Audrey Tan and Walter Sim

Updated

Aug 19, 2024

FUKUSHIMA – Tanks full of seafood are not what one usually expects to find at a nuclear power station.

Yet, The Straits Times discovered quite a spread at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station during a visit there in June.

Flounder, abalone and seaweed – all delicacies of north-eastern Japan – were being reared on site, though they were not bound for the dinner table.

Plant operator Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco) has far greater aspirations for them.

The cameras in the flounder tanks provide a clue to their existence: By live-streaming the activities of these fishes 24/7, Tepco wants to show the world that water being discharged after treatment from the nuclear plant – the site of the 2011 nuclear disaster – is safe and has no negative impact on life underwater.

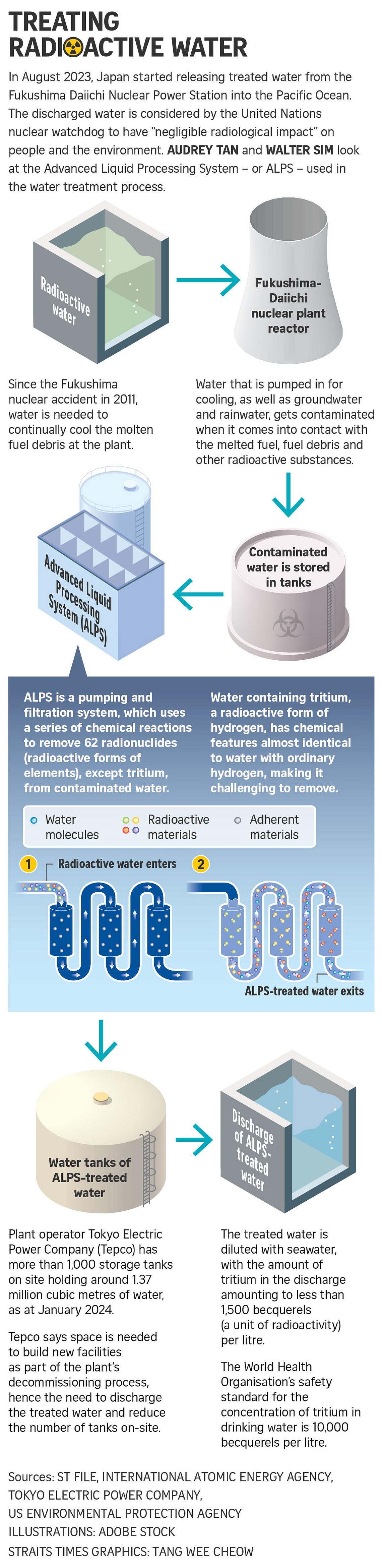

Sources of contaminated water include seawater used to cool the remaining nuclear fuel, as well as groundwater and rainwater that seep into the damaged reactors.

Within the marine life breeding facility, tanks are colour-coded.

Seafood in yellow tanks is reared in water that has been processed through the Advanced Liquid Processing System (ALPS) that removes radioactive material, and then diluted with seawater. This same mixture is what the plant discharges into the ocean.

Blue tanks contain fish reared in regular seawater.

Mr Kazuo Yamanaka, who oversees the marine organisms rearing test laboratory at Fukushima Daiichi, told us during our visit: “When there were discussions over the release of the ALPS-treated water, we heard concerns from fishermen who were worried about the damage to their trades through harmful rumours.”

The fishing industry in Fukushima had expressed worries that consumers would be afraid of consuming seafood in the area.

“We spoke to locals and stakeholders in the fishing industry, who said they wanted to see flounder and abalone moving and growing healthily in seawater that has been mixed with ALPS-treated water,” Mr Yamanaka added.

Tepco started rearing the marine life in September 2022, about a year before the first discharge of ALPS-treated water into the Pacific Ocean began on Aug 24, 2023.

Japanese media reported that outgoing Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is set to visit the crippled nuclear plant on Aug 24, to mark the first anniversary of the first treated water discharge.

Japan’s Tepco to start fourth release of treated waste water from Fukushima plant in late February

Radioactivity concentrations in the tissues of marine organisms are also monitored regularly, with the results published on Tepco’s website.

Eight batches of treated water have been released so far, with the most recent starting on Aug 7 and expected to end on Aug 25.

With the completion of the discharge of the seventh batch on July 16, about 55,000 cubic metres of water – enough to fill about 22 Olympic-size pools – has been discharged into the ocean so far.

Japan plans to continue releasing the diluted ALPS-treated water from Fukushima Daiichi over the next decades in a series of batches.

The United Nations’ nuclear watchdog, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), has said the release meets international safety standards and would have “negligible radiological impact on people and the environment”.

In Singapore, the Singapore Food Agency (SFA) ensures food safety through a surveillance and monitoring regime, while the National Environment Agency (NEA) keeps watch over ambient radiation levels in Singapore via a network of 40 stations, and through regular sampling and laboratory analysis of Singapore’s waters.

In a joint response, the agencies said that no radioactive contaminants have been detected in food imports from Japan since 2013. Such contaminants had been detected in Japanese food imports in 2011 and 2012. Food imports from the East Asian country into Singapore have made up less than 1.5 per cent of total food imports over the past decade, with less than 0.01 per cent of food coming from Fukushima prefecture in 2022, they noted.

As for ambient radioactivity levels, these have remained within natural background levels, the agencies said

Making space

The Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station sits on a sprawling compound measuring 3.5 sq km, about 10 times the size of the Singapore Sports Hub.

More than a decade since the plant was hit by a 9.0-magnitude earthquake and tsunami that resulted in the 2011 nuclear disaster, the plant still bears visible reminders of the incident.

The four buildings that house the nuclear reactors are still on site, and highly radioactive fuel debris still remains in two of them. Seawater is continually needed to cool the molten fuel.

Any water that comes into contact with the radioactive material – including the seawater used for cooling, as well as groundwater and rainwater that seep into the damaged reactors – becomes contaminated.

At Fukushima Daiichi, this contaminated water is treated via ALPS to remove most of the radioactive elements before it is stored in tanks.

Looking over the compound from a meeting room where we were briefed on safety protocols, we could see that most of the campus was covered with huge vats of blue, white and grey, which are used for storing the treated water.

As at January, there were more than 1,000 tanks on site, storing about 1.37 million cubic metres of water – equivalent to 548 Olympic-size swimming pools.

But as works to decommission – or to safely close and dismantle – the plant progressed, space was needed to construct new facilities.

Mr Junichi Matsumoto, Tepco’s chief officer for ALPS-treated water management, said: “Storing this treated water on site was always a stopgap measure – there is space for only so many tanks. That is why the Japanese government, after thorough consultation with the International Atomic Energy Agency, made the decision to discharge it.”

Japan first announced plans to discharge the treated water into the Pacific Ocean in 2021.

The Japanese authorities requested technical assistance from the IAEA to monitor and review those plans.

In 2023, the IAEA’s safety review concluded that Japan’s plans to release treated water stored at Fukushima Daiichi into the sea were consistent with its safety standards.

The treatment process

ALPS removes most of the radioactive elements from contaminated water via a series of chemical reactions.

But tritium – a radioactive form of hydrogen (H) – cannot be removed since water (H2O) containing tritium has chemical features almost identical to water with ordinary hydrogen.

The Fukushima plant is not the only nuclear station to discharge tritiated water – or water that contains tritium.

“Most nuclear power plants around the world routinely and safely release treated water, containing low-level concentrations of tritium and other radionuclides, to the environment as part of normal operations,” the IAEA added.

To allay concerns, Tepco further dilutes the ALPS-treated water with seawater before discharging it into the ocean.

Tritium concentrations in the ALPS-treated water diluted with seawater are less than 1,500 becquerels per litre (Bq/L), a unit of measurement for radioactivity.

The World Health Organisation’s guideline for the limit of tritium in drinking water is 10,000 Bq/L.

Mr Matsumoto said each batch of treated water released into the ocean involves stringent testing.

Workers check the ALPS-treated water for radioactive materials before discharge.

They also collect seawater samples from monitoring points around the power station after the discharge begins.

“Each time, the results have corresponded closely with our pre-discharge simulations, with levels of radioactive materials remaining well within agreed-upon safety standards,” added Mr Matsumoto, who is also corporate officer and general manager of Tepco’s Project Management Office.

The IAEA also independently monitors the tritium concentrations in each batch of treated water discharged by the nuclear power station.

The SFA and NEA told The Straits Times that tritium has not been detected in seafood imports from Japan.

But tritium is not a concern in seafood imports because it emits weak radiation, the agencies said in a joint response.

“The Japanese government has set a concentration limit for tritium at 1,500 Bq/L for the discharge of its treated nuclear wastewater and the international safety limit set by the World Health Organisation and Codex for tritium in food is 10,000 Bq/kg,” said SFA and NEA.

Mr Kazuhiro Shiono, 39, an employee at Marufuto Chokubaiten – a store selling seafood products at the Onahama Port about an hour’s drive from the nuclear plant – told The Straits Times that he was not worried about the discharge of the ALPS-treated water.

“(Tepco) is releasing properly treated water in the ocean, not contaminated water. It is only water that has been properly treated. That is what the government is saying, and I’m absolutely relieved about that,” said Mr Shiono.

“If there were problems with the data, I’d be dead by now... I’ve been eating a lot of fish and giving fish to my own children,” added the father of two.

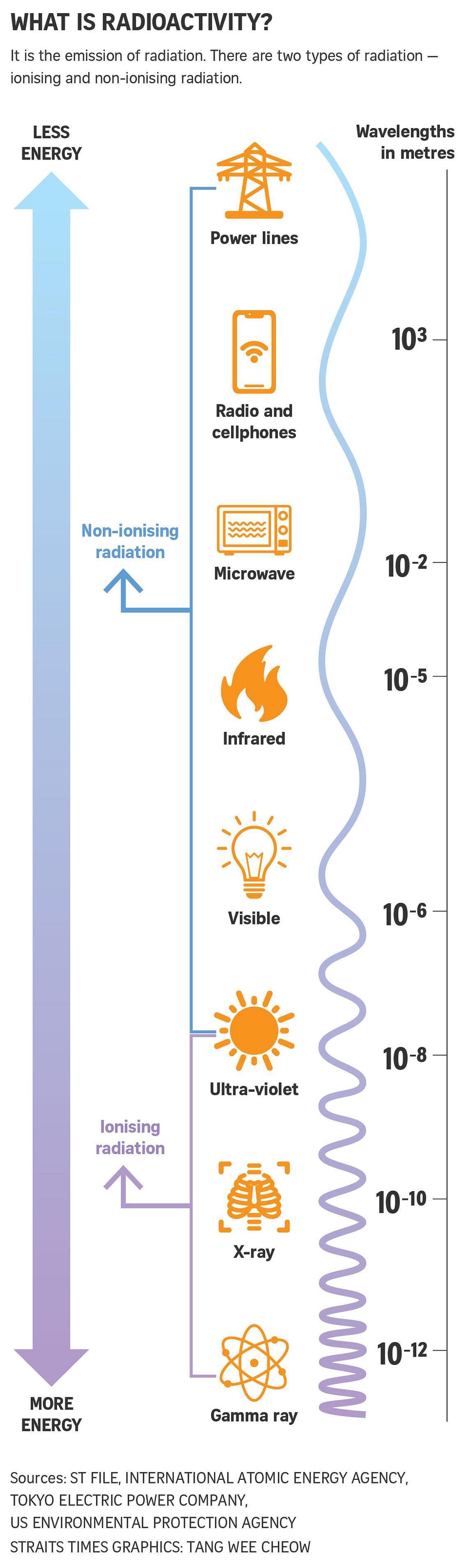

What is radioactivity?

It is the emission of radiation, a form of energy. There are two types of radiation – ionising radiation and non-ionising radiation.

Non-ionising radiation has enough energy to move atoms in a molecule around or cause them to vibrate, but not enough to remove electrons from atoms. Examples of this kind of radiation are radio waves, visible light and microwaves.

Ionising radiation has enough energy to knock electrons out of atoms. In large doses, it poses a health risk in living things as it can damage tissue and DNA in genes.

Japan to consider allowing nuclear plant expansions

ST Explains: What are S-E Asia’s nuclear ambitions and why should S'pore care?

Ionising radiation in the form of alpha particles, beta particles, gamma rays or neutrons is produced by unstable forms of elements, which are the fundamental building blocks of nature.

There are some elements with no stable form that are always radioactive, such as uranium.

Ionising radiation comes from X-ray machines, cosmic particles from outer space and radioactive elements.