy there exists a deeper problem for socialists and anti-capitalist activists. This is the promotion of an ideology that rejects the basic antagonism between capital and labor, a type of right-wing social democracy that argues the better capitalism does, the better the working-class benefits — like the old slogan “What’s good for General Motors is what’s good for America.”

There’s the equally problematic belief that a widely shared global capitalism can transition to an ecologically sustainable world.

While BRICS declares its faith in creating “a fair competition market environment” it also commits to “workers’ rights … decent work for all and social justice.”19

But when in the history of capitalism has the system produced decent work and social justice for all? In fact, much of its success is based on the exact opposite.

Can capitalism create a world system which is no longer imperialistic, racist and exploitative? This is the delusional path the BRICS states have set off on — or perhaps, the state and corporate leaders who rule over business and trade know full well the need to create a discourse of equality and justice to maintain a shield of political legitimacy.

China and global capital

The most influential promoter of this ideology is the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Its strategy is put forth in terms of “a common destiny for humanity,” a win-win transnational order of trade and investment, and that “all nations and countries should stick together, share weal and woe, live together in harmony, and engage in mutually beneficial cooperation.”

Achieving this “visionary planning for the future: is not to be done through socialism but globalization, which “has improved the allocation of production factors worldwide, including capital, information, technology, labor and management … it draws nations out of isolation and away from the obsolete model of self-reliance, merging their individual markets into a global one.”20

But the reality is that globalization has resulted in widespread exploitation of the working class and peasants of the Global South, and precarity for workers in the North. Yet the CCP reduces imperialism simply to the “hegemonic thinking of certain countries that seek supremacy,” i.e. the United States.21

Evidently the CCP wants to spread its experience to the rest of the world. Without question, globalization has been a success for China, leading to rapid economic development and a middle class of about 250 million people.

Its model includes Keynesian state-directed investments as well as neoliberal labor and financial policies. But the idea that global capitalism will create a middle-class world of peace and environmental sustainability, or even has the material capacity to do so, is badly misleading.

While acknowledging China’s new middle class, we must recognize that Western capitalism also created a large middle class, although based on imperialism abroad, white supremacy at home and brutal exploitation of labor for many decades. Nevertheless, the room for civil society won by the masses in the American and French revolutions allowed just enough space for organization and struggle.

Advances were made particularly in the “Golden Age” of Keynesianism during the four decades following the Second World War. But neoliberal hegemony and globalization severely weakened those gains, undermining legitimacy and creating the deep political and social instability now rampant in the West.

Deindustrialization, job loss, weaker and smaller unions, precarity and deep cuts to the social contract produced a rejection of globalization. Blaming China’s success for capitalists moving U.S. production abroad is a tactic to divert domestic anger and regain political legitimacy.

For the past 40 years the expansion of the Chinese middle class, compared to the shrinking middle class in the West, made China the winner in global restructuring. Its developmental model relied on opening up to massive amounts of foreign direct investments, adopting Western business practices and technology, becoming the world’s workshop and exporting commodities around the globe.

This was done without old-style imperialist adventures abroad. But it did rely on 300 million rural migrants lacking decent housing, good educational opportunities or sufficient health care to fill the needs of the urban economy with cheap labor.22

It also meant closing tens of thousands of state-owned enterprises, consolidating the rest into powerful transnational corporations and encouraging private capital — resulting in the creation of a billionaire and multi-millionaire class contingent of the TCC. Cheap labor, long hours of work, large profits, state-controlled unions and a weak social safety net were a perfect neoliberal success story.

Part of this transformation was the creation of an entrepreneurial and professional middle class, based in both the private sector and among millions of CCP state functionaries. Furthermore, there was a rise in the living standards of core sectors of the working class. Much of this was achieved through the economic direction of the state and neo-Keynesian social policies, such as massive and repeated infrastructure investments.

But it also included neoliberal financial speculation, such as the largest and fastest real-estate expansion in history. This sector encompassed about 25% of the economy. Much of the construction was done on the backs of migrant labor and carried out by private corporations, creating riches for many of the new bourgeoisie.

The industry was built largely on debt and speculation, much like the U.S. housing crisis that exploded in 2008. Millions of middle-class Chinese bought multiple homes, betting on future resale. This was very similar to middle-class Americans who bought and flipped house after house until the real-estate party imploded.

Real-estate corporations overbuilt, middle-class Chinese over bought, and now this speculative market with millions of empty units and no buyers is causing big problems. Some estimates of empty housing units equal the Chinese population of 1.4 billion.

With the largest real-estate corporations sunk into debt, they were unable to pay back their loans, much of which is held by foreign investors. Among the two biggest real estate corporations, Country Garden had $9.4 billion of offshore debt, and Evergrande Group holds $26.7 billion in offshore debt.23

Starting in 2021 through to October 2022, sixty-six real estate developers defaulted, with two-thirds of their debt held in foreign currency. Thirty-nine of these developers alone owed $117 billion of foreign debt24 — evidence of how deeply transnational capital is involved in China’s property market.

In addition to offshore real-estate debt, $84.2 billion in foreign debt is owed by local governments. This debt is in Local Government Financial Vehicles (LGFVs), used to borrow capital for local infrastructure and public projects, issued as bonds mainly as private equity and commercial bills.25 As yet another example of transnational integration, it reveals why the Chinese economy is vital to the entire financial structure of global capitalism.

Although political elites have been pushing corporations to avoid over-reliance on Chinese supply chains, or even fully decoupling, transnational capitalists show no real inclination to do so. The irony of the situation is that a large part of the problem is situated between the Western TCC and its own state elites, rather than between Western and Southern transnational capitalists.

There has been a constant pushback by corporate lobbies against trade and investment restriction. Between 2019 and 2022, U.S. companies paid out more than $150 billion on Chinese import duties, and over 6,000 have sued the U.S. government for reimbursement.26 On her trip to China, US Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo stated, “I did, myself, personally, talk to over a hundred CEOs of US businesses before going to China, and to say they were desperate for some kind of a dialogue is not an exaggeration.”27

Moreover, coinciding closely with Secretary of Treasury Janet Yellin’s China visit were high-profile trips by Bill Gates, Elon Musk and Tim Cook, with Cook stating that Apple had a “symbiotic” relationship with China.

As the Chinese middle and capitalist classes grew and the state grew rich, Western middle and working classes were moving in the opposite direction. The resulting political and economic tension is the basis for much of the deterioration in the U.S.-China state-to-state relationship. But the transnational economic relationship has been highly successful for the TCC hierarchy, North and South.

While state elites are concerned with political legitimacy, corporate elites are concerned with profits. Most of the time, political and economic contingents of the ruling class work in unison. But in times of crisis, contradictions can erupt over their primary interests.

To understand the China/Western TCC relationship we can examine some basic data. In 2022, the top 100 largest foreign firms in China employed three million people, had revenues of one trillion and accounted for seven per cent of the country’s GDP.

Among the top five firms were Foxconn, Volkswagen, Apple, General Motors, HSBC and the Thai agriculture conglomerate Charoen Pokphand Foods. German automakers sell more cars in China than in all of Western Europe; Apple sells more phones in China than the United States.

In fact, the revenues gathered by U.S. TNCs in China are more than their combined revenues from Japan, Britain and Germany.28 Among the top 100 foreign corporations, the United States had the largest presence with 36, followed by Japan, UK, Germany and France.29

Total FDI through 2021 was $2.282 trillion. And those firms that have diversified from China haven’t retreated back to their Western home, but have gone to Vietnam, Malaysia and other countries in the Global South. So while there has been a small geospatial shift, the result has been to strengthen STCC contingents outside of China.

Table 1. Yearly FDI flows into China 2016–202130

| Year | $US (billions) |

|---|---|

| 2016 | 126.00 |

| 2017 | 131.04 |

| 2018 | 134.97 |

| 2019 | 138.13 |

| 2029 | 144.37 |

| 2021 | 173.50 |

It’s also important to investigate how TCC contingents in China and abroad use the transnational financial system to work to their mutual advantage. The Cayman Islands is the main channel that Chinese TNCs use to raise capital by selling equity to foreign investors. In fact, Chinese shell companies in the Caymans and Bermuda account for 60% of outstanding equity issued through all tax havens, and 70% of foreign funds invested in China.

Such investments get around decoupling in a complex set of maneuvers. Shell companies don’t represent direct ownership in Chinese TNCs; in fact the shell doesn’t even own shares in the operating company. Instead, it will own a unit in China called a wholly foreign-owned enterprise (WFOE), which has contracts with the Chinese corporation, shares in the profits and has a voice in operations.

The WFOE sends its profits back to the tax haven shell in the Cayman Islands, which can then pass them to TCC investors in New York, London or anywhere else in the world. The structure is known as a variable-interest entity and counts as equity by international accounting standards.

Stanford researcher Matteo Maggiori writes, “When you mention who uses tax havens, you think of wealthy individuals and large firms from very developed countries. But the picture has changed substantially over the last 10 or 15 years.”31

These are examples of how closely linked global capitalism has become, and must balance any analysis that privileges state-centric tensions as the sole motivating force of international relations. The Chinese and STCC don’t want to undermine global capitalism; their success is dependent on their integration.

As China’s capital surplus grew from billions into trillions, it began a policy of outward-bound expansion, necessary not only as an outlet for accumulated capital, but also as an outlet for its overcapacity in industrial commodities.

Whose choices?

As previously mentioned, the Chinese are exporting their model of development through their trillion-dollar Belt and Road investments. The policy is wrapped in the rhetoric of “win-win,” and that countries have the right to “freely choose” their social system. This narrative lays the basis for non-alignment.

But is there truly such a thing as a “win-win” scenario under capitalism, a system based on the exploitation of labor and on imperialism?

China is doing business with bourgeois state elites and private corporations, based on capitalist market principles. This is a win for Chinese corporations that need to export excess capital and deal with the overproduction of goods.

It also is a mutual win for state and corporate elites in the Global South who profit from the relationship. In addition, the development of infrastructure increases economic activity and therefore benefits trickle down to workers through jobs, an expanded economy, as well as the creation of a managerial middle class.

Capitalism has always based its legitimacy on such an expansion. But the heart of the entire system is still based on the expropriation of surplus value from labor, and its oppressive apparatus. The growth in China, made possible by its previous socialist base, will not be possible in smaller countries.

The Left should avoid sinking into right-wing social democracy, arguing for the common interests of capital and labor, or that capitalism can lead to a “common destiny for humanity.” If our vision has been reduced to supporting efforts by the STCC to become richer and stronger within global capitalism, our strategy for human liberation has gone seriously off track.

What about the Chinese principle that countries have the right to “freely choose” their social system? Given the historic imposition of Western imperialism, often through violence, the right of people to determine their own social system is absolutely correct. But this isn’t truly what China means.

The CCP is speaking about state-to-state relationships in today’s global system. States dominated by the capitalist ruling class take many forms, including bourgeois-democratic, authoritarian, neo-fascist and reactionary theocratic regimes. China’s all-inclusive rhetoric gives cover for authoritarian and theocratic states of the worst kind.

China doesn’t really mean that “people” have the right to choose, but that states have the right to determine how to organize and use their power. When the police and military violently repress mass movements, as in Iran, Sudan, Egypt, Burma or Belarus, exactly whose “country” is it? The language of “countries” means supporting the state and whoever controls it.

The principle sounds great compared to imperialist history, but whatever happened to “people want revolution” or even, people want democracy?

There may be a certain rationale in state-to-state diplomacy in Chinese policy. Under Chou En-lai and Mao, China upheld independence and self-determination and the right to rebel.

The right of people to organize and overthrow reactionary regimes doesn’t mean supporting the right of imperialists to do so. Upholding independence and opposing foreign invasions are socialist principles. But that is different from the Left respecting the “right to choose” a fascist government.

Conclusion

Much of the Global South sees China as a success story, as indeed it is for many. But can its relatively broad-based success be repeated among developing countries?

Is there economic and environmental room within capitalism to produce a sustainable middle-class global society? Or is that narrative, liberally laced with anti-colonial rhetoric constructed to gain legitimacy, cover oppressive policies and serve to open a path to increased wealth and power for the STTC?

With the historic juncture of traditional imperialism alongside the emergence of a transnational capitalist class based in the North and South, we have a complex mix of nationalist and transnational rhetoric and conflict.

Globalization is a re-division of the world through the integration and mixing of national capital, rather than the re-division of colonial territory, or the establishment of a strategic space of independence and non-alignment. Multi-polarity is basically a fight for equality among capitalists of different types and ideologies. It may de-center the old U.S.-dominated system, but in that process we must distinguish what is historically progressive and what isn’t.

Does the drive for multi-polarity enhance the ability of states to develop in a way that benefits all classes or a drive for equality among capitalists and the freedom to establish authoritarian regimes as accepted and respected alternatives to U.S. imperialism? For the Left, working-class internationalism seems more appropriate than multi-polarity as our guide.

In the American Revolution independence and self-determination were, from the capitalist viewpoint, all about property rights. Civil society and popular democracy were concessions to the revolutionary masses, the foot soldiers who defeated British colonialism.

Is a democratic civil society the type of concession offered today by Saudi Arabia, Iran, Russia and other authoritarian states? During the post-World War II anti-colonial era, national bourgeoisies were often swept up in patriotic, socialist and democratic rhetoric. Some of that came to fruition, while other countries sank into corruption and the consolidation of capitalist relations.

We are well past the non-aligned promise of Bandung. Southern capitalists have matured, their leading elements are contingents of the TCC, and multi-polarity is based on this new stage of development.

- 1

PPP is the exchange rate at which one nation’s currency would be converted into another to purchase the same amount of a large group of products. The G7 consists of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States.

- 2

N. Spiro, “Why China’s dominance puts Brics expansion plans and very existence in jeopardy,” South China Morning Post, 17 August 2023, available at https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3231367/why-chinas-dominance-puts-brics-expansion-plans-and-very-existence-jeopardy.

- 3

Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute (SWFI), “Top 100 Largest Financial Holding Company Ranking by Total Assets,” available at https://www.swfinstitute.org/fund-rankings/financial-holding-company.

- 4

SWFI, “Top 100 Largest Company Rankings by Total Assets.”

- 5

M. Shaban, “The breakdown of the wealthy across the globe,” Altrata, 30 May 2023, available at https://altrata.com/articles/a-breakdown-of-the-wealthy-across-the-globe.

- 6

S. Vitali, J. B. Glattfelder and S. Battiston, “The network of global corporate control,” PLOS ONE, 26 October 2011, available at https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0025995.

- 7

SWFI, “Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA) increased its ownership in Mercedes-Benz Group,” Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute, 24 January 2023, available at https://www.swfinstitute.org/news/95535/qatar-investment-authority-expands-stake-in-credit-suisse.

- 8

SWFI, “Norway Taps Norges Bank for Billions,” 12 May 2023, available at https://www.swfinstitute.org/news/97293/norway-taps-norges-bank-for-billions.

- 9

S. M. Rosenthal and T. Burke, “Who owns US stock? Foreigners and rich Americans,” Tax Policy Institute, 20 October 2020, available at https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxvox/who-owns-us-stock-foreigners-and-rich-americans.

- 10

J. Nyabiage, “Global impact: expansion to ‘inject new vitality’ into Brics as nations seek to counterbalance Western dominance,” South China Morning Post, 4 September 2023, available at https://www.scmp.com/economy/global-economy/article/3233290/global-impact-expansion-inject-new-vitality-brics-nations-seek-counterbalance-western.

- 11

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, “Johannesburg II Declaration. BRICS and Africa: partnership for mutually accelerated growth, sustainable development and inclusive multilateralism, Sandton, Gauteng, South Africa, 23 August 2023,” 24 August 2023, available at https://mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/news/1901504/.

- 12

P. Bond, “BRICS+ emerge from Johannesburg, humbled as sub-(not anti- or inter-) imperialists,” Z Network, 29 August 2023, available at https://znetwork.org/znetarticle/brics-emerge-from-johannesburg-humbled-as-sub-not-anti-or-inter-imperialists/.

- 13

S. Nichols, “Transnational Capital and the Transformation of the State: Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) in the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP),” Critical Sociology 45, no. 1: 137–157.

- 14

CIA World Factbook, “List of countries by FDI abroad,” Wikipedia, available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_FDI_abroad.

- 15

M. Broek, “Tax evasion and weapon production: nailbox arms companies in the Netherlands,” Amsterdam, TNI, 2 June 2016, available at https://www.tni.org/en/publication/tax-evasion-and-weapon-production.

- 16

Monthly Review, “Notes from the Editors,” available at https://monthlyreview.org/2023/10/01/mr-075-06-2023-09_0/.

- 17

Monthly Review, “Notes from the Editors.

- 18

World Trade Organization, “Chronological list of disputes cases,” available at https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/dispu_status_e.htm.

- 19

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, “Johannesburg II Declaration.”

- 20

The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, ‘A Global Community of Shared Future: China’s Proposals and Actions’, 26 August 2023, http://ws.china-embassy.gov.cn/eng/xwdt/202309/t20230927_11151195.htm.

- 21

The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, “A Global Community of Shared Future: China’s Proposals and Actions.”

- 22

China Labour Bulletin, “Migrant workers and their children,” 6 September 2023, available at https://clb.org.hk/en/content/migrant-workers-and-their-children.

- 23

C. Bray and Y. Ao, “China property crackdown: why surprise victim Country Garden could be worse than Evergrande for the economy,” South China Morning Post, 2 September 2023, available at https://www.scmp.com/business/china-business/article/3233079/china-property-crackdown-why-surprise-victim-country-garden-could-be-worse-evergrande-economy.

- 24

I. Ouyang, “China property: junk-bond party has begun as December rush delivers windfall, leaves Nomura, Goldman at risk of missing the boat,” South China Morning Post, 17 December 2022, available at https://www.scmp.com/business/banking-finance/article/3203601/china-property-junk-bond-party-has-begun-december-rush-delivers-windfall-leaves-nomura-goldman-risk.

- 25

I. Ouyang, “China’s weaker LGFVs face default risks as property crisis hurts local authorities’ re

- 26

K. Razdan, “US importers demand refund of Trump-era tariffs on Chinese goods worth billions of dollars,” South China Morning Post, 28 February 2023

- 27

J. Coleman, “Commerce Secretary Raimondo: US businesses are ‘desperate for some kind of dialogue’ with China,” CNBC Mad Money, 5 September 2023, available at https://www.cnbc.com/2023/09/05/secretary-raimondo-us-businesses-are-desperate-for-dialogue-with-china.html.

- 28

A. Swanson, “The contentious U.S.-China relationship, by the numbers,” The New York Times, 7 July 2023, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/07/business/economy/us-china-relationship-facts.html.

- 29

E. Mak, “Foxconn, Volkswagen and Apple top the list of largest foreign firms operation in China: Hurun,” South China Morning Post, 21 December 2022, available at https://www.scmp.com/tech/big-tech/article/3234474/apple-defends-iphone-12-radiation-level-after-france-ordered-national-sales-ban?campaign=3234474&module=perpetual_scroll_1_AI&pgtype=article.

- 30

K. Lo, ‘“Small-scale dip’? China downplays FDI inflow decline that may be having a big impact on confidence,” South China Morning Post, 25 July 2023, available at https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3228745/small-scale-dip-china-downplays-fdi-inflow-decline-may-be-having-big-impact-confidence.

- 31

P. Coy, “Chinese companies are doing risky business in the Caribbean,” The New York Times, 8 March 2023, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/08/opinion/china-tax-haven-shell-companies.html.