Climate Change and the Insurability Crisis

Storm-ravaged house, Knappa, Oregon. Photo: Jeffrey St. Clair.

Home insurance rates are rising in the United States, not only in Florida, which saw tens of billions of dollars in losses from hurricanes Helene and Milton, but across the country.

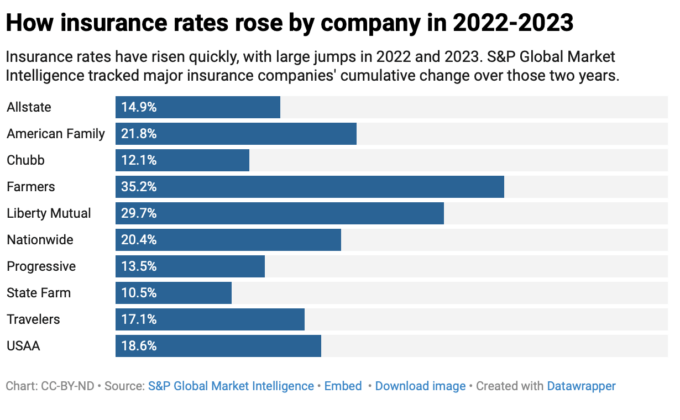

According to S&P Global Market Intelligence, homeowners insurance increased an average of 11.3% nationwide in 2023, with some states, including Texas, Arizona and Utah, seeing nearly double that increase. Some analysts predict an average increase of about 6% in 2024.

These increases are driven by a potent mix of rising insurance payouts coupled with rising costs of construction as people build increasingly expensive homes and other assets in harm’s way.

When home insurance averages $2,377 a year nationally, and $11,000 per year in Florida, this is a blow to many people. Despite these rising rates, Jacques de Vaucleroy, chairman of the board of reinsurance giant Swiss Re, believes U.S. insurance is still priced too low to fully cover the risks.

It isn’t just that premiums are changing. Insurers now often reduce coverage limits, cap payouts, increase deductibles and impose new conditions or even exclusions on some common perils, such as protection for wind, hail or water damage. Some require certain preventive measures or apply risk-based pricing – charging more for homes in flood plains, wildfire-prone zones, or coastal areas at risk of hurricanes.

Homeowners watching their prices rise faster than inflation might think something sinister is at play. Insurance companies are facing rapidly evolving risks, however, and trying to price their policies low enough to remain competitive but high enough to cover future payouts and remain solvent in a stormier climate. This is not an easy task. In 2021 and 2022, seven property insurers filed for bankruptcy in Florida alone. In 2023, insurers lost money on homeowners coverage in 18 states.

But these changes are raising alarm bells. Some industry insiders worry that insurance may be losing its relevance and value – real or perceived – for policyholders as coverage shrinks, premiums rise and exclusions increase.

How insurers assess risk

Insurance companies use complex models to estimate the likelihood of current risks based on past events. They aggregate historical data – such as event frequency, scale, losses and contributing factors – to calculate price and coverage.

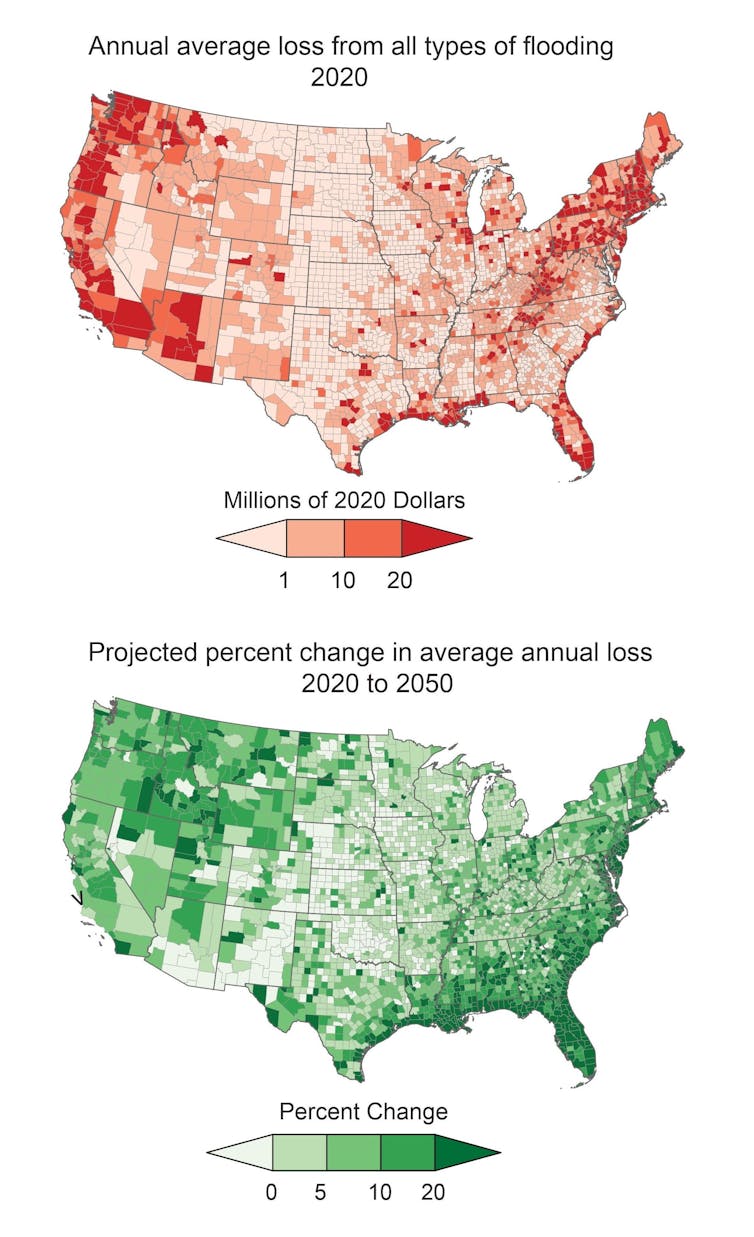

However, the increase in disasters makes the past an unreliable measure. What was once considered a 100-year event may now be better understood as a 30- or 50-year event in some locations.

What many people do not realize is that the rise of so-called “secondary perils” – an insurance industry term for floods, hailstorms, strong winds, lightning strikes, tornadoes and wildfires that generate small to mid-size damage – is becoming the main driver of the insurability challenge, particularly as these events become more intense, frequent and cumulative, eroding insurers’ profitability over time.

Climate change plays a role in these rising risks. As the climate warms, air can hold more moisture – about 7% more with every degree Celsius of warming. That leads to stronger downpours, more thunderstorms, larger hail events and a higher risk of flooding in some regions. The U.S. was on average 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.6 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer in 2022 than in 1970.

Insurance companies are revising their models to keep up with these changes, much as they did when smoking-related illnesses became a significant cost burden in life and health insurance. Some companies use climate modeling to augment their standard actuarial risk modeling. But some states have been hesitant to allow climate modeling, which can leave companies systematically underrepresenting the risks they face.

Each company develops its own assessment and geographic strategy to reach a different conclusion. For example, Progressive Insurance has raised its homeowner rates by 55% between 2018 and 2023, while State Farm has raised them only 13.7%.

While a homeowner who chooses to make home improvements, such as installing a luxury kitchen, can expect an increase in premiums to account for the added replacement value, this effect is typically small and predictable. Generally, the more substantial premium hikes are due to the ever-increasing risk of severe weather and natural disasters.

Insurance for insurers

When risks become too unpredictable or volatile, insurers can turn to reinsurance for help.

Reinsurance companies are essentially insurance companies that insure insurance companies. But in recent years, reinsurers have recognized that their risk models are also no longer accurate and have raised their rates accordingly. Property reinsurance alone increased by 35% in 2023.

Reinsurance is also not very well suited to covering secondary perils. The traditional reinsurance model is focused on large, rare catastrophes, such as devastating hurricanes and earthquakes.

Fifth National Climate Assessment

As an alternative, some insurers are moving toward parametric insurance, which provides a predefined payment if an event meets or exceeds a predefined intensity threshold. These policies are less expensive for consumers because the payouts are capped and cover events such as a magnitude 7 earthquake, excessive rain within a 24-hour period or a Category 3 hurricane in a defined geographical area. The limits allow insurers to provide a less expensive form of insurance that is less likely to severely disrupt their finances.

Protecting the consumer

Of course, insurers don’t operate in an entirely free market. State insurance regulators evaluate insurance companies’ proposals to raise rates and either approve or deny them.

The insurance industry in North Carolina, for example, where Hurricane Helene caused catastrophic damage, is arguing for a homeowner premium increase of more than 42% on average, ranging from 4% in parts of the mountains to 99% in some waterfront areas.

If a rate increase is denied, it could force an insurer to simply withdraw from certain market sectors, cancel existing policies or refuse to write new ones when their “loss ratio” – the ratio of claims paid to premiums collected – becomes too high for too long.

Since 2022, seven of the top 12 insurance carriers have either cut existing homeowners policies or stopped selling new ones in the wildfire-prone California homeowner market, and an equal number have pulled back from the Florida market due to the increasing cost of hurricanes.

To stem this tide, California is reforming its regulations to speed up the rate increase approval process and allow insurers to make their case using climate models to judge wildfire risk more accurately.

Florida has instituted regulatory reforms that have reduced litigation and associated costs and has removed 400,000 policies from the state-run insurance program. As a result, eight insurance carriers have entered the market there since 2022.

Looking ahead

Solutions to the mounting insurance crisis also involve how and where people build. Building codes can require more resilient homes, akin to how fire safety standards increased the effectiveness of insurance many decades ago.

By one estimate, investing $3.5 billion in making the two-thirds of U.S. homes not currently up to code more resilient to storms could save insurers as much as $37 billion by 2030.

In the end, if affordability and relevance of insurance continue to degrade, real estate prices will start to decline in exposed locations. This will be the most tangible sign that climate change is driving an insurability crisis that disrupts wider financial stability.

Justin D’Atri, Climate Coach at the education platform Adaptify U and Sustainability Transformation Lead at Zurich Insurance Group, contributed to this article.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.