Remembering Gustavo Gutiérrez

(RNS) — A group of priests, most of us working in parishes in the slums, met with Gutiérrez to talk about our experiences. Only later did we realize that what he told us in return were the first moments of what would come to be called liberation theology.

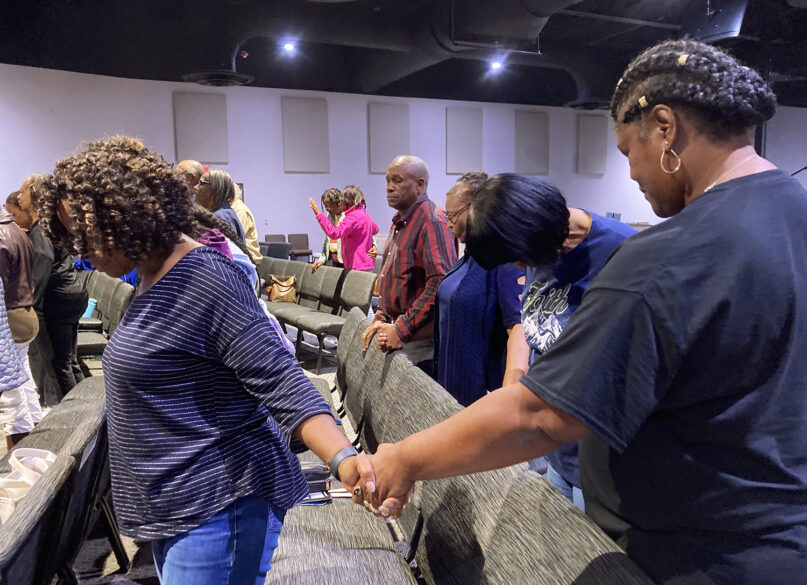

Peruvian theologian Gustavo Gutiérrez attends a news conference at the Vatican, May 12, 2015. (AP Photo/Alessandra Tarantino)

Joseph Nangle

October 30, 2024

(RNS) — On an ordinary weekday in the basement of a downtown church in Lima, Peru, in the late 1960s, a gathering of priests, most of them working in slum parishes, heard theology being done in an entirely new way: from the bottom up, based on day-to-day events, working from practice to theory.

Only later did we realize that something quite remarkable was taking place, and that we were experiencing the first moments of what would come to be called liberation theology.

The leader of the group was the Rev. Gustavo Gutiérrez, a Catholic priest who was leading the discussion that day. It was there that I first heard Gutiérrez, who died Oct. 22, say, “I think the Exodus story in the Hebrew Scriptures has much to do with what we are doing here — the movement of a people from slavery to freedom: liberation.”

For several months he had invited us to meet with him weekly and share our pastoral experiences from the slum parishes where most of us we worked. Gustavo would simply listen as we spoke of the events taking place in our ministries, then, at the end, sum up what he had been hearing. We never sensed he was there to instruct or correct us. In fact, he sometimes remarked that the events we were describing were “the raw material for his theologizing.”

As the term “liberation theology” went viral, Gustavo expanded his initial reflections on this process, saying we were grappling with a fundamental question: Does God’s Word (the Holy Scriptures) have anything to say to the poor of the earth? The best way to begin answering that question, he said, was to look at the experience all around us in the so-called Third World of poor, marginalized, oppressed human beings.

Today the answer to that question and its instinctive affirmative reply is readily agreed upon: “Yes, of course, a principal theme in God’s Word to us concerns the poor among us.” At that time and place, however, this answer was not so clear. The institutional Catholic Church in Latin America was identified with powerful forces – economic, political and military elements that maintained an iron grip on the generally impoverished lives of its citizens. One archbishop in Peru celebrated the fact of so many poor, saying “this allowed the church the opportunity to be charitable toward them!”

The question about God’s Word and the recognition of victims of “institutionalized oppression” — another insight of liberation theology — were keys to understanding this “new grace” in theological terms, and, more importantly, in Catholic spirituality and pastoral practice. It turned the entire process of theologizing on its head, from ethical and doctrinal propositions to a new beginning place: reality. One can make the case now that this process has become a norm in most theological circles, even without labeling it liberation theology.

Gutierrez’s instinct about reflecting and acting on human experiences as the starting place for understanding God’s Word to humanity ran into serious obstacles. The most famous of these was the reaction of St. John Paul II and then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) at the Vatican. As the inevitable consequences of entire communities of oppressed people beginning to learn of God’s liberating Word, the Vatican leaders reacted sometimes violently against their status quo.

One can conjecture that the Polish pope and his German theologian moved from their deeply felt opposition to communism. They felt that poor people were being incited to Marxist-style revolution such as those the hierarchs had experienced, particularly in Soviet-dominated countries.

This attitude was 180 degrees apart from the intent of liberation theology. One cannot continue to oppress a people. They will protest. In the Bible’s Book of Exodus, we hear the Lord say, “I have heard the cry of the poor,” and Moses say, “Let my people go.” Liberation theology brought this consciousness of God’s will ever more clearly to oppressed human beings in Latin America and eventually far beyond. This is Gutierrez’s lasting and glowing legacy.

Sometime after my return from Peru to the United States in 1975, Gustavo called me to ask if I would approach an American religious superior and urge him to intervene with a member of his congregation in Peru. The superior was influential in many circles there and was undermining liberation consciousness among the people. Gustavo’s comment on that occasion is significant: “What’s important is not some arcane argument among armchair theologians, but essential for the popular organizations being moved by this new understanding of their religion.”

This request speaks of the importance that liberation theology has come to represent not only for marginalized people but for the Catholic Christian world and beyond. Judging, challenging, interpreting the Word of God by its relevance in ordinary life is a new spirituality. Gustavo was very strong on this point, often insisting with us who were engaged in ministry that the message of a liberating God was essentially a pastoral task.

In that and many other ways, Gustavo was a dedicated and faith-filled son of the Catholic Church. His adherence to it, despite official opposition from the highest levels of that institution, speaks volumes about his integrity as a loyal member of the church.

As a Christian, a Catholic, a member of the Franciscan order and an ordained priest in those institutions, I can say with utter honesty that Gutierrez has been the most important influence in my life. From a typically conservative cradle Catholic, educated theologically in the decade of the 1950s, I had my eyes opened to a whole new way of praying, celebrating the Catholic sacraments and above all engaging in pastoral work.

I began as a popularizer who saw his vocation as making people happy, without addressing the underlying causes of deep, widespread tragedies in the world. Gustavo opened my eyes. I was never the same again. He showed me that the Hebrew Scriptures and the gospel of Jesus Christ come with an expensive price tag, that of standing with and speaking on behalf of the millions who are denied a voice. And without promoting it, that view of Christianity inevitably provokes deep opposition.

In the words of another “liberationist,” Lutheran pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer, “It is the cost of discipleship.”

(The Rev. Joseph Nangle is a Catholic Franciscan priest. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of RNS.)

(RNS) — While liberation theology has been criticized for a view of oppression that is too simplistic, young Latin American theologians say Gutiérrez opened the doors for new movements in Catholic thought, even as the Vatican warmed to his legacy.

Peruvian theologian Gustavo Gutiérrez speaks during a news conference at the Vatican, May 12, 2015. (AP Photo/Alessandra Tarantino, File)

Eduardo Campos Lima

October 29, 2024

SÃO PAULO (RNS) — The death of the Rev. Gustavo Gutiérrez, called the “father of liberation theology,” at age 96 on Oct. 22 has set off a reconsideration of the theological and pastoral movement spawned by the publication of the Peruvian priest’s 1971 book, “A Theology of Liberation.”

Once a powerful influence on both faith and politics in Latin America, liberation theology grew out of Gutiérrez’s concern for the poor amid the collapse of political projects in the 1960s that tried to modernize the region’s economies, exacerbated by the political repression by military juntas in several South and Central American countries.

The result was widespread violence and poverty — something that, for Gutiérrez and his colleagues, was not natural, but produced by severe social and economic inequality.

“That was the innovation introduced by Gustavo Gutiérrez and others – including myself – when we conceived theology starting from the suffering and oppression faced by the great majority of the Latin American people. The poor are oppressed, and all oppression cries for liberation,” said Leonardo Boff, a Brazilian theologian and a prominent proponent of liberation theology himself, who called Gutiérrez “a dear friend.”

Before writing his book, Gutiérrez had visited Brazil, where a new kind of church organization was already being set in motion by urban and rural workers: so-called basic ecclesial communities, known by their Portuguese and Spanish acronym CEBs, which gathered workers in a given neighborhood into a single community where they could discuss their lives and their faith.

The CEBs inspired Gutiérrez, and his writings spread the CEB model to peasants, landless rural workers, members of Indigenous groups, factory workers and the unemployed.

Liberation theology, however, encountered criticism from Catholic Church leaders, especially in Europe, who said it owed too much to Marxist ideas in its analysis of poverty and was too sympathetic to ideas about violent revolution. Boff recalled that “Gutiérrez’s work was seen as a kind of Trojan horse designed to promote Marxism in Latin America.”

At the same time, the early years of liberation theology were also a time of intense debate as the church absorbed the changes of the Second Vatican Council, and Gutiérrez’s thought was not given its due. “Europeans couldn’t care less about the thought coming from the peripheries, especially about theological or philosophical thought,” Boff said.

But under Pope John Paul II and his doctrine watchdog, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI), the Vatican would closely monitor liberation theology. Boff described how Gutiérrez once had to clarify some of his ideas for Vatican officials and the whole Peruvian episcopate. In 1984, liberation theology was officially censored, and though he was never silenced by Rome himself, Gutiérrez was relegated to the fringes of the church’s theological debates. Meanwhile, the Latin American church saw many of its most progressive leaders replaced by conservative prelates.

With the end of the Cold War a few years later, new ideas changed how Latin American thinkers, especially conservatives, saw politics and societal transformation. New generations of progressive theologians also found themselves rejecting liberation theology’s view of the poor and oppressed.

Over the past few decades, the fragmentation of categories such as “the poor” into smaller social groups and identities has been leading to several new theological movements in Latin America, more focused on the needs and realities of specific segments. Works like Gutiérrez’s may be seen by younger generations as classics from the past in that context.

“We realized that such rhetoric was too broad and nonspecific. Those ‘poor’ had no color. We’re all poor, but some of us are racialized, some of us are Black or Indigenous, some of us are women,” Colombian theologian Maricel Mena López, a professor at the Santo Tomas University in Bogota, told RNS.

A proponent of Black feminist theology, Mena said that, little by little, younger theologians also came to see liberation theology as patriarchal. “Apparently, women’s issues were not important in that theology,” she said.

Bolivian theologian Heydi Galarza, an expert in biblical studies, told RNS that the first generation of liberation theology thinkers “had great difficulty grasping the relevance of women’s issues.”

“That has been and continues to be a strong criticism,” Galarza said. “Latin American theology has gone a long way since then, with the development of new schools of thought.”

Both Mena and Galarza agree, however, that Gutiérrez opened the doors for those new movements.

“His theological work made other ones possible. I consider myself to be a liberation theologian – as well as a Black feminist theologian,” Mena said, adding that in her opportunities to talk with Gutiérrez at academic events, he always listened with great attention to all she had to say.

“He was very welcoming of feminist ideas, for instance. I never felt he was critical of them. He even told me, on one occasion, that he was glad that we were seeing things they couldn’t see back then,” she said.

The fact that his theological work started from the reality of social groups and from the practical experience with them still forms the basis for new theological approaches, Galarza said. “That nonspecific view of the poor has been overcome, but the way his theological work related to them — starting from the praxis — is still valid and can be applied to all social groups,” she said.

Pope Francis’ pontificate has also returned some vigor to liberation theology. A longtime acquaintance of Gutiérrez, the pontiff has always rejected what he considers to be “excess” in liberation theology, referring to its Marxist tendencies. But Gutiérrez’s focus on the poor and his preference for concrete theology directly connected to the people are ideas close to the pope’s own.

Indeed, under Francis the Vatican “rehabilitated” Gutiérrez, and he was invited to take part in official meetings there.

Bolivian theologian Tania Avila, a member of the women’s and Indigenous’ hubs of the Catholic Church’s Pan-Amazon Ecclesial Network, known as REPAM, writes on “integral ecology,” a holistic approach to thinking about the environment that Francis included in his 2015 environmental encyclical, “Laudato Si’.” Avila told RNS that she considers Gutiérrez a “brave theologian who challenged his own time’s limitations to see the social context.”

Avila also agreed that Gutiérrez and some of his colleagues “made an effort to recognize, decades later, that they failed to take into consideration the feeling and thinking of the women in their theological work.”

Francisco Bosch, a young Argentine theologian who has been accompanying the Latin American CEBs as an adviser to the Episcopal Conference of Latin America, said he feels close to Gutiérrez. “Theology, for him, is a love letter between God and his people. The work of the theologian is about that letter. And we’re living amid projects of hatred in Latin America,” Bosch told RNS.

In a time of political crisis and a general feeling of lack of representation, of economic hardships and environmental catastrophes, “Gutiérrez’s words are more urgent than ever,” Bosch said.

“His thought is part of the great Judeo-Christian tradition, which still has much to offer to humankind, especially in times of disorientation,” said Bosch. The “struggles of different social groups — Blacks, Indigenous, women and so on — converge and strengthen each other, telling the same narrative of emancipation when their agents discover that God walks with them.”