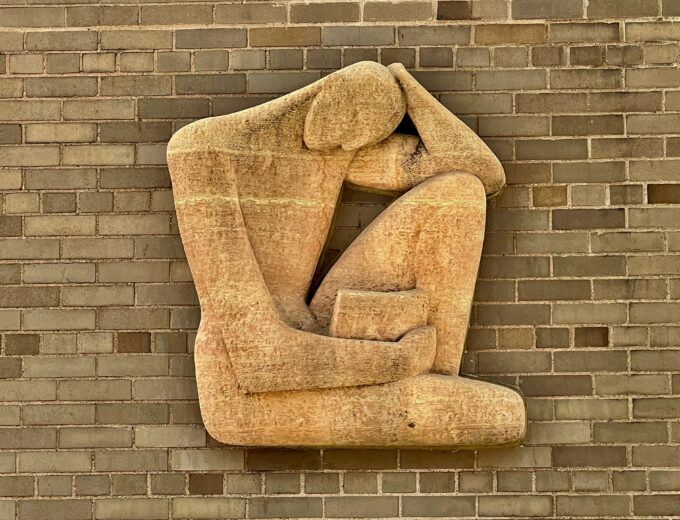

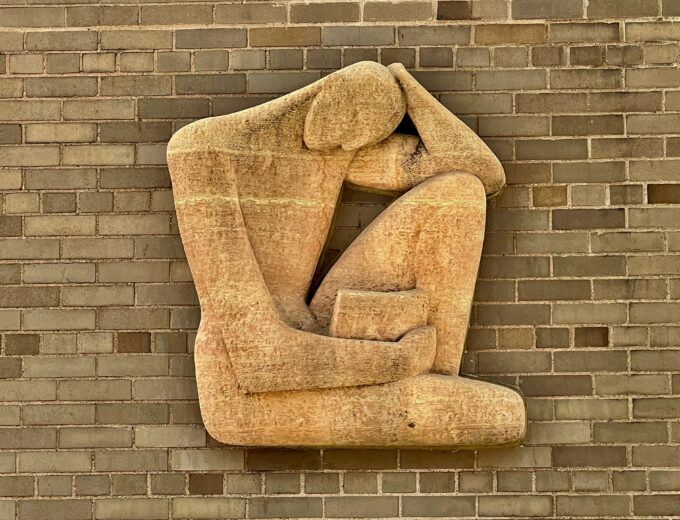

Sculpture, Wayne State University. Photo: Jeffrey St. Clair.

Cybernetic Society and the Descent of Dialectical

Thought

We lack the tools to critically assess and interrogate our social institutions and our

ways of thinking about and interacting with them. That is among the core claims of a new book by Michael J. Thompson, a professor of political theory at William Paterson University and a practicing psychoanalyst. In The Descent of the Dialectic, published earlier this year, Thompson argues that in our age of all-penetrating relativism and the “drastic decline of critical thought in Western culture,” we must attempt to put an objective ethics grounded in critical theory back on firm footing. Thompson wants to address the pervasive nihilism and “dull uniformity” he sees in Western culture, “with the logics of control, efficiency, consumption, and uniformity of all kinds” replacing the project of developing meaning and social values; these developments have tracked the observed decline in critical thinking.

Thompson’s goal, in part, is to address the separation between “objective rationality” and “a substantive and ontological account of human ethics.” Thompson’s book is an attempt to revive the dialectical method through an approach that unites and synthesizes “human value with objectivity rationality” in phronetic criticism. This idea is rooted in the concept of phronesis, which, in the philosophical tradition of the ancient Greeks, counsels a kind of prudence that recognizes the radical contingency and contextuality of life and decision-making. The dialectic recognizes our nature as “affine beings that are intrinsically related with others and shape and form our internal world via our relationality with others.” Students who have been trained in the dialectical approach will be more able to tap into, incorporate, and synthesize these two types of reason. “Increasingly,” writes Thompson, “modern societies are driven not by substantive values concerning human good but by the technical imperatives of economic management, leading to a cultural condition of nihilism that has eroded dialectical consciousness.” It is not enough for Thompson that we rely on deliberation or discussion within a nominally democratic process; this philosophical overreliance on process and dialogue, absent the reintroduction of “critical use of the dialogue,” leaves us stranded in social and political patterns that are not equipped to mount serious challenges to the status quo.

Dialectical thinking encourages us to confront and disrupt the orthodoxies of thought and practice that are “typical of one’s place in the world.” “Opposed to this,” argues Thompson, “is the passive acceptance of the basic structure of this world, of its categories that gradually come to shape our own.” Thompson associates these imperatives with an institutional and normative complex he calls “cybernetic society,” in which consciousness is increasingly absorbed in “this logic of efficiency and productivity.” The phase of cybernetic society we have entered has made it possible for the logics of capitalism “to colonize the deepest reaches of consciousness,” the self withering in a poisoned and atrophied social environment. Thompson returns to the idea of cybernetic society frequently throughout the book to describe a society in which the individual’s self-conception and way of life have been taken over and reconstituted by institutional imperatives and logics. Everything is quantifiable and trackable—your productivity and consumption patterns, your internet use and the ideological character of the content you consume, your personal relationships and connections, your physical location and movements, your biometric data and medical history, your finances and credit history. It is a world of measurable metadata in which very little is beyond the reach of the state and powerful corporations. And while the cybernetic society of the present stage of capitalism promises freedom and individual self-expression and self-realization, the psychological, material, and political conditions of real-life capitalism are profoundly unfree. As Thompson explains, “the subject is allowed to explore only that which can be delivered by the cybernetic society.” Thus, ways of expressing oneself in dress and appearance are increasingly tolerated and even imitated by the ruling class.[1]

The objective, critical ethic Thompson hopes to revive draws heavily on the work of Karl Marx. Marx famously gave us new ways to think about the failures of philosophy to change the world, uniting philosophical interpretation on one side and action toward change on the other. Marx’s own career arguably follows this structure, with a divide between the philosophical early Marx and the political later Marx (debates about the merits of this distinction in his work are beyond the purview of this article). In The Descent of the Dialectic, Thompson is engaged with both, putting a critique of society as it is alongside the presentation of a philosophical approach capable of changing social reality. In discussing the dialectic as an approach to philosophy, it is important to point out that Hegel explicitly dismissed this way of conceiving his project. To Hegel, describing reality is hard enough without adding positive or prescriptive statements. The dialectic is not applied to phenomena from without, but is the attempt to follow and describe dynamics in reality in their immanent natures, to describe things in terms of the tensions that exist within and define reality. Hegel writes that “everything true, in so far as it is comprehended, can be thought of only speculatively,” a statement about the complexity and irreducibility of the world.

In dialectics, truth is associated with a process instead of being held as something fixed and objective one discovers. The goal is to begin to see reality not as a set of discrete facts, but as a complex of “interwoven tendencies.” Whereas the state’s schools teach obedience to various dogmas, a dialectical approach to education would instruct students to disrupt reified social concepts and categories, breaking them down into the component relationships from which they are composed. We can draw on the idea of emergence to help make sense of these relationships: the dialectic offers a way to think about the emergence of complex, unpredictable (and apparently non-deterministic) social patterns by analyzing them in terms of the conflicts and contradictions found within the overall system. By drilling down to these dynamics, we can develop a fuller and more accurate picture or model of the social ontological landscape; it takes seriously the role of power and structural inequalities in these tensions and dynamics. Rather than obscuring this role, the dialectic encourages students to probe the connections between social power and “the formation of our social world and the kinds of reality we experience.” Nothing in material reality is fixed in stasis, permanent, or unchanging. The world is in a state of ceaseless motion and change, right down to the elementary particles, themselves just ripples in energy fields. Dialectical reasoning attempts to take these facts about reality seriously by understanding things within their particular contexts. It is naturally resistant to permanent rules for all cases. It understands each social phenomenon as comprising a series of underlying relationships, which are themselves always in flux.

In practical terms, if there is any hope of a revival in dialectical approaches to social problem-solving, then it will necessarily depend on the way we educate children and introduce them to our social ontology. Key to Thompson’s ideas is his theory of social ontology, our understanding of the social world—its institutions, norms, centers of power, and their workings and patterns. A resurgence of the dialectical approach he articulates has special relevance to criticisms of the education system and efforts to make it more socially productive and responsive to students. Indeed, any serious rethinking of education seems to require the maintenance of the skeptical and critical posture recommended by dialectical reasoning. While it is not the focus of the book, Thompson acknowledges the connection between his project and our attitudes about the education system: social subsystems like education can only be grasped as “embedded in broader contexts of social reality.” He argues that “understanding how schools are organized is a function of the value or purpose that the broader society places on its function.”

The model of education prevailing in the West grows out of a series of social and cultural trends, particularly during the nineteenth century, associated with the rise of nationalism and attendant efforts to centralize power and government functions. The compulsory school was critical to these efforts to construct a cohesive national identity and consolidate power in the growing nation-state. The German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762-1814), enormously influential on these social and political movements, argued in his Addresses to the German Nation that the student cannot merely be instructed, but must be deliberately fashioned—and “in such a way that he simply cannot will otherwise than you wish him to will.” The goal of the system was to create a pliable subject. The idea was to weaken and ultimately eliminate the student’s capacity to think independently or critically, to make him a vessel for the worldview, values, and material interests of government power. The school would be responsible for the creation and perpetuation of a secular religion, a kind of cult of the nation-state. The paradigm is well captured in the words of William T. Harris, U.S. Commissioner of Education from 1889 to 1906, in a lecture he gave called “The Literature of Education”:

Ninety-nine out of a hundred people in every civilized nation are automata, careful to walk in the prescribed paths, careful to follow prescribed custom. This is the result of substantial education, which, scientifically defined, is the subsumption of the individual under his species.

These ideas permeated the education movement in the United States, and the model they advanced was a rigid, authoritarian one characterized by discipline and uniformity, where the needs and interests of the student are ignored. Our society maintains a very strict order around its conceptions of learning and of what it means to be a student. This conceptual terrain is now carefully guarded, the site of enormous ruling class investment across government bodies, major corporations, and many NGOs. The federal government and global corporations know that fundamental changes in the education system could yield young adults who are insufficiently acquiescent.

Education and Cultural Reproduction

Though we are uncomfortable with discussing the social function of the system of compulsory education, it is “the largest instrument in the modern state for telling people what to do.” The task of the education system is to inculcate a framing of the world that legitimizes the ruling class. Thus, history and social studies must be taught in a way that deifies the rich and powerful and all but ignores everyone else. But even more important than the subject matter is the school environment itself; this much more than any fact or theory consumed during a lecture is what is needed to reproduce the values of the ruling class and the systems that ensue from them. This is no small thing, as human beings are naturally critical, stubborn, smart, and sensitive to injustice—they are not easily corralled into authoritarian hierarchies. And contrary to the claims of oppressive rulers since time out of mind, such hierarchies are in no way “natural.”

The system begins with the forcible, mandatory confinement of the student’s physical body, a necessary precondition for the establishment of control over her mind. The student experiences everyday life as a morose exercise in abstention, repression, and humiliation, taught to believe that knowledge is transmitted in an unquestioned one-way stream from superiors. The vital feature of compulsory schooling today is alienation: the teacher, as a member of a special priestly class, has access to the truth, which the student must receive in the prescribed manner within the walls of the school.[2] The radical tradition is brimful with incisive efforts to analogize the modern school to the prison; while these attempts have successfully demonstrated the many similarities between the school and prison as social institutions, it is time for critics of the education apparatus to reach beyond comparisons and accept that it is not merely that the school is like a prison. Rather, the school is a prison. The school calibrates the student to a state of mind and existence associated with the prison; she inhabits a “death-world,” “[a form] of social existence in which vast populations are subjected to conditions of life conferring upon them the status of living dead.”[3]

This institutional removal of the child from the household, the workplace, the city, and the public sphere more generally has catastrophic implications, both for the student and the broader society. The result is a student alienated from the processes of learning and intellectual development, a passive recipient of the dominant ideology, conditioned and destined to recreate it. The student is constructed socially not as an active participant and experimenter, but as a disembodied vehicle for an alien ideology—alien in the sense that the ideology does not reflect, but actively suppresses, the needs, desires, and values of the student. The training the student receives is training in unthinking compliance and in practical strategies for avoiding the discomfort that accompanies critical challenges to power. The primary goal of the school system is not to present arguments in favor of the status quo, or even to contradict through propaganda the claims of its critics, but to foreclose the possibility of argument itself by satisfying the student that no successful alternative to the status quo exists in the record or could exist in principle.

Education cannot mean merely preparing our children to recreate the ideologies and injustices of this system. The only legitimate remit of a system of education is to give children the tools to think critically about the natural and social world. Nothing can be placed beyond questioning, not even the institutional pillars of our own time and place. Dialectical thinking encourages students to adopt other perspectives and to challenge their own ideas by exploring the complex, internally contradictory nature of observed phenomena. Such a learning environment yields adults who approach society with an understanding of their own values rather than with trained skill in repeating the ideas and values of those in power. If we educate children to shore up ruling class power, we cannot hope to reclaim independence and autonomy as cultural values. When the dialectical process stops, inquiry comes to a dead end in concepts and institutions treated as unchallengeable and unalterable; this is reification at work.

Allowing dialectics into our approach to children and to pedagogy brings an openness that extends to other ways of life. New fields of possibility are opened to them; they are not beholden to particular worldview, religions, or ideologies. Thus a dialectical approach to education undermines the fundamental preconditions and standards of cultural reproduction. It gives society resilience because it teaches students to reflect on society anew and attend to injustices in real time. It threatens the ruling class, because the curious, self-respecting student cannot be expected to accept the answers we’ve so dutifully accepted. We also know that there are deep, measurable connections between student reports of mindfulness and unscripted experiences in adult society and in nature. In this mode of learning, the student is no longer the mere audience of a person in a position of authority; she is a participant in an improvisation, where the absorption of new information and the development of understanding are extemporaneous—and thus felt and remembered. As our ability to address these connections becomes more rigorous scientifically, anarchists’ ideas on education are increasingly vindicated.

Alternative Models of Education

Radically anti-authoritarian education reformers have built alternatives to the dominant system alongside it and within its cracks. Whether they acknowledged it or said so explicitly, these anarchists and deschoolers were motivated by and encouraging a dialectical way of thinking. Anarchists in particular have centered the lives, experiences, and wellbeing of children in a way other movements have not, recognizing that the adult-child gap may be the deepest privilege divide in society. That important thinkers in the anarchist movement have taken such a keen interest in education says much about the anarchist worldview; among these thinkers, Colin Ward (1924-2010) stands out as presenting a bold and exciting criticism of education that reflects Thompson’s worries about the contemporary atrophy of critical thinking. Many of Ward’s most lasting contributions to the cultural dialogues on early education and the experiences of children are set forth in his 1978 book, The Child in the City. The book contends that “we have accepted the exclusion of children from real responsibilities and real functions in the life of the city,” condemning them to institutions and physical spaces that are unwelcoming and dangerous to them. In the prevailing model of education, obedience is the expectation, as students are prepared for successive rounds of standardized tests by rigid government-prescribed curricula. The school as we know it doesn’t take the child seriously as a fellow human being—its fundamental goals are incompatible with the dignity and autonomy of the child. Among the major social functions of the modern school is to preempt the child as an autonomous actor and creative force capable of imagining alternatives to the status quo. Part of Ward’s genius is that he attempts to adopt the perspective of the child; he has radical ideas about education and pedagogy because he has radical ideas about how society should conceptualize and honor children and childhood. Ward’s was a pragmatic and ecumenical anarchism informed by his observations of and respect for real-life liberatory practice—a “constructive antinomianism,” as one historian put it. Ward was notably much more comfortable than most of today’s mainstream with children engaging in productive work, and he believed that we should “make the whole environment accessible to them.” He held to the radical notion that if we want to help children grow into happy, socially competent, productive members of a healthy community, we must permit them more space within that community. “In the ideal city,” he wrote, “every school would be a productive workshop and every workshop an effective school.” Ward’s comfort and indeed enthusiasm for the employment of children should not be interpreted as an endorsement of full-time work for children. Quite to the contrary, he thought that they should spend most of their time engaged in free play and exploration. Confronted with the outside world—in particular, the natural world—students report more awe and excitement around learning, more sustained and authentic engagement, and better overall mental health. They are more likely to meet life’s challenges as puzzles to be solved and interesting opportunities to hone their skills. They appreciate that all patterns in nature are temporary. For these reasons, Ward’s vision was “schools without walls,” where the student is fully immersed in the broader social order.

The literary titan Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910), an anarchist fellow traveler, was also deeply interested in building functional prototypes of new educational and pedagogical programs. An understanding of his approach to education requires a look at his worldview and motivating values. Part of what makes Tolstoy’s novels so captivating, heartfelt, and authentically human is his deep social criticism. But it is a criticism contained in Tolstoy’s unique ability to look at powerful institutions—social, economic, religious—in all of their many absurdities and contradictions. In Tolstoy, we find powerful leaders who are petty and misguided, driven by selfishness and vanity rather than commitment to the common good. His characters must try to appease various powerful and predatory institutions, and their best efforts often lead to puzzling, frustrating results. We identify with them both because Tolstoy paints them in fine detail, and because we still have to appease many of the same gods, even if their shapes have changed since his time.

Tolstoy’s political ideas are extremely radical, even by today’s standards. His non-resistance philosophy, much like that of the American abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison (from whom he quotes at length in his The Kingdom of God Is Within You), does “not acknowledge allegiance to any human government” and opposes all uses of force, including even self-defense. Non-resistants like Garrison and Tolstoy abstained from voting and running for office; they refused to fight in wars or pledge loyalty to any state. They were devout Christians, but they held to a truer if more controversial picture of Jesus—as a deeply counter-cultural figure who infuriated the ruling classes by showing their self-contradictions. Like the historical Jesus, Tolstoy did not try to hide his contempt for the status quo.

Tolstoy saw education as an innate need to be met, with the adults helping to serve that need rather than dominating and punishing children. His approach to education put the students in the position of highest importance, their curiosities and interests driving the subject matter and process. Of a visit to a school in Germany, he wrote in his diary, “I was at school. Terrible. Prayer for the king, beatings. Everything by heart. Frightened, mutilated children.” He knew he had to try to formulate the child, education, and the school in a different, more socially responsible way. In 1862, describing the daily workings of his school, Tolstoy wrote,

They [the students] bring nothing with them no books and no copy-books. They are not required to study their lessons at home. Not only do they bring nothing in their hands, but nothing in their heads either. The scholar is not obliged to remember to-day anything he may have learned the evening before. The thought about his approaching lesson does not disturb him. He brings only himself, his receptive nature, and the conviction that school to-day will be just as jolly as it was the day before.

Tolstoy was an aristocrat, and for that reason, locals met his school with a level of mistrust, frequently well justified by lessons learned in interactions with predatory elites. He recalls the fear among parents that students “will be bundled into carts and carried off to Moscow.” This also reflects parents’ fears about the coincidence of interests between the education establishment and the government and military apparatus.

We hear echoes of Tolstoy’s remarkable libertarian voice in Emma Goldman (1869-1940), another anti-authoritarian defender of children and radical opponent of government education. In her essay “The Child and Its Enemies,” published in her anarchist journal Mother Earth in 1906, the first year of its publication, Goldman offers a radical alternative to the dominant institutional approach to education and the child’s education and development generally. Goldman believed that “every effort in our educational life seems to be directed toward making of the child a being foreign to itself,” and that this self-denial and alienation led to social strife and antagonism. She anticipates later anarchists and radical critics of the state’s education system in seeing its primary goal and purpose as the creation of an unthinking, obedient conformist, “a patient work slave, professional automaton, tax-paying citizen, or righteous moralist.” Goodman argued that we should experiment with “different kinds of school” or “no school at open,” opening ourselves to a range of models including children and young people in everything from “practical apprenticeships” and community service to farm schools and the arts. Instead, he points out, we have seen sustained attacks on progressive educational models and adherence to the “mass belief” and “superstition” of the traditional, one-size-fits-all school.

Such radical visions of education open the way for a revival of a dialectical project to reincorporate critical thinking and serious challenges to increasingly oppressive cybernetic capitalism. Without a capacity to frame challenges to “our own beliefs and normative structures of thought,” in Thompson’s words, we are doomed to reproduce a destructive and manipulative system of intense alienation. Engagement with dialectical thought allows us to “free ourselves from pre-metabolized forms of meaning,” opening space for genuine creativity and liberatory practice. The school must be a key site for such critical interventions.

Notes.

[1] If Thompson exaggerates here, his point is nonetheless valuable: “Corporate CEOs are now indistinguishable from those who work for them as well as those who serve them. All dress in standard street clothes, faces pierced with all forms of steely accoutrements, tattoos abound just as the dyed hair screaming for attentiveness from the depths of existential anonymity and a regressive adolescence takes hold of the self in what [W.H.] Auden refers to as our ‘jackass age.’”

[2] In Anarchy in Action, Ward writes, “Bakunin made the same comparison as is made today by Everett Reimer and Ivan Illich between the teaching profession and a priestly caste, and he declared that ‘Like conditions, like causes, always produce like effects. It will, then, be the same with the professors of the modern school, divinely inspired and licensed by the State. They will necessarily become, some without knowing it, others with full knowledge of the cause, teachers of the doctrine of popular sacrifice to the power of the State and to the profit of the privileged classes.’”

[3] Nicholas Fesette, “Carceral Space-Times and The House That Herman Built” in Soyica Diggs Colbert, Douglas A. Jones Jr., Shane Vogel, eds., Race and Performance after Repetition (Duke University Press 2020).