Tariffs ‘Protect Insiders, While Americans Pay The Price – Analysis

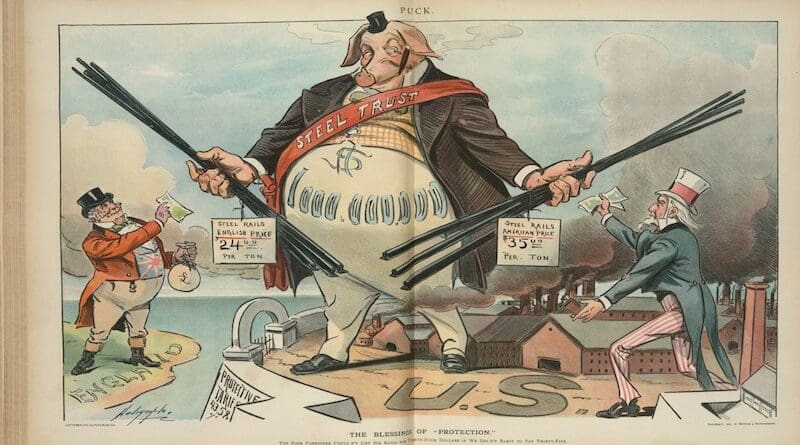

“The Blessings of Protection,” lithograph criticizing steel industry tariffs. Louis Dalrymple. Puck, 1901. Original caption: “The poor foreigner couldn’t get his rails for Twenty-four dollars if we didn’t elect to pay thirty-five.”

By AIER

By Vance Ginn

Tariffs, often promoted as a tool to protect American jobs and industries, are a hidden tax that disproportionately burdens consumers and producers alike. Both the Trump and Biden administrations have embraced these protectionist policies, and future administrations may likely do the same. But these policies do more harm than good, undermining the very people they are designed to protect.

Recently, protectionist policies have been championed by the Trump-Pence administration, continued by the Biden-Harris administration, and likely doubled down upon by Trump-Vance or Harris-Walz. Tariffs may seem like a good way to shield domestic industries from foreign competition by making imports more expensive, but the reality is starkly different. Tariffs are taxes on imports; like all taxes, the costs are inevitably passed down to the consumer. When the federal government imposes tariffs, it raises the prices of goods that many American businesses rely on, leading to higher costs. This isn’t just an abstract economic concept — it affects every American who buys a car, electronics, groceries, or other everyday items.

In 2023, the US imported over $3.8 trillion of goods and services while exporting $3.05 trillion. This nearly $7 trillion in trade volume highlights how imports and exports play a role in the US economy, supporting millions of American jobs, but is a relatively small share of the $27.3 trillion economy. While the US ran a current account deficit as imports exceeded exports by $773.4 billion in 2023, this amount doesn’t tell the whole story.

For instance, the US had significant trade surpluses with regions like South and Central America ($54.9 billion) and countries like the Netherlands ($43.7 billion) and Hong Kong ($23.6 billion). Conversely, it recorded deficits with China ($279.4 billion), the European Union ($208.2 billion), and Mexico ($152.4 billion). Notably, while substantial, trade with China represents only 8.4 percent of the total US international trade volume, even as it accounts for 36 percent of the current account deficit. This deficit and the total trade deficit are met with a capital account surplus, with funds flowing into the US, including investments that help finance the national debt, support lower interest rates, and support capital to businesses.

International trade provides mutually beneficial exchanges between people in different countries, supporting peace and prosperity.

The Real Economic Impact of Tariffs

Proponents of tariffs often argue they are necessary to rebuild America’s manufacturing sector, but the problem isn’t foreign competition — it’s at home. US manufacturers’ core issues stem from excessive government spending, high taxes, inflated minimum wages, overregulation, and a lack of right-to-work laws. Instead of addressing these root causes, tariffs exacerbate the problems by acting as an additional tax on American businesses and consumers.

When tariffs are imposed, the costs of imported goods rise. These goods are finished products, raw materials, and components that American producers rely on in their supply chains. This increased cost of production ripples through the economy, making American goods more expensive both domestically and internationally and hurting US businesses’ ability to compete.

Take, for example, the tariffs on steel, which were implemented to protect US steel producers. While they may have helped some steel manufacturers, they raised costs for industries that depend on steel, such as the automotive and construction sectors. These industries were forced to pass on these costs to consumers, making American-made goods more expensive and less competitive. Rather than revitalizing manufacturing, these tariffs hinder growth, slow job creation, and harm consumers.

Moreover, tariffs fail to address the real reasons behind the loss of manufacturing jobs. Automation and technological advances have displaced many jobs, allowing US manufacturing output to reach record highs with fewer workers. The Rust Belt’s loss of manufacturing jobs is less about foreign competition and more about the evolving nature of the global economy, tariffs do nothing to solve these domestic challenges.

When tariffs increase, they tax what we purchase from other countries. This tax directly affects producers and consumers who rely on foreign goods. The process reduces the demand for foreign currencies to purchase foreign goods while raising demand for the dollar, especially when the federal government runs deficits that result in higher interest rates. This results in an appreciated dollar by roughly the size of the tariff itself. This currency appreciation helps keep the cost of the taxed goods from rising too quickly, but it simultaneously disrupts the supply chain and other factors of production. As the dollar appreciates, US exports become more expensive for foreign buyers, leading to fewer exports and more imports. This dynamic undermines the goal of balancing or reducing the trade deficit with the targeted country or others.

Moreover, foreign countries often respond with retaliatory tariffs, raising costs for their producers and consumers while driving a wedge between trade relationships. This creates direct costs and increases economic and political uncertainty — something businesses dread when planning for the future. Although tariffs don’t directly cause inflation — an issue controlled by the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy — they raise prices on specific goods through the added tax. These increased costs can ripple through the supply chain, affecting many products. International trade is complex, and protectionist measures like tariffs only exacerbate the complexities, worsening the situation.

The current account deficit with other countries is balanced by a capital account surplus, where foreign savings flow into the US, helping finance our national debt and keeping interest rates lower than they would otherwise be. However, the flow of funds is slowing as some countries shift away from the US dollar, opting for gold and other assets. This trend poses a risk to the US economy by potentially restricting our ability to trade with other countries and raising the cost of borrowing as interest rates rise. This shift from the dollar, known as de-dollarization, underscores the importance of maintaining strong international trade relationships and avoiding protectionist policies alienating trading partners. As global confidence in the US dollar wanes, the economic benefits of foreign investment could diminish, leading to higher costs for Americans.

Tariffs Worsen Broader Problems at Home

As noted above, the broader economic problems facing the US stem from high taxes, overregulation, and government policies that make it more expensive for businesses to operate. Tariffs worsen these problems by raising costs for American businesses and consumers. By taxing imports, tariffs increase the prices of goods that US producers need to remain competitive. This adds to the burdens already imposed by high taxes and government mandates, effectively taxing Americans twice — once through tariffs and again through the costs of domestic overregulation.

Rather than addressing the domestic policy environment that has hindered US competitiveness for decades, tariffs only complicate matters. US companies struggle with excessively high corporate taxes, incentivizing them to move operations overseas. Before the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, the US had the highest corporate tax rate in the developed world. While the Act lowered the federal corporate tax rate to 21 percent, proposals to raise it to 28 percent would once again make US companies less competitive globally.

Like Texas, right-to-work states in the South have demonstrated how pro-growth policies can attract manufacturing jobs by creating a business-friendly environment. These states have attracted jobs lost from the Rust Belt by fostering lower taxes and fewer regulations. On the other hand, tariffs stifle economic growth by driving up costs, making it harder for these states to sustain their competitive advantage.

In sum, tariffs don’t solve American businesses’ real issues — they make them worse. Instead of protectionist measures, the US needs to focus on reducing domestic costs by lowering taxes, cutting red tape, and fostering an environment that encourages innovation and growth.

Protectionism: A Failed Policy

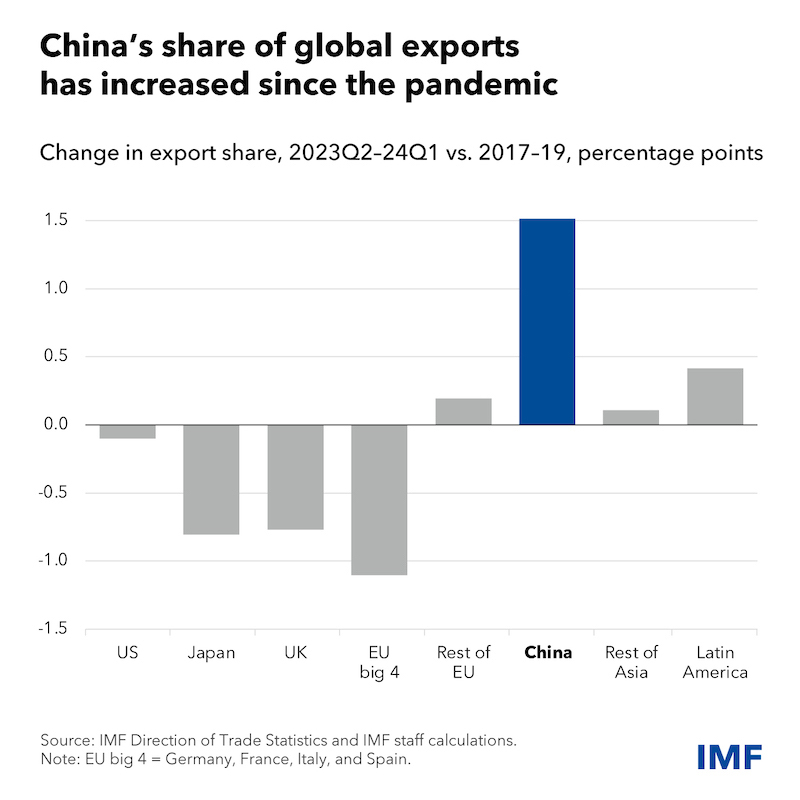

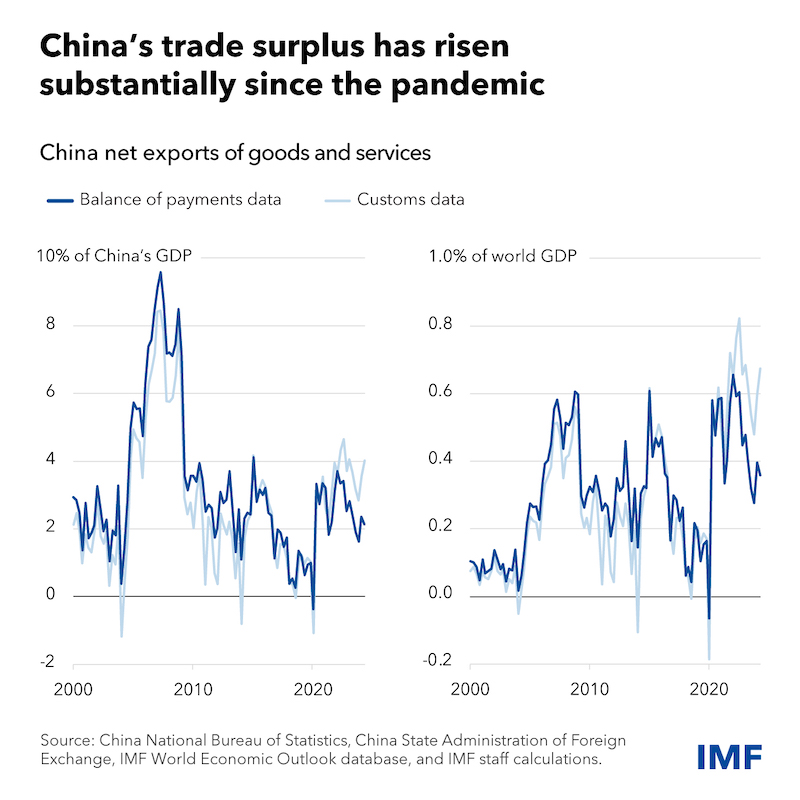

The economic data between 2016 and 2021 highlight the failure of protectionist policies, including raising tariffs that began in 2017.

Consider that global manufacturing output was $14.1 trillion in 2016, with China leading at $4 trillion and the US following at $2.3 trillion. In 2021, it rose to $16 trillion, with China’s part increasing to $4.9 trillion and the US’s to $2.5 trillion. Global manufacturing output grew by 13.5 percent. While China’s manufacturing surged by 22.5 percent, the US had a more modest increase of 8.7 percent. Of course, this period had significant initial and retaliatory tariffs between these countries and lockdowns in response to a global pandemic.

Since 2017, the Trump and Biden administrations have imposed $79 billion in tariffs as part of protectionist policies meant to shield domestic industries. Despite these efforts, global manufacturing continued to grow, and the economic pie expanded — but China captured a larger slice, increasing its share from 28.3 percent to 30 percent. The US trade deficit with China continued to widen, undermining the asserted goal of protectionism. Meanwhile, US manufacturers struggle with higher production costs, passed down to American consumers through increased prices on specific goods.

The Case for Free Trade

The US should abandon protectionism and embrace free trade policies that foster innovation, improve efficiency, and lower costs for consumers and businesses. When countries engage in free trade, all parties benefit from the specialization of labor and resources. Protectionist measures like tariffs distort markets, raise costs, and create uncertainty, hurting American consumers and producers.

Free trade doesn’t mean ignoring unfair trade practices by bad actors like China. However, the best way to address these challenges is not through blanket tariffs but by expanding trade with allies and non-hostile nations. For example, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)offered an opportunity to strengthen economic ties with 12 countries, pressuring China to play by the rules or risk losing access to major markets. Unfortunately, withdrawing from the TPP in 2017 was a missed opportunity to enhance American competitiveness while holding China accountable.

Conclusion

Tariffs are not the right tool to address the challenges facing American industries. They are a tax on imports, raising costs for consumers and producers while failing to tackle the real issues at home: excessive government spending, high taxes, overregulation, and outdated domestic policies hinder US competitiveness. By embracing free-market solutions — eliminating tariffs, reducing spending, reforming taxes, and cutting regulations — the US can create an environment where American businesses can thrive without relying on harmful protectionist measures. The path forward lies in pro-growth free trade efforts — unilaterally or through agreements with other countries — and domestic reforms, not in tariffs that hurt those they aim to protect.

- About the author: Vance Ginn, Ph.D., is founder and president of Ginn Economic Consulting, LLC and an Associate Research Fellow with AIER. He is chief economist at Pelican Institute for Public Policy and senior fellow at Americans for Tax Reform. He previously served as the associate director for economic policy of the White House’s Office of Management and Budget, 2019-20.

- Source: This article was published at AIER

AIER

The American Institute for Economic Research educates people on the value of personal freedom, free enterprise, property rights, limited government, and sound money. AIER’s ongoing scientific research demonstrates the importance of these principles in advancing peace, prosperity, and human progress. AIER is a nonpartisan research and education nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization focused on the importance of markets, with a full range of programs and publications on the social sciences with a primary emphasis on economics.