On the transformation of social property relations under China’s party-state regime

In a previous article, we analysed the relationship between the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the Chinese bourgeoisie, and the consequences of this in terms of the class character of the ruling bureaucracy. We demonstrated how the Stalinist bureaucracy has become increasingly fused with sections of the new capitalist class.1 In this article, we will show how China’s transformation from a Stalinist degenerated workers' state into a capitalist state — which took place under CPC rule — can be explained within the framework of the Marxist theory of the state. This is important as many Marxists are confused by the fact that the same political regime oversaw one mode of production and then facilitated its transformation into another. We will show that this is not only possible but that China is by no means a unique example.

The CPC in the process of revolution and counter-revolution

The CPC was founded as a revolutionary organisation in 1921. While small at the beginning, it grew rapidly in the Second Chinese Revolution (1925-27), developing important links with the working class and poor peasantry. However, the Kremlin imposed on the party a political strategy of subordination to the bourgeois Kuomintang party, which left the CPC unprepared to deal with Chiang Kai-shek’s bloody counterrevolution against it and the vanguard of the working class in 1927.

After defeat in 1927, the now Stalinist CPC became totally bureaucratised, lost most of its links to the urban proletariat, and retreated to the countryside. It transformed into a party composed mostly of peasants. According to Peng Shu-Tse, a CPC leader who was expelled for his Trotskyist views, workers made up less than 1% of the party’s membership in the early ’30s. The party went on to organise a rural guerilla struggle against the Kuomintang party and played a leading role in the resistance to the Japanese invasion. Through all those years, it remained closely aligned to the Stalinist bureaucracy of the Soviet Union.2

After the defeat of Japanese imperialism at the end of World War II, the CPC successfully overthrew the Kuomintang regime in 1949 (which was forced to retreat to Taiwan). Initially, the CPC leadership under Mao Zedong tried to build a Stalinist utopia, dubbed a “New Democracy”, together with the capitalists. This project collapsed, however, due to pressure from the masses who wanted to go further, sabotage by landowners and capitalists, and the Cold War with the US. This forced the Mao leadership — against its original intentions — to carry out a social revolution, abolish capitalist relations of production and establish a workers state based on a nationalised and planned economy.

But this transformation was carried out through bureaucratic methods and brutal oppression against rebellious workers and peasants (including supporters of the Revolutionary Communist Party, the Chinese section of the Fourth International). From the very beginning, the new workers state was bureaucratically degenerated and the working class politically expropriated.3

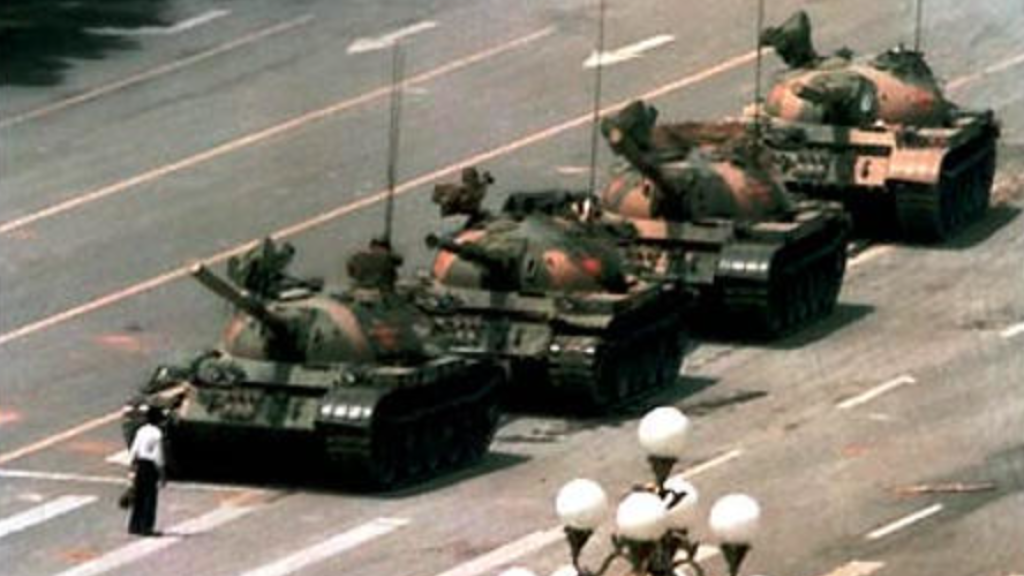

The following decades saw social and economic progress, as well as vicious faction struggles within the bureaucracy. The country was shattered by devastating campaigns such as the “Great Leap Forward” (1958-62), which led to a horrible famine and millions of deaths, and the “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution” (1966-76). From 1978, the CPC — now led by the group around Deng Xiaoping — introduced a number of market reforms that enabled economic growth but accelerated political and social contradictions. These tensions ultimately provoked a workers and student uprising in April-June 1989, which was brutally smashed by the CPC bureaucracy.

In the following years, the party leadership drew up a balance sheet of these events that also took stock of lessons from the collapse of Stalinist rule in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. As a result, the bureaucracy opted, on one hand, to accelerate market reforms and restore capitalism while, on the other hand, maintained its absolute political monopoly through the one-party dictatorship. The starting point of this new course was Deng’s famous Southern Tour in 1992. These developments resulted in the emergence of a new capitalist class and China’s transformation into a new imperialist power.4

All these developments were formally undertaken by the same party dictatorship. So, how can this be explained from the point of view of Marxist theory?

The character and role of the state in Marxist theory

To understand the contradictory role of the Stalinist regime in China, we need to return to Marxist teachings about the character and the role of the state. The state is essentially a product of social contradictions within a society. It emerged with the division of the society into owners and non-owners of means of production. Rising from class divisions in society, the state necessarily places itself above society and becomes an institution that is both organically linked with and, at the same time, antagonistically opposed to society.

Friedrich Engels noted:

The state is, therefore, by no means a power forced on society from without; just as little is it “the reality of the ethical idea”, “the image and reality of reason”, as Hegel maintains. Rather, it is a product of society at a certain stage of development; it is the admission that this society has become entangled in an insoluble contradiction with itself, that it has split into irreconcilable antagonisms which it is powerless to dispel. But in order that these antagonisms, classes with conflicting economic interests, might not consume themselves and society in fruitless struggle, it became necessary to have a power seemingly standing above society that would alleviate the conflict and keep it within the bounds of “order”; and this power, arisen out of society but placing itself above it, and alienating itself more and more from it, is the state.5

Vladimir Lenin, in the same spirit, said in his 1919 lecture on the state:

History shows that the state as a special apparatus for coercing people arose wherever and whenever there appeared a division of society into classes, that is, a division into groups of people some of which were permanently in a position to appropriate the labour of others, where some people exploited others.6

Furthermore, the state is not an instrument of society but rather an instrument of the ruling class to suppress the lower classes and control and administer society in its interests. The state must, therefore, necessarily possess various means of coercion. In their famous Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx and Engels stated: “The executive of the modern State is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.”7 Lenin noted in State and Revolution: “The state is a special organisation of force: it is an organisation of violence for the suppression of some class.”8

The state is organically linked to the class society it resides above. What does this mean? It means that the character of the state usually reflects the character of the economic fundament of said society. While there can be periods — albeit only temporary — where the character of the economy and the state are not identical, in general they share the same nature. The reason for this is obvious: the class of property owners is the ruling class, hence it usually also dominates the political sphere of society; that is, the state apparatus.

This takes us to the next important conclusion in determining the nature of the exploiter state: the class character of the state — slave-holder, oriental despotic, feudal, capitalist, etc — is derived from the specific class character of the economy. China’s Empire — under the Tang dynasty, Yuan or Ming dynasty — was not dominated by a class of slave holders, since slavery did not play a large role in the economic process of production and reproduction. Rather, it was a class dominating a despotic state machine based on the revenue extracted from the surplus labour of peasants working on private or state land. Likewise, European states in the Middle Ages were dominated by the class that possessed land — the feudal aristocracy.

Marx emphasised this point on numerous occasions. For example, in Capital Vol. III he wrote:

The specific economic form, in which unpaid surplus labour is pumped out of direct producers, determines the relationship of rulers and ruled, as it grows directly out of production itself and, in turn, reacts upon it as a determining element. Upon this, however, is founded the entire formation of the economic community which grows up out of the production relations themselves, thereby simultaneously its specific political form. It is always the direct relationship of the owners of the conditions of production to the direct producers – a relation always naturally corresponding to a definite stage in the development of the methods of labour and thereby its social productivity – which reveals the innermost secret, the hidden basis of the entire social structure, and with it the political form of the relation of sovereignty and dependence, in short, the corresponding specific form of the state.9

The state in general, state forms and the ‘bureaucratic-military state machine’

At this point, it is crucial to clarify the category “state” and be aware of its different meanings.10 Marxists (and non-Marxists) often use this category to signify the whole social formation; that is, the political superstructure, as well as the means of production and social classes that live within a definite territory. For example, when we speak of the Roman Empire as a slaveholder state, or France as a “capitalist state” or the USSR as a “degenerated workers’ state”, we have the totality of the socio-economic formation in mind. But in this essay, we are speaking specifically about the class character of the state in general (or the state type).

When we use the term state in this way and seek to define its fundamental class character, we do so according to the property relations that predominate and are protected by the political superstructure, no matter what class character this specific superstructure might have if analysed in isolation from this economic base. The USSR under Stalin, for example, remained a workers’ state despite the monstrous totalitarian character of its apparatus of repression.

However, when we speak about the state as an institution separated from the economy and “civil society”, we mean the specific political superstructure; that is, the state apparatus. Such a political superstructure can take various forms: from dictatorship to democracy, from monarchy to republic. Here, we are speaking about the class character of the state form, understanding that one and the same type of state can take different state forms. The slaveholder state in Greece or Rome, for example, had different forms of regimes: democracy, republic, monarchy. Likewise, a capitalist state can be bourgeois-democratic, bonapartist, fascist, military dictatorship, etc.

Different forms, however important they may be, are not “the essence” of the state. Even the most representative of these institutions, subject to periodic elections under a system of universal suffrage, come and go without anything fundamentally changing about the essence of the “state”. This is because the core of such a state apparatus is its means of coercion to oppress the lower classes. In modern history, this means the repression apparatus (police, standing army, justice) and the state bureaucracy. This constitutes the essence of what Marx and Lenin called the “bureaucratic-military state machine” — a machine which every working-class revolution must smash. As Marx wrote:

If you look up the last chapter of my Eighteenth Brumaire, you will find that I declare that the next attempt of the French Revolution will be no longer, as before, to transfer the bureaucratic-military machine from one hand to another, but to smash it, and this is the precondition for every real people's revolution on the Continent.11

During the course of the historic process of social development, the role of the state has become more important as societies have become larger, the division of labour more complex, the relations between the classes more and more entangled and, as a result, contradictions have become sharper and explosive. Hence, the bureaucratic-military state machine core has become more hypertrophied and powerful vis-a-vis other components of the state.

Political superstructure and economic basis

However, it would be mistaken to imagine that the character of the political superstructure and economic basis are always completely identical. One of the most important laws of history, as Leon Trotsky explained, is uneven and combined development. This basically means that different historical developments in societies with different social characteristics influence and shape each other.12 A particularly important factor for such unevenness is the struggle between classes since, as Marx and Engels emphasised in the Communist Manifesto, the history of all class societies is a history of class struggle.

It is important to recognise that temporary contradictions between the character of the political superstructure and the economic basis can exist, and have repeatedly done so in history (more on this below). Likewise, history has seen various cases where the economy was characterised not by one but by two or more different relations of productions. The late Roman Empire of the 3rd to the 5th century, or the Byzantine Empire of the 6th to the 9th century, saw the parallel existence of ancient and early feudal forms of property. Europe in the 16th to 19th century and, later, numerous countries in Latin America, Asia and Africa saw the parallel, and often combined, existence of feudal, semi-feudal and capitalist property forms. As a result, the ruling class could have a contradictory and combined character in such cases.

Likewise, the political superstructure can have a mixed character, combining semi-feudal as well as bourgeois elements, for example. This is particularly possible in periods of transition between two different socio-economic formations. In short, the relationship between the economic basis and political superstructure knows all forms of dialectical contradictions and forms of transition and shades.

On the relative autonomy of the state

Bourgeois critics have accused Marxism of preaching a simplistic schema of one-sided determinism, according to which the economic basis determines everything and the superstructure is merely a passive reflection of the former. While it is true that some Marxists have supported such ideas, neither Marx and Engels, nor Lenin, Luxemburg and Trotsky ever shared such conceptions. They emphasised that the superstructure, including the state, is of course determined by the economic basis, but only in the last instance. At the same time, they explained that the different parts possess a relative autonomy within the totality of a given social formation.

In a letter to Joseph Bloch in 1890, Engels wrote:

According to the materialistic conception of history, the production and reproduction of real life constitutes in the last instance the determining factor of history. Neither Marx nor I ever maintained more. Now when someone comes along and distorts this to mean that the economic factor is the sole determining factor, he is converting the former proposition into a meaningless, abstract and absurd phrase. The economic situation is the basis but the various factors of the superstructure – the political forms of the class struggles and its results – constitutions, etc., established by victorious classes after hard-won battles – legal forms, and even the reflexes of all these real struggles in the brain of the participants, political, jural, philosophical theories, religious conceptions and their further development into systematic dogmas – all these exercise an influence upon the course of historical struggles, and in many cases determine for the most part their form. There is a reciprocity between all these factors in which, finally, through the endless array of contingencies (i.e., of things and events whose inner connection with one another is so remote, or so incapable of proof, that we may neglect it, regarding it as nonexistent) the economic movement asserts itself as necessary. Were this not the case, the application of the history to any given historical period would be easier than the solution of a simple equation of the first degree. We ourselves make our own history, but, first of all, under very definite presuppositions and conditions. Among these are the economic, which are finally decisive. But there are also the political, etc.13

Such relative autonomy is based on the fact that: the ruling class is usually divided into different factions; it is under pressure from ruling classes of rivalling states; and it is under pressure from the oppressed classes — or class struggle from below.

In summary, we can say that the exploiter state is a machinery that historically evolved at a certain stage of development of human society in connection with the emergence of classes. It is a centralised instrument of the ruling class — a machinery of coercion, bureaucratic administration and manipulation — guaranteeing the exploitation of surplus labour of the oppressed classes. The type of state changes with the nature of the dominant mode of production; namely, the kind of property relations which a given state defends. There can be various state forms within a given type of state. However, the relationship between the political superstructure and economic basis is not necessarily identical and can be contradictory and uneven — at least for certain periods.

Stalinism and character of the state apparatus in a degenerated workers’ state

When the Russian masses took power in October 1917, they created the first workers’ state in history. Led by the Bolshevik party, this new state was based on workers, peasants and soldiers’ councils. These institutions regularly met and elected delegates who were recallable. Such a pyramid-shaped system from below to the top ensured the democratic participation of the masses.

This Soviet-type state broke up the old bureaucratic-military state machine of the exploiter state and smashed the police, standing army and bureaucracy. Instead, officials were elected from below and could be recalled at any time. No official received a higher wage than a skilled worker. The police and standing army were replaced by armed red guards (and, later, a new Red Army).

Comparing such a type of state with the Paris Commune — the first attempt of the working class to create its own state power — Lenin wrote in 1917:

The fundamental characteristics of this type are: (1) the source of power is not a law previously discussed and enacted by parliament, but the direct initiative of the people from below, in their local areas — direct “seizure”, to use a current expression; (2) the replacement of the police and the army, which are institutions divorced from the people and set against the people, by the direct arming of the whole people; order in the state under such a power is maintained by the armed workers and peasants themselves, by the armed people themselves; (3) officialdom, the bureaucracy, are either similarly replaced by the direct rule of the people themselves or at least placed under special control; they not only become elected officials, but are also subject to recall at the people’s first demand; they are reduced to the position of simple agents; from a privileged group holding “jobs” remunerated on a high, bourgeois scale, they become workers of a special “arm of the service”, whose remuneration does not exceed the ordinary pay of a competent worker. This, and this alone, constitutes the essence of the Paris Commune as a special type of state.14

The new workers’ state, based on the support of the masses, managed to overcome the vicious counterrevolutionary forces, including both the coalition of monarchists, bourgeois “democrats” and reformists and the invading forces of 16 foreign armies, between 1917-21. However, the workers’ state remained isolated, mainly due to the combined efforts of imperialist powers to contain the revolutionary wave but also the lack of experience of the new Communist Parties in Europe.

As a result, the Soviet Union — where a new socialist economy and social order had to be built on the basis of a backward semi-feudal and bourgeois society — faced increasing difficulties, which contributed to the start of a process of bureaucratisation. To counter such a development, Trotsky and the Left Opposition proposed a focus on the internationalisation of the revolution, the revitalisation of party and soviet democracy, and the creation of a planned economy with an expanding industrial base. However, the majority of the party leadership rejected such a strategy and increasingly merged with the new bureaucracy. By 1927, the Left Opposition was expelled from the party and thousands of authentic Communists were imprisoned and later killed.15

Trotsky and his supporters called this process the “Thermidor” of the October Revolution, where Soviet democracy was destroyed and the working class politically expropriated. The Stalinist bureaucracy created an absolutist and bonapartist dictatorship, which brutally suppressed the masses. At the same time, it could not abolish the socio-economic foundation of the workers’ state (nationalisation of the key sectors of the economy, foreign trade monopoly, planning) on which its power — and privileges — rested.

The contradictory nature of the Stalinist bureaucracy in a degenerated workers’ state

It is clear that such a state was a highly contradictory phenomenon. It was neither a healthy workers state nor a capitalist state. Trotsky called it a degenerated workers’ state: a state dominated by a petty-bourgeois bureaucracy whose power rested economically on post-capitalist, proletarian property relations and politically on a bourgeois-bureaucratic state machinery.16

Was the Stalinist bureaucracy a new class? Trotsky insisted that the answer was no. The bureaucracy was not a class but rather a caste. It did not, as a class does, own the means of production, since the bureaucracy ruled on the basis of proletarian, and not capitalist, relations of production. Under such proletarian relations of production, the law of value — the basis of capitalism — does not dominate the economy. In contrast to the capitalist class, the Stalinist bureaucracy is not an exploiting class that appropriates surplus value. It constitutes a caste that plays no necessary role in the running of the economy and the society as a whole; instead, it parasitically appropriates numerous privileges because of its commanding position in the state. Trotsky wrote:

Embezzlement and theft, the bureaucracy’s main sources of income, do not constitute a system of exploitation in the scientific sense of the term. But from the standpoint of the interests and position of the popular masses it is infinitely worse than any “organic” exploitation. The bureaucracy is not a possessing class, in the scientific sense of the term. But it contains within itself to a tenfold degree all the vices of a possessing class. It is precisely the absence of crystallized class relations and their very impossibility on the social foundation of the October revolution that invest the workings of the state machine with such a convulsive character. To perpetuate the systematic theft of the bureaucracy, its apparatus is compelled to resort to systematic acts of banditry. The sum total of all these things constitutes the system of Bonapartist gangsterism.17

From this it follows that the ruling bureaucracy in a degenerated workers’ state is neither part of the proletariat (which the bureaucracy oppresses and robs), nor does it constitute a capitalist class; rather, it possesses a petty-bourgeois character. Due to its parasitism and conservative, anti-revolutionary role — in terms of international and domestic policy — it serves the world bourgeoisie. However, as long as it stands at the top of a workers’ state and administers and defends proletarian property relations, the bureaucracy does not constitute a capitalist ruling class but rather a petty-bourgeois, counter-revolutionary caste, defending the workers’ state to safeguard its privileges.

That is why these Stalinist countries remained (degenerated) workers’ states despite their domination by an anti-proletarian bureaucratic caste. The class character of a state is defined by the economic base that a given political regime administers and defends. As Trotsky explained: the class nature of the state is, consequently, determined not by its political forms but by its social content; i.e., by the character of the forms of property and productive relations which the given state guards and defends..18

In making analogies, Trotsky compared the ruling bureaucracy in a Stalinist workers’ state with the bureaucracy of a trade union:

The class character of the state is determined by its relation to the forms of property in the means of production. The character of a workers’ organization such as a trade union is determined by its relation to the distribution of national income. The fact that Green and Company defend private property in the means of production characterizes them as bourgeois. Should these gentlemen in addition defend the income of the bourgeoisie from attacks on the part of the workers; should they conduct a struggle against strikes, against the raising of wages, against help to the unemployed; then we would have an organization of scabs, and not a trade union. However, Green and Company, in order not to lose their base, must within certain limits lead the struggle of the workers for an increase — or at least against a diminution — of their share of the national income.…

The function of Stalin, like the function of Green, has a dual character. Stalin serves the bureaucracy and thus the world bourgeoisie; but he cannot serve the bureaucracy without defending that social foundation which the bureaucracy exploits in its own interests. To that extent does Stalin defend nationalized property from imperialist attacks and from the too impatient and avaricious layers of the bureaucracy itself. However, he carries through this defense with methods that prepare the general destruction of Soviet society. It is exactly because of this that the Stalinist clique must be overthrown. The proletariat cannot subcontract this work to the imperialists. In spite of Stalin, the proletariat defends the USSR from imperialist attacks.…

The assertion that the bureaucracy of a workers’ state has a bourgeois character must appear not only unintelligible but completely senseless to people stamped with a formal cast of mind. However, chemically pure types of state never existed, and do not exist in general. The semifeudal Prussian monarchy executed the most important tasks of the bourgeoisie, but executed them in its own manner, i.e., in a feudal, not a Jacobin style. In Japan we observe even today an analogous correlation between the bourgeois character of the state and the semifeudal character of the ruling caste. But all this does not hinder us from clearly differentiating between a feudal and a bourgeois society. True, one can raise the objection that the collaboration of feudal and bourgeois forces is immeasurably more easily realized than the collaboration of bourgeois and proletarian forces, inasmuch as the first instance presents a case of two forms of class exploitation. This is completely correct. But a workers’ state does not create a new society in one day. Marx wrote that in the first period of a workers’ state the bourgeois norms of distribution are still preserved.… One has to weigh well and think this thought out to the end. The workers’ state itself, as a state, is necessary exactly because the bourgeois norms of distribution still remain in force.

This means that even the most revolutionary bureaucracy is to a certain degree a bourgeois organ in the workers’ state. Of course, the degree of this bourgeoisification and the general tendency of development bear decisive significance. If the workers’ state loses its bureaucratization and gradually falls away, this means that its development marches along the road to socialism. On the contrary, if the bureaucracy becomes ever more powerful, authoritative, privileged, and conservative, this means that in the workers’ state the bourgeois tendencies grow at the expense of the socialist; in other words, that inner contradiction which to a certain degree is lodged in the workers’ state from the first days of its rise does not diminish, as the “norm” demands, but increases. However, so long as that contradiction has not passed from the sphere of distribution into the sphere of production, and has not blown up nationalized property and planned economy, the state remains a workers’ state.19

Degenerated workers’ states were characterised by a contradiction that has confused many Marxists. The working class was socially and economically the ruling class but, at the same time, it was politically oppressed by the bureaucracy. While this might look strange to people who do not go beyond mechanic thinking, such a situation is in fact not unique in history. In the late period of Tsarist Russia, the capitalist class dominated the country’s economy. However, they did not participate in the political leadership of the country, as it was run by the imperial dynasty and nobility. (This issue, by the way, was also debated between Trotsky and Marxist historian M. N. Pokrovsky in the 1920s.20) We saw similar developments in other long-standing feudal empires.

Stalinism’s bourgeois-bureaucratic and Bonapartist state machine

Evidently, a fundamental antagonism exists between the economic base of the workers’ state — the proletarian relations of production — and its anti-proletarian, petty-bourgeois bureaucracy, which rules the political superstructure of this state. The political conquests of the October Revolution — workers’ democracy based on Soviets, a state apparatus under control of the masses, officials without vast privileges, no standing army – had been smashed by the Stalinist bureaucracy.

To maintain its rule, the Stalinist bureaucracy needed a state apparatus immune from control by the working class and popular masses, and that could be utilised against the masses to defend the bureaucracy’s privileges. Such a state apparatus, totally alienated from the working class, therefore had a bourgeois character. In other words, Stalinism implemented a political counterrevolution in the 1920s and ’30s, replacing the “proletarian semi-state” (Lenin) with an anti-proletarian, bourgeoisified state machine. Trotsky called this process a pre-emptive civil war of the Stalinists against the workers’ vanguard.

When Le Temps, the leading paper of the French bourgeoisie, commented that the reinstitution of symbols of ranks in the Red Army reflected a wider process in the Soviet Union and concluded “The Soviets are getting more and more bourgeois”, Trotsky wrote:

We encounter such statements by the thousand. They incontrovertibly demonstrate that the process of bourgeois degeneration among the leaders of Soviet society has gone a long way. At the same time they show that the further development of Soviet society is unthinkable without freeing that society’s socialist base from its bourgeois-bureaucratic and Bonapartist superstructure.21

Trotsky explained that such class contradictions between the economy and the state are not only possible but had existed several times in history. In a debate with James Burnham and Joseph Carter, two leaders of the Socialist Workers Party (US), Trotsky wrote in 1937:

But does not history really know of cases of class conflict between the economy and the state? It does! After the “third estate” seized power, society for a period of several years still remained feudal. In the first months of Soviet rule the proletariat reigned on the basis of a bourgeois economy. In the field of agriculture the dictatorship of the proletariat operated for a number of years on the basis of a petty-bourgeois economy (to a considerable degree it does so even now).22

There are several other examples. During the epoch of early capitalism, a bourgeoisie, which established capitalist property relations in large sectors of the economy, coexisted with a feudal and absolutist monarchy and its state apparatus in many European countries. Likewise, the Roman Empire, which was based on a slaveholder economy, did not try to impose their relations of production on several new provinces it conquered in Western Asia and was content with collecting tribute. Another example is the state of the Yuan dynasty in China (1271–1368), which was a highly contradictory combination of traditional Chinese Han society, with elements of an Asiatic mode of production and feudalism, on one hand, and the political-military superstructure of the Mongolian conquerors, with its primitive militarised state form of organisation as a steppe people, on the other.

The Stalinist bureaucracy in the face of revolution and counterrevolution

Debates over appropriate categories for the Stalinist state were not an abstract discussion. They had profound consequences for the perspectives and tasks of the proletarian liberation struggle. If the Stalinists had smashed the “proletarian semi-state” and replaced it with an anti-proletarian, bourgeoisified state machine, the task of the working class was not to hope for peaceful reform of this machine but rather to orientate towards an armed insurrection against the bureaucracy — a political revolution.

In the Transitional Program — the founding document of the Fourth International — Trotsky wrote that “the chief political task in the USSR still remains the overthrow of this same Thermidorian bureaucracy.”23 Such an overthrow was the only way to open the road to socialism: “Only the victorious revolutionary uprising of the oppressed masses can revive the Soviet regime and guarantee its further development toward socialism.” To prepare for this task, Marxists had to build a new revolutionary party under illegal conditions.

Trotsky elaborated the tasks of the political revolution in his major work on Stalinism, The Revolution Betrayed:

In order to better understand the character of the present Soviet Union, let us make two different hypotheses about its future. Let us assume first that the Soviet bureaucracy is overthrown by a revolutionary party having all the attributes of the old Bolshevism, enriched moreover by the world experience of the recent period. Such a party would begin with the restoration of democracy in the trade unions and the Soviets. It would be able to, and would have to, restore freedom of Soviet parties. Together with the masses, and at their head, it would carry out a ruthless purgation of the state apparatus. It would abolish ranks and decorations, all kinds of privileges, and would limit inequality in the payment of labor to the life necessities of the economy and the state apparatus. It would give the youth a free opportunity to think independently, learn, criticize and grow. It would introduce profound changes in the distribution of the national income in correspondence with the interests and will of the worker and peasant masses. But so far as concerns property relations, the new power would not have to resort to revolutionary measures. It would retain and further develop the experiment of planned economy. After the political revolution – that is, the deposing of the bureaucracy – the proletariat would have to introduce in the economy a series of very important reforms, but not another social revolution.24

While Trotsky did not formulate it explicitly, it is clear from his writings that he expected the working-class revolution against the Stalinist bureaucracy to be much more violent than a possible capitalist restoration overthrowing proletarian property relations. The reason for this is that the “bourgeois-bureaucratic” state machine (police, standing army, bureaucracy) is not a proletarian instrument, but one of the petty-bourgeois Stalinist bureaucracy, which is much closer to the bourgeoisie than the working class. Therefore, the political revolution required not the reform but the smashing of the Stalinist-Bonapartist state apparatus.25

In one of his final articles on the Stalinist bureaucracy, Trotsky wrote in 1939:

The Bonapartist apparatus of the state is thus an organ for defending the bureaucratic thieves and plunderers of national wealth.… To believe that this state is capable of peacefully “withering away” is to live in a world of theoretical delirium. The Bonapartist caste must be smashed, the Soviet state must be regenerated. Only then will the prospects of the withering away of the state open up..26

He foresaw that any serious working class attempt to topple the bureaucracy would be met with the brutal armed force of the Stalinist apparatus. That is what happened to the proletarian uprisings in Eastern Germany (1953), in Hungary (1956), in Czechoslovakia (1968), in Poland (1980/81), in Kosova (1981), and in China (1989). On the other hand, when capitalist restoration occurred in Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union and China, between 1989-92, this was met with hardly any violent resistance by any faction of the Stalinist bureaucracy. The only possible exception was the three-day operetta of a few drunken generals in Moscow in August 1991 and, given its pathetic character, tends to confirm our thesis.

At the same time, Trotsky considered the Stalinist caste — given the bourgeoisified character of the bureaucracy and its state machine — as closer to capitalism than socialism. He wrote in The Revolution Betrayed that capitalist restoration would find much more support among the Stalinist bureaucracy than a working-class political revolution:

If – to adopt a second hypothesis – a bourgeois party were to overthrow the ruling Soviet caste, it would find no small number of ready servants among the present bureaucrats, administrators, technicians, directors, party secretaries and privileged upper circles in general. A purgation of the state apparatus would, of course, be necessary in this case too. But a bourgeois restoration would probably have to clean out fewer people than a revolutionary party. The chief task of the new power would be to restore private property in the means of production.27

If not overthrown, Trotsky expected that the inherent tendency of the Stalinist bureaucracy to become a property-owning class would, at some point, break through and open the road to capitalist restoration:

Let us assume – to take a third variant – that neither a revolutionary nor a counterrevolutionary party seizes power. The bureaucracy continues at the head of the state. Even under these conditions social relations will not jell. We cannot count upon the bureaucracy peacefully and voluntarily renouncing itself on behalf of socialist equality. If at the present time, notwithstanding the too obvious inconveniences of such an operation, it has considered it possible to introduce ranks and decorations, it must inevitably in future stages seek support for itself in property relations. One may argue that the big bureaucrat cares little what are the prevailing forms of property, provided only they guarantee him the necessary income. This argument ignores not only the instability of the bureaucrat's own rights, but also the question of his descendants. The new cult of the family has not fallen out of the clouds. Privileges have only half their worth, if they cannot be transmitted to one's children. But the right of testament is inseparable from the right of property. It is not enough to be the director of a trust; it is necessary to be a stockholder. The victory of the bureaucracy in this decisive sphere would mean its conversion into a new possessing class. On the other hand, the victory of the proletariat over the bureaucracy would insure a revival of the socialist revolution. The third variant consequently brings us back to the two first, with which, in the interests of clarity and simplicity, we set out.28

This process took longer than Trotsky expected. World War II and the gigantic mass mobilisation in the Soviet Union to defend the country against Nazi-Germany; the revolutionary and counterrevolutionary developments after the war (particularly in Europe and Asia); the onset of the Cold War with Western imperialism (a process which resulted in the creation of new bureaucratically degenerated workers states, against the initial intentions of Stalin); and, finally, the continuation of the Cold War in combination with a relative stabilisation of international relations in the 1950s and ’60s, all lengthened the lifetime of the Stalinist bureaucracy for a few decades.

While the extension of Stalinism’s period in power was an important factor in world politics in the second half of the 20th century (and caused much confusion among Marxists), from a historical point of view this period represented only a short episode — much shorter than the epochs of the slaveholder society, the Asiatic mode of production, feudalism or capitalism, which lasted for centuries or millenniums. This, by the way, also confirmed Trotsky’s thesis that the bureaucracy did not constitute a new class but rather a parasitic caste that did not play any necessary role in the production process.

The role of the Stalinist regime in the process of capitalist restoration

The process of revolution and counterrevolution in 1989-92 was a vindication of the Marxist analysis of the anti-proletarian and bourgeoisified character of the Stalinist bureaucracy. The Stalinist bureaucracy did not put up any resistance against the restoration of capitalist property relations. Not only this, the vast majority of the factions within the bureaucracy actively promoted capitalist restoration and became part of the new bourgeoisie. In Eastern Europe, numerous bustling bureaucrats formed companies using their connections and insider knowledge. The former Communist Parties, in general, transformed themselves into pro-capitalist social democratic parties.

In Russia, Boris Yeltsin — the former First Secretary of the Moscow City Committee of the Communist Party — became the first President of capitalist Russia. The bureaucratic-military state machine remained largely intact. Sure, some leading figures in the police, military and justice were purged and institutions were renamed (for example, the KGB became the FSB), while official Soviet institutions were formally dissolved and replaced by parliaments. However, these “Soviets” had nothing in common with the soviets of the October Revolution; they were pseudo-parliamentary institutions with “elections” every four years (in which only the Stalinist party and its allies stood candidates). In its essence, the state machinery — with its key institutions of police, standing army, justice and the bureaucracy — did not undergo substantial changes.

In other countries, the process of capitalist restoration under the Stalinist bureaucracy was even more visible. In several Central Asian countries, the ruling party merely renamed itself (e.g. from Communist Party of Uzbekistan to People's Democratic Party of Uzbekistan or from Communist Party of Kazakhstan to Socialist Party). But the same parties, with the same bureaucracy and the same leaders, essentially remained in power for many years. Leaders simply mutated from “First Secretary” of the regional Communist Parties into “President” of the newly independent republics (for example, Nursultan Nazarbayev in Kazakhstan, Saparmurat Niyazov in Turkmenistan and Islam Karimovin in Uzbekistan).

Similarly, Slobodan Milošević, who led the Stalinist party in Serbia, renamed his party in 1990 and continued to rule the country, now based on capitalist property relations, until his overthrow in 2000. The same with Momir Bulatović in Montenegro, who renamed the ruling party into Democratic Party of Socialists and continued to rule as President.

In Azerbaijan, long-time Stalinist leader Heydar Aliyev, who was First Secretary of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan from 1969-82 and then First Deputy Premier of the Soviet Union from 1982-87, carried out a military coup in 1993. He ruled the country until his death in 2003, when he was succeeded by his son Ilham Aliyev. A similar example is Alexander Lukashenko, a former Soviet bureaucrat who has ruled Belarus since 1994.

In China, Vietnam, Laos, North Korea29 and Cuba,30 the Communist Parties did not rename themselves but carried out a series of market reforms resulting in the restoration of capitalism.

While capitalist restoration could proceed under the leadership of the same Stalinist parties (sometimes with a different name, sometimes with the same name) and the same leaders, it is impossible that a political revolution against these Stalinist regimes could have taken place with the same parties and leaders. Instead, all workers’ uprisings took place exactly against these parties and leaders. This confirms the thesis that the petty-bourgeois Stalinist bureaucracy was much closer to the bourgeoisie than the working class, and that social counterrevolution could take place without the smashing of the Stalinist-Bonapartist state apparatus (in contrast to a successful political revolution).

Stalinist bureaucracies, faced with the impasse of the degenerated workers state on which its power rested, essentially followed one of three different paths: it disintegrated as a political force with sections transforming into capitalists; it formally renamed its party and leading institutions but basically the same forces continued to rule; or it continued its rule under the same name and the same leaders. However, in all cases, it implemented the restoration of capitalism and transformed itself into or fused with the new bourgeoisie.

In this context, it is worth remembering a warning Trotsky made back in 1930, at a time when he still considered the bureaucratic degeneration of the Soviet Union was not so advanced and that the state could be purged of Stalinist rule by way of reform under the pressure of the masses (rather than requiring a new political revolution — a conclusion he drew only in 1936).

When the Opposition spoke of the danger of Thermidor, it had in mind primarily a very significant and widespread process within the party: the growth of a stratum of Bolsheviks who had separated themselves from the masses, felt secure, connected themselves with nonproletarian circles, and were satisfied with their social status, analogous to the strata of bloated Jacobins who became, in part, the support and prime executive apparatus of the Thermidorean overturn in 1794, thus paving the road for Bonapartism. In this analysis of the processes of Thermidorean degeneration in the party, the Opposition was far from saying that the counterrevolutionary overturn, were it to occur, would necessarily have to assume the form of Thermidor, that is, of a more or less lasting domination by the bourgeoisified Bolsheviks with the formal retention of the Soviet system, similar to the retention of the Convention by the Thermidoreans. History never repeats itself, particularly when there is such a profound difference in the class base. (…)

The state form that a counterrevolutionary overthrow in Russia would assume were it to succeed-and that is far from simple depends upon the combination of a number of concrete factors: firstly, on the degree of acuteness of the economic contradictions at the moment, the relation between the capitalist and socialist elements in the economy; secondly, on the relation between the proletarian Bolsheviks and the bourgeois "Bolsheviks" and on the relation of forces in the army; and finally, on the specific gravity and character of foreign intervention. In any event, it would be the height of absurdity to think that a counterrevolutionary regime must necessarily go through the stages of the Directorate, the Consulate, and the Empire in order to be capped by a restoration of czarism. Whatever form the counterrevolutionary regime might take, Thermidorean and Bonapartist elements would find their place in it, a larger or smaller role would be played by the Bolshevik-Soviet bureaucracy, civil and military, and the regime itself would be the dictatorship of the sword over society in the interests of the bourgeoisie and against the people. This is why it is so important today to trace the formation of these elements and tendencies within the official party, which, under all conditions, remains the laboratory of' the future: under the condition of uninterrupted socialist development or under the condition of a counterrevolutionary break.31

Trotsky recognised the process of bourgeoisification of the Stalinist bureaucracy as early as 1930. This process only became much more advanced over the next 20, 40, and 60 years. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that in the late ’80s the bureaucracy showed no resistance to capitalist restoration and instead promoted it.

Excurse: On the role of the state in socio-economic transformations

In this essay we have explained how the same Stalinist bureaucracy first administered and defended proletarian property relations in the period of the degenerated workers’ states, and then implemented the restoration of capitalism in 1989-92. This might appear contradictory to people who think in a mechanical, undialectical way. However, history has had various examples where one and the same regime, one and the same state apparatus, first administered and defended one set of relations of production and then introduced another one. In other words, the form of the regime remained the same, while the character of the economy on which it rested changed.

The Byzantine Empire, which lasted from the 4th century until 1453, was initially based on a slaveholder economy, as it initially formed the Eastern part of the Roman Empire. However, the ruling imperial dynasties oversaw the development of feudal property relations between the 6th and 9th century.

Likewise, imperial dynasties such as the Hohenzollern in Prussia/Germany, the Habsburgs in Austria-Hungary and the Romanovs in Russia, ruled their empires for centuries. Their state apparatus, based on the nobility and linked with large landowners, ruled and administered these territories first in the period of feudalism. However, in the course of the 19th century, they encouraged, to varying degrees, the creation of a bourgeoisie and capitalist property relations, opened the country to foreign investors, etc. In short, the old regime, though initially based on feudalism, introduced new capitalist relations of production. They first served the feudal landowner class and, later, served the bourgeoisie.

The Chinese Qing dynasty and the sultanate of the Ottoman Empire are other examples. These regimes lasted for centuries and were initially based on specific property relations that Marx called the Asiatic mode of production (with varying elements of feudalism). However, due to economic decline and domestic turmoil, these regimes were forced to open their territories to foreign powers which, in turn, resulted in the expansion of capitalist relations of production. Here too, we can see one and the same regime first serving the despotic bureaucracy and nobility and, later, serving the class of foreign capitalists.

Conclusions

To summarise the main findings of our study and draw some relevant conclusions for our analysis of capitalist restoration and the role of the Stalinist bureaucracy:

- The oppression of the working class in the Soviet Union and the annihilation of its vanguard resulted in a political counterrevolution. While the bureaucracy could not and did not abolish post-capitalist, planned property relations at that time, it destroyed the organs of working-class power, such as democratic Soviets and armed forces under popular control. Through this it recreated a bureaucratic-military state machine similar in form to those of capitalist states. While the bureaucracy, for a certain period, administered and defended the social foundations of the workers’ state with this machine, it built a state machine that would become a huge (and, in the end, insurmountable) obstacle for the liberation struggle of the masses.

- The Stalinist caste and its bureaucratic-military state machine had an anti-proletarian character from the very beginning. The bureaucracy was a petty-bourgeois force whose political power and privileges rested on the resources of the state machinery it imposed on the socio-economic foundation of the workers state. As a social base for its rule, it created a social layer of labour aristocracy. The Stalinist bureaucracy and its state machine were alien class forces, which usurped and utilised the workers’ state for their own social interests.

- The bureaucracy was prepared to defend this state through its own non-revolutionary methods as long and insofar as the workers state — whose socio-economic basis the Stalinists distorted and misused — provided it with sufficient privileges. At the same time, the bureaucratic caste permanently oppressed the working class, as only an atomised masses could allow the Stalinists to utilise state resources for their own advantage.

- In its form, the Stalinist state machine had a bourgeois character; separated from and without any control by the masses, it was similar to the key institutions of the capitalist state (police, standing army, justice and the bureaucracy). This machine was, first and foremost, an instrument to control and suppress the working class and popular masses.

- The task of the proletarian revolution in Stalinists states was to smash this bureaucratic-military state machine. That is why a peaceful transformation was not possible, as seen by the brutal oppression of workers’ uprisings against the Stalinists.

- Revolutionaries could advocate a temporary united front tactic with the Stalinist bureaucracy only when, and insofar as, it was defending degenerated workers’ states against imperialist counterrevolution (for example, in the Korean War, in campaigns for disarmament in imperialist countries, in anti-NATO mobilisations in the 1980s). However, the strategic and ever-present task of revolutionaries was to defend the working class and oppressed peoples against the totalitarian rule of the bureaucratic caste.

- In contrast, the peaceful restoration of capitalism was possible because the Stalinist bureaucracy was already much closer to capitalism and could transform itself into a new capitalist bureaucracy and capitalist entrepreneurs. The similarity of the Stalinist and bourgeois state institutions allowed such a process of capitalist restoration without major upheavals in the state apparatus. Capitalist counterrevolution did not require the smashing of the Stalinist bureaucratic-military state machine. In a number of cases, the ruling Stalinist party and its leaders carried out capitalist restoration themselves (in some cases they renamed their parties and positions; in other cases it was done under the same banner of “socialism”).

- The restoration of capitalism in China by the “Communist” Party is not a unique case. Similar developments occurred in Vietnam, Laos, North Korea and Cuba and, albeit in a different form, in several countries in Central Asia, Caucasus, Eastern Europe and the Balkans.

Michael Pröbsting is a socialist activist and writer. He is the editor of the website thecommunists.net where a version of this article first appeared.

- 1

Michael Pröbsting: On the specific class character of China’s ruling bureaucracy and its transformation in the past decades, https://links.org.au/specific-class-character-chinas-ruling-bureaucracy-and-its-transformation-past-decades

- 2

See Harold R. Isaacs: The Tragedy of the Chinese Revolution (1938), Haymarket Books, Chicago 2009

- 3

See: Workers Power: The Degenerated Revolution. The origins and nature of the Stalinist states, Chapter: The Chinese Revolution, London 1982, pp. 54-59. See also Peng Shu-Tse: The Chinese Communist Party in Power, Monad Press, New York 1980, pp. 49-170

- 4

On capitalism in China and its transformation into a Great Power, see Michael Pröbsting: Anti-Imperialism in the Age of Great Power Rivalry. The Factors behind the Accelerating Rivalry between the U.S., China, Russia, EU and Japan. A Critique of the Left’s Analysis and an Outline of the Marxist Perspective, RCIT Books, Vienna 2019, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/anti-imperialism-in-the-age-of-great-power-rivalry/; also by the same author: “Chinese Imperialism and the World Economy”, an essay published in the second edition of The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Imperialism and Anti-Imperialism (edited by Immanuel Ness and Zak Cope), Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2020, https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007%2F978-3-319-91206-6_179-1; "China: An Imperialist Power … Or Not Yet? A Theoretical Question with Very Practical Consequences! Continuing the Debate with Esteban Mercatante and the PTS/FT on China’s class character and consequences for the revolutionary strategy", 22 January 2022, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/china-imperialist-power-or-not-yet/; "China‘s transformation into an imperialist power. A study of the economic, political and military aspects of China as a Great Power (2012)", in: Revolutionary Communism No. 4, https://www.thecommunists.net/publications/revcom-1-10/#anker_4; "How is it possible that some Marxists still Doubt that China has Become Capitalist? An analysis of the capitalist character of China’s State-Owned Enterprises and its political consequences", 18 September 2020, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/pts-ft-and-chinese-imperialism-2/; "Unable to See the Wood for the Trees. Eclectic empiricism and the failure of the PTS/FT to recognize the imperialist character of China", 13 August 2020, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/pts-ft-and-chinese-imperialism/; "China’s Emergence as an Imperialist Power", in: New Politics, Summer 2014 (Vol:XV-1, Whole #: 57).

- 5

Friedrich Engels: The Origin of the Family, Private Property and State, in: MECW Vol. 26, p. 269

- 6

V. I. Lenin: "The State" (1919), in: LCW Vol. 29, p. 475

- 7

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels: Manifesto of the Communist Party, in: MECW Vol. 6, p. 486

- 8

V. I. Lenin: The State and Revolution. The Marxist Theory of the State and the Tasks of the Proletariat in the Revolution; in: CW Vol. 25, p. 407

- 9

Karl Marx: Capital Vol. III, in: MECW 37, pp. 777-778

- 10

See League for a Revolutionary Communist International: "Marxism, Stalinism and the theory of the state", in: Trotskyist International No. 23 (1998), pp. 33-43 (written by Mark Abram and Clare Watson)

- 11

Karl Marx: "Letter to Ludwig Kugelmann" (12. April 1871); in: MECW 44, S. 131

- 12

See Michael Pröbsting: "Capitalism Today and the Law of Uneven Development: The Marxist Tradition and its Application in the Present Historic Period", in: Critique, Journal of Socialist Theory, Vol. 44, 2016, pp. 381-418

- 13

Friedrich Engels: "Letter to Joseph Bloch" (1890); in: MECW 49, pp. 34-35

- 14

V. I. Lenin: "The Dual Power" (1917), in LCW Vol. 24, pp. 38-39

- 15

See Workers Power: The Degenerated Revolution. The origins and nature of the Stalinist states, Chapter: From soviet power to soviet Bonapartism – the degeneration of the Russian Revolution. See also Wadim S. Rogowin: Trotzkismus. Gab es eine Alternative? Vol. 1, Mehring Verlag, 2010

- 16

This and the next two sub-section are largely based on excerpts from Michael Pröbsting: Cuba's Revolution Sold Out? The Road from Revolution to the Restoration of Capitalism, August 2013, RCIT Books, pp. 43-55

- 17

Leon Trotsky: "The Bonapartist Philosophy of the State"; in: Trotsky Writings, 1938-39, Pathfinder, New York 1974, p. 325

- 18

Leon Trotsky: "Not a Workers' and not a Bourgeois State?" (1937); in: Trotsky Writings, 1937-38, p. 61

- 19

Leon Trotsky: "Not a Workers' and not a Bourgeois State?" (1937); in: Trotsky Writings, 1937-38, pp. 65-67

- 20

See Leon Trotsky: 1905 (1909), (in particular pp. 3-9 and chapter “On the Special Features of Russia’s Historical Development - A Reply to M. N. Pokrovsky”, pp. 273-287), Haymarket Books, Chicago 2016; Leon Trotsky: History of the Russian Revolution (1930), Haymarket Books, Chicago 2016, pp. 3-12; M. N. Pokrovsky: History of Russia. From the Earliest Times to the Rise of Commercial Capitalism, International Publishers, New York 1931; by the same author: Russia in World History; Selected Essays, Edited by Roman Szporluk, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor 1970; Geschichte Russlands von seiner Entstehung bis zur neuesten Zeit, C.L.Hirschfeld Verlag, Leipzig 1929; Russische Geschichte, Berlin 1930; M. N. Pokrowski: Historische Aufsätze. Ein Sammelband, Verlag für Literatur und Politik, Wien und Berlin 1928;

- 21

Leon Trotsky: "Preface to Norwegian edition of My Life" (1935); in: Trotsky Writings, Supplement 1934-40, New York 1979, p. 619

- 22

Leon Trotsky: "Not a Workers' and not a Bourgeois State?" (1937); in: Trotsky Writings, 1937-38, p. 63

- 23

Leon Trotsky: "The Death Agony of Capitalism and the Tasks of the Fourth International: The Mobilization of the Masses around Transitional Demands to Prepare the Conquest of Power (The Transitional Program)"; in: Documents of the Fourth International. The Formative Years (1933-40), New York 1973, p. 212.

- 24

Leon Trotsky: The Revolution Betrayed (1936), Pathfinder Press 1972, pp. 252-253

- 25

See League for a Revolutionary Communist International: "Marxism, Stalinism and the theory of the state", in: Trotskyist International No. 23 (1998), pp. 33-43.

- 26

Leon Trotsky: "The Bonapartist Philosophy of the State" (1939); in: Trotsky Writings, 1938-39, New York 1974, pp. 324-325 (emphasis in original)

- 27

Leon Trotsky: The Revolution Betrayed, p. 252

- 28

Leon Trotsky: The Revolution Betrayed, pp. 253-254

- 29

On the issue of capitalist restoration in North Korea see Michael Pröbsting: "Has Capitalist Restoration in North Korea Crossed the Rubicon or Not? Reply to a Polemic of Władza Rad" (Poland), 15 July 2018, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/has-capitalist-restoration-in-north-korea-crossed-the-rubicon-or-not/; Michael Pröbsting: "In What Sense Can One Speak of Capitalist Restoration in North Korea? Reply to Several Objections Raised by the Polish Comrades of 'Władza Rad'." 21 June 2018, https://www.thecommunists.net/theory/north-korea-and-the-marxist-theory-of-capitalist-restoration/; Michael Pröbsting: "Again on Capitalist Restoration in North Korea", 12 June 2018, https://www.thecommunists.net/worldwide/asia/again-on-capitalist-restoration-in-north-korea/; Michael Pröbsting: "World Perspectives 2018: A World Pregnant with Wars and Popular Uprisings", pp. 95-105

- 30

See Cuba's Revolution Sold Out.

- 31

Leon Trotsky: "Thermidor and Bonapartism" (1931), in: Trotsky Writings 1930-31, pp. 75-76, Internet: https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1931/xx/thermbon.htm