Daria Isachenko

Erol Kaymak

doi:10.18449/2024C39

PDF | 352 KB

EPUB | 1.2 MB

MOBI | 3.1 MB

LONG READ

In the Black Sea, Turkey has been able to engage in resource exploration and joint security arrangements with its neighbours. Ankara’s approach to the Black Sea demonstrates that with the right diplomatic efforts and mutual recognition of interests, regional cooperation is possible even in complex geopolitical environments. The contrast in Ankara’s positioning in the Black Sea and the Eastern Mediterranean highlights the potential for Turkey to participate in cooperative frameworks in the latter case, provided its concerns and interests are adequately addressed.

In the Black Sea, Turkey has managed to establish a functioning modus operandi with all the riparian states. Ankara’s strategy emphasises regional ownership, multilateral cooperation, and a balancing act to prevent domination by any single power. Although Turkey did not join the Western-led sanctions regime against Russia, Ankara’s steps in the Black Sea region, such as its application of the Montreux Convention, its initial mediation efforts between Russia and Ukraine, the Black Sea Grain Deal, as well as the trilateral Black Sea Mine Countermeasures Task Force with Romania and Bulgaria, have been welcomed by the West.

In the Eastern Mediterranean, however, the balance between Turkey being a partner or a challenger to its Western allies is rather different. Following Ankara’s controversial drilling activities in 2020, Josep Borrell, the High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and Vice President of the European Commission, stated that “the three old Empires: Russia, China and Turkey … come as threats or Global rivals” for Europe. It is also in the context of the Eastern Mediterranean that Turkey’s policy is often described as expansionist and revisionist.

Comparing and contrasting Turkey’s Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean policies, we can observe that one of Ankara’s key problems in the latter case is its sense of exclusion from having a say in regional discussions. The Eastern Mediterranean nexus of conflicts also shows that one of the dominant approaches in Ankara’s foreign policy is to assert its interests “both on the ground and at the table” (hem sahada, hem de masada). A driving logic behind this is that in order to sit at the table, one must be present on the ground. The desire to be at the table stems from Ankara’s sense of entitlement to regional ownership. While Ankara has been able to achieve this in the Black Sea, it is still struggling to negotiate its share in the regional dynamics of the Eastern Mediterranean.

Asserting interests: “Both on the ground and at the table”

Turkey’s foreign policy in recent years has been characterised by striving for strategic autonomy, which has been analysed by experts through various lenses. First, it has been applied in the context of Turkey-West relations and its balancing act, implying Ankara’s aim to diminish Turkey’s dependence on the West, especially in the security sphere. Second, Ankara’s quest for strategic autonomy has also been viewed as a defence-oriented maritime strategy to protect national interests and extend the concept of homeland to maritime zones. Yet others have interpreted Ankara’s strategic autonomy based on a neo-Ottoman foreign policy to enhance Turkey’s influence as a regional power.

What is common to these perspectives is the idea of Ankara asserting its agency while aiming to secure its interests and shape regional developments. It does so through a combination of military presence and diplomatic engagement. By projecting military power, forging strategic partnerships, and challenging existing arrangements, Turkey seeks to demonstrate its capacity to be a decisive actor in regional affairs. This assertive approach reflects Ankara’s refusal to be excluded from regional decision-making processes. Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s statement, “We are now a country with a fundamental place both on the ground and at the table,” underscores Turkey’s ambition to be a central player in regional politics and in the international arena.

Turkey’s actions in the Eastern Mediterranean are a clear demonstration of its “on the ground” strategy, including naval exercises, deploying drilling ships in contested waters, and signing a maritime boundary agreement with Libya in 2019. Ankara’s aim has been to secure its claims to maritime resources and to counter perceived encroachments by Greece and Cyprus, supported by the European Union (EU) and the United States (US). Furthermore, Turkey’s exclusion from regional initiatives, such as the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum, exemplifies the challenges it faces in being recognised as a legitimate stakeholder at the table. This fuels Turkey’s assertive approach, based on its perception of being deliberately sidelined. As Erdoğan stated back in 2020, “Turkey, much like a century ago and half a century ago, is facing attempts to be excluded from the re‑establishment of the world order.”

Unlike the Eastern Mediterranean, the Black Sea regional order gives Turkey a key role in shaping it as well as acting as a regional stabiliser. Ankara’s diplomatic efforts focus on maintaining regional stability and preventing external interference, primarily through the strategic implementation of the Montreux Convention. By leveraging the Montreux Convention, Turkey has limited the influence of non-riparian states and maintains a balanced power dynamic, preventing any single actor from dominating the region. This has allowed Turkey to play an influential role in the Black Sea’s security architecture, balancing its relationships with both the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and Russia to maximise its strategic autonomy and regional influence.

Regional ownership in the Black Sea

One of the key elements of Turkey’s Black Sea policy has been the idea of regional ownership. It has been applied in different ways. First, it has meant multilateral institutionalised cooperative frameworks involving all riparian states, such as the Organization of Black Sea Economic Cooperation (BSEC) as well as maritime missions like the Black Sea Naval Cooperation Task Group (BlackSeaFor) and the Black Sea Harmony. Second, the notion of regional ownership has increasingly aligned with a Turkish-Russian ‘condominium’, reflecting Turkey’s careful approach to avoid antagonising Russia, alongside Moscow’s reliance on Ankara’s objective to restrict the involvement of non-regional actors.

After February 24, 2022, the idea of regional ownership has been seriously questioned in the West, given the impossibility of a formal multilateral framework that simultaneously engages all riparian states in the Black Sea and given Ankara’s own unease with Russia’s territorial expansion. Such a perspective assumes that for regional ownership to function, it must be formal and institutionalised or be exclusively about the Turkey-Russia partnership.

To understand Ankara’s approach in neighbouring regions, it is useful to look at one of the key assumptions behind regional ownership, namely ‘regional responsibility’, which forms the basis of Ankara’s sense of entitlement to shape regional affairs. This is also reflected in the “regional solutions to regional problems” approach that Turkey has promoted elsewhere, from the South Caucasus to Africa.

Broadly conceived, the idea of regional ownership comprises two fundamental elements that guide Ankara’s positioning. First, countries of the region should be included in regional affairs. Second, countries of the region should have a greater say than non-regional players. Thus, while Ankara has been able to exercise its regional responsibility in the Black Sea, the denial of regional ownership has been a driving factor behind Turkey’s policies in the case of the Eastern Mediterranean.

Challenges of regional ownership in the Eastern Mediterranean

The Eastern Mediterranean has become a focal point of geopolitical tensions, legal disputes, and economic opportunities, particularly following the discovery of significant natural gas reserves. The region’s complex dynamics are influenced by historical legacies, strategic interests, and the necessity of balancing regional and international relations. The multifaceted challenges of regional ownership in the Eastern Mediterranean have prompted a focus on the actions and foreign policy of Turkey and the contrasting perspectives surrounding these issues.

Many policy perspectives from Western institutions view Turkey’s actions in the Eastern Mediterranean as increasingly assertive. Critics argue that Turkey’s maritime claims, military presence, and energy exploration activities in disputed waters contribute to regional tensions and undermine international law. These concerns are often framed within the context of Turkey’s strained relations with its NATO allies and the EU.

From this perspective, Turkey’s exclusion from regional cooperation frameworks like the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum is viewed as stemming from its aggressive behaviour and unwillingness to compromise. Western policy analysts often emphasise the importance of upholding international law, particularly the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), and call for Turkey to align its claims and actions with international norms. They argue that Turkey’s actions violate both the spirit and the letter of UNCLOS, which seeks to provide a fair and equitable framework for maritime boundary delimitation for all parties involved. This perceived disregard for international norms and agreements heightens fears of further instability in a region already fraught with historical rivalries and territorial disputes.

Policy recommendations from this viewpoint typically involve a combination of diplomatic pressure, economic sanctions, and support for regional cooperation initiatives that exclude or marginalise Turkey. The goal is to compel Turkey to modify its behaviour and accept a more limited role in the Eastern Mediterranean, in line with the preferences of the EU, the US, and regional allies like Greece, Cyprus, and Israel. By leveraging economic sanctions and diplomatic isolation, Western policymakers aim to incentivise Turkey to adhere to international legal frameworks and to participate in multilateral negotiations that uphold the rule of law and respect for sovereign boundaries.

Ankara’s view of the Eastern Mediterranean order and its search for riparian allies

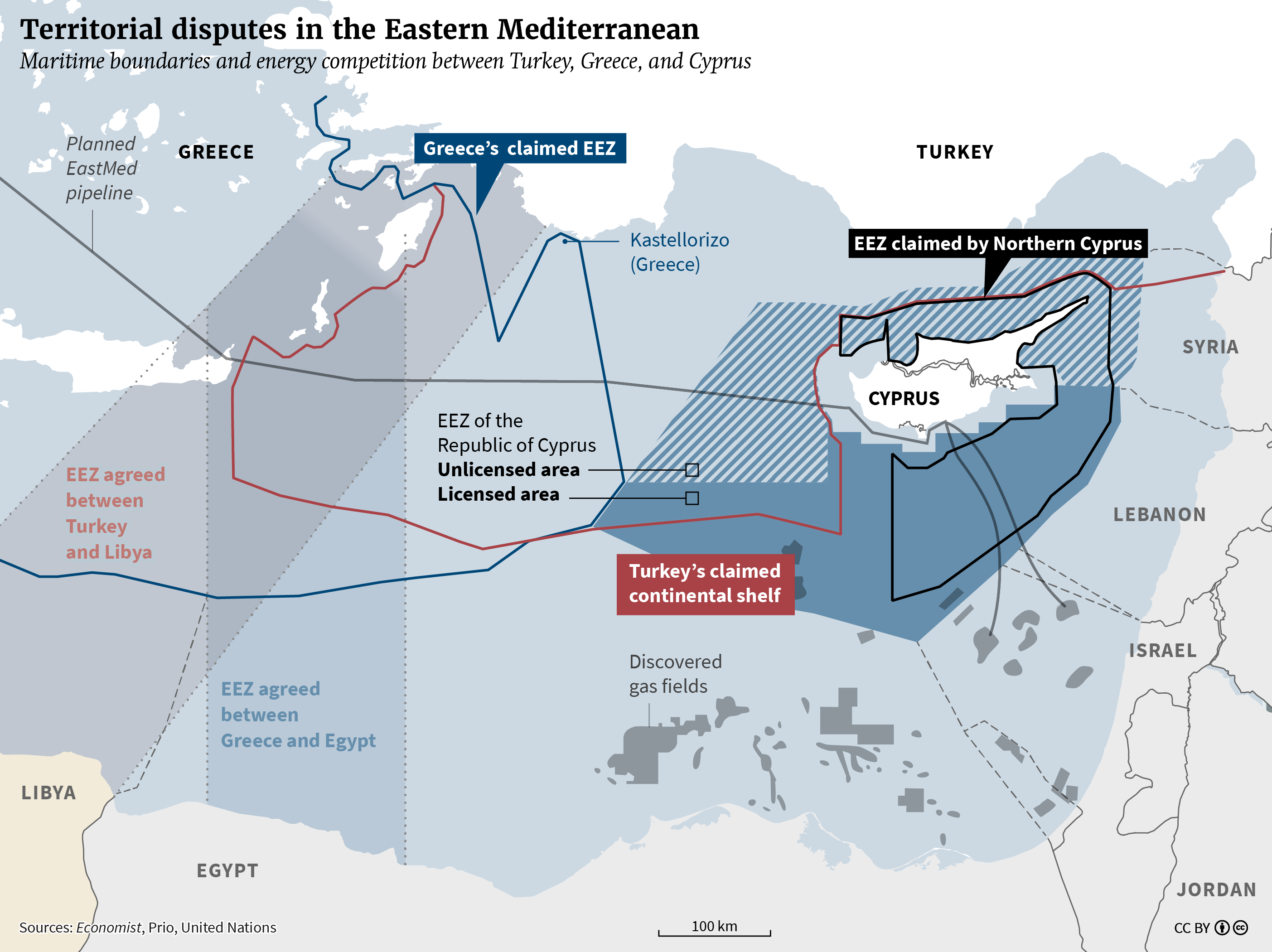

Map

Source: Sinem Adar et al., Visualizing Turkey’s Foreign Policy Activism (Berlin: Centre for Applied Turkey Studies [CATS], CATS Network, 20 August 2021), Figure 5, https://www.cats-network.eu/topics/visualizing-turkeys-foreign-policy-activism

Turkey’s assertiveness is driven by a combination of factors, including its long-standing maritime disputes with Greece and Cyprus, its desire to secure a share of the region’s energy resources, and its concerns over the formation of alliances that, in Ankara’s view, could isolate or contain Turkey. These strategic concerns are compounded by the legacy of historical treaties, such as the Lausanne Treaty, which have left unresolved tensions and competing claims over maritime boundaries and sovereignty.

In particular, Greece’s militarisation of islands initially demilitarised by the Lausanne Treaty is seen by Turkey as a violation of historical agreements, exacerbating fears of encirclement and strategic vulnerability. Greece has established military installations on several Aegean islands, including Lesbos, Chios, Samos, Ikaria, and the Dodecanese group (such as Rhodes, Kos, Leros, and Kalymnos), which Turkey contends violates the demilitarisation clauses of the Treaties of Lausanne (1923) and Paris (1947). These installations typically consist of army barracks, radar stations, coastal artillery, and defensive fortifications designed for monitoring and defence against potential threats. While Greece justifies this militarisation as necessary for self-defence, citing Article 51 of the United Nations Charter and the proximity of these islands to the Turkish coast, Turkey views it as a breach of international agreements and a security threat. The presence of these military facilities remains a significant point of diplomatic contention between the two countries.

In this context, Turkey’s signing of the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Libya in November 2019 is particularly significant. Given Turkey’s lack of partners in the Eastern Mediterranean, it has been Ankara’s strategic move to turn Libya into a “riparian” ally to counter regional isolation and assert its maritime claims. By establishing a maritime boundary with Libya, Turkey aims to challenge efforts by Greece and Cyprus to unilaterally delimit their maritime zones and to establish a foothold in the region’s energy dynamics. This is not merely about immediate territorial gains, but is also a bid to reshape the regional order in a way that acknowledges Turkey’s strategic importance and historical grievances. The MoU serves as both a defensive measure to protect Turkey’s interests and an offensive strategy to project its power and influence in the Eastern Mediterranean.

By forming an alliance with Libya, Turkey also sought to counterbalance the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum, which includes Cyprus, Egypt, France, Greece, Israel, Italy, Jordan, and the Palestinian Authority. The MoU strategically positions Turkey as a key player in the region’s energy politics, potentially disrupting plans to transport Eastern Mediterranean gas to European markets via routes that bypass Turkey. Additionally, the MoU underscores Turkey’s broader strategy of using bilateral agreements to assert its claims and also challenges what it perceives as an exclusionary regional order. This move has drawn criticism and increased tensions, but also highlights Turkey’s determination to defend its interests through proactive and sometimes controversial measures, particularly against the backdrop of unilateral actions by Greece and Cyprus to delimit their maritime zones without considering Turkish and Turkish Cypriot rights.

Continuities in Turkish foreign policy

Domestically, President Erdoğan’s rapprochement with military and nationalist elements following the 2016 coup attempt has reinforced a confrontational and nationalistic foreign policy. The “survival of the state” coalition emphasises a strong state capable of defending its sovereignty and interests against perceived external threats. This coalition supports the Blue Homeland doctrine (Mavi Vatan), which advocates for extensive Turkish claims in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Former Chief of Staff of the Turkish Navy Rear Admiral Cihat Yaycı, a key proponent of the Blue Homeland doctrine, argues for an assertive stance to protect Turkey’s maritime rights. He emphasises the importance of securing Turkey’s access to natural resources and countering Greek claims. Yaycı’s views reflect a broader consensus among Turkish nationalists that Turkey must robustly defend its maritime boundaries and resource rights to ensure national security and economic prosperity. Admiral Cem Gürdeniz, another prominent figure, also supports a strong naval presence to safeguard Turkey’s interests. Both figures have played crucial roles in shaping Turkey’s maritime strategy, advocating for a proactive and sometimes confrontational approach to maritime disputes.

Turkey’s approach towards the Black Sea and the Eastern Mediterranean is not solely driven by current leadership. It is rooted in long-standing strategic considerations. In the Black Sea, Turkey’s balancing act between its NATO commitments and its desire to maintain stable relations with Russia has been one of the defining features of its regional strategy.

Blue Homeland Doctrine

The Blue Homeland (Mavi Vatan) is Turkey’s maritime strategy to expand and secure its sovereign rights in the Eastern Mediterranean, Aegean Sea, and Black Sea. Developed by Turkish naval officers, particularly Admiral Cem Gürdeniz. The doctrine has gained prominence under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s administration as part of Turkey’s broader strategic autonomy and assertive foreign policy.

Context and Evolution

Cold War Legacy: Rooted in Turkey’s Cold War-era naval strategy, which prioritised controlling sea routes and safeguarding maritime borders.

Post-2016 Shift: Following the 2016 coup attempt, there was a notable shift towards a more nationalist and assertive foreign policy, with the Blue Homeland doctrine becoming central to Turkey’s maritime strategy.

Geopolitical Dynamics: The discovery of energy resources in the Eastern Mediterranean and the evolving security environment in the Black Sea have further propelled the doctrine’s importance in Turkish policy.

Key Objectives

Maritime Sovereignty: Protect maritime claims and resources.

Strategic Autonomy: Enhance naval capabilities and reduce reliance on Western alliances.

Regional Influence: Establish Turkey as a dominant maritime power.

Key Components

Expansion of Claims: Extending Turkey’s maritime boundaries.

Naval Presence: Deploying forces and conducting exercises.

Strategic Partnerships: Agreements like the 2019 maritime boundary treaty with Libya.

Impact

The doctrine has increased regional tensions, particularly with Greece and Cyprus, and strained relations with NATO and the EU.

For more information see: Serhat Süha Çubukçuoğlu, Turkey’s Naval Activism: Maritime Geopolitics and the Blue Homeland Concept, Palgrave Studies in Maritime Politics and Security (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023).

The Eastern Mediterranean is likely to hold greater strategic significance for Turkey compared to the Black Sea. It is no coincidence that the Blue Homeland doctrine has emerged and been promoted in the official discourse in the Eastern Mediterranean context. The region’s energy resources, maritime disputes, and Turkey’s ambition to establish itself as a regional power make it a lasting top priority for Ankara.

The Blue Homeland doctrine and the “on the ground and at the table” approach are thus extensions of Turkey’s traditional foreign policy objectives, which prioritise the protection of its sovereignty, the assertion of its regional influence, and the pursuit of its economic interests. Future Turkish governments are likely to maintain a similar stance in these regions, albeit with potential adjustments based on a changing geopolitical environment.

Outlook and recommendations

Turkey’s actions in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea will have implications for its relationships with the US, the EU, and NATO. By pursuing a balanced and constructive approach, Turkey could leverage its regional influence to enhance its global standing and advance its strategic objectives. However, if Turkey’s security and economic interests remain unaddressed, it may resort to more assertive actions on the ground rather than at the table. An escalation of tensions could strain Turkey’s relationships with regional partners and Western allies, potentially leading to diplomatic and economic consequences. To mitigate these risks, Turkey should balance its assertive posture with diplomatic efforts to find mutually acceptable solutions to regional disputes.

Given the geostrategic interconnectedness between the Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, it is also essential for Ankara’s Western allies to try to engage constructively with Turkey to address its concerns and find common ground. In particular, this may involve revisiting existing agreements and frameworks, such as the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum, to ensure that such initiatives are representative, inclusive, and responsive to the needs of all regional stakeholders.

Despite Turkey’s geostrategic location and its potential to diversify energy routes to Europe, political tensions and concerns over Turkey’s assertive foreign policy have hindered closer cooperation with the EU. This has led Turkey to seek alternative alliances and secure its energy interests by adopting confrontational policies. These dynamics underscore the interplay between energy security, geopolitical competition, and regional stability, highlighting the need for a more integrated and cooperative approach to energy politics.

Dr Daria Isachenko is Associate at the Centre for Applied Turkey Studies (CATS).

The Centre for Applied Turkey Studies (CATS) is funded by Stiftung Mercator and the German Federal Foreign Office

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This Comment reflects the authors’ views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

DOI: 10.18449/2024C39