‘He was in mystic delirium’: was this hermit mathematician a forgotten genius whose ideas could transform AI – or a lonely madman?

Phil Hoad

Sat 31 August 2024

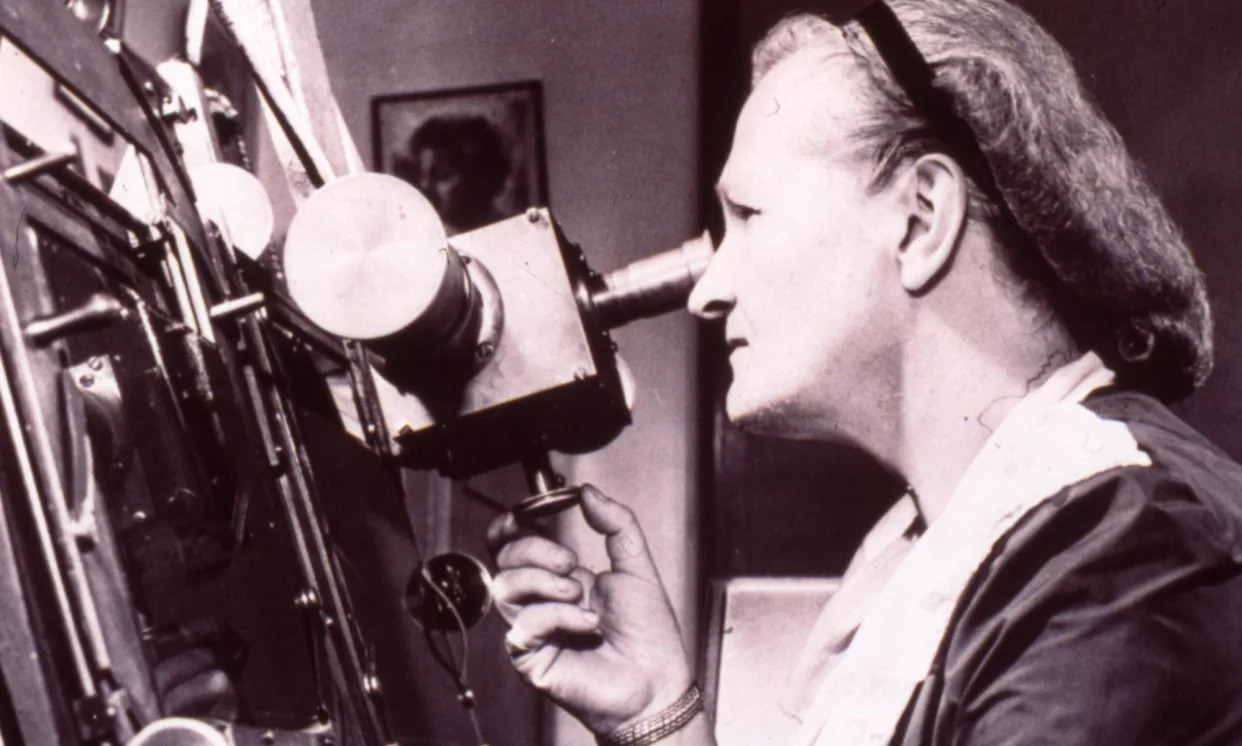

Alexander Grothendieck photographed at his home in Lassarre, France, in 2013.

LONG READ

One day in September 2014, in a hamlet in the French Pyrenean foothills, Jean-Claude, a landscape gardener in his late 50s, was surprised to see his neighbour at the gate. He hadn’t spoken to the 86-year-old in nearly 15 years after a dispute over a climbing rose that Jean-Claude had wanted to prune. The old man lived in total seclusion, tending to his garden in the djellaba he always wore, writing by night, heeding no one. Now, the long-bearded seeker looked troubled.

“Would you do me a favour?” he asked Jean-Claude.

“If I can.”

“Could you buy me a revolver?”

Jean-Claude refused. Then, after watching the hermit – who was deaf and nearly blind – totter erratically about his garden, he telephoned the man’s children. Even they hadn’t spoken to their father in close to 25 years. When they arrived in the village of Lasserre, the recluse repeated his request for a revolver, so he could shoot himself. There was barely room to move in his dilapidated house. The corridors were lined with shelves heaving with flasks of mouldering liquids. Overgrown plants spilled out of pots everywhere. Thousands of pages of arcane scrawling were lined up in canvas boxes in his library. But his infirmity had put paid to his studies, and he no longer saw any purpose in life. On 13 November, he died exhausted and alone in hospital in the neighbouring town of St-Lizier.

The hermit’s name was Alexander Grothendieck. Born in 1928, he arrived in France from Germany as a refugee in 1939, and went on to revolutionise postwar mathematics as Einstein had physics a generation earlier. Moving beyond distinct disciplines such as geometry, algebra and topology, he worked in pursuit of a deeper, universal language to unify them all. At the heart of his work was a new conception of space, liberating it from the Euclidean tyranny of fixed points and bringing it into the 20th-century universe of relativity and probability. The flood of concepts and tools he introduced in the 1950s and 60s awed his peers.

Then, in 1970, in what he later called his “great turning point”, Grothendieck quit. Resigning from France’s elite Institut des Hautes Études Scientifiques (IHES) – in protest at funding it received from the ministry of defence – put an end to his high-level mathematics career. He occupied a few minor teaching posts until 1991, when he left his home underneath Provence’s Mont Ventoux and disappeared. No one – friends, family, colleagues, the intimates who knew him as “Shurik” (his childhood nickname, the Russian diminutive for Alexander) – knew where he was.

Grothendieck’s capacity for abstract thought is legendary: he rarely made use of specific equations to grasp at mathematical truths, instead intuiting the broader conceptual structure around them to make them surrender their solutions all at once. He compared the two approaches to using a hammer to crack a walnut, versus soaking it patiently in water until it opens naturally. “He was above all a thinker and a writer, who decided to apply his genius mostly to mathematics,” says Olivia Caramello, a 39-year-old Italian mathematician who is the leading proponent of his work today. “His approach to mathematics was that of a philosopher, in the sense that the way in which one would prove results was more important to him than the results themselves.”

In Lasserre, he lived in near-complete solitude, with no television, radio, phone or internet. A handful of acolytes trekked up to the village once his whereabouts filtered out; he politely refused to receive most of them. When he did exchange words, he sometimes mentioned his true friends: the plants. Wood, he believed, was conscious. He told Michel Camilleri, a local bookbinder who helped compile his writings, that his kitchen table “knows more about you, your past, your present and your future than you will ever know”. But these wild preoccupations took him to dark places: he told one visitor that there were entities inside his house that might harm him.

Grothendieck’s genius defied his attempts at erasing his own renown. He lurks in the background of one of Cormac McCarthy’s final novels, Stella Maris, as an eminence grise who leads on its psychically disturbed mathematician protagonist. The long-awaited publication in 2022 of Grothendieck’s exhaustive memoir, Harvests and Sowings, renewed interest in his work. And there is growing academic and corporate attention to how Grothendieckian concepts could be practically applied for technological ends. Chinese telecoms giant Huawei believes his esoteric concept of the topos could be key to building the next generation of AI, and has hired Fields medal-winner Laurent Lafforgue to explore this subject. But Grothendieck’s motivations were not worldly ones, as his former colleague Pierre Cartier understood. “Even in his mathematical milieu, he wasn’t quite a member of the family,” writes Cartier. “He pursued a kind of monologue, or rather a dialogue with mathematics and God, which to him were one and the same.”

Beyond his mathematics was the unknown. Were his final writings, an avalanche of 70,000 pages in an often near-illegible hand, the aimless scribblings of a madman? Or had the anchorite of Lasserre made one last thrust into the secret architecture of the universe? And what would this outsider – who had spurned the scientific establishment and modern society – make of the idea of tech titans sizing up his intellectual property for exploitation?

* * *

In a famous passage from Harvests and Sowings, Grothendieck writes that most mathematicians work within a preconceived framework: “They are like the inheritors of a large and beautiful house all ready-built, with its living rooms and kitchens and workshops, and its kitchen utensils and tools for all and sundry, with which there is indeed everything to cook and tinker.” But he is part of a rarer breed: the builders, “whose instinctive vocation and joy is to construct new houses”.

Now his son, Matthieu Grothendieck, is working out what to do with his father’s home. Lasserre lies on the top of a hill 22 miles (35km) north of the Spanish border, in the remote Ariège département, a haven for marginals, drifters and utopians. I first walk up there one piercingly cold January morning in 2023, mists cloaking forests of oak and beech, red kites surveying the fields in between. Grothendieck’s home – the only two-storey house in Lasserre – is at the village’s southern extremity. Hanging above the road beyond are the snow-covered Pyrenees: a promise of a higher reality.

Matthieu answers the door wearing a dressing gown, with the sheepish air of a man emerging from hibernation. The 57-year-old has deeply creased features and a strong prow of a nose. Inheriting the house where his father experienced such mental ordeals weighs on him. “This place has a history that’s bigger than me,” he says, his voice softened by smoking. “And as I haven’t got the means to knock it into shape, I feel bad about that. I feel as if I’m still living in my father’s house.”

A former ceramicist, he is now a part-time musician. In the kitchen, a long, framed scroll of Chinese script stands on a sideboard, next to one photograph of a Buddha sculpture and two of his mother, Mireille Dufour, whom Grothendieck left in 1970. (Matthieu is her youngest child; he has a sister, Johanna, and brother, Alexandre. Grothendieck also had two other sons, Serge and John, with two other women.) Above Matthieu’s bed is a garish portrait of his paternal grandfather, Alexander Schapiro, a Ukrainian Jewish anarchist who lost an arm escaping a tsarist prison, and later fought in the Spanish civil war.

Even with all his wisdom and the depth of his insight, there was always a sense of excessiveness about my father. He always had to put himself in danger

Schapiro and his partner, the German writer Johanna Grothendieck, left the five-year-old Grothendieck in foster care in Hamburg when they fled Nazi Germany in 1933 to fight for the socialist cause in Europe. He was reunited with his mother in 1939, and lived the remainder of the war in a French internment camp or in hiding. But his Jewish father, interned separately, was sent to Auschwitz and murdered on arrival in 1942. It was this legacy of abandonment, poverty and violence that drove the mathematician and finally overwhelmed him, Matthieu suggests: “Artists and geniuses are making up for flaws and traumas. The wound that made Shurik a genius caught up with him at the end of his life.”

Matthieu leads me into the huge, broken-down barn behind the house. Heaped on the bare-earth floor is a mound of glass flasks encased in wicker baskets: inside them are what remains of the mathematician’s plant infusions, requiring thousands of litres of alcohol. Far removed from conventional mathematics, Grothendieck’s final studies were fixated on the problem of why evil exists in the world. His last recorded writing was a notebook logging the names of the deportees in his father’s convoy in August 1942. Matthieu believes his father’s plant distillations were linked with this attempt to explain the workings of evil: a form of alchemy through which he was attempting to isolate different species’ properties of resilience to adversity and aggression. “It’s hard to understand,” says Matthieu. “All I know is that they weren’t for drinking.”

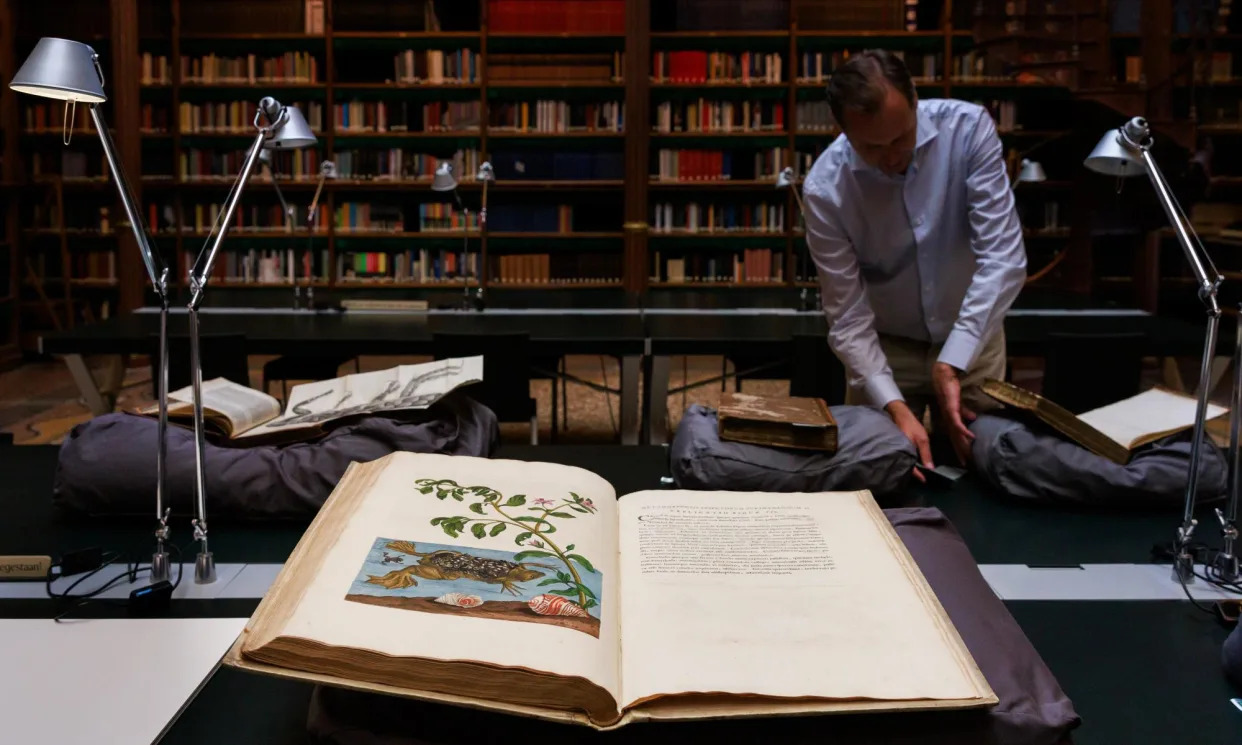

Later, Matthieu agrees to let me look at his father’s Lasserre writings – a cache of esoterica scanned on to hard disk by his daughter. At the start of 2023, the family were still negotiating their entry into the French national library; the writings have now been accepted and at some point will be publicly available for research. Serious scholarship is needed to decide their worth on mathematical, philosophical and literary levels. I’m definitely not qualified on the first count.

I open a first page at random. The writing is spidery; there are occasional multicoloured topological diagrams, namechecks of past thinkers, often physicists – Maxwell, Planck, Einstein – and recurrent references to Satan and “this cursed world”. His children are struggling to fathom this prodigious output, too. “It’s mystic but also down to earth. He talks about life with a form of moralism. It’s completely out of fashion,” says Matthieu. “But in my opinion there are pearls in there. He was the king of formulating things.”

After a couple of hours’ reading, head spinning, I feel the abyss staring into me. So imagine what it was like for Grothendieck. According to Matthieu, a friend once asked his father what his greatest desire was. The mathematician replied: “That this infernal circle of thought finally ceases.”

* * *

The colossal folds of Mont Ventoux’s southern flank are mottled with April cloud shadow as cyclists skirt the mountain. In the Vaucluse département of Provence, this is the terrain where Alexander Grothendieck took his first steps into mysticism. Now, another of his sons, Alexandre, lives in the area. I wander up a bumpy track to see the 62-year-old ambling out of oak woods, smiling, to meet me. Wearing a moth-eaten jumper, dark slacks and slippers, Alexandre is slighter than his brother, with wind-chafed cheeks.

He leads me into the giant hangar where he lives. It is piled with amps and instruments; at the back is a workshop where he makes kalimbas, a kind of African thumb piano. In 1980, his father moved a few kilometres to the west, to a house outside the village of Mormoiron. In the subsequent years, Grothendieck’s thoughts turned inwards towards bewildering spiritual vistas. “Even with all his wisdom and the depth of his insight, there was always a sense of excessiveness about my father,” says Alexandre. “He always had to put himself in danger. He searched for it.”

Grothendieck had abandoned the commune he had been part of since 1973 in a village north of Montpellier, where he still taught at the university. From 1970 onwards, he had been one of France’s first radical ecologists and became increasingly preoccupied with meditation. In 1979, he spent a year dwelling intensely on his parents’ letters, a reflection that stripped away any lingering romanticism about them. “The myth of their great love fell flat for Shurik – it was a pure illusion,” says Johanna Grothendieck, who bears her grandmother’s name. “And he was able to decrypt all the traumatic elements of his childhood. He realised he had been quite simply abandoned by his own mother.”

This preoccupation with the past intensified into the mid-1980s, as Grothendieck worked on the manuscript for Harvests and Sowings. A reflection on his mathematical career, it was filled with stunning aphoristic insights, like the house metaphor. But, choked with David Foster Wallace-like footnotes, it was relentless and overwhelming, too – and steeped in a sense of betrayal by his former colleagues. In the wake of his revelations about his parents, this feeling became a kind of governing principle. “It was a systematic thing with our papa – to put someone on a pedestal, in order to see their flaws. Then – bam! – they went down in flames,” says Alexandre.

Although he still produced some mathematical work during this period, Grothendieck delved further into mysticism. He looked to his dreams as a conduit to the divine; he believed they were not products of his own psyche, but messages sent to him by an entity he called the Dreamer. This being was synonymous with God; as he conceived it, a kind of cosmic mother. “Like a maternal breast, the ‘grand dream’ offers us a thick and savorous milk, good to nourish and invigorate the soul,” he later wrote in The Key of Dreams, a treatise on the subject. Pierre Deligne, the brilliant pupil he accused in Harvests and Sowings of betraying him, felt his old master had lost his way. “This was not the Grothendieck I admired,” he says, on the phone from Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study.

He became totally isolated. He was no longer in contact with nature. He had cut ties with everyone

By summer 1989, the prophetic dreams had intensified into daily audiences, “absorbing almost all of my time and energy”, with an angel Grothendieck called either Flora or Lucifera, depending on whether she manifested as benevolent or tormenting. She tutored him in a new cosmology, central to which was the question of suffering and evil in God’s greater scheme. He believed, for example, that the speed of light being close to, but not precisely, 300,000km a second, was evidence of Satan’s interference. “He was in a form of mystic delirium,” says another former pupil, Jean Malgoire, now a professor at Montpellier University. “Which is also a form of mental illness. It would have been good if he could have been seen by a psychiatrist at that point.”

In real life, he had become forbidding and remote. Matthieu spent two months in Mormoiron working on the house; during that time, his father invited him in only once. His son blew his top: “He’d lost interest in others. I could no longer feel any authentic or sincere empathy.” But Grothendieck was still interested in people’s souls. On 26 January 1990, he sent 250 of his acquaintances – including his children – a messianic, seven-page typed epistle, entitled Letter of the Good News. He announced a date – 14 October 1996 – for the “Day of Liberation” when evil on Earth would cease, and said they had been chosen to help usher in the new era. It was “a kind of remake of the most limited aspects of Christianity”, says Johanna.

Then in June 1990, as if to firm up his spiritual commitment, Grothendieck fasted for 45 days (he wanted to beat Christ’s 40), cooling himself in the heat of summer in a wine barrel filled with water. As he watched his father shrivel to an emaciated frame reminiscent of the Nazi concentration camp prisoners, Alexandre realised he may have been emulating someone else: “In some way, he was rejoining his father.”

Grothendieck almost died. He only relented when persuaded to resume eating by Johanna’s partner. She believes the fast damaged her father’s brain on a cellular level in a way impossible for a 62-year-old to recover from, further loosening his grip on rationality. Shortly afterwards, he summoned Malgoire to Mormoiron to collect 28,000 pages of mathematical writings (now available online). He showed his student an oil drum full of ashes: the remains of a huge raft of personal papers, including his parents’ letters, he had burned. The past was immaterial, and now Grothendieck could only look ahead. One year later, without warning, he moved away from his house on a trajectory known only to him.

* * *

A circular slab of black pitted sandstone, fashioned by Johanna and now smothered in wild roses, marks Grothendieck’s resting place in Lasserre churchyard. It’s almost hidden behind a telegraph post. The mathematician was alone when he died in hospital; after several weeks in their company, he had spurned his children again, only accepting care from intermediaries.

The presence of his family seemed to stir up unbearable feelings. In his writings, he evaluates the people in his life for how much they are under the sway of Satan. But, as Alexandre points out, this was also a projection of his own seething unconscious: “He didn’t like what he saw in the mirror we held out to him.”

They only discovered his whereabouts in Lasserre by accident: one day in the late 90s Alexandre signed up for car insurance, and the company said they already had an address for an Alexander Grothendieck on file. Deciding to make contact, Alexandre spotted his father across the marketplace in the town of St-Girons, south of Lasserre. “Suddenly, he sees me,” says Alexandre. “He’s got a big smile, he’s super-happy. So I said to him: ‘Let me take your basket.’ And all of a sudden, he has a thought that he shouldn’t have anything to do with me, and his smile turns the other way. It lasted a minute and a half. A total cold shower.” He didn’t see his father again until the year he died.

At least until the early 00s, Grothendieck worked at a ferocious pace, often writing up the day’s “meditation” at the kitchen table in the dead of night. “He became totally isolated. He was no longer in contact with nature. He had cut ties with everyone,” says Johanna.

He vacillated about the date of the Day of Liberation, when evil on Earth would cease. Recalculating it as late August or early September 1996 instead of the original October date, he was crestfallen at the lack of celestial trumpets. Mathematicians Leila Schneps and Pierre Lochak, who had tracked him down a year earlier, visited him the day afterwards. “We delicately said: ‘Perhaps it’s started and people’s hearts are opening.’ But obviously he believed what we believed, which was that nothing had happened,” Schneps says.

Experiencing an “uncontrollable antipathy” to his work, that he attributed to malign forces but sounds a lot like depression, he wrote in early 1997: “The most abominable thing in the fate of victims is that Satan is master of their thoughts and feelings.” He contemplated suicide for several days, but resolved to continue living as a self-declared victim.

The house was weighing on him. In 2000, he offered it to his bookbinder, Michel Camilleri, for free, deeming him the perfect candidate because he was “good with materials”. The sole condition was that Camilleri look after his plant friends. When Camilleri refused, he was outraged – seeing the hand of Satan once more. A year later, the building was nearly destroyed when his unswept stove chimney caught fire. Some witnesses say Grothendieck tried to prevent the firefighters from accessing his property (Matthieu doesn’t believe this).

The curate at Lasserre church, David Naït Saadi, wrote Grothendieck a letter in around 2005, attempting to bring the hermit into the community. But Grothendieck fired back a missive full of biblical references, saying Saadi had a “viper’s tongue” and that he should nail his reply to the church noticeboard.

By the mid-00s, his writing was petering out. The endpoint of his late meditations, according to Matthieu, is a chronicle in which his father painstakingly records everything he is doing, as if the minutiae of his own life are imbued with immanence. Matthieu finds these writings so painful to read that he kept them back from the national library donation. Grothendieck was lost in the rooms and corridors of his own mind.

* * *

In mid-April, dapper Parisians are filing out of the polished foyer of a redeveloped hotel in the seventh arrondissement, heading for lunch. The first French TV programmes were broadcast from the building; now, Huawei is pushing for a similar leap in AI here. It has set up the Centre-Lagrange, an advanced mathematics research institute, on the site and hired elite French mathematicians, including Laurent Lafforgue, to work there. An aura of secrecy surrounds their work in this ultra-competitive field, compounded by growing suspicion in the west of Chinese tech. Huawei initially refuse to answer any questions, before permitting some answers to be emailed.

Grothendieck’s notion of the topos, developed by him in the 1960s, is of particular interest to Huawei. Of his fully realised concepts, toposes were his furthest step in his quest to identify the deeper algebraic values at the heart of mathematical space, and in doing so generate a geometry without fixed points. He described toposes as a “vast and calm river” from which fundamental mathematical truths could be sifted. Olivia Caramello views them rather as “bridges” capable of facilitating the transfer of information between different domains. Now, Lafforgue confirms via email, Huawei is exploring the application of toposes in a number of domains, including telecoms and AI.

Caramello describes toposes as a mathematical incarnation of the idea of vision; an integration of all the possible points of view on a given mathematical situation that reveals its most essential features. Applied to AI, toposes could allow computers to move beyond the data associated with, say, an apple; the geometric coordinates of how it appears in images, for example, or tagging metadata. Then AI could begin to identify objects more like we do – through a deeper “semantic” understanding of what an apple is. But practical application to create the next generation of “thinking” AI is, according to Lafforgue, some way off.

A larger question is whether this is what Grothendieck would have wanted. In 1972, during his ecologist phase, concerned that capitalist society was driving humanity towards ruin, he gave a talk at Cern, near Geneva, entitled Can We Continue Scientific Research? He didn’t know about AI – but he was already opposed to this collusion between science and corporate industry. Considering his pacifist values, he would probably also have been opposed to Huawei’s championing of his work; its chief executive, Ren Zhengfei, is a former member of the People’s Liberation Army engineering corps. The US department of defense, as well as some independent researchers, believes Huawei is controlled by the Chinese military.

Huawei insists it is a private company, owned by its employees and its founding chairman, Ren Zhengfei, and that it is “not owned, controlled or affiliated to any government or third-party company”.

We are at the very beginning of a huge exploration of these manuscripts. And certainly there will be marvels in them

Lafforgue points out that France’s IHES, where Grothendieck and later he worked, was funded by industrial companies – and thinks Huawei’s interest is legitimate. Caramello, who is the founder and president of the Grothendieck Institute research organisation, believes that he would have wanted a systematic exploration of his concepts to bring them to fruition. “Topos theory is itself a kind of machine that can extend our imagination,” she says. “So you see Grothendieck was not against the use of machines. He was against blind machines, or brute force.” What is unsettling is a degree of opaqueness about Huawei’s aims regarding AI and its collaborations, including its relationship with the Grothendieck Institute, where Lafforgue sits on the scientific council. But Caramello stresses that it is an entirely independent body that engages in theoretical, not applied research, and that makes its findings available to all. She says it does not research AI and that Lafforgue’s involvement pertains solely to his expertise in Grothendieckian maths.

Matthieu Grothendieck is clear about whether his father would have consented to Huawei, or any other corporation, exploiting his work: “No. I don’t even ask. I know.” There is little doubt that the mathematician believed modern science had become morally stunted, and the Lasserre papers attempted to reconcile it with metaphysics and moral philosophy. Compared with Grothendieck’s delirious 1980s mysticism, there is structure and intent here. They begin with just under 5,000 pages devoted to the Schematic Elemental Geometry and Structure of the Psyche. According to the mathematician Georges Maltsiniotis, who has examined this portion, these sections contain maths in “due and proper form”. Then Grothendieck gets going on the Problem of Evil, which sprawls over 14,000 pages undertaken during much of the 1990s.

Judging by the 200 or so pages I attempt to decipher, Grothendieck put herculean effort into his new cosmology. He seems to be trying to fathom the workings of evil at the level of matter and energy. He squabbles with Einstein, James Clerk Maxwell and Darwin, especially about the role of chance in what he viewed as a divinely created universe. There are numerological musings about the significance of the lunar and solar cycles, the nine-month term of a pregnancy. He renames the months in a new calendar: January becomes Roma, August becomes Songha.

How much of this work is meaningful and how much empty mania? For Pierre Deligne, Grothendieck became fatally unmoored in his solitude. He says that he has little interest in reading the Lasserre writings “because he had little contact with other mathematicians. He was restricted to his own ideas, rather than using those of others too.” But it’s not so clear-cut for others, including Caramello. In her eyes, this fusion of mathematics and metaphysics is true to his boundary-spanning mind and could yield unexpected insights: she points out his use of the mathematics of vibration to explain psychological phenomena in Structure of the Psyche. “We are at the very beginning of a huge exploration of these manuscripts. And certainly there will be marvels in them,” she says.

Grothendieck remained hounded by evil until the end. Perhaps, shattered by his traumas, he couldn’t allow himself to forgive, and to conceive of the world in a kinder light. But his children, despite the long estrangement, aren’t the same. Matthieu rejects the idea that his father repeated the abandonment he suffered as a child on them: “We were adults, so it’s nothing compared to what he went through. He did a lot better than his parents.”

The shunning of his children wounded Johanna, but she understands that something was fundamentally broken in her father. “In his mind, I don’t think he left us. We existed in a parallel reality for him. The fact that he burned his parents’ letters was extremely revealing: he had no feeling of existing in the family chain of generations.” What’s striking is the trio’s lack of judgment about their father and their openness to discussing his ordeals. “We accept it,” says Alexandre. “It was the trial he wanted to inflict on himself – and he inflicted it on himself most of all.”