A Gandhi We Didn’t Know: A Reassessment Of An Avant-Garde – OpEd

Mahatma Gandhi, the iconic figure of India’s independence struggle, has been enshrined in the nation’s collective memory as a paragon of non-violence, secularism, and social justice. Yet, a closer examination of his life and legacy reveals a more complex and often contradictory character. This analysis seeks to challenge the conventional wisdom surrounding Gandhi, offering a critical reassessment that draws on both historical evidence and contemporary political theory.

Mahatma Gandhi’s image, often glorified as the father of Indian independence, overlooks the more controversial aspects of his political and social ideologies. While remembered for his philosophy of non-violence and efforts to unite India, Gandhi’s views on Hinduism, race, and political compromise reveal a figure far more complex. These hidden dimensions, often ignored in popular narratives, continue to shape India’s contemporary political landscape.

Hindu Nationalism in Gandhi’s Political Vision

Gandhi’s early writings and speeches often used Hinduism as a moral framework. He spoke of Hind Swaraj—self-rule not just as political independence but as spiritual regeneration grounded in Hindu values. His insistence on the spinning wheel as a symbol of self-reliance was deeply rooted in Hindu ideals of simplicity and self-sacrifice.

Yet, Gandhi’s alignment with Hindu symbols sparked controversies. His opposition to the partition of India in 1947 stemmed partly from a belief that a united India could thrive under Hindu moral leadership. Though he called for harmony between Hindus and Muslims, his stance often alienated Muslim leaders like Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Gandhi’s tacit support for policies such as cow protection laws, rooted in Hindu tradition, also fostered resentment among Muslims.

Today, this legacy plays out in India’s political dynamics. The rise of the **Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, hinges on an ideology of Hindutva, a form of Hindu nationalism. Though the BJP celebrates Gandhi’s contributions, it leans on his Hindu nationalism to further policies aimed at securing the interests of the Hindu majority. The contradiction is stark: Gandhi’s assassin, Nathuram Godse, was a staunch Hindu nationalist. The BJP’s use of Gandhi’s image while promoting religious intolerance shows the malleability of historical figures in political narratives.

Gandhi’s Troubling Views on Race

Gandhi’s time in South Africa, where he first engaged in political activism, exposes a more uncomfortable facet of his ideology. Though he championed rights for Indians, he showed little solidarity with Black South Africans. Gandhi’s writings from that period describe Africans in derogatory terms, depicting them as “uncivilized” and calling for Indian racial superiority.

Gandhi supported the idea of separate facilities for Indians and Africans, advocating for privileges for Indians within the framework of racial segregation. While this position reflected colonial attitudes of the time, it clashes with his later image as a global advocate for human dignity. His stance in South Africa complicates his legacy as a champion of equality.

The backlash against Gandhi’s legacy in countries like South Africa is growing. Statues of him have been defaced, and calls for reassessment are mounting. For a global audience increasingly focused on racial justice, Gandhi’s past remains a reminder that even revered leaders carried deeply flawed beliefs.

Non-Violence and Political Pragmatism

Gandhi’s strategy of non-violent resistance was groundbreaking in its ability to mobilize millions against British colonial rule. His philosophy of ahimsa(non-violence) remains one of his most enduring legacies. The Salt March of 1930 exemplified his method of symbolic protest, directly challenging British authority without resorting to violence.

Yet Gandhi’s commitment to non-violence faced practical limits. In 1922, following the violent Chauri Chaura incident where Indian protesters killed 22 policemen, Gandhi abruptly suspended the Non-Cooperation Movement, shocking many of his followers. His moral rigidity frustrated others in the movement, such as Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose, who saw violence as an unfortunate but necessary aspect of revolutionary struggle.

Gandhi’s compromises also reveal his pragmatic side. The Gandhi-Irwin Pact of 1931 ended the Civil Disobedience Movement in exchange for minimal concessions from the British government. Many saw this as a betrayal, questioning Gandhi’s tendency to seek gradual reforms rather than push for sweeping change. His pragmatic approach often alienated younger and more radical figures in the independence movement, widening a rift between Gandhi’s idealism and the realpolitik of leaders like Bose.

Gandhi’s Legacy in Modern India

The contradictions in Gandhi’s thought have rippled through modern India’s political, economic, and social fabric. His vision of a self-reliant, agrarian India, while well-intentioned, seems outdated in a nation that now aspires to be a global economic leader. Gandhi’s push for village-centric development opposed large-scale industrialization, a position incongruent with the economic priorities of today’s India, which seeks urbanization, technological growth, and global trade.

Gandhi’s emphasis on religious tolerance contrasts sharply with the increasingly divisive nature of Indian politics today. While secularists often invoke Gandhi’s ideals to argue for a pluralistic society, political factions like the BJP manipulate his image to justify their majoritarian agenda. By selectively highlighting aspects of his Hinduism, they sidestep Gandhi’s broader commitment to unity across religions.

In contemporary India, issues like economic inequality, religious polarization, and environmental degradation demand solutions beyond Gandhi’s original prescriptions. His critique of materialism resonates amid rising inequality, but his economic vision—favoring small-scale industry and self-reliant communities—falls short of addressing the demands of a globalized economy. Gandhi’s teachings on non-violence provide moral guidance, but his inability to fully engage with the complexities of modern governance limits the applicability of his ideas in tackling India’s pressing challenges.

The Gandhi We Didn’t Know

The sanitized version of Gandhi’s legacy—a symbol of non-violence and tolerance—ignores the complexities that defined his political life. His flirtation with Hindu nationalism laid the groundwork for sectarian divides that persist in India’s politics. His racial prejudices in South Africa tarnish his global image as a human rights advocate. His compromises during the independence movement underscore the tensions between moral idealism and political pragmatism.

Gandhi’s legacy remains relevant, but it requires critical reassessment in light of contemporary challenges. India, facing widening inequalities, communal tensions, and environmental crises, can still draw from Gandhi’s ideals, but not without acknowledging the limitations of his philosophy. The “Gandhi we didn’t know”—a man whose political beliefs carried internal contradictions—offers lessons both as an inspiration and as a cautionary tale.

In a world increasingly polarized by religion, race, and politics, Gandhi’s life serves as a reminder of the complexities behind revolutionary leadership. As India continues to grapple with its identity, the real Gandhi—flawed, human, and bound by the context of his time—deserves renewed attention. Understanding the full scope of his contributions and shortcomings is crucial to navigating the future of Indian democracy.

Gandhi’s ideas may still have a role to play in guiding India forward, but the time for idolizing him as an infallible figure has long passed. It is the nuances and contradictions in his legacy that hold the greatest potential for reflection and growth.

Debashis Chakrabarti

Debashis Chakrabarti is an international media scholar and social scientist, currently serving as the Editor-in-Chief of the International Journal of Politics and Media. With extensive experience spanning 35 years, he has held key academic positions, including Professor and Dean at Assam University, Silchar. Prior to academia, Chakrabarti excelled as a journalist with The Indian Express. He has conducted impactful research and teaching in renowned universities across the UK, Middle East, and Africa, demonstrating a commitment to advancing media scholarship and fostering global dialogue.

A statue has been unveiled in honour of Betty Campbell, Wales’s first Black headteacher. Image: Cardiff Council

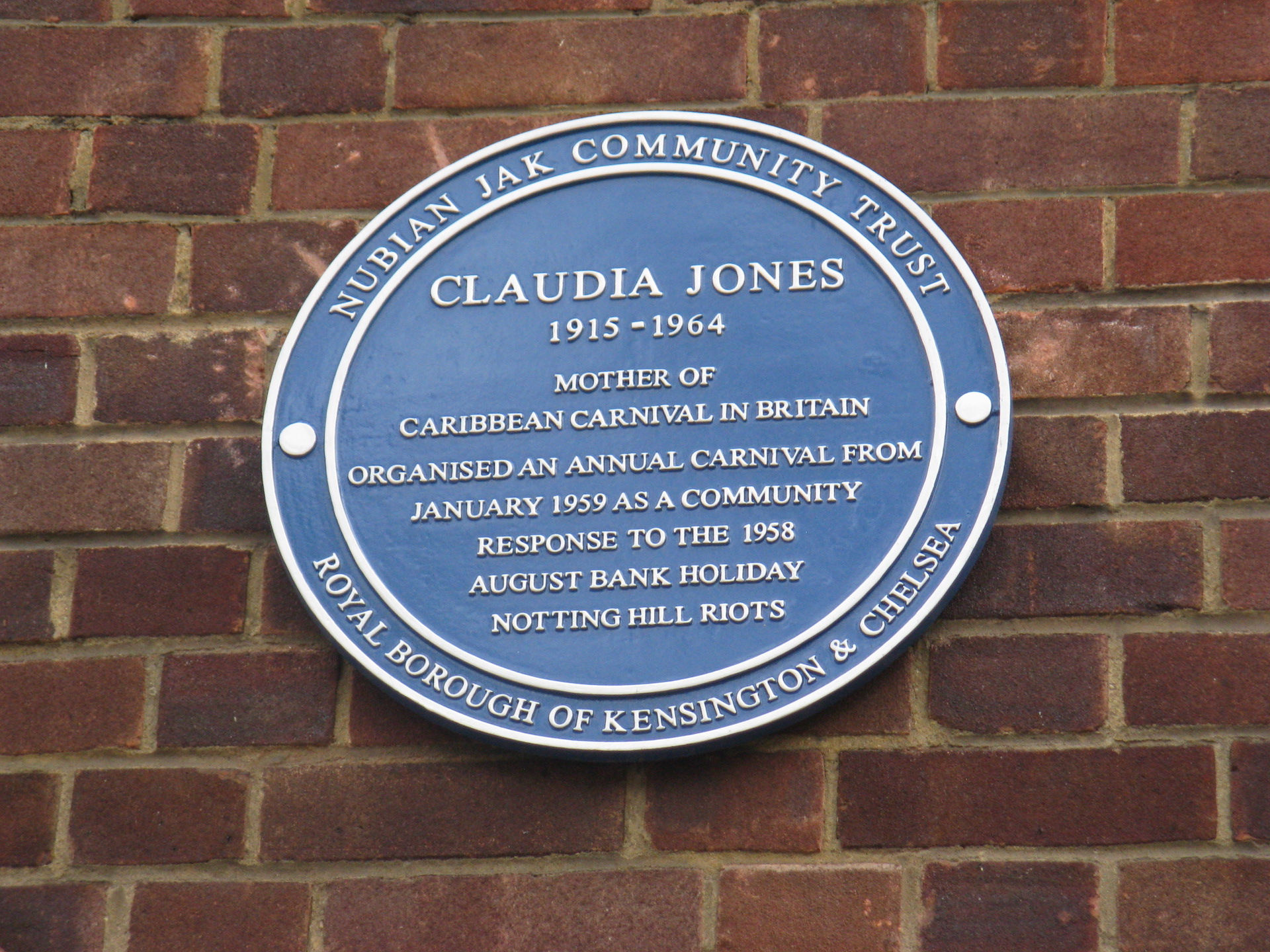

A statue has been unveiled in honour of Betty Campbell, Wales’s first Black headteacher. Image: Cardiff Council Claudia Jones was a stalwart campaigner for the rights of Black people in the UK and founder of what became the Notting Hill Carnival. Image:

Claudia Jones was a stalwart campaigner for the rights of Black people in the UK and founder of what became the Notting Hill Carnival. Image: