A Cracked Piece of Metal Healed Itself in Experiment That Stunned Scientists

(Luis Diaz Devesa/Moment/Getty Images)

(Luis Diaz Devesa/Moment/Getty Images)File this under 'That's not supposed to happen!'. In an experiment, scientists observed a metal healing itself. If this process can be fully understood and controlled, we could be at the start of a whole new era of engineering.

In a study published last year, a team from Sandia National Laboratories and Texas A&M University was testing the resilience of the metal, using a specialized transmission electron microscope technique to pull the ends of the metal 200 times every second.

They then observed the self-healing at ultra-small scales in a 40-nanometer-thick piece of platinum suspended in a vacuum.

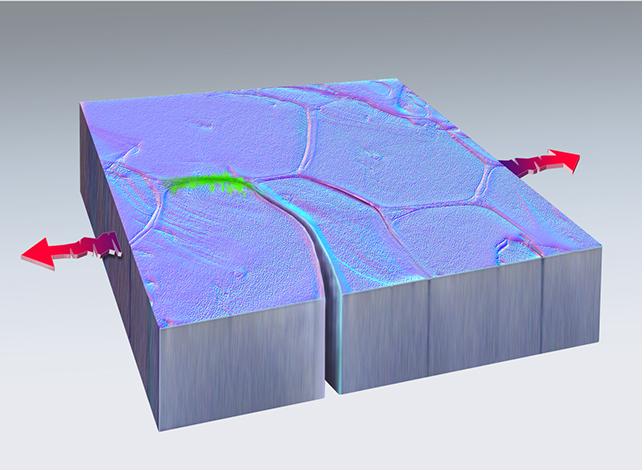

Cracks caused by the kind of strain described above are known as fatigue damage: repeated stress and motion that causes microscopic breaks, eventually causing machines or structures to break.

Amazingly, after about 40 minutes of observation, the crack in the platinum started to fuse back together and mend itself before starting again in a different direction.

"This was absolutely stunning to watch first-hand," said materials scientist Brad Boyce from Sandia National Laboratories when the results were announced.

"We certainly weren't looking for it. What we have confirmed is that metals have their own intrinsic, natural ability to heal themselves, at least in the case of fatigue damage at the nanoscale."

These are exact conditions, and we don't know yet exactly how this is happening or how we can use it. However, if you think about the costs and effort required for repairing everything from bridges to engines to phones, there's no telling how much difference self-healing metals could make.

While the observation is unprecedented, it's not wholly unexpected. In 2013, Texas A&M University materials scientist Michael Demkowicz worked on a study predicting that this kind of nanocrack healing could happen, driven by the tiny crystalline grains inside metals essentially shifting their boundaries in response to stress.

Demkowicz also worked on this study, using updated computer models to show that his decade-old theories about metal's self-healing behavior at the nanoscale matched what was happening here.

That the automatic mending process happened at room temperature is another promising aspect of the research. Metal usually requires lots of heat to shift its form, but the experiment was carried out in a vacuum; it remains to be seen whether the same process will happen in conventional metals in a typical environment.

A possible explanation involves a process known as cold welding, which occurs under ambient temperatures whenever metal surfaces come close enough together for their respective atoms to tangle together.

Typically, thin layers of air or contaminants interfere with the process; in environments like the vacuum of space, pure metals can be forced close enough together to literally stick.

"My hope is that this finding will encourage materials researchers to consider that, under the right circumstances, materials can do things we never expected," said Demkowicz.

The research was published in Nature.

An earlier version of this article was published in July 2023.