New version of Earth model captures detailed climate dynamics

Earth supports a breathtaking range of geographies, ecosystems and environments, each of which harbors an equally impressive array of weather patterns and events. Climate is an aggregate of all these events averaged over a specific span of time for a particular region. Looking at the big picture, Earth's climate just ended the decade on a high note—although not the type one might celebrate.

In January, several leading U.S. and European science agencies reported 2019 as the second-hottest year on record, closing out the hottest decade. July went down as the hottest month ever recorded.

Using new high-resolution models developed through the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Office of Science, researchers are trying to predict these kinds of trends for the near future and into the next century; hoping to provide the scientific basis to help mitigate the effects of extreme climate on energy, infrastructure and agriculture, among other essential services required to keep civilization moving forward.

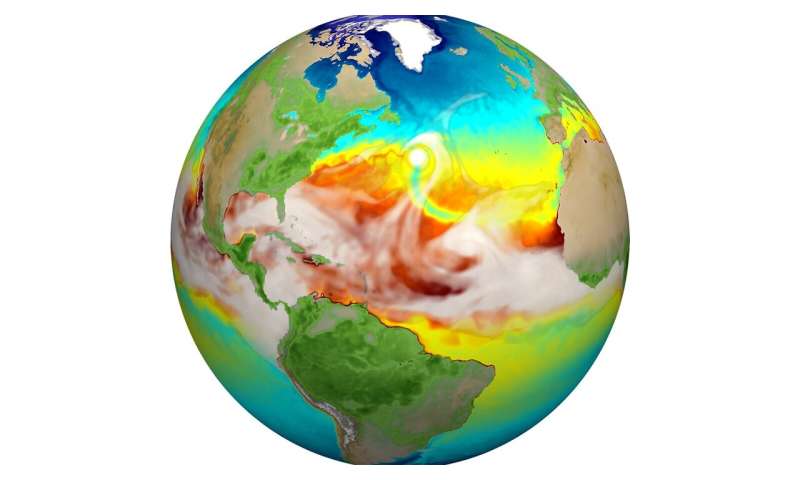

Seven DOE national laboratories, including Argonne National Laboratory, are among a larger collaboration working to advance a high-resolution version of the Energy Exascale Earth System Model (E3SM). The simulations they developed can capture the most detailed dynamics of climate-generating behavior, from the transport of heat through ocean eddies—advection—to the formation of storms in the atmosphere.

"E3SM is an Earth system model designed to simulate how the combinations of temperature, winds, precipitation patterns, ocean currents and land surface type can influence regional climate and built infrastructure on local, regional and global scales," explains Robert Jacob, Argonne's E3SM lead and climate scientist in its Environmental Science division. "More importantly, being able to predict how changes in climate and water cycling respond to increasing carbon dioxide (CO2) is extremely important in planning for our future."

"Climate change can also have big impacts on our need and ability to produce energy, manage water supplies and anticipate impacts on agriculture" he adds, "so DOE wants a prediction model that can describe climate changes with enough detail to help decision-makers."

Facilities along our coasts are vulnerable to sea level rise caused, in part, by rapid glacier melts, and many energy outages are the result of extreme weather and the precarious conditions it can create. For example, 2019's historically heavy rainfalls caused damaging floods in the central and southern states, and hot, dry conditions in Alaska and California resulted in massive wild fires.

And then there is Australia.

To understand how all of Earth's components work in tandem to create these wild and varied conditions, E3SM divides the world into thousands of interdependent grid cells—86,400 for the atmosphere to be exact. These account for most major terrestrial features from "the bottom of the ocean to nearly the top of the atmosphere," collaboration members wrote in a recent article published in the Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems.

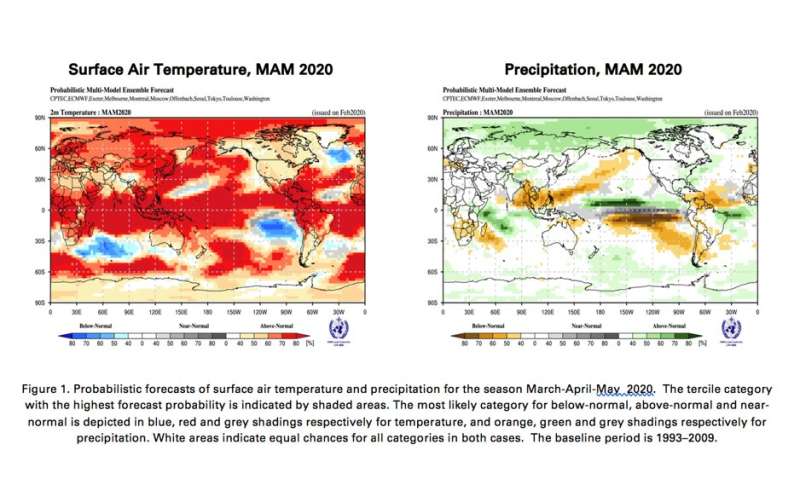

"The globe is modeled as a group of cells with 25 kilometers between grid centers horizontally or a quarter of a degree of latitude resolution," says Azamat Mametjanov, an application performance engineer in Argonne's Mathematics and Computer Science division. "Historically, spatial resolution has been much coarser, at one degree or about 100 kilometers. So we've increased the resolution by a factor of four in each direction. We are starting to better resolve the phenomena that energy industries worry about most—extreme weather."

Researchers believe that E3SM's higher-resolution capabilities will allow researchers to resolve geophysical features like hurricanes and mountain snowpack that prove less clear in other models. One of the biggest improvements to the E3SM model was sea surface temperature and sea ice in the North Atlantic Ocean, specifically, the Labrador Sea, which required an accurate accounting of air and water flow.

"This is an important oceanic region in which lower-resolution models tend to represent too much sea ice coverage," Jacob explains. "This additional sea ice cools the atmosphere above it and degrades our predictions in that area and also downstream."

Increasing the resolution also helped resolve the ocean currents more accurately, which helped make the Labrador Sea conditions correspond with observations from satellites and ships, as well as making better predictions of the Gulf Stream.

Another distinguishing characteristic of the model, says Mametjanov, is its ability to run over multiple decades. While many models can run at even higher resolution, they can run only from five to 10 years at most. Because it uses the ultra-fast DOE supercomputers, the 25-km E3SM model ran a course of 50 years.

Eventually, the team wants to run 100 years at a time, interested mainly in the climate around 2100, which is a standard end date used for simulations of future climate.

Higher resolution and longer time sequences aside, running such a model is not without its difficulties. It is a highly complex process.

For each of the 86,400 cells related to the atmosphere, researchers run dozens of algebraic operations that correspond to some meteorological processes, such as calculating wind speed, atmospheric pressure, temperature, moisture or the amount of localized heating contributed by sunlight and condensation, to name just a few.

"And then we have to do it thousands of times a day," says Jacob. "Adding more resolution makes the computation slower; it makes it harder to find the computer time to run it and check the results. The 50-year simulation that we looked at in this paper took about a year in real time to run."

Another dynamic for which researchers must adjust their model is called forcing, which refers mainly to the natural and anthropogenic drivers that can either stabilize or push the climate into different directions. The main forcing on the climate system is the sun, which stays relatively constant, notes Jacob. But throughout the 20th century, there have been increases in other external factors, such as CO2 and a variety of aerosols, from sea-spray to volcanic.

For this first simulation, the team was not so much probing a specific stretch of time as working on the model's stability, so they chose a forcing that represents conditions during the 1950s. The date was a compromise between preindustrial conditions used in low-resolution simulations and the onset of the more dramatic anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions and warming that would come to a head in this century.

Eventually, the model will integrate current forcing values to help scientists further understand how the global climate system will change as those values increase, says Jacob.

"While we have some understanding, we really need more information—as do the public and energy producers—so we can see what's going to happen at regional scales," he adds. "And to answer that, you need models that have more resolution."

One of the overall goals of the project has been to improve performance of the E3SM on DOE supercomputers like the Argonne Leadership Computing Facility's Theta, which proved the primary workhorse for the project. But as computer architectures change with an eye toward exascale computing, next steps for the project include porting the models to GPUs.

"As the resolution increases using exascale machines, it will become possible to use E3SM to resolve droughts and hurricane trends, which develop over multiple years," says Mametjanov.

"Weather models can resolve some of these, but at most for about 10 days. So there is still a gap between weather models and climate models and, using E3SM, we are trying to close that gap."

The E3SM collaboration's article, "The DOE E3SM Coupled Model Version 1: Description and Results at High Resolution," appeared in the December 2019 issue of Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems.

More information: Peter M. Caldwell et al. The DOE E3SM Coupled Model Version 1: Description and Results at High Resolution, Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems (2019). DOI: 10.1029/2019MS001870