Riding the wave of a supernova to go interstellar

When it comes to the challenges posed by interstellar travel, there are no easy answers. The distances are immense, the amount of energy needed to make the journey is tremendous, and the time scales involved are (no pun!) astronomical. But what if there was a way to travel between stars using ships that take advantage of natural phenomena to reach relativistic velocities (a fraction of the speed of light)?

Already, scientists have identified situations in which objects in the universe are able to do this—including hypervelocity stars and meteors accelerated by supernovae explosions. Delving into this further, Harvard professors Manasvi Lingam and Abraham Loeb recently explored how interstellar spacecraft could harness the waves produced by a supernova explosion in the same way that sailing ships harness the wind.

The study that details their research, "Propulsion of Spacecrafts to Relativistic Speeds Using Natural Astrophysical Sources," recently appeared online and was also the subject of an article at Scientific American. As they explain in their study, it is possible that a sufficiently advanced civilization could use the blasts of energy released by supernovae to accelerate spacecraft to relativistic speeds.

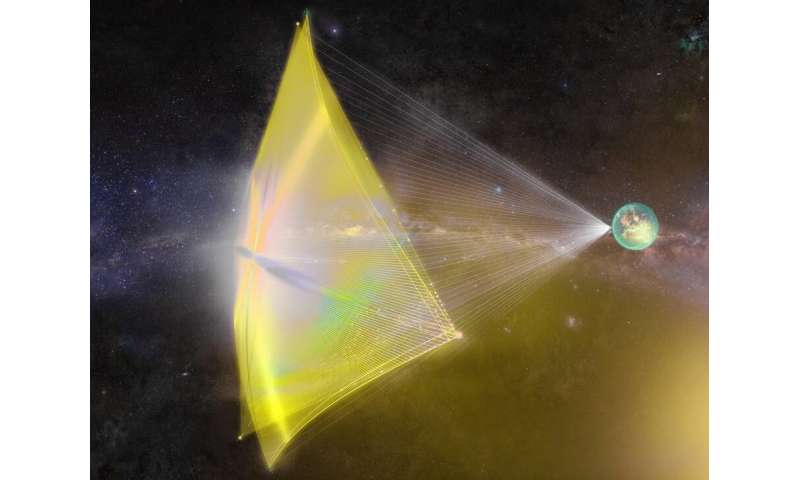

These spacecraft would be able to harness the explosive force using a light sail (AKA a solar sail) or a magnetic sail, two propulsion concepts that have been explored at length by astrophysicists. These concepts rely on the electromagnetic radiation generated by the sun to create pressure against a highly reflective sail, thus generating propulsion in a way that does not require engines or propellant.

Since propellant is one of the most significant contributors to a spacecraft's overall mass, light sail/magnetic sail concepts have the benefit of being much lighter than conventional spacecraft—and therefore, much cheaper to launch into space. Another possibility is to rely on directed energy (lasers) to accelerate this kind of spacecraft, allowing it to achieve speeds much higher than what would be possible with solar radiation alone.

Prof. Loeb, who in addition to being the Frank D. Baird Jr. Professor of Science at Harvard University, is also the chair of Breakthrough Starshot's Advisory Committee. As part of the nonprofit organization Breakthrough Initiatives, Starshot is currently working toward the creation of a light sail that would be accelerated by lasers to a speed of 20% the speed of light—allowing it to make the journey to Alpha Centauri in just 20 years.

As Loeb told Universe Today via email, it was while contemplating how such a spacecraft could be accelerated naturally that the idea of using supernova occurred to him:

"Back in December 2019, my wife and two daughters were on travel and I had the luxury of staying at home alone for a week and thinking about science. While taking a shower, I thought on how the sun is not effective at launching light sails to high speed, but a brighter source of light might be. I followed this thought with detailed calculations on supernovae, which are billions of times brighter than the sun for a week, and realized that lightsails with existing parameters can reach the speed of light if they are strategically placed ahead of time around the massive star that is about the explode."

Originally, Loeb explained this idea in an article that appeared in Scientific American on Feb. 6th, 2020, titled "Surfing a Supernova." The original article is also available on the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) website. As he argued there, a supernova would be capable of accelerating a light sail that weighs "less than half a gram per square meter to relativistic speeds," even if it were millions of kilometers away.

Simply put, the energy and brightness generated by a supernova are equivalent to what a billion suns would produce in an average month. Whereas solar wind would only be able to push a light sail up to one-thousandth the speed of light (0.01% or 0.001 c), a supernova could easily accelerate a sail to one-tenth the speed of light (0.1 c).

"My collaborator, Manasvi Lingam, saw my commentary and suggested that we write a full-fledged scientific paper on the subject exploring the feasibility of launching light sails to the speed of light around other bright sources, as well, such as black holes or pulsars," said Loeb. "I shared my notes with him and they seeded our collaborative paper."

To test this hypothesis, Lingam and Loeb considered how a light sail could be accelerated by the explosion of a number of astrophysical objects. This included massive stars, microquasars, supernovae, pulsarwind nebulae, and active galactic nuclei. As Lingam, who was the lead author on the resulting paper, explained to Universe Today via email:

"We developed mathematical models to determine the maximum speed that is attainable by light sails and electric sails. The maximum speeds varied depending on the propulsion system utilized, as well as the astrophysical objects in consideration."

For anyone who has the means, the advantages of this approach are obvious. Compared to conventional light sails and magnetic sails, a sail that takes advantage of the boost provided by an exploding star would be able to reach relativistic speeds without the need for expensive infrastructure (i.e., a large laser array).

Of course, the disadvantages of such a method are also obvious. For starters, there is the issue of timing. Not only are supernovae a rare occurrence; scientists are unable to accurately forecast them with anything other than a large margin of error—often millions of years. Anyone hoping to take advantage of exploding stars would need to be able to make more accurate estimates and be willing to wait a very long time.

But as Lingam and Loeb explored, the disadvantages go beyond this to include the particular hazards created by supernovae. As Loeb indicated:

"The main challenges are friction with the ambient gas, which may be dense in the vicinity of a massive star due to mass loss by winds. One can overcome the challenge by folding the sail throughout the journey except during the launch period when the opening of the sail can be triggered by the supernova flash of light."

On top of that, there are engineering and design challenges that would need to be addressed beforehand. First, the sails must be made of highly reflective material to avoid absorbing too much heat and burning up. Second, they would also need to be placed in a folded configuration until the star explodes to prevent them from being pushed away from their launch point by solar radiation.

Finally, the acceleration path of the sail must be carefully selected ahead of time to avoid any obstacles and minimize the risk of collision with large objects (like asteroids). Lastly, the sail itself must have some type of shielding or configuration to protect it from gas and solid particles in interstellar space. Given that the sail will be traveling at an incredibly high velocity, even the tiniest particles would pose an extreme collision risk.

As Lingam explained, their results show that these challenges are surmountable:

"There are many challenges such as sail stabilization, maintaining high reflectance and preventing heating, and avoiding damage while traveling in the source environment as well as the interstellar medium. Most of these issues may be overcome, at least in principle, by utilizing electric sails instead of light sails. Alternatively, if one decides to stick with light sails, then one will have to fold the sail during some stages of the voyage, choose an unusual sail architecture, and rely upon nanophotonic structures to improve stability."

In short, their results show that a sufficiently advanced species would be capable of positioning light sails/magnetic sails around dying stars so they could be accelerated once the star explodes. These sails could serve as messenger craft, demonstrating the existence of advanced civilizations by traveling to inhabited star systems.

In this respect, the feasibility of this interstellar concept could have implications in the ongoing Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI). As Loeb and colleagues have argued in previous studies, the possibility of directed-energy propulsion means that errant flashes of laser activity could be interpreted as a sign of technological activity (AKA technosignatures).

"This conceptual paradigm echoes the spirit of Dyson spheres, the megastructures hypothesized by Freeman Dyson for harvesting the energy of stars that aren't likely to explode," said Loeb. "If we are lucky to have many technological civilizations in our galaxy, there might be swarms of light sails around massive stars, patiently awaiting their explosions."

"In searching for technosignatures, our work suggests that one might look in the vicinity of high-energy astrophysical sources such as supernovae and quasars for radio signals, etc," added Lingam. "Of course, the probability of success is entirely dependent on whether such advanced technologies species exist—this is a question to which we do not have any answer yet."

For the time being, it looks like the Fermi Paradox is going to endure a little while longer. But with more things to be on the lookout for, and with next-generation telescopes coming online very soon, we are well-equipped to find evidence of extraterrestrial intelligence (if there is any to be found).What's the best way to sail from world to world? Electric sails or solar sails?

More information: Propulsion of Spacecrafts to Relativistic Speeds Using Natural Astrophysical Sources. arXiv:2002.03247v1 [astro-ph.IM]: arxiv.org/pdf/2002.03247.pdf

SHARING THIS OF COURSE MEANS I GET TO RECOMMEND ANOTHER GREAT SF BOOK BY SAMUEL R. DELANEY APTLY TITLED "NOVA" ABOUT SOLAR SAIL RACING AROUND A SUPERNOVA. WAY BACK IN 1968. FORWARD TO THE PAST

In 1967, Samuel R Delany, one of the first major black figures in the genre, and also a gay writer, had his novel Nova rejected for serialisation by John W Campbell, the hugely influential editor of Analog magazine, on the grounds that readers were not ready for black main characters.

The stated reason for the rejection should be placed in the context of Campbell’s enthusiastic support for the segregationist presidential candidate, and governor of Alabama, George Wallace.

The future of sci-fi never looked so bright As a gay female author, Becky Chambers is pushing back against the genre’s traditions Mon, Aug 26, 2019

Nova (novel) - Wikipedia

Nоva (1968) is a science fiction novel by American writer Samuel R. Delany. Nominally space opera, it explores the politics and culture of a future where cyborg technology is universal (the novel is one of the precursors to cyberpunk), yet making major decisions can involve using tarot cards.

January 8, 2020

Samuel R. Delany: Portrait of the Artist as a Young Super-Nova

Library of America has just republished Samuel R. Delany’s 1968 novel Nova in the two-volume anthology American Science Fiction: Eight Classic Novels of the 1960s, edited by Gary K. Wolfe. In the following guest column, cultural critic and Nation national affairs correspondent Jeet Heer explores the context from which Nova emerged and suggests some of the reasons for its classic status more than fifty years later.

By Jeet Heer

Samuel R. Delany: Portrait of the Artist as a Young Super-Nova

Library of America has just republished Samuel R. Delany’s 1968 novel Nova in the two-volume anthology American Science Fiction: Eight Classic Novels of the 1960s, edited by Gary K. Wolfe. In the following guest column, cultural critic and Nation national affairs correspondent Jeet Heer explores the context from which Nova emerged and suggests some of the reasons for its classic status more than fifty years later.

By Jeet Heer

First edition of Samuel R. Delany’s Nova (Doubleday, 1968).

Like math, like music, like gymnastics, science fiction is an endeavor that attracts the energy of the young. In the summer of 1967, shortly after he had finished writing Nova, Samuel R. Delany took an inventory of the youthful prodigies of the genre. “Isaac Asimov’s first story appeared when he was eighteen,” Delany noted. “John Brunner’s first novel when he was seventeen; Theodore Sturgeon’s first story when he was twenty. The list of SF [science fiction] writers who were in print before they could vote is impressive.”

The same is true of Delany himself. The voting age in 1962 was twenty-one. That year saw the release of Delany’s first published novel, The Jewels of Aptor, written when he was nineteen and released when he was twenty. It was followed at a clip of one or two books a year, resulting in eight more novels by 1968, culminating in the best book of his youth, Nova (1968). His early novels came out in such quick succession that many in the science fiction community assumed “Samuel Delany” was a house brand used by his publisher, Ace Books, to cover a multitude of authors. This idea was bolstered by Delany’s lack of any social connections to the world of science fiction fandom.

It was only after his appearance at the 24th World Science Fiction Convention, held in Cleveland in 1966, that Delany’s existence was recognized, which led to the quick consensus that he was a leading figure in the field. In 1967, the contentious editor Harlan Ellison wrote that Delany gave “an indefinable but commanding impression that this was a young man with great work in him.” The following year, Algis Budrys, a respected novelist and at the time the sharpest critic in science fiction, hailed Nova by saying the novel proved that “right now, as of this book” Delany is “the best science-fiction writer in the world, at a time when competition for that status is intense.” Delany was all of twenty-six years old when he earned that accolade.

If Delany was celebrated by some as a wunderkind possessing (in Budrys’ words) “star quality” not everyone appreciated the future he was offering. Delany’s biography made him an anomaly in the world of science fiction, at the time an overwhelmingly white genre with a streak of political conservatism. Delany was a gay, African-American man who, at the time, lived off-and-on in an open marriage with the white poet Marilyn Hacker (who would later identify herself as a lesbian). A queer sensibility ran through much of his fiction, notably the Hugo–winning short story “Aye, and Gomorrah. . .” (1967).

Equally evident in Delany’s fiction was a desire to depict a culturally and racially heterogeneous future, a goal that distinguished his fiction in a genre where the norms of the white American middle class was often presented as a kind of default mode even when representing putatively alien cultures. To be sure, some writers made a diligent effort to present a multiracial future, notably Robert Heinlein, whose Starship Troopers (1959) impressed the teenage Delany for the casual way it handled the fact the main character was a person of color and of Filipino descent. But Heinlein’s characters, whether white or people of color, all talk the same: there is no felt sense of class or cultural diversity in his work. Delany, by contrast, never depicts a monoculture: his characters are always situated by language, history, and class.

Lorq Von Ray, the crazed space captain who serves as the anti-hero of Nova, is of Norwegian and Senegalese descent. The crew that von Ray commands is also racially mixed, with characters who, in inadequate shorthand form, can be described as African, Asian, or Romani (the Mouse, referred in the book by the then commonly used term as a Gypsy).

Before Nova was published, Delany’s agent Henry Morrison offered it for possible serialized excerpt to John W. Campbell, the editor of the best-selling American science fiction journal Analog. Although Campbell was a cranky and polarizing figure in the field, his editorship was influential and he played a key role in midwifing many classic works, notably Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series, Robert Heinlein’s Future History stories, and Frank Herbert’s Dune.

Campbell told Morrison he liked Nova but didn’t think his readers would accept a black protagonist.

It’s easy to write off Campbell as an embarrassing reactionary. Analog by 1968 was well past its prime and had devolved into a magazine publishing stories of heroic engineers always besting their foes, ranging from space aliens to government bureaucrats. The fiction wasn’t enhanced by Campbell’s habit of writing contrarian editorials celebrating smoking, slavery, and the segregationist Alabama governor George Wallace.

But Delany also fared nearly as badly with an editor who was Campbell’s polar opposite, Michael Moorcock, the impresario behind England’s New Worlds magazine. In the pages of his journal, Moorcock was a leading proponent of “New Wave” science fiction, a movement to modernize the genre by bringing in the techniques of experimental fiction and a focus on pressing social and political debates.

Delany published a story in New Worlds and the capacious label of New Wave science fiction was often fixed on him. Certainly, he shared one aspect of the New Wave agenda. He had grown up reading both science fiction and modernist writers like James Joyce, T. S. Eliot, and Arthur Rimbaud. Like such indisputable New Wave masters as J. G. Ballard and Brian Aldiss, Delany eschewed slapdash pulp writing and aimed to write science fiction with the same linguistic inventiveness of the high modernists.

Yet despite this important commonality, Delany was never at ease with the New Wave movement. “Basically, during the sixties, Moorcock and the writers associated with the New Wave did not particularly enjoy my work,” Delany told anthologists Kathryn Cramer and David Hartwell in 2006. “Though we all got along well socially, Moorcock told me that the only book of mine he liked enough to publish himself was Empire Star—no doubt because the political allegory of North American slavery and the LII was so clear. But when Nova was reviewed in New Worlds by M. John Harrison, the basic thrust was: What a shame someone so talented is wasting his time with this far future space opera nonsense.”

Like math, like music, like gymnastics, science fiction is an endeavor that attracts the energy of the young. In the summer of 1967, shortly after he had finished writing Nova, Samuel R. Delany took an inventory of the youthful prodigies of the genre. “Isaac Asimov’s first story appeared when he was eighteen,” Delany noted. “John Brunner’s first novel when he was seventeen; Theodore Sturgeon’s first story when he was twenty. The list of SF [science fiction] writers who were in print before they could vote is impressive.”

The same is true of Delany himself. The voting age in 1962 was twenty-one. That year saw the release of Delany’s first published novel, The Jewels of Aptor, written when he was nineteen and released when he was twenty. It was followed at a clip of one or two books a year, resulting in eight more novels by 1968, culminating in the best book of his youth, Nova (1968). His early novels came out in such quick succession that many in the science fiction community assumed “Samuel Delany” was a house brand used by his publisher, Ace Books, to cover a multitude of authors. This idea was bolstered by Delany’s lack of any social connections to the world of science fiction fandom.

It was only after his appearance at the 24th World Science Fiction Convention, held in Cleveland in 1966, that Delany’s existence was recognized, which led to the quick consensus that he was a leading figure in the field. In 1967, the contentious editor Harlan Ellison wrote that Delany gave “an indefinable but commanding impression that this was a young man with great work in him.” The following year, Algis Budrys, a respected novelist and at the time the sharpest critic in science fiction, hailed Nova by saying the novel proved that “right now, as of this book” Delany is “the best science-fiction writer in the world, at a time when competition for that status is intense.” Delany was all of twenty-six years old when he earned that accolade.

If Delany was celebrated by some as a wunderkind possessing (in Budrys’ words) “star quality” not everyone appreciated the future he was offering. Delany’s biography made him an anomaly in the world of science fiction, at the time an overwhelmingly white genre with a streak of political conservatism. Delany was a gay, African-American man who, at the time, lived off-and-on in an open marriage with the white poet Marilyn Hacker (who would later identify herself as a lesbian). A queer sensibility ran through much of his fiction, notably the Hugo–winning short story “Aye, and Gomorrah. . .” (1967).

Equally evident in Delany’s fiction was a desire to depict a culturally and racially heterogeneous future, a goal that distinguished his fiction in a genre where the norms of the white American middle class was often presented as a kind of default mode even when representing putatively alien cultures. To be sure, some writers made a diligent effort to present a multiracial future, notably Robert Heinlein, whose Starship Troopers (1959) impressed the teenage Delany for the casual way it handled the fact the main character was a person of color and of Filipino descent. But Heinlein’s characters, whether white or people of color, all talk the same: there is no felt sense of class or cultural diversity in his work. Delany, by contrast, never depicts a monoculture: his characters are always situated by language, history, and class.

Lorq Von Ray, the crazed space captain who serves as the anti-hero of Nova, is of Norwegian and Senegalese descent. The crew that von Ray commands is also racially mixed, with characters who, in inadequate shorthand form, can be described as African, Asian, or Romani (the Mouse, referred in the book by the then commonly used term as a Gypsy).

Before Nova was published, Delany’s agent Henry Morrison offered it for possible serialized excerpt to John W. Campbell, the editor of the best-selling American science fiction journal Analog. Although Campbell was a cranky and polarizing figure in the field, his editorship was influential and he played a key role in midwifing many classic works, notably Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series, Robert Heinlein’s Future History stories, and Frank Herbert’s Dune.

Campbell told Morrison he liked Nova but didn’t think his readers would accept a black protagonist.

It’s easy to write off Campbell as an embarrassing reactionary. Analog by 1968 was well past its prime and had devolved into a magazine publishing stories of heroic engineers always besting their foes, ranging from space aliens to government bureaucrats. The fiction wasn’t enhanced by Campbell’s habit of writing contrarian editorials celebrating smoking, slavery, and the segregationist Alabama governor George Wallace.

But Delany also fared nearly as badly with an editor who was Campbell’s polar opposite, Michael Moorcock, the impresario behind England’s New Worlds magazine. In the pages of his journal, Moorcock was a leading proponent of “New Wave” science fiction, a movement to modernize the genre by bringing in the techniques of experimental fiction and a focus on pressing social and political debates.

Delany published a story in New Worlds and the capacious label of New Wave science fiction was often fixed on him. Certainly, he shared one aspect of the New Wave agenda. He had grown up reading both science fiction and modernist writers like James Joyce, T. S. Eliot, and Arthur Rimbaud. Like such indisputable New Wave masters as J. G. Ballard and Brian Aldiss, Delany eschewed slapdash pulp writing and aimed to write science fiction with the same linguistic inventiveness of the high modernists.

Yet despite this important commonality, Delany was never at ease with the New Wave movement. “Basically, during the sixties, Moorcock and the writers associated with the New Wave did not particularly enjoy my work,” Delany told anthologists Kathryn Cramer and David Hartwell in 2006. “Though we all got along well socially, Moorcock told me that the only book of mine he liked enough to publish himself was Empire Star—no doubt because the political allegory of North American slavery and the LII was so clear. But when Nova was reviewed in New Worlds by M. John Harrison, the basic thrust was: What a shame someone so talented is wasting his time with this far future space opera nonsense.”

Samuel R. Delany in 1997. (Jack Mitchell/Getty Images)

The preferred mode of New Wave science fiction was near-future extrapolation. In Nova and Babel–17 (1966), Delany unabashedly embraced space opera, at the time a déclassé sub-genre within science fiction. Nova is set in the far future (the thirty-second century) in a universe of marvels like faster-than-light space travel, countless colonized planets, and widespread merging of humans and machines into cyborgs. (The way Delany’s characters jack into technology planted the seeds for a subgenre that would flourish in the 1980s: cyberpunk).

The narrative involves nothing less than a battle between feuding aristocratic clans for the fate of the universe. This was operatic in more ways than one: Lorq Von Ray is not a character with an internal life but a larger-than-life myth figure, part Ahab and part Prometheus.

This type of exuberant space opera was very much not in fashion in science fiction in the 1960s. Science fiction was a ghetto literature, but there was a hierarchy even in that ghetto. Readers of Campbell’s Analog prized “hard science fiction” that celebrated rationality and allegedly played by the rules of known physics. Moorcock’s New Worlds upheld the value of science fiction that savagely satirized the contemporary media-saturated world. Both Analog and New Worlds looked down on slam-bang planet-hopping space opera.

Delany has a recurring habit of picking up genres that are snobbishly dismissed by other writers and trying to write them with literary care. He’s done that not just with space opera but also sword and sorcery (in the Nevèrÿon novels), superhero comics (his abortive 1972 run on Wonder Woman) and pornography (in novels like Hogg and Mad Man). It seems to be one of Delany’s credos that no genre is beneath contempt, that a good writer can work with any material.

READ NOVA IN:

American Science Fiction:

Eight Classic Novels of the 1960s

Delany’s recuperation of space opera was as influential as his role as a precursor to cyberpunk. Nova and another Delany novel, Babel-17 (1966), were important forerunners to the “space opera renaissance” that picked up speed in the late 1970s and continues to define the field to the present. Without Delany, it’s hard to imagine the work of Lois McMaster Bujold, Iain M. Banks, Dan Simmons, and countless others.

Nova is in part a meditation on novel writing. It’s set in a socially static world where the novel as an art form has become obsolete. Part of the promised rebirth depicted in the book is of the social conditions that make novel writing possible.

As writer D. J. Johnson points out, the word “nova” has the same etymological roots as the word “novel” (both grounded in the Latin word for new, novum). The two sides of Delany’s own artistic personality are shown in the contrasting characters of Katin Crawford, a cerebral would-be novelist, and Pontichos Provechi (a.k.a. the Mouse), a street urchin who makes money playing the “sensory syrynx” (a device that lets him conjure up sounds, smells, and 3-D images).

Like Crawford, Delany is a very deliberate writer who filled up countless pages of his journal planning out his ideas. But Delany in the early 1960s was also a street musician like the Mouse. Delany’s folk singing in the coffee houses of New York and Europe often earned him more money in the early 1960s than novel writing, and was a crucial source of income.

Part of the argument of Nova is that a novelist has to be both an intellectual like Crawford and an instinctive artist like the Mouse: the artist has to be both theoretically ambitious and alive to sensory experience.

In Nova, we see that Delany’s revitalization of space opera took place on a sentence by sentence level. Delany’s synesthetic prose achieves the same effect as the Mouse’s “sensory syrinx.” Here’s a description from the first chapter of the night sky on Triton:

The shrunken sun lay jagged gold on the mountains. Neptune, huge in the sky, dropped mottled light on the plain. The starships hulked in the repair pits half a mile away.

Delany, here and in all his best works, gives us a future we can immerse ourselves in, a future as dense, diverse, and strange as reality itself.

Jeet Heer is a national affairs correspondent at The Nation and the author of In Love with Art: Francoise Mouly’s Adventures in Comics with Art Spiegelman (2013) and Sweet Lechery: Reviews, Essays and Profiles (2014). The latter book contains essays on science fiction writers Robert Heinlein, Philip K. Dick, and Stanislaw Lem.

The preferred mode of New Wave science fiction was near-future extrapolation. In Nova and Babel–17 (1966), Delany unabashedly embraced space opera, at the time a déclassé sub-genre within science fiction. Nova is set in the far future (the thirty-second century) in a universe of marvels like faster-than-light space travel, countless colonized planets, and widespread merging of humans and machines into cyborgs. (The way Delany’s characters jack into technology planted the seeds for a subgenre that would flourish in the 1980s: cyberpunk).

The narrative involves nothing less than a battle between feuding aristocratic clans for the fate of the universe. This was operatic in more ways than one: Lorq Von Ray is not a character with an internal life but a larger-than-life myth figure, part Ahab and part Prometheus.

This type of exuberant space opera was very much not in fashion in science fiction in the 1960s. Science fiction was a ghetto literature, but there was a hierarchy even in that ghetto. Readers of Campbell’s Analog prized “hard science fiction” that celebrated rationality and allegedly played by the rules of known physics. Moorcock’s New Worlds upheld the value of science fiction that savagely satirized the contemporary media-saturated world. Both Analog and New Worlds looked down on slam-bang planet-hopping space opera.

Delany has a recurring habit of picking up genres that are snobbishly dismissed by other writers and trying to write them with literary care. He’s done that not just with space opera but also sword and sorcery (in the Nevèrÿon novels), superhero comics (his abortive 1972 run on Wonder Woman) and pornography (in novels like Hogg and Mad Man). It seems to be one of Delany’s credos that no genre is beneath contempt, that a good writer can work with any material.

READ NOVA IN:

American Science Fiction:

Eight Classic Novels of the 1960s

Delany’s recuperation of space opera was as influential as his role as a precursor to cyberpunk. Nova and another Delany novel, Babel-17 (1966), were important forerunners to the “space opera renaissance” that picked up speed in the late 1970s and continues to define the field to the present. Without Delany, it’s hard to imagine the work of Lois McMaster Bujold, Iain M. Banks, Dan Simmons, and countless others.

Nova is in part a meditation on novel writing. It’s set in a socially static world where the novel as an art form has become obsolete. Part of the promised rebirth depicted in the book is of the social conditions that make novel writing possible.

As writer D. J. Johnson points out, the word “nova” has the same etymological roots as the word “novel” (both grounded in the Latin word for new, novum). The two sides of Delany’s own artistic personality are shown in the contrasting characters of Katin Crawford, a cerebral would-be novelist, and Pontichos Provechi (a.k.a. the Mouse), a street urchin who makes money playing the “sensory syrynx” (a device that lets him conjure up sounds, smells, and 3-D images).

Like Crawford, Delany is a very deliberate writer who filled up countless pages of his journal planning out his ideas. But Delany in the early 1960s was also a street musician like the Mouse. Delany’s folk singing in the coffee houses of New York and Europe often earned him more money in the early 1960s than novel writing, and was a crucial source of income.

Part of the argument of Nova is that a novelist has to be both an intellectual like Crawford and an instinctive artist like the Mouse: the artist has to be both theoretically ambitious and alive to sensory experience.

In Nova, we see that Delany’s revitalization of space opera took place on a sentence by sentence level. Delany’s synesthetic prose achieves the same effect as the Mouse’s “sensory syrinx.” Here’s a description from the first chapter of the night sky on Triton:

The shrunken sun lay jagged gold on the mountains. Neptune, huge in the sky, dropped mottled light on the plain. The starships hulked in the repair pits half a mile away.

Delany, here and in all his best works, gives us a future we can immerse ourselves in, a future as dense, diverse, and strange as reality itself.

Jeet Heer is a national affairs correspondent at The Nation and the author of In Love with Art: Francoise Mouly’s Adventures in Comics with Art Spiegelman (2013) and Sweet Lechery: Reviews, Essays and Profiles (2014). The latter book contains essays on science fiction writers Robert Heinlein, Philip K. Dick, and Stanislaw Lem.

Destruction and Renewal: Nova by Samuel R. Delany

Alan Brown

In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

There are authors who work with the stuff of legends and make it new and fresh and all their own. There are authors who make their prose sing like it was poetry, and authors whose work explores the cosmos in spaceships, dealing with physics and astronomy. And in a few rare cases, there are authors who bring all those elements together into something magical. One of those authors is Samuel R. Delany, whose book Nova is a classic of the genre.

Delany, still in his 20s, burst onto the science fiction scene of the 1960s like a nova himself. He has been nominated for many awards, and won two Nebulas back to back in 1966 and 1967. My first exposure to his work was The Einstein Intersection, a reworking of the legend of Orpheus. My second was Nova, which became a lifelong favorite. In Nova, he created a novel that works on many levels, including myth and legend, unfolding against a solidly-researched science fiction background. There are other authors who would happily build an entire book around merely a tenth of the ideas that Delany packs into Nova. After Nova, I’ve continued to read the author’s work, and while I appreciated the craftsmanship in novels like Dhalgren and Triton, nothing ever hit my personal sweet spot like the headlong narrative rush of Nova.

What I did not know at the time, as I was not yet connected to SF fandom, and because it was not mentioned on the paperback copies of his books, was that Delany is African-American and a gay man. So he was not only winning awards (at a remarkably young age), he was breaking down barriers in the SF community, which at the time was overwhelmingly dominated by white male authors.

About the Author

Samuel R. Delany (born 1942) is a native of New York, who grew up in Harlem and attended the Bronx High School of Science and City College. In his younger days, he traveled the world, working in a variety of jobs before he reached the point where he could support himself with his writing. Delany became a professor in 1988 and has taught at several universities, most notably serving on the faculty of Temple University’s English Department from 2001 until he retired in 2015. He received vital support early in his career from editor Fred Pohl, and was quickly and widely acclaimed from the start of his career as a gifted and skillful author. He has won the Hugo Award twice and the Nebula award four times, collecting many more nominations for those awards over the years. In addition to Nova, his novels include Babel-17 (Nebula Award winner in 1966), The Einstein Intersection (Nebula Award winner in 1967), The Fall of the Towers, The Jewels of Aptor, and Dhalgren. Of his many short stories, “Aye, and Gomorrah…” won the Nebula Award in 1967, and “Time Considered as a Helix of Semi-Precious Stones” won both the Hugo and Nebula Awards in 1968. He won another Hugo, in the Best Related Work category, in 1989 for The Motion of Light in Water: Sex and Science Fiction Writing in the East Village 1957-1965. He was inducted into the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame in 2002, and named as a Science Fiction Writers of America Grand Master in 2013.

Mr. Delany has been called “the first African-American science fiction writer,” a label he rejected in a New York Review of Science Fiction article in August 1998, pointing out several African-American authors before him who wrote stories that could be identified as science fiction. If not the first to write in the genre, however, he was definitely the first to make such a large and lasting impact on the genre right from the beginning of his writing career. During his career, he also came out as gay, and did not shy away from including sexual situations in his fiction. This reportedly caused some discomfort among booksellers and publishers at the time. When Mr. Delany started his career, science fiction writers and the characters they portrayed were largely male, white, and heterosexual (particularly when it came to their protagonists). Mr. Delany has been a pioneer in changing that, and helped to open the doors of the science fiction genre for the many diverse authors who followed in his footsteps.

The World of Nova

In the novel, which takes place in the 32nd Century CE, human civilization is split between the Earth-led worlds of Draco and the worlds of the Pleiades star cluster, where shorter travel distances have allowed a younger confederation to blossom. These powers compete in the non-aligned Outer Colonies. The economy of these worlds is controlled by a few families, whose power exceeds that of the robber barons of the United States at the end of the 19th Century. The Pleiades worlds are dominated by the Von Ray family, while the Draco worlds are dominated by the Reds of Red Shift Ltd. The Von Ray family has played a large role in keeping the Pleiades free from domination by the corporations of Draco—something that is seen as patriotism among the Pleiades, but as piracy by the people of Draco.

This future civilization is fueled by the fictional element Illyrion, a power source like none ever seen before. There is not much of this element available, but even the smallest amounts can generate huge amounts of energy. The discovery of even modest amounts of Illyrion could completely upset the balance of power among human worlds. From a scientific standpoint, while Transuranium elements tend toward faster and faster radioactive decay rates as they get heavier, scientists have long speculated that there might be “islands of stability,” where super-heavy elements such as the fictional Illyrion exist. No trace of these elements has ever been found in nature, but they remain an intriguing possibility.

Novas have long captured the imagination of those who watch the sky. The very idea of a star becoming unstable and exploding into cosmic fury—one that could destroy every world that orbits—it is both frightening and fascinating. Scientists now separate the phenomena into two types of events: classical novas, which are caused by two binary stars interacting, and supernovas, which involve a massive star exploding toward the end of its lifespan. Supernovas can reshape the elements of the star itself in a process known as nucleosynthesis.

Interstellar travel in Delany’s 32nd Century, which involves journeys at speeds faster than light, is made possible by manipulating the flow of forces unknown to us today in a process akin to sailing. These forces of the space-time continuum are accessed by energy vanes, each of which is controlled by a computer operated by the “cyborg studs” who make up the crew of a starship.

Most humans have been outfitted with cybernetic control sockets in their wrists and at base of their spines. This allows them to control a range of devices and power tools, from vacuum cleaners to mining machines and right up to starships. It also allows people to be much more flexible in moving from career to career. Some reviewers have drawn a parallel between these sockets and the jacks that would later appear as a popular element in the cyberpunk genre. But unlike those jacks, which connect people with a virtual world that stands apart from the physical world, the sockets in this novel connect people to devices in the physical world, and allow the physical world to be sensed in different ways.

Nova

As the novel opens, we meet a young man from Earth nicknamed The Mouse, a cyborg stud who has been knocking around the Solar System, looking for a berth aboard an interstellar ship; he’s also a musician who plays the multi-media sensory-syrynx. On a terraformed moon of Neptune, the Mouse meets a ruined and blind old man, Dan, who rants about diving into a star for Captain Lorq Von Ray. He then meets Katin, a young intellectual from Luna, and the two of them encounter Von Ray, who is not only looking for Dan, but is also looking to form a new crew. Von Ray has a hideously scarred face, and is more than a bit obsessive. The Mouse and Katin agree to join his crew, along with the brothers Lynceos and Idas, and the couple Sebastian and Tyÿ, who have amorphous, black, flying pet “gillies” accompanying them. Von Ray tells them they are heading toward a nova, attempting something that has led to failure twice before, and in a race with scions of one of Draco’s most powerful families, Prince Red and his sister Ruby Red. Poor Dan stumbles into a volcanic chasm and dies—he’s not the last character in the book that will meet a fiery fate.

The story not only charts the preparations of this crew and their voyage to their nova, but reveals Von Ray’s motivation through two long flashback scenes. The first is a childhood encounter between Lorq, Prince Red, and Ruby Red on Lorq’s homeworld. Prince Red has a birth defect that has damaged one of his arms, and wears a cybernetic prosthesis. He has been sheltered and coddled by his family to the point where he sees even a mention of his arm as a personal insult, and shows signs of a cruel and sadistic nature. Lorq is attracted to Ruby Red, who is already dominated by her brother’s forceful personality.

The second flashback involves another encounter between Lorq, Prince, and Ruby. Lorq has become an accomplished spaceship racer, and is invited by the Reds to a costume party on Earth. When he arrives, Prince gives him a pirate costume. Lorq has not paid much attention to his family history, and it falls to Ruby to explain that the pirate costume is an insult. He is again attracted to Ruby, who remains unhealthily devoted to her cruel brother. There is a confrontation, and Prince attacks Lorq, leaving him with a scarred face. Lorq returns to his family, finds out from his father that Draco is finally making inroads into the Pleiades, and that unless something changes, they will lose their independence, and his family will lose its fortune. Lorq decides to keep his facial scar as a reminder of his duty, and develops a plan to harvest Illyrion from an exploding star, upsetting the interstellar economy in the favor of the Pleiades. His first attempt, with a carefully selected crew, leaves Dan crippled, and Lorq decides to depend more on chance than planning in his second attempt.

Lorq is reckless and driven, and constantly seeks personal confrontations with Prince Red, even when they are unwise. His search for a crew in the heart of Draco is just one sign of his aggressive approach. His randomly selected crew does prove useful, as at one point Sebastian’s pets save him from Prince, and he draws inspiration and guidance from the various crew members, especially Tyÿ, who is a skilled reader of Tarot cards.

I will refrain from further summary of the plot, because if you haven’t read this book, you should do so at your earliest convenience, and I don’t want to spoil things. Suffice it to say, the nova of the title is not only a physical presence: it also represents conflict and destruction, along with renewal and rebirth.

Katin and the Mouse represent two different vehicles for the author’s viewpoint to enter the story. Delany worked as a guitarist and singer in his younger days, and Mouse represents the attitude of a performing musician, focused on senses, emotions, and the immediacy of the moment. Katin, on the other hand, is an intellectual and a Harvard graduate, and his continual note-taking for a novel he has yet to start offers a wry commentary on an author’s challenges. Katin is cleverly used as a vehicle for expository information, as he has a habit of lecturing people. The observations of Katin and the Mouse on the events of the novel are entertaining and often amusing.

Delany draws on his travels around the world, and the book is notable for the diversity of its characters and the various cultures it portrays, especially among Lorq’s crew. Lorq is the son of a mother with Senegalese heritage, while his father’s heritage is Norwegian. Mouse is of Romani heritage, Dan is Australian, Katin is from Luna, Sebastian and Tyÿ are from the Pleiades, and the twin brothers Lynceos and Idas are of African descent, with one being an albino.

Delaney explicitly evokes Tarot cards and grail quest legends in the book, but I also noted an array of other possible influences, as well. Dan reminded me of the old blind sailor Pew who sets the plot in motion in Stevenson’s Treasure Island. Von Ray’s obsession recalls Captain Ahab’s search for the white whale in Melville’s Moby-Dick. There is also a hint of Raphael Sabatini’s protagonists in Von Ray, a man driven by a need for revenge. And perhaps most strongly of all, Von Ray functions as an analog for Prometheus, striving and suffering to bring fire to his people. The book works on many levels, and is all the stronger for it.

Final Thoughts

Nova worked well upon my first readings, and holds up surprisingly well after fifty years. There are very few of the obvious anachronisms you often find in older works, where new developments in real life society and science have rendered the portrayed future as obsolete. The book contains interesting scientific speculation, social commentary, compelling characters, and action and adventure aplenty. I would recommend it without reservation to anyone who wants to read an outstanding science fiction novel.

And now, as I always do, I yield the floor to you. Have you read Nova, and if so, what did you think? What are your thoughts on other works by Delany? And how do you view his work in terms of the history of the science fiction field?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.

Overloading the senses: Samuel Delany’s Nova

Jo Walton

I can’t think of any other book that’s anything like as old as Nova (1968!) that feels as modern. There’s nothing here to apologize for or to smile ruefully over—there’s one mention that by the end of the twentieth century humanity was on more than one planet, and that’s it. This book was written the year before the moon landing, and it could have been written tomorrow without changing a word.

Not only is it not dated, but it feels exciting, it feels cutting edge, it feels like something I want to get my friends to read and talk about and get their heads blown off by. I’m so enthusiastic about how terrific this is that I want to jump up and down, saying “Nova! Read Nova! Do you know how good it is?” Of course, since it came out in 1968 everybody has read it already—or have you? If it’s sitting there looking like something you ought to get around to one day—pick it up! You’ll be so glad you did.

I reviewed it here before. But I was itching to read it again, and I’ve thought of some new things to say about it.

Thematic spoilers but no plot spoilers.

The theme of Nova is sensory stimulus. There’s Dan, who had his senses burned out observing a nova, so now he sees and hears and smells and touches everything through the brightness of that overload. There’s Mouse, who has a sensory syrynx, an instrument that makes music, scents, images. The songs of the syrnyx run through that story, and it can also be used as a weapon. There’s the universe itself, complex, brightly layered, divided into three political groupings, with fashions and art forms and museums and jobs (everything from manufacturing to controlling spaceships) that are done by people jacked in to computers. There are lost aliens and new elements and levels of sophistication and revenge and superstition and desire. Delany succeeds in making this a fully realised and kaleodoscopic future. He tells us some things and shows us some things and implies other things and it all overlaps and keeps moving. It seems fractally complex like real human societies and yet it’s comprehensible.

Nova is a book with layers of mythological reference—grail quest especially, but also other quests, Golden Fleece, the Flying Dutchman. I think I’ve figured out what it’s doing with them, which is what confused the heck out of me originally and put me off the book. You know how sometimes people write something that’s supposed to be the origin of a legend—the true story that inspired the myths? This is that only backwards, it’s what the myths prefigure, so none of it maps directly, the myths are foreshadowings. Or, better, you know how figures from different myth cycles all come together on the Argo, or at Camelot? This accretion has happened here, and the legend of Lorq von Ray has attached to itself all these other trailing bits of quests. What that does it gives it resonance, echoes, facets, rather than establishing parallels the way these things normally do.

Delany’s writing is often poetic and never more than here, where every metaphor is in service to the whole. This is the first page, Dan tells Mouse his story, as he tells everyone, ancient mariner that he is:

“We were moving out, boy, with the three hundred suns of the Pleiades glittering like a puddle of jewelled milk on our left, and all blackness wrapped around our right. The ship was me; I was the skip. With these sockets—” he tapped the insets on his wrists against the table, click “—I was plugged into my vane-projector. Then —” the stubble on his jaw rose and fell with the words “—centered on the dark, a light! It reached out, grabbed our eyes as we lay in the projection chambers and wouldn’t let them go. It was like the universe was torn and all day raging through. I wouldn’t go off sensory input. I wouldn’t look away. All the colours you could think of were there, blotting the night. And finally the shock waves; the walls sang. Magnetic inductance oscillated over our ship, nearly rattled us apart. But then it was too late. I was blind.”

I mentioned last time that the book has surprisingly interesting economics. This is a universe with rich people and poor people and people in the middle. You don’t usually expect to see a grail-type quest set up with rational economics that make sense, but here we have that. There’s a theory of labour, too, along with theories about art and revenge and love. There are also changing fashions in music and clothes, which is notable. There’s a style of music just coming in, edgy, and ten years later it’s nostalgia. This is what really happens, but it’s rare to see it in science fiction, where you so often have things that define a planet and continue to define it.

We start seeing Lorq Von Ray as the Flying Dutchman, and then we go back along his life and how he has grown to the point where we first see him. It’s a portait of a man and a society. Something I noticed this time is that our point of view characters are this one rich man, Katin, who is educated middle class, and Mouse, who is a gypsy, who grew up without insets, poor around the Mediterranean. He’s from Earth, Katin is from the moon, and Lorq is from the Pleiades. The three of them triangulate on the story, on the universe, and on the way it is told. What Mouse sees, what Katin sees, and what Lorq sees are different facets, which is part of what gives us such a faceted universe.

They’re all men and so is the villain, Prince—the book is short of women. Those there are are iconic—Ruby Red, and Tyy, and Celia. Ruby is Prince’s sister, who is a love interest for Lorq and her brother’s helper. She’s a character and she has agency but she’s more icon than person. Tyy reads the cards, she’s one of the crew, but she’s very minor except as soothsayer. Celia is more a piece of background than a person. She’s a terrific piece of background—but that’s all she is. She’s Lorq’s aunt, she’s the curator of a museum. Her politician husband was assassinated years before. And it’s a great example of our angles on the world. To Lorq it was the heartbreaking death of a family member. To Katin it’s a huge political event, he has seen it through the media, one of those epoch changing things. Mouse has vaguely heard of it, he wasn’t paying attention, he can’t remember if Morgan killed Underwood or if Underwood killed Morgan.

This is a short book, but there’s a lot in it, and I can see myself coming back to it over and over and finding more in it every time. Maybe in a few years time I’ll write you a calm coherent post about Nova. For now: wow.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She has a ninth novel coming out in January, Among Others, and if you liked this post you will like it. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.