The Return of Odysseus to Ithaca

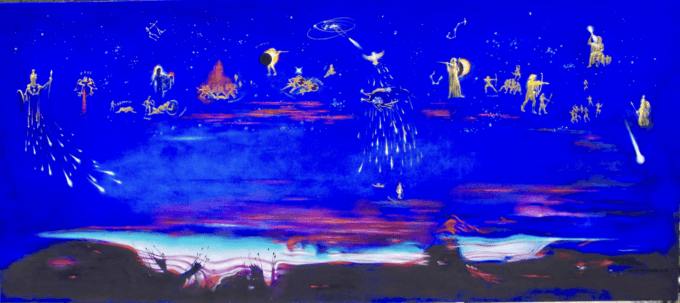

The Trojan War by Evi Sarantea. Astronomical phenomena during the Trojan War. In the first half of the image, starting from left, we see the death of Patroklos by Hector and the death of Hector by Achilles. At the remaining painting we see the Odysseus in Ithaca killing the suitors during an eclipse of the Sun (Odyssey 20.356-357).

Prologue

Homer and his epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are fundamental to Greek history, mythology and civilization. Homer lived during the Bronze Age, and, most likely, during late thirteenth or late twelfth century BCE. The stories Homer sings are about the Trojan War (the Iliad) and about the return of Odysseus to his home, Ithaca, (the Odyssey). But these stories include insights about the Cosmos, cosmology, science, technology, politics, geography, the gods, athletics, adventures, heroism, farming, the beautiful day of return to Ithaca (Νόστιμον ήμαρ), and Nostos (νόστος), the passionate effort and struggles to return home. In addition, the Odyssey says a lot about the love of Odysseus for his wife Penelope and son Telemachos. Odysseus even turned down Calypso’s promise of immortality in order to return home to Penelope.

Homer: the teacher of the Greeks

The immense richness of Homer made him the teacher of the Greeks, their greatest poet and philosopher. Rhapsodes, singers of tales, sang extensive sections of the epics in sixth century BCE Athens and other cities. Greek children learned Greek from Homer. The great poets of the fifth century BCE (Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes) were inspired by Homer’s stories and wrote masterpieces for the theater of Dionysos. Aristotle edited the epics of Homer for his pupil Alexander the Great. Scholars in the Library of Alexandria in the third century BCE gave the epics the form they have today, each divided in 24 chapters / books. And the Roman Emperor Hadrian asked the Oracle of Apollo at Delphi about Homer and Pythia, priestess of Apollo, said that Homer was the son of Telemachos and Polykaste,[1] daughter of King Nestor of Pylos, Peloponnesos. Nestor was a colleague of Odysseus and a great hero of the Troyan War. This explains the detailed knowledge in the epics on heroes, places, gods, science and Greek culture. That is also the reason the epics became the greatest stories ever told in Greek and world literature. They survived barbarian invasions of Greece and the Christianization of Hellas. In fact, despite the 1082 Christian anathema of Hellenism,[2] Christian scholars like Ioannes Tzetzes (c. 1110-1180) and Eustathios (c. 1115-1195), archbishop of Thessalonike, loved Homer. Tzetzes wrote “Allegories of the Iliad.” Tzetzes wrote his allegorized Homer in the 1140s or 1150s. He dedicated it to “the most powerful and most Homeric queen, Lady Eirene of the Germans.” Queen Eirene was none other than Bertha von Sulzbach of Bavaria who came to Constantinople in 1142 to marry Manuel I Komnenos. Manuel I reigned from 1143 to 1180. And archbishop Eustathios also edited the epics of Homer and left extensive commentaries on Homer.[3] Both Tzetzes and Eustathios used allegories to diminish or make invisible the gods in Homer, a tradition that continues to some degree to this day among monotheist scholars and theologians. In fact, since WWII, several modern commentators on Homer “study” Homer to degrade him and the Greeks. They say Homer did not exist and his epics are fiction.

This decline mirrors a general decline of Western civilization and the weaponization of nearly everything. In the case of Homer, even films on the immortal Homeric epics, sanitize both the text and the gods.

The Return

The 2024 film on “The Return [of Odysseus to Ithaca]” mirrors the fear and power of cinematographers. The producers of the 2024 film did not read the Odyssey carefully. They ignored the Trojan War and the struggles of Odysseus to return home to Ithaca.

The film begins with Odysseus sprawled on an unknown beach, nearly dead. Then we see a very old-looking Odysseus finding his way to his own land where his swineherd Eumaeus takes him in and gives him food. But neither Odysseus nor the swineherd recognize each other. However, Odysseus sees his old dog Argos on heaps of manure and the 20-year old faithful Argos recognizes Odysseus, moves his ears and tail, and dies. Eumaeus observes the dog and Odysseus petting him and suspects his guest is Odysseus. On his part, Odysseus is tight-lipped to a disturbing extent. His own son Telemachos is hostile towards him, refusing to accept Odysseus as father. At the same time, Telemachos is threatened by the suitors courting his mother. Penelope follows to some degree the Homeric script of making and unmaking a woolen coat for Laertes, father of Odysseus, who does not appear in the film. The other person who recognizes Odysseus is his nanny, Eurycleia. She was washing his legs when she recognized a scar from hunting a boar when Odysseus was a young man. Odysseus stopped Eurycleia from expressing her joy.

Odysseus wanted to kill his wife’s suitors who had turned his palace into a perpetual eating and wrestling ground. That moment arrived when Penelope brought Odysseus’ bow and said to the men courting her that she would choose as her husband the man who could string the bow and shoot an arrow through 12 axe shafts. No one of the suitors was strong enough to match the strength and skills of Odysseus, save for Odysseus himself camouflaged like a beggar. The film producers even put Telemachos as one of the suitors trying to string his father’s bow. This was a very offensive misreading of Homer, an opportunity for a suitor to accuse Telemachos of scheming to marry his own mother. Finally, Odysseus grabs the bow and effortlessly strings it and shoots an arrow through the 12 axe shafts and, immediately, starts killing the suitors. At that moment, Telemachos joins him in finishing the orgy of the suitors. Eventually Penelope realizes that the beggar was Odysseus and the two, Odysseus and Penelope, come together after 20 years separation. The war was over. Odysseus was finally home to Ithaca with Penelope and Telemachos and his old father Laertes.

Sanitizing Homer

The film producers made up Telemachos behaving like a barbarian. By ignoring the dangerous struggles of Odysseus and his leading role in the conquest of Troy, and by ignoring goddess Athena that guided Odysseus, they diminished Homer and the heroism and humanity of Odysseus. And by filming the story in a place with British medieval architecture, they insulted the audience.

Despite these defects, overlooking the gods and other crucial details of the Odyssey of Homer, “The Return” succeeded portraying Odysseus and Penelope as the Homeric heroes they were. The protagonists, Ralph Fiennes (Odysseus) and Juliette Binoche (Penelope), were outstanding in expressing the tragedy that, pretty much, engulphed their lives. Virtues like love between husband and wife, passion to return home, and the importance of the family triumphed.

1. Anthologia Palatina 14.102. ↑

2. N. G. Wilson, Scholars of Byzantium, revised edition (Cambridge, MA: Medieval Academy of America, 1996) 154. ↑

3. Eric Cullhed, ed., Eustathios of Thessalonike Commentaries on the Odyssey Rhapsodies A-B (Uppsala University Press, 2016). ↑