Grenfell: the avoidable tragedy

Alice Johnson, IBA Multimedia Journalist

INTERNATIONAL BAR ASSOCIATION

Monday 18 November 2024

The burnt out remains of the Grenfell apartment tower are seen in North Kensington, London, Britain, 18 June 2017. REUTERS/Neil Hall

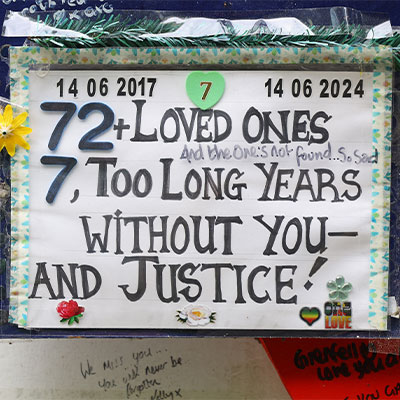

Seven years on from the tragedy that saw 72 avoidable deaths, the judge-led inquiry has completed its reports. Global Insight assesses what went wrong, the lessons learnt and what needs to change.

Just before 1am on 14 June 2017, a fridge-freezer on the fourth floor of a 1950s-style council block in one of London’s wealthiest boroughs caught fire. Within minutes a blaze broke out through the kitchen window and ripped through the exterior of the building, quickly spreading into the homes of residents on higher floors. As a result, 72 people, including 18 children, died. The chair of a public inquiry into the disaster has since describe the deaths as ‘avoidable’.

The Grenfell Tower fire devastated a local community and left many unanswered questions. Theresa May, the then-prime minister, ordered a public inquiry into the disaster, led by retired Court of Appeal judge Sir Martin Moore-Bick, to examine its causes and the failings that turned a small flat fire into an inferno. Seven years after the UK government announced the inquiry its second and final report was published in September.

Whenever there’s a clash between corporate interest and public safety, governments have done everything they can to avoid their responsibilities to keep people safe

Grenfell United

Advocacy group for the families of victims

Grenfell United, an advocacy group made up of the families of victims and survivors of the fire, said in a statement that the report is ‘a significant chapter in the journey to truth, justice and change’ but that justice has not yet been delivered. ‘The inquiry report reveals that whenever there’s a clash between corporate interest and public safety, governments have done everything they can to avoid their responsibilities to keep people safe’, the group said. ‘The system isn’t broken, it was built this way.’

Seven years on, the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) is yet to make any charging decisions, and any trials are not expected until 2027.

Striking human rights impacts

The findings in the report are stark and raise serious human rights concerns that have already been identified in the events surrounding the fire. In 2019, the Equality and Human Rights Commission found – following a separate inquiry into the disaster – that the government and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea had violated the right to adequate housing and rights to life of residents, including by allowing Grenfell Tower to be wrapped in highly combustible materials and failing to make reasonable adjustments for the disabled and vulnerable groups, such as pregnant women and children, to escape in the event of an emergency. About 40 per cent of the building’s disabled or vulnerable residents died in the fire.

Human rights impacts do not explicitly feature in the limited scope Moore-Bick chose for the public inquiry, yet the report tells a story of decades of government indifference towards fire safety and a social housing system that ignored repeated complaints from residents about fire risks and ‘lost sight of the fact that the residents were people who depended on it for a safe and decent home and the privacy and dignity that a home should provide’.

Person views dedications and messages on a wall of condolences near to the covered remains of Grenfell Tower, on the day of the publication of the second report of the UK public inquiry into the deadly 2017 Grenfell fire, in London, 4 September 2024. REUTERS/Toby Melville

Aoife Nolan, Professor of International Human Rights Law and Director of the University of Nottingham Human Rights Law Centre, says that despite the report not engaging with the language of human rights directly, breaches of the right to life, adequate housing and equality in the events surrounding the fire are obvious. ‘The human rights impacts are wide ranging […] you can take the report findings and map them straight on to a human rights framework and identify clear problems there’, she says.

In 2018 the then-UN Special Rapporteur on the right to adequate housing, Leilani Farha, visited the UK to meet the Grenfell community. She expressed concerns that the government may have breached international human rights standards on housing safety, and this could have been a factor in the outbreak of the fire. She asked the government to formally participate in the inquiry but was rejected.

Farha says it’s unfortunate that the UK government decided against using a human rights framework for the inquiry because it fits ‘squarely’ with understanding the events surrounding the fire and how to prevent similar horrors from occurring. ‘The final report is a thorough exposé of what happens when a system fails to take seriously the human right to housing’, she says.

Mark Stephens CBE, Co-Chair of the IBA Human Rights Institute, says that historically, public and commercial landlords haven’t thought about the human rights of residents when providing homes. He says the report may change behaviour but that the cost of raising standards will ultimately be passed down to the consumer.

In the report Moore-Bick describes the council’s immediate response to the fire as ‘muddled, slow’ with certain aspects demonstrating a ‘lack of respect for human decency and dignity’ with many feeling ‘abandoned by authority and utterly helpless’. Survivors and the bereaved weren’t told where to go on the night of the fire and many were placed in hotel rooms wholly unsuitable for them with no assurance about how long they could stay. A family of five was forced to stay in a room with only a double bed and some were distressingly placed on high floors.

Muslims could not access Halal food and people with particular social or religious needs suffered ‘a significant degree of discrimination’, Moore-Bick says. The inquiry, blaming time pressures, did not examine questions of potential discrimination in social housing policy, however. Despite submissions from lawyers acting for survivors and the bereaved stating that racism may have had a role in why a disproportionate amount of people who lived and therefore died in the Tower were from ethnic minority groups.

Imran Khan KC, who made such submissions, believes the inquiry let victims down by failing to examine whether prejudice towards race, class or disability caused residents to be placed in inadequate homes and impacted their treatment on the night of the fire. ‘When the inquiry started what we wanted them to look at is how it came to be that, in this rich country, this rich borough, there appeared to be a systemic problem in terms of discrimination’, he says.

The possibility of there being another Grenfell is there because there will be bad buildings, there will be people who will cut corners

Imran Khan KC

Khan believes that the inquiry missed a real opportunity to ensure a similar disaster to Grenfell never happens again. ‘The possibility of there being another Grenfell is there because there will be bad buildings, there will be people who will cut corners, and the people who will end up in the buildings will be people who are poorer and from different social backgrounds.’

Profit before people

The inquiry report paints a damning picture of a fraudulent and irresponsible construction industry, inadequately policed and enabled by a government that prioritised commercial interests over public safety. Moore-Bick says the companies that manufactured the deadly cladding and insulation used to refurbish Grenfell Tower before the fire engaged in ‘deliberate and sustained strategies to manipulate the testing process, misrepresent test data and mislead the market’.

Michael Mansfield KC, a human rights barrister who represents bereaved families affected by the fire, says that the anti-red tape agenda between 2010 and 2016 created an environment where corporate wrongdoing could flourish. ‘It was a situation in which respect of basic human rights were lost in a quagmire of profit before people’, he says.

Moore-Bick says in the report that decades before the Grenfell fire, the UK government had many opportunities to address the risks associated with combustible cladding. From 2010 onwards, wholesale deregulation – which aimed to boost economic growth – created an environment in which urgent fire safety matters were pushed aside. Moore-Bick says the government resisted repeated calls from the fire sector to amend inadequate building and fire safety rules while pushing a ‘one in, one out’ policy regarding regulations, later extended to ‘one in, three out’, to slash red tape for businesses.

Moore-Bick found that three manufacturing companies – Arconic, Celotex and Kingspan – exploited weak regulations to sell products for the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower that they knew were highly dangerous. He says they succeeded largely because safety inspectors and regulators were incompetent and more interested in keeping the companies as customers than holding them to account. The Building Research Establishment and British Board of Agrément – both private bodies – are heavily criticised in the report for prioritising commercial interests over independence and rigour. This resulted in the testing and certification of products later used on Grenfell Tower that were misleading and provided a false sense of security.

‘With Grenfell it’s hard to think of something that went right’, says Emma Hynes, a barrister specialising in construction matters who was counsel to the inquiry. ‘Everything in the building failed.’

Moore-Bick found that the plastic-filled cladding panels supplied by Arconic – which behaved like lighter fuel on the walls – were the main cause of the rapid fire spread. Hynes says she struggles to have sympathy for the manufacturers that sold materials they knew were life-threatening. ‘For them to put their products on the market as they did and to this day some of them hold their hands up and say: “don’t look at us, you all knew about this […]”; for me that is the most reprehensible thing.’

Shona Frame, a construction lawyer and Education Officer for the IBA Energy, Environment, Natural Resources and Infrastructure Law Section, says that since the Building Safety Act was introduced in 2022 to raise standards following the Grenfell fire, she has seen an enormous number of claims made against contractors, designers and others for historic fire safety defects. The Act allows parties to make claims for issues that occurred up to 30 years ago.

Hynes believes the Building Safety Act 2022 and changes to fire regulations since the Grenfell fire don’t go far enough in closing gaps and loopholes in the law for unscrupulous manufacturers. ‘It seems to me the most reprehensible are the manufacturers and although there are substantial rules coming in regarding construction products and how they should be regulated and managed, I don’t think it goes far enough’, she says.

Moore-Bick noted in the report that Approved Document B – statutory guidance for the construction industry on compliance with building regulations, including fire safety – still contains confusing language and doesn't provide the information needed to ensure that buildings are fire-safe.

The businesses named in the report have denied wrongdoing in relation to the fire. Arconic says its cladding was ‘legal to sell in the UK’ and rejects any claim it sold unsafe product. Celotex, who made most of the building’s insulation, says the cladding system described in its marketing literature for the use of its materials met safety requirements and was ‘substantially different to that used at Grenfell Tower’. Kingspan says it made about five per cent of the insulation and that its ‘historical failings’ were ‘not found to be causative of the tragedy’.

Moore-Bick says the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation (TMO) – the social landlord of Grenfell residents – was motivated by cost-cutting during the refurbishment and didn’t pay enough attention to fire safety. The report describes the TMO as having a ‘persistent indifference to fire safety, particularly the safety of vulnerable people’ and was considered by residents as a ‘bullying overlord that belittled and marginalised them’. Moore-Bick says the TMO ignored repeated complaints from residents and the London Fire Brigade about fire hazards within the building.

Mansfield says one tenant had warned the council about serious fire safety concerns a decade before the fire. ‘When they left the building that night, there were no contingency plans or fire drills’, he says. ‘Once you start thinking about it as a human right you begin to see how significant it really is.’

Dedications and messages are seen on a wall of condolences near to the covered remains of Grenfell Tower, on the day of the publication of the second report of the UK public inquiry into the deadly 2017 Grenfell fire, in London, 4 September 2024. REUTERS/Toby Melville

The TMO – which no longer controls housing in the borough – said in a statement that it accepts the inquiry’s findings and is ‘deeply sorry’ for its role.

Moore-Bick also points out the shortcomings of the architect and building contractors involved in the Grenfell Tower refurbishment, accusing them of failing to check if materials used complied with regulations and being more concerned with cost than fire safety. ‘Everyone involved in the choice of the materials to be used in the external wall thought that responsibility for their suitability and safety lay with someone else’, he says.

Fifty-eight recommendations for change

The second and final inquiry report into the Grenfell Tower fire includes 58 recommendations for the construction industry, professionals and the government to prevent a similar disaster from happening again. The UK government said in September it would respond to the proposals within six months.

Moore-Bick outlines a clear framework for improving building safety and oversight of the government and construction industry. He describes the regulatory landscape at the time of the fire as ‘too complex and fragmented’. He says that the government should introduce a single independent body to regulate the construction industry which reports directly to the Secretary of State.

Frame says that a single regulator would be more efficient but require a huge surge in resources from the government. ‘The architecture for this organisation doesn’t exist, so there is an enormous task to be undertaken to put the structures in place in order to implement this’, she says.

Moore-Bick also wants the government to drive up fire safety standards by widening the definition of high-risk buildings in the Building Safety Act 2022 and amending Approved Document B to make it easier to understand. Further recommendations include a mandatory accreditation for fire risk assessors, a licencing regime for contractors and compulsory fire safety strategies for high-risk buildings.

Roberta Downey, Head of Vinson & Elkins’ International Construction Group, welcomes the recommendations but says that the UK government will need to carefully balance improving standards with the high cost of building safer homes. ‘I welcome of course the increasing qualifications required of people who are dealing with delivering high risk building developments and better regulation of supervision […] but I’m also realistic: if the regulation is too tight or too bureaucratic then there is a risk of disincentivising much and urgently needed affordable housing’, says Downey, who is also Co-Chair of the IBA Innovations Subcommittee of the IBA International Construction Projects Committee. ‘For example, fewer people actually wanting to apply for the licences to build these projects, the cost of them increases etc so projects don’t get built.’

The UK government has pledged to build 1.5 million affordable houses in the next five years. In a speech responding to the final inquiry report Prime Minister Keir Starmer issued an apology on behalf of the British state and said the homes his government has promised will be ‘safe, secure and built to the highest standards’.

In the final report, Moore-Bick also proposes better training and equipment for fire services and that the government further considers personal emergency evacuation plans for vulnerable people. Another recommendation is that the government is required to maintain a publicly accessible record of its progress in implementing recommendations from inquiries, committees or coroners, and detailed reasons for rejecting any of those recommendations.

Hynes says forcing the government to record its progress on implementing the recommendations would help significantly with holding elected officials accountable. ‘It is owed to them [the Grenfell community] that at least these recommendations are considered and if they are rejected, they are rejected in a transparent way; not rejected because large companies have a big voice in government’, she says.

Following the publication of the report the UK government agreed to a separate request from Grenfell United to ban the manufacturing companies accused of selling the deadly materials found on Grenfell Tower from receiving government contracts.

The history of regulation is the history of disaster

Emma Hynes

Counsel to the inquiry

Hynes worries, however, that there is a lack of strategic thinking by the UK government about building safety in general and what might be the next big danger. ‘The history of regulation is the history of disaster, and it may take a disaster or a near disaster for us to work out what the next one is’, she says.

Mansfield KC says that beyond the recommendations of the report there is still so much more for UK governments to do to prioritise public safety. He says a recent fire at a block of flats in Dagenham in August – a building that was still in the process of having its dangerous cladding removed – shows that the government still isn’t taking the human rights of residents seriously enough. ‘That principle still hasn’t hit the deck’, he says.

Following the Grenfell fire, the government announced a building safety programme including grants for the removal of dangerous cladding systems on high-rise residential buildings. A report published by the National Audit Office in November said up to 60 per cent of buildings in England with dangerous cladding have yet to be identified, while of the 4,771 buildings that had been identified, work had started on only half of them. The watchdog said the government isn’t on track to meet its target of removing all dangerous cladding by 2035.

Mansfield also believes that the seven-year long inquiry has delayed prosecution efforts against suspected culpable parties. The Metropolitan Police said in September it would need a further 12 to 18 months to examine the report ‘line by line’ before it can file evidence with the CPS. ‘You can order an inquiry to soft peddle, so it doesn’t prejudice the prosecution’, Mansfield KC says. ‘Police should have done the prosecution first and the inquiry should have been soft peddled.’

Khan says that what his clients want the most is somebody being held to account in a courtroom for the disaster. He says he doesn’t think the government is going to implement the recommendations. ‘I know that because there is a history of it and I’ve been here before’, he says. Khan acted for the family of Stephen Lawrence – a Black teenager killed in a racist attack by a gang of white men in 1993 – in the public inquiry into his murder. ‘With the final report you assume it is going to change society forever because you’ve spent a fortune and time and effort on it, but it doesn’t’, he says.

Khan believes the main benefit of public inquiries is that they change people’s perspectives on an issue. ‘Everyone knows Grenfell is shorthand for my building is unsafe; it empowers civil society and that I think is going to be a longer legacy than the recommendations.’

Alice Johnson is the IBA Multimedia Journalist and can be contacted at alice.johnson@int-bar.org