[By Xie Rouhan]

The world’s population is due to reach 9.7 billion by 2050 and sustainable approaches to feeding the extra mouths are crucial. The fishing sector will play a vital role according to an influential report by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

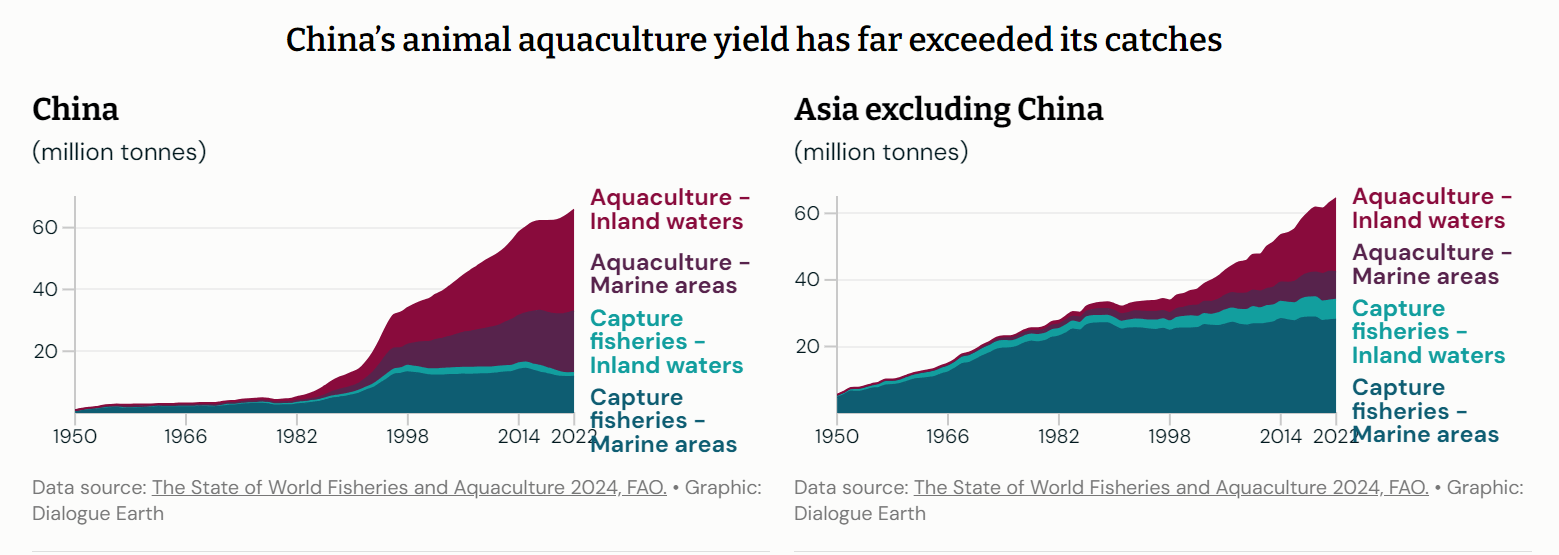

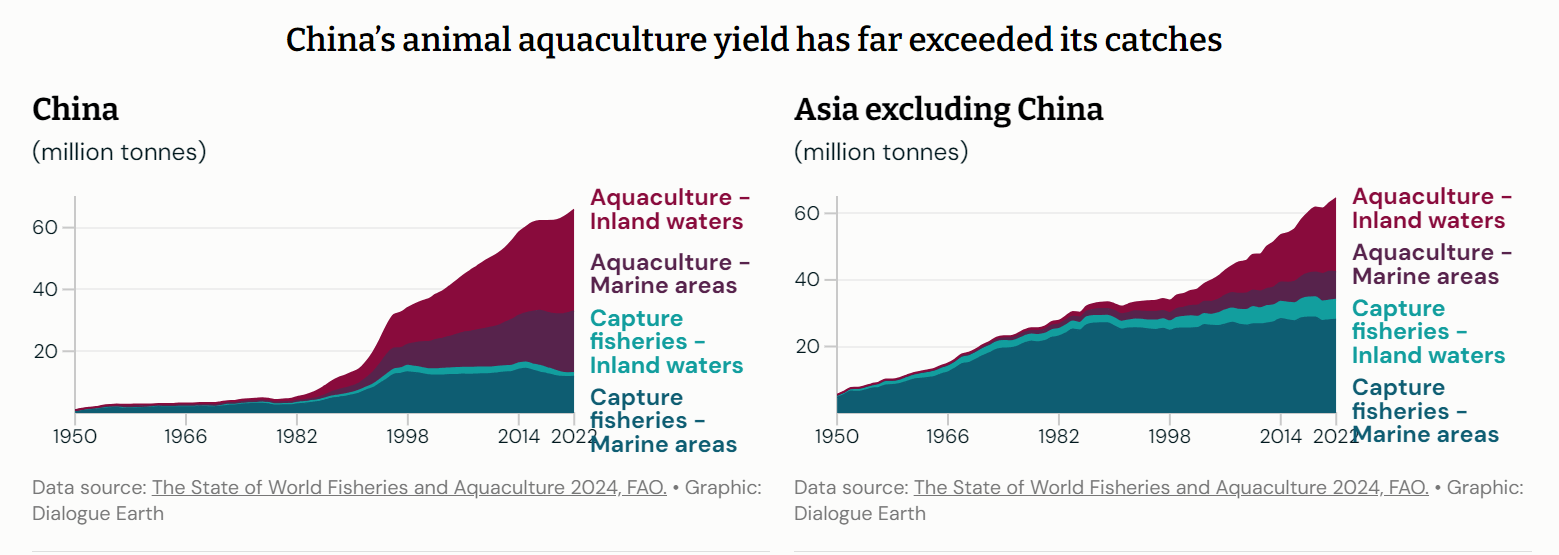

In 2022, production reached a record high, driven by a surge in animal aquaculture that exceeded wild catch for the first time, found the latest State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture report.

China has played a significant role in this transition. It has been the largest source of fish production since about 1989, for both marine wild catch and aquaculture. By 2022, China accounted for nearly 40% of global output.

But its marine catch declined from 14.4 million tonnes in 2015 to 11.8 million tonnes in 2022, a fall of nearly 18%, the FAO report noted. Meanwhile, with more than a decade of development behind it, China has become the main driver of growth in aquaculture production, not just in Asia, but globally.

Addressing coastal fish depletion through aquaculture

The dwindling fish stocks caused by decades of overfishing have pushed China to expand its aquaculture.

China has more fishing vessels than any other nation, with many operating in home waters and overexploiting coastal fishery resources. Ocean warming and acidification due to climate change pose a further threat to China’s nearshore fish populations, including those of the large yellow croaker, sea bream and sandlance.

Tackling the depletion has been at the core of China’s fisheries policy for two decades, with the focus being on reducing wild catch. In 2003, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs issued guidelines for reducing the number and capacity of fishing vessels. The ministry subsequently introduced seasonal fishing moratoriums, which have since been extended in both duration and area covered. In 2017, coastal provinces began testing and rolling out quota systems, limiting the netting of designated fish stocks within specific zones.

Challenges for distant-water fisheries

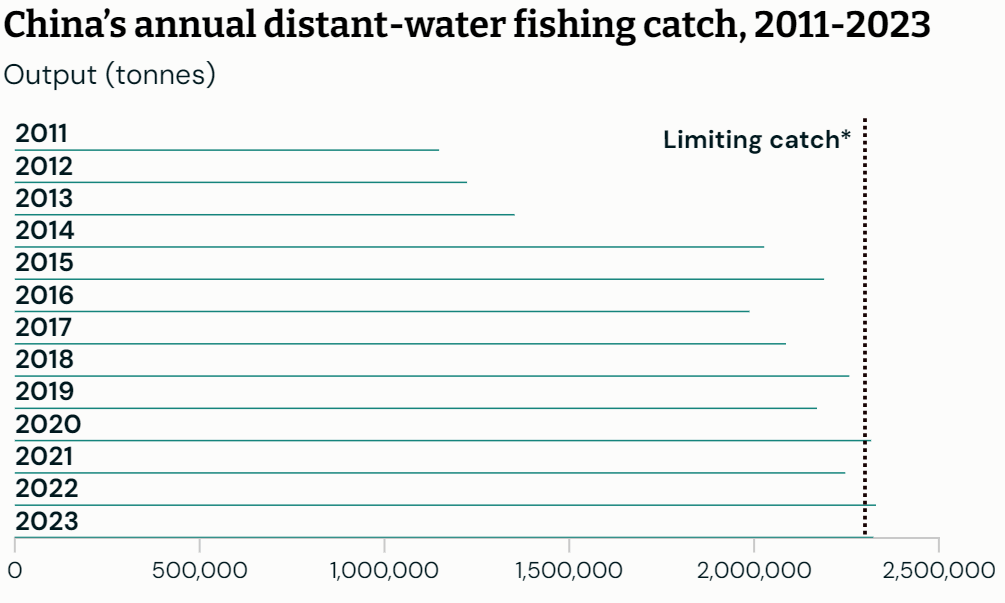

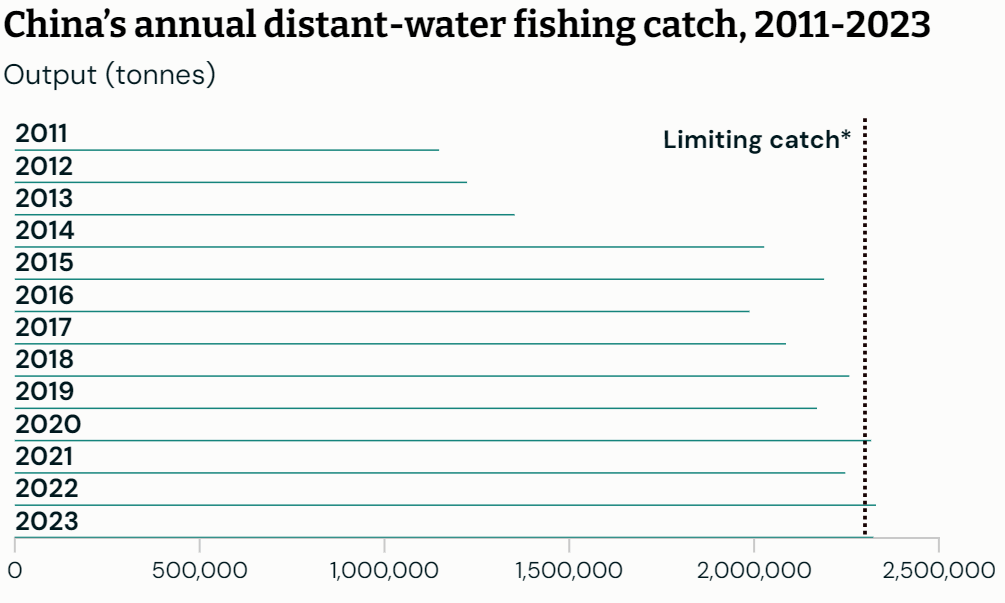

To compensate for the declining domestic catches, China has also expanded its distant-water fishing (DWF) operations since 2000. Production in 2022 was 2.33 million tonnes, up by nearly 4% year-on-year and accounting for almost 18% of national wild catch, according to the China Fishery Statistical Yearbook.

The growth of DWF is controversial internationally, leading to mounting concerns about sustainability and transparency. China’s large-scale operations in West Africa, for example, compete for local fish stocks and affect livelihoods, though other nations are also involved in this region and others.

Some of these operations’ involvement in illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing has drawn the Chinese government to respond with a blacklisting system and other tools for cracking down.

By 2016, China had nearly 2,900 DWF vessels including those under construction, with the number in operation having increased by 66% since 2010, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs data showed. By 2022, the figure had dropped to 2,551 according to China’s white paper on development of distant-water fisheries.

China has been restricting its DWF operations since 2020. The policy includes self-imposed moratoriums on fishing in international waters and limits on the number of squid boats active in certain areas.

The policy of “developing sustainable distant-water fisheries” was first introduced in the country’s 14th Five Year Plan for 2021-2025. In 2022, the government set a target of limiting DWF catch to around 2.3 million tonnes by 2025, aiming to curb the industry’s expansion and drive “high-quality development”.

With declining marine catch and constraints on distant-water fishing, China began looking to aquaculture to ensure future food security. Its aquacultural output was already four times that of capture fishing by the end of 2020, the last year of the 13th Five Year Plan. The importance of developing the sector was further asserted in the plan that followed.

China’s transition to aquaculture

China is a significant driver of aquaculture worldwide. In 2022, 83.4 million tonnes of aquatic animals were harvested in Asia, up from 77.5 million tonnes two years before. China accounted for 55.4% of this growth, adding 3.3 million tonnes of animal aquaculture between 2022 and 2020, according to the FAO.

The rapid and sometimes haphazard development of aquaculture has brought challenges, including coastal-water pollution from fish farms and uncontrolled use of fishery drugs.

Zhou Wei, head of the oceans programme at Greenpeace East Asia, told Dialogue Earth: “Farming certain carnivorous fish, shrimps and crabs requires large amounts of feed made from wild juvenile fish, which puts wild stocks under pressure. There are concerns about the sustainability of this kind of model.”

China began promoting green aquaculture technologies in 2021 to make the fish-farming industry more sustainable. The measures include controlling wastewater discharge, reducing drug use, and mixing juvenile fish with land-harvested ingredients to create “compound feed”.

In the same year, the government finalised aquaculture planning nationwide to mitigate adverse environmental impacts. As part of this planning work, local and national authorities designated certain zones for general aquaculture, others for “restricted aquaculture” with stricter environmental standards, and others where aquaculture is banned.

However, gaps remain between policy and practice. Zhou says insufficient supporting personnel and skills have held back policy implementation.

She adds there are nearly 200,000 vessels active in China’s coastal fisheries, which employ tens of millions of people. It is an enormous, complex industry with manifold regional differences.

The lack of management capacity and skilled personnel has hindered policy implementation, from expanding research and innovation, to providing alternative employment for fishers.

A major exporter, with imports on the rise

China’s fishery products contribute hugely to global food production, and it remained the world’s largest exporter of such products in 2022, according to the FAO report. Japan, the US and South Korea are its main export destinations, with cuttlefish, squid and cod making up the bulk of those exports.

But its imports have also grown significantly. The report shows that in 2022 China became a net importer of aquatic animal products by value. (In volume terms, it has been a net importer of them since the mid 1980s, with the trade deficit widening in recent years.)

Ecuador, Russia and Vietnam supplied the largest share of those imports. Shrimp, Atlantic cod, lobsters and crabs predominate but feed for livestock and feedstock for the seafood-processing sector are also imported.

The report says this reflects China’s growing demand for foreign products and the outsourced processing work it does on aquatic products from other countries.

These are precisely the trends illustrated by the China Fisheries Association in a 2021 analysis stating that the supply of aquatic products in China “will come to further rely on aquaculture and imports”.

Aquaculture will also become increasingly important globally, with the FAO expecting it to account for 54% of world output of aquatic animals by 2032 – three percentage points higher than in 2022. The transition is set to continue.

Xie Ruohan is founder of the pan-cultural Chinese podcast Anachronism. She holds a master’s degree in political communications from the University of Amsterdam, and has written on issues including climate justice and immigration for Chinese and international media.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.

Courtesy NTSB

Courtesy NTSB Ruby with its cargo of ammonium nitrate would pass through the shipping channel under the Great Belt Bridge in Denmark (L-BBE -- CC BY 3.0 Deed)

Ruby with its cargo of ammonium nitrate would pass through the shipping channel under the Great Belt Bridge in Denmark (L-BBE -- CC BY 3.0 Deed)