Artists visit Austertana - the village where interests of mining, ecology and reindeer herding clash

By Hannah Thule

BARENTS OBSERVER

August 15, 2024

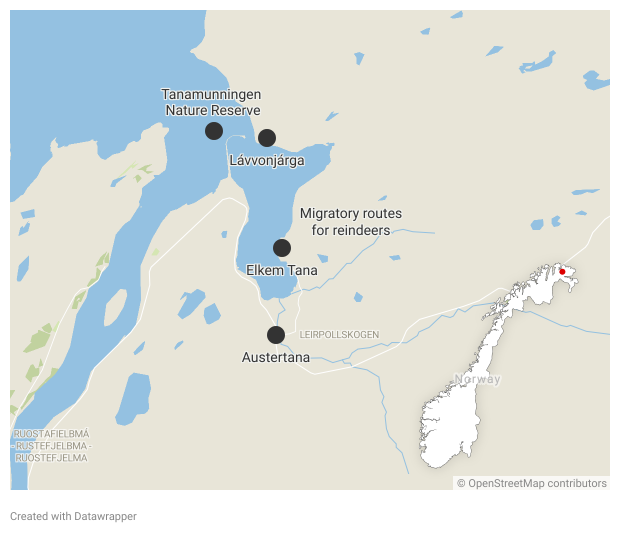

In Austertana the quartzite quarry Elkem Tana plays a significant role, providing jobs to the local community. Over the years, the company's ambitious expansion plans have both caused conflict with the local Sámi reindeer herding district and raised concerns about the impact on the Tanamunningen Nature Reserve’s ecosystem. These issues are explored in an art project by two Danish artists who have visited the village on several occasions for the past few years.

Austertana is located in northeastern Norway, close to the Russian and Finnish borders. The area is part of Sápmi - the cultural region of Sámi People where reindeer herding is a central.

The small northeastern Norwegian village of Austertana, located in the Tana municipality, is home to Elkem Tana - one of the world’s largest open-pit quartzite mines.

Every year, 850,000 million tonnes of quartzite is transported from the mine by cargo ships to smelters both in Norway and around the world.

A few years ago, the mine captured the interest of Danish media artist Nanna Elvin Hansen.

In her pursuit to trace the origins of the materials used in her own sound and media devices, as well as in satellite imagery employed by extractive industries to identify underground resources, Elvin Hansen discovered that it all begins with quartzite.

Silicon carbide, derived from quartzite, is used in a variety of products, including the optical lenses for satellites and components in electronics.

A faint hum from the machines and trucks at the mine can be heard across the fjord. Photo: Hannah Thulé

“I followed the supply chain, which led me to Austerana and the mine of Elkem”, the artist explains.

Together with sound artist Eliza Bożek, Elvin Hansen visited Austertana multiple times to photograph, film, and record sound at the mine and its surrounding area.

Through these recordings, the impact of the mine on the local community and environment is shown, while also raising global questions such as those of consumption, climate change, and the displacement of both humans and non-humans.

Hear the people

In addition to listening to the landscape, it was important to listen to the locals living here, the artist duo explains.

“The project in itself is about industrial extractivism and it was important that the art in itself wouldn’t be extractive. We are guests in the landscape,” Elvin Hansen says.

“I followed the supply chain, which led me to Austerana and the mine of Elkem”, the artist explains.

Together with sound artist Eliza Bożek, Elvin Hansen visited Austertana multiple times to photograph, film, and record sound at the mine and its surrounding area.

Through these recordings, the impact of the mine on the local community and environment is shown, while also raising global questions such as those of consumption, climate change, and the displacement of both humans and non-humans.

Hear the people

In addition to listening to the landscape, it was important to listen to the locals living here, the artist duo explains.

“The project in itself is about industrial extractivism and it was important that the art in itself wouldn’t be extractive. We are guests in the landscape,” Elvin Hansen says.

The quarry is located near the peak of a mountain known as Giemaš to the Sámi people. Photo: Hannah Thulé

The art project culminated in multichannel video and sound installation presented in Copenhagen in 2023 as well as a documentary film and field recording vinyl.

The underwater recordings of the soundscape capture, among other things, the presence of animal life and the disruptive, loud engine noises of the cargo ships.

The artists also recorded sounds around the village and at the mine.

“The mine is very present in the soundscape of the whole area,” Bożek concludes.

The art project culminated in multichannel video and sound installation presented in Copenhagen in 2023 as well as a documentary film and field recording vinyl.

The underwater recordings of the soundscape capture, among other things, the presence of animal life and the disruptive, loud engine noises of the cargo ships.

The artists also recorded sounds around the village and at the mine.

“The mine is very present in the soundscape of the whole area,” Bożek concludes.

It felt important for artists Eliza Bożek (left) and Nanna Hansen Elvin to return to Austertana and show the film to the locals. Photo: Hannah Thulé

In the film, the theme of industrial extractivism and its impact on nature and its inhabitants is explored. This is partially conveyed through local voices recounting their experiences with the Elkem mine. Ultimately, the viewer is left pondering the question, “How much is a mountain worth?”

Elvin Hansen emphasises that it was crucial to avoid placing blame on the people of Austertana.

“All people who consume products developed from quartzite are equally accountable. No one can be innocent, at least very few,” the artist adds.

Contested expansion

In the small town of Austertana with a population of 175, Elkem is a big player.

When the mine was established in 1973, the farming village gradually transformed into a mining community. Today, only three farms remain.

Elkem has operated the mine since 1983 and provides today around 50 local jobs. In 2011, Chinese state-owned enterprise China National BlueStar became the major shareholder.

For many years, the Sámi reindeer herders of District 7, also known as Rákkonjárga, and Elkem coexisted peacefully. The quartzite quarry facing the fjord did not interfere with the reindeer herding activities taking place on the other side of the mountain.

However, the company’s expansion plans have sparked conflict both with and among local residents.

In the film, the theme of industrial extractivism and its impact on nature and its inhabitants is explored. This is partially conveyed through local voices recounting their experiences with the Elkem mine. Ultimately, the viewer is left pondering the question, “How much is a mountain worth?”

Elvin Hansen emphasises that it was crucial to avoid placing blame on the people of Austertana.

“All people who consume products developed from quartzite are equally accountable. No one can be innocent, at least very few,” the artist adds.

Contested expansion

In the small town of Austertana with a population of 175, Elkem is a big player.

When the mine was established in 1973, the farming village gradually transformed into a mining community. Today, only three farms remain.

Elkem has operated the mine since 1983 and provides today around 50 local jobs. In 2011, Chinese state-owned enterprise China National BlueStar became the major shareholder.

For many years, the Sámi reindeer herders of District 7, also known as Rákkonjárga, and Elkem coexisted peacefully. The quartzite quarry facing the fjord did not interfere with the reindeer herding activities taking place on the other side of the mountain.

However, the company’s expansion plans have sparked conflict both with and among local residents.

The sign reads that Elkem Tana is raw material supplier for the green transition. Quartzite is among other things needed for the production of electrical cars and wind turbines. Photo: Hannah Thulé

On one hand, the mine provides jobs to the local community and quartzite is crucial for the green transition, being essential for the production of electric cars and renewable energy systems such as wind power and solar panels.

On the other hand, the mine is situated on Sámi land, and any expansion impacts reindeer herding practices, including the migratory routes and grazing patterns of the reindeer.

In 2019, the mining company applied to expand its operational area by nearly five square kilometers, down from a previous request for an expansion twice that size.

The Director at the time, Rune Martinussen, told iFinnmark.no that if Elkem is not permitted to expand its area, the alternative would be downsizing and closure by 2025.

The expansions were for obvious reasons to be discussed with the reindeer herding district.

On one hand, the mine provides jobs to the local community and quartzite is crucial for the green transition, being essential for the production of electric cars and renewable energy systems such as wind power and solar panels.

On the other hand, the mine is situated on Sámi land, and any expansion impacts reindeer herding practices, including the migratory routes and grazing patterns of the reindeer.

In 2019, the mining company applied to expand its operational area by nearly five square kilometers, down from a previous request for an expansion twice that size.

The Director at the time, Rune Martinussen, told iFinnmark.no that if Elkem is not permitted to expand its area, the alternative would be downsizing and closure by 2025.

The expansions were for obvious reasons to be discussed with the reindeer herding district.

Agreement reached

After five years of negotiations, the mining company and Rákkonjárga reached an agreement in December 2023.

Magne Andersen, Leader of Rákkonjárga, explains that the reindeer herding district could not agree to the area requested by Elkem because it included crucial migratory tracks used by the reindeer.

In the end, an area spanning 600 meters across the mountain was agreed upon.

Additionally, Elkem has promised to suspend mining activities in the new area from the end of July to the end of September, to allow the reindeer the peace they need while migrating.

The agreement also includes a compensation fee paid to Rákkonjárga, although the exact amount remains confidential.

After five years of negotiations, the mining company and Rákkonjárga reached an agreement in December 2023.

Magne Andersen, Leader of Rákkonjárga, explains that the reindeer herding district could not agree to the area requested by Elkem because it included crucial migratory tracks used by the reindeer.

In the end, an area spanning 600 meters across the mountain was agreed upon.

Additionally, Elkem has promised to suspend mining activities in the new area from the end of July to the end of September, to allow the reindeer the peace they need while migrating.

The agreement also includes a compensation fee paid to Rákkonjárga, although the exact amount remains confidential.

Magne Andersen, Leader of reindeer herding district 7, has worked with reindeers all his life. Photo: Hannah Thulé

Magne Andersen describes the past years of negotiation as exhausting.

“Of course there were nights when it was impossible to sleep”.

Andersen says that the Sámi experienced discrimination during the talks with Elkem.

“The first Director was “one of those” [who discriminates] and we refused to negotiate with him. Then Elkem changed Director to a Sámi who comes from a family where reindeer herding is practised, that was when the negotiations could continue,” Andersen explains.

He adds that the Supreme Court ruling in the Fosen case in 2021, which determined that the Norwegian state’s decision to construct wind turbines at Fosen violated the Sámi people’s rights to practice reindeer herding, played a significant role in the negotiations with Elkem.

“They realised it isn’t possible to run over us.”

The reindeer herders also experienced pressure from the local residents.

“They said that we don’t care about their jobs. But what about our jobs, without the land we can’t practise reindeer herding. Everybody was on their side, all the politicians as well.”

Magne Andersen describes the past years of negotiation as exhausting.

“Of course there were nights when it was impossible to sleep”.

Andersen says that the Sámi experienced discrimination during the talks with Elkem.

“The first Director was “one of those” [who discriminates] and we refused to negotiate with him. Then Elkem changed Director to a Sámi who comes from a family where reindeer herding is practised, that was when the negotiations could continue,” Andersen explains.

He adds that the Supreme Court ruling in the Fosen case in 2021, which determined that the Norwegian state’s decision to construct wind turbines at Fosen violated the Sámi people’s rights to practice reindeer herding, played a significant role in the negotiations with Elkem.

“They realised it isn’t possible to run over us.”

The reindeer herders also experienced pressure from the local residents.

“They said that we don’t care about their jobs. But what about our jobs, without the land we can’t practise reindeer herding. Everybody was on their side, all the politicians as well.”

Throughout the year, reindeer migrate between pastures, staying in different areas depending on the season. The migratory routes close to the mine were at risk of being compromised due to the company’s ambitious expansion plans. Photo: Hannah Thulé

Andersen is quite certain the fight isn’t over.

Elkem is not permitted to seek permission for another expansion for seven years. However, the reindeer herder believes they will attempt to do so once that period has passed.

“As a Sámi you have to keep on fighting.”

Wind power

The mine isn’t the only headache for the reindeer herders.

“We did the mistake giving permission for wind park projects in two areas many years ago,” Andersen says.

The areas are Rakkucearru in Berlevåg and Hamnefjellet in Båtsfjord.

Rakkucearru consists of three phases: I, II, and III. The first two have been built, and the third is to be constructed.

Hamnefjellet consists of two phases: the first has been built, and the second is to be constructed.

Rakkucearru III has been moved northward from its originally planned location out of consideration for reindeer herding. After doing this, they are now applying to build in the area they moved away from, Andersen tells.

Andersen is quite certain the fight isn’t over.

Elkem is not permitted to seek permission for another expansion for seven years. However, the reindeer herder believes they will attempt to do so once that period has passed.

“As a Sámi you have to keep on fighting.”

Wind power

The mine isn’t the only headache for the reindeer herders.

“We did the mistake giving permission for wind park projects in two areas many years ago,” Andersen says.

The areas are Rakkucearru in Berlevåg and Hamnefjellet in Båtsfjord.

Rakkucearru consists of three phases: I, II, and III. The first two have been built, and the third is to be constructed.

Hamnefjellet consists of two phases: the first has been built, and the second is to be constructed.

Rakkucearru III has been moved northward from its originally planned location out of consideration for reindeer herding. After doing this, they are now applying to build in the area they moved away from, Andersen tells.

Magne Andersen shows the migratory tracks of the reindeer. Photo: Hannah Thulé

At that time when Rákkonjárga said yes to the projects, it was claimed that wind turbines do not disturb the reindeer, something current research rejects.

“On clear days, when the reindeer can see the turbine blades, they avoid coming closer than 12-13 kilometers to the turbines.”

“They take small portions of Sámi land here and there, suggesting it doesn’t matter if we lose a little land. However, these small losses accumulate to a significant amount over time,” Andersen concludes.

Tana Nature Reserve

Another area of concern related to the mine is the transportation of the quartzite.

To reach the quarry, the cargo ships must pass through the Tanamunningen Nature Reserve, where they are currently restricted to carrying loads of no more than 6,000 tons.

In 2012, Elkem expressed a desire to use 10,000-ton ships, which would have required the channel to be deepened and widened.

The nature reserve is characterised by a diverse ecosystem that includes wetlands, mudflats, and sandbanks. These habitats are critical for various bird species, particularly as a stopover and breeding ground for migratory birds.

At that time when Rákkonjárga said yes to the projects, it was claimed that wind turbines do not disturb the reindeer, something current research rejects.

“On clear days, when the reindeer can see the turbine blades, they avoid coming closer than 12-13 kilometers to the turbines.”

“They take small portions of Sámi land here and there, suggesting it doesn’t matter if we lose a little land. However, these small losses accumulate to a significant amount over time,” Andersen concludes.

Tana Nature Reserve

Another area of concern related to the mine is the transportation of the quartzite.

To reach the quarry, the cargo ships must pass through the Tanamunningen Nature Reserve, where they are currently restricted to carrying loads of no more than 6,000 tons.

In 2012, Elkem expressed a desire to use 10,000-ton ships, which would have required the channel to be deepened and widened.

The nature reserve is characterised by a diverse ecosystem that includes wetlands, mudflats, and sandbanks. These habitats are critical for various bird species, particularly as a stopover and breeding ground for migratory birds.

The Tanamunningen Nature Reserve is critical to various bird species that feed on sandeel. Dredging the passage would destroy the sandeel’s habitat. Photo: Hannah Thulé

Øystein Hauge, a local resident of Austertana and environmentalist, explains that the sandeel, which buries itself in the sand in shallow water, is a key species and crucial food source for birds. Dredging would compromise it’s habitat.

Due to the ecological importance of the nature reserve, the plans faced protests, and ultimately, the Norwegian Kystverket decided to shelve the investigation in 2022.

Hauge says that interest in dredging the passage still persists at the political level.

He also criticises the environmental impact assessment published in 2022, arguing that the company never explored alternative solutions.

The option of transporting the quartzite with smaller vessels out of the fjord to a pickup point and then transferring it to larger ships has never been explored, Hauge adds.

Øystein Hauge, a local resident of Austertana and environmentalist, explains that the sandeel, which buries itself in the sand in shallow water, is a key species and crucial food source for birds. Dredging would compromise it’s habitat.

Due to the ecological importance of the nature reserve, the plans faced protests, and ultimately, the Norwegian Kystverket decided to shelve the investigation in 2022.

Hauge says that interest in dredging the passage still persists at the political level.

He also criticises the environmental impact assessment published in 2022, arguing that the company never explored alternative solutions.

The option of transporting the quartzite with smaller vessels out of the fjord to a pickup point and then transferring it to larger ships has never been explored, Hauge adds.

Øystein Hauge, a local resident of Austertana and environmentalist, says that interest in dredging the passage still persists. Photo: Hannah Thulé

“It is evidently more convenient for Elkem to have the Norwegian state cover the cost of dredging the passage through the Tanamunningen Nature Reserve.”

Hauge also questions if the dredging would be a one time thing.

“With 80,000 cubic meters of water flowing in and out of the fjord with the tide, the movement of sand is an expected factor. However, this aspect was not investigated in 2022.”

Back to the artists

Eliza Bożek and Nanna Elvin Hansen returned to Austertana in the beginning of August.

For the duo it was important to come back and share the documentary with the local community.

“It is evidently more convenient for Elkem to have the Norwegian state cover the cost of dredging the passage through the Tanamunningen Nature Reserve.”

Hauge also questions if the dredging would be a one time thing.

“With 80,000 cubic meters of water flowing in and out of the fjord with the tide, the movement of sand is an expected factor. However, this aspect was not investigated in 2022.”

Back to the artists

Eliza Bożek and Nanna Elvin Hansen returned to Austertana in the beginning of August.

For the duo it was important to come back and share the documentary with the local community.

Danish artists Nanna Elvin Hansen and Eliza Bożek stayed for some time in Lávvonjárga, a spot accessible by boat in summer. There the duo recorded sounds underwater and streamed live radio. Cargo ships from the quarry pass by, not far from the beach. Photo: Hannah Thulé

“The generosity of the people was so impactful. We received so much when we were here. It was good to come back and give something back,” Eliza says.

The locals are also the key audience for the film, talking about the issues here evokes more emotions than showing it to the audience in Copenhagen, Elvin Hansen adds.

Both artists express that the small village of Austertana has had a profound impact on them.

In addition to the generosity of the locals, Elvin Hansen explains that realising how deeply connected and knowledgeable they are about the surrounding landscape has led her to reflect on how people living in cities, including herself, might cultivate a similar connection and care for their environment.

“The generosity of the people was so impactful. We received so much when we were here. It was good to come back and give something back,” Eliza says.

The locals are also the key audience for the film, talking about the issues here evokes more emotions than showing it to the audience in Copenhagen, Elvin Hansen adds.

Both artists express that the small village of Austertana has had a profound impact on them.

In addition to the generosity of the locals, Elvin Hansen explains that realising how deeply connected and knowledgeable they are about the surrounding landscape has led her to reflect on how people living in cities, including herself, might cultivate a similar connection and care for their environment.

The tops of Giemaš. Photo: Hannah Thulé