The Confounding Truth About Frederick Douglass

Throughout his life, however, Douglass repeatedly fell victim to the brutalizations and insults commonly experienced by African Americans of his time. As a slave, he suffered at the hands of a vicious “nigger breaker” to whom he was rented. He fled to the “free” North, only to have his work as a maritime caulker thwarted by racist white competitors. As a traveling evangelist for abolitionism, he was repeatedly ejected from whites-only railroad cars, restaurants, and lodgings. When he died, an admiring obituary in The New York Times suggested that Douglass’s “white blood” accounted for his “superior intelligence.” After his death, his reputation declined precipitously alongside the general standing of African Americans in the age of Jim Crow.

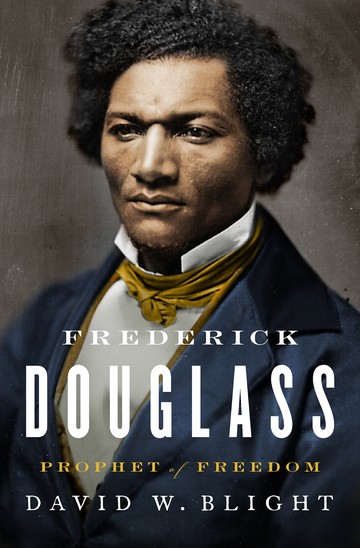

Now everyone wants a piece of Frederick Douglass. When a statue memorializing him was unveiled at the United States Capitol in 2013, members of the party of Paul Ryan and Mitch McConnell sported buttons that read frederick douglass was a republican. More recently, the Republican National Committee issued a statement joining President Donald Trump “in honoring Douglass’ lifelong dedication to the principles that define [the Republican] Party and enrich our nation.” Across the ideological divide, former President Barack Obama has lauded Douglass, as has the leftist intellectual Cornel West. New books about Douglass have appeared with regularity of late, and are now joined by David W. Blight’s magnificently expansive and detailed Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom.![]() SIMON & SCHUSTER

SIMON & SCHUSTER

A history professor at Yale who has long been a major contributor to scholarship on Douglass, slavery, and the Civil War, Blight portrays Douglass unequivocally as a hero while also revealing his weaknesses. Blight illuminates important facets of 19th-century political, social, and cultural life in America, including the often overlooked burdens borne by black women. At the same time, he speaks to urgent, contemporary concerns such as Black Lives Matter. Given the salience of charges of cultural misappropriation, griping about his achievement would be unsurprising: Blight is a white man who has written the leading biography of the most outstanding African American of the 19th century. His sensitive, careful, learned, creative, soulful exploration of Douglass’s grand life, however, transcends his own identity.

In the wake of Douglass’s death in 1895, it was African Americans who kept his memory alive. Booker T. Washington wrote a biography in 1906. The historian Benjamin Quarles wrote an excellent study in 1948. White historians on the left also played a key role in protecting Douglass from oblivion, none more usefully than Philip Foner, a blacklisted Marxist scholar (and uncle of the great historian Eric Foner), whose carefully edited collection of Douglass’s writings remains essential reading. But in “mainstream”—white, socially and politically conventional—circles, Douglass was widely overlooked. In 1962, the esteemed literary critic Edmund Wilson published Patriotic Gore: Studies in the Literature of the American Civil War, a sprawling (and lavishly praised) commentary on writings famous and obscure that omitted Douglass, and virtually all the other black literary figures of the period.

Keenly attuned to the politics of public memory, Blight shows that the current profusion of claims on Douglass’s legacy bears close scrutiny: Claimants have a way of overlooking features of his complex persona that would be embarrassing for them to acknowledge. Conservatives praise his individualism, which sometimes verged on social Darwinism. They also herald Douglass’s stress on black communal self-help, his antagonism toward labor unions, and his strident defense of men’s right to bear arms. They tiptoe past his revolutionary rage against the United States during his early years as an abolitionist. “I have no patriotism,” he thundered in 1847. “I cannot have any love for this country … or for its Constitution. I desire to see it overthrown as speedily as possible.” Radical as to ends, he was also radical as to means. He justified the violence deployed when a group of abolitionists tried to liberate a fugitive slave from a Boston jail and killed a deputy U.S. marshal in the process. Similarly, he assisted and praised John Brown, the insurrectionist executed for murder and treason in Virginia in 1859.

Many conservatives who claim posthumous alliance with Douglass would abandon him if they faced the prospect of being publicly associated with the central features of his ideology. After all, he championed the creation of a strong post–Civil War federal government that would extend civil and political rights to the formerly enslaved; protect those rights judicially and, if necessary, militarily; and undergird the former slaves’ new status with education, employment, land, and other resources, to be supplied by experimental government agencies. Douglass objected to what he considered an unseemly willingness to reconcile with former Confederates who failed to sincerely repudiate secession and slavery. He expressed disgust, for example, at the “bombastic laudation” accorded to Robert E. Lee upon the general’s death in 1870. Blight calls attention to a speech resonant with current controversies:

We are sometimes asked in the name of patriotism to forget the merits of [the Civil War], and to remember with equal admiration those who struck at the nation’s life, and those who struck to save it—those who fought for slavery and those who fought for liberty … May my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth if I forget the difference between the parties to that … bloody conflict.

The progressive tradition of championing Douglass runs deeper, not surprisingly, than the conservative adoption of him. As an abolitionist, a militant antislavery Republican, and an advocate for women’s rights, he allied himself with three of the greatest dissident progressive formations in American history. Activists on the left should feel comfortable seeking to appropriate the luster of his authority for many of their projects—solicitude for refugees, the elevation of women, the advancement of unfairly marginalized racial minorities. No dictum has been more ardently repeated by progressive dissidents than his assertion that “if there is no struggle there is no progress … Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.”

But certain aspects of Douglass’s life would, if more widely known, cause problems for many of his contemporary admirers on the left, a point nicely made in Blight’s biography as well as in Waldo E. Martin Jr.’s The Mind of Frederick Douglass. A Republican intra-party contest in an 1888 congressional election in Virginia pitted John Mercer Langston, a progressive black jurist (who had served as the first dean of Howard University Law School), against R. W. Arnold, a white conservative sponsored by a white party boss (who was a former Confederate general). Douglass supported Arnold, and portrayed his decision as high-minded. “The question of color,” he said, “should be entirely subordinated to the greater questions of principles and party expediency.” In fact, what had mainly moved Douglass was personal animosity; he and Langston had long been bitter rivals. Langston was hardly a paragon, but neither was Douglass. Sometimes he could be a vain, selfish, opportunistic jerk, capable of subordinating political good to personal pique.

Douglass promised that he would never permit his desire for a government post to mute his anti-racism. He broke that promise. When Hayes nominated him to be D.C. marshal, the duties of the job were trimmed. Previously the marshal had introduced dignitaries on state occasions. Douglass was relieved of that responsibility. Racism was the obvious reason for the change, but Douglass disregarded the slight and raised no objection. Some observers derided him for his acquiescence. He seemed to think that the benefit to the public of seeing a black man occupy the post outweighed the benefit that might be derived from staging yet another protest. But especially as he aged, Douglass lapsed into the unattractive habit of conflating what would be good for him with what would be good for blacks, the nation, or humanity. In this instance, his detractors were correct: He had permitted himself to be gagged by the prospect of obtaining a sinecure.

Douglass was also something of an imperialist. He accepted diplomatic positions under Presidents Ulysses S. Grant, in 1871, and Benjamin Harrison, in 1889, that entailed assisting the United States in pressuring Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic) to allow itself to become annexed and Haiti to cede territory. Douglass acted with good intentions, aiming to stabilize and elevate these black Caribbean countries by tying them to the United States in its slavery-free, post–Civil War incarnation. He liked the idea of Santo Domingo becoming a new state, thereby adding to the political muscle in America of people of African descent, a prospect that frightened or disgusted some white supremacists. When Douglass felt that his solicitude for people of color in the Caribbean was being decisively subordinated to exploitative business and militaristic imperatives, he resigned. But here again, Douglass demonstrated (along with a sometimes condescending attitude toward his Caribbean hosts) a yearning for power, prestige, and recognition from high political authorities that confused and diluted his more characteristic ideological impulses.

Douglass is entitled to and typically receives an honored place in any pantheon dedicated to heroes of black liberation. He also poses problems, however, for devotees of certain brands of black solidarity. White abolitionists were key figures in his remarkable journey to national and international prominence. Without their assistance, he would not have become the symbol of oppressed blackness in the minds of antislavery whites, and without the prestige he received from his white following, he would not have become black America’s preeminent spokesman. That whites were so instrumental in furthering Douglass’s career bothers black nationalists who are haunted by the specter of white folks controlling or unduly influencing putative black leaders.

Douglass’s romantic life has stirred related unease, a subject Blight touches on delicately, exhibiting notable interest in and sympathy for his hero’s first wife. A freeborn black woman, Anna Murray helped her future husband escape enslavement and, after they married, raised five children with him and dutifully maintained households that offered respite between his frequent, exhausting bouts of travel. Their marriage seemed to nourish them both in certain respects, but was profoundly lacking in others. Anna never learned to read or write, which severely limited the range of experience that the two of them could share. Two years after Anna died in 1882, Douglass married Helen Pitts, a Mount Holyoke College–educated white former abolitionist 20 years his junior. They tried to keep the marriage quiet; even his children were unaware of it until the union was a done deal. But soon news of it emerged and controversy ensued. The marriage scandalized many whites, including Helen’s father, who rejected his daughter completely. But the marriage outraged many blacks as well. The journalist T. Thomas Fortune noted that “the colored ladies take [Douglass’s marriage] as a slight, if not an insult, to their race and their beauty.” Many black men were angered, too. As one put it, “We have no further use for [Douglass] as a leader. His picture hangs in our parlor, we will hang it in the stable.” For knowledgeable black nationalists, Douglass’s second marriage continues to vex his legacy. Some give him a pass for what they perceive as an instance of apostasy, while others remain unforgiving.

That Douglass is celebrated so widely is a tribute most of all to the caliber and courage of his work as an activist, a journalist, a memoirist, and an orator. It is a testament as well to those, like Blight, who have labored diligently to preserve the memory of his extraordinary accomplishments. Ironically, his popularity is also due to ignorance. Some who commend him would probably cease doing so if they knew more about him. Frederick Douglass was a whirlwind of eloquence, imagination, and desperate striving as he sought to expose injustice and remedy its harms. All who praise him should know that part of what made him so distinctive are the tensions—indeed the contradictions—that he embraced.

This article appears in the December 2018 print edition with the headline “The Confounding Truth About Frederick Douglass.”

His champions now span the ideological spectrum, but left and right miss the tensions in his views.

DECEMBER 2018 ISSUE

Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom

Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom

BY DAVID W. BLIGHT SIMON & SCHUSTER

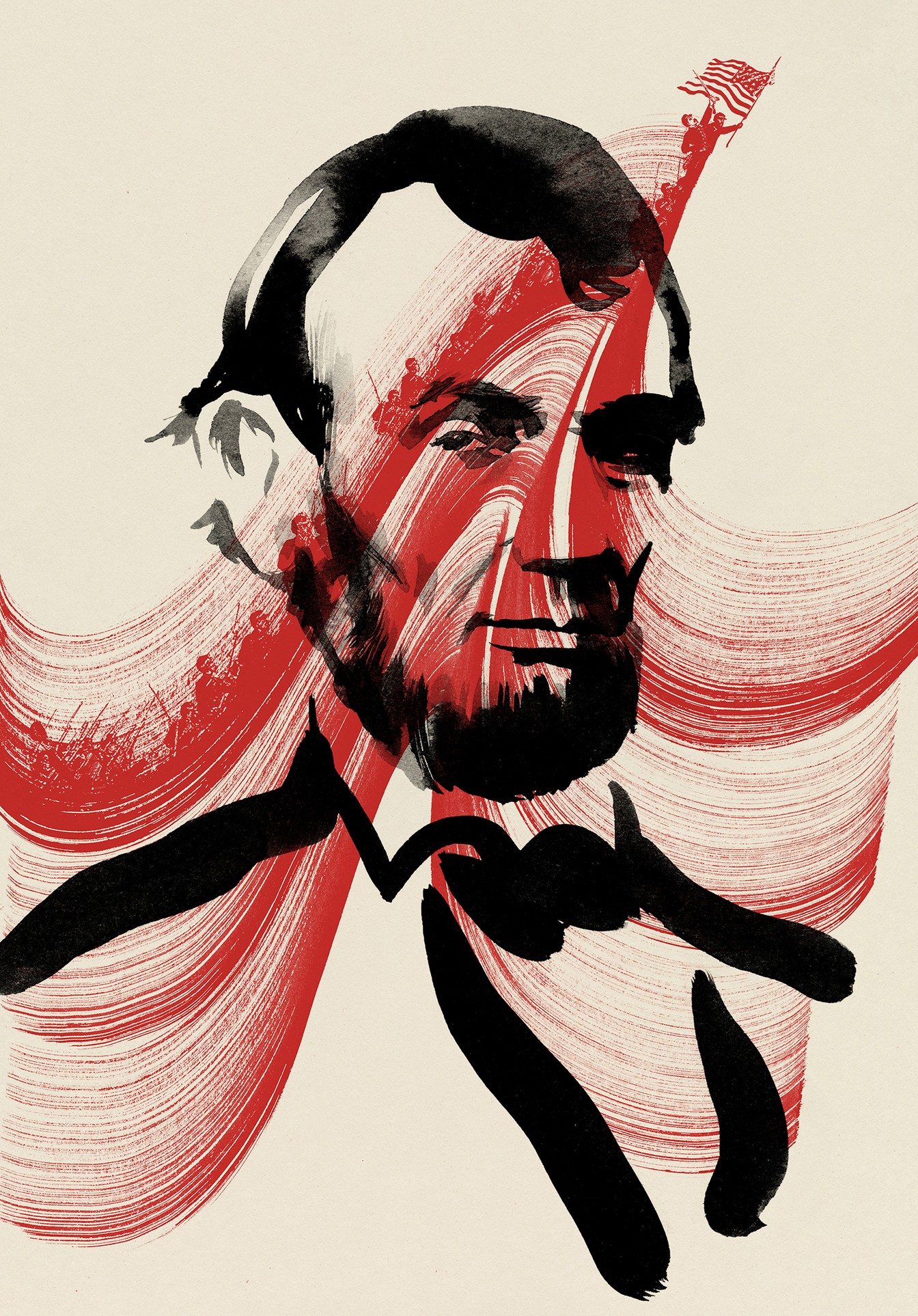

It is difficult to imagine a more remarkable story of self-determination and advancement than the life of Frederick Douglass. Emblematic of the depths from which he rose is the pall of uncertainty that shrouded his origins. For a long time he believed that he had been born in 1817. Then, in 1877, during a visit to a former master in Maryland, Douglass was told that he had actually been born in 1818. Douglass could barely recall his mother, who had been consigned to different households from the one where her baby lived. And he never discovered the identity of his father, who was likely a white man. “Genealogical trees,” Douglass mordantly observed, “do not flourish among slaves.”![]() ARSH RAZIUDDIN

ARSH RAZIUDDIN

Douglass fled enslavement in 1838, and with the assistance of abolitionists, he cultivated his prodigious talents as an orator and a writer. He produced a score of extraordinary speeches. The widely anthologized “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?,” delivered in 1852, is the most damning critique of American hypocrisy ever uttered:

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? … a day that reveals to him … the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham … your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery … There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour.”

He wrote analyses of court opinions that deservedly appear in constitutional-law casebooks. He published many arresting columns in magazines and newspapers, including several that he started. He also wrote three exceptional memoirs, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845), My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881). The most celebrated black man of his era, Douglass became the most photographed American of any race in the 19th century. He was the first black person appointed to an office requiring senatorial confirmation; in 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes nominated him to be the marshal of the District of Columbia.

It is difficult to imagine a more remarkable story of self-determination and advancement than the life of Frederick Douglass. Emblematic of the depths from which he rose is the pall of uncertainty that shrouded his origins. For a long time he believed that he had been born in 1817. Then, in 1877, during a visit to a former master in Maryland, Douglass was told that he had actually been born in 1818. Douglass could barely recall his mother, who had been consigned to different households from the one where her baby lived. And he never discovered the identity of his father, who was likely a white man. “Genealogical trees,” Douglass mordantly observed, “do not flourish among slaves.”

Douglass fled enslavement in 1838, and with the assistance of abolitionists, he cultivated his prodigious talents as an orator and a writer. He produced a score of extraordinary speeches. The widely anthologized “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?,” delivered in 1852, is the most damning critique of American hypocrisy ever uttered:

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? … a day that reveals to him … the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham … your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery … There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour.”

He wrote analyses of court opinions that deservedly appear in constitutional-law casebooks. He published many arresting columns in magazines and newspapers, including several that he started. He also wrote three exceptional memoirs, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845), My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881). The most celebrated black man of his era, Douglass became the most photographed American of any race in the 19th century. He was the first black person appointed to an office requiring senatorial confirmation; in 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes nominated him to be the marshal of the District of Columbia.

Throughout his life, however, Douglass repeatedly fell victim to the brutalizations and insults commonly experienced by African Americans of his time. As a slave, he suffered at the hands of a vicious “nigger breaker” to whom he was rented. He fled to the “free” North, only to have his work as a maritime caulker thwarted by racist white competitors. As a traveling evangelist for abolitionism, he was repeatedly ejected from whites-only railroad cars, restaurants, and lodgings. When he died, an admiring obituary in The New York Times suggested that Douglass’s “white blood” accounted for his “superior intelligence.” After his death, his reputation declined precipitously alongside the general standing of African Americans in the age of Jim Crow.

My Race Problem RANDALL KENNEDY

Frederick Douglass: An Appeal to Congress for Impartial Suffrage FREDERICK DOUGLASS

Frederick Douglass: American Lion TA-NEHISI COATES

Now everyone wants a piece of Frederick Douglass. When a statue memorializing him was unveiled at the United States Capitol in 2013, members of the party of Paul Ryan and Mitch McConnell sported buttons that read frederick douglass was a republican. More recently, the Republican National Committee issued a statement joining President Donald Trump “in honoring Douglass’ lifelong dedication to the principles that define [the Republican] Party and enrich our nation.” Across the ideological divide, former President Barack Obama has lauded Douglass, as has the leftist intellectual Cornel West. New books about Douglass have appeared with regularity of late, and are now joined by David W. Blight’s magnificently expansive and detailed Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom.

A history professor at Yale who has long been a major contributor to scholarship on Douglass, slavery, and the Civil War, Blight portrays Douglass unequivocally as a hero while also revealing his weaknesses. Blight illuminates important facets of 19th-century political, social, and cultural life in America, including the often overlooked burdens borne by black women. At the same time, he speaks to urgent, contemporary concerns such as Black Lives Matter. Given the salience of charges of cultural misappropriation, griping about his achievement would be unsurprising: Blight is a white man who has written the leading biography of the most outstanding African American of the 19th century. His sensitive, careful, learned, creative, soulful exploration of Douglass’s grand life, however, transcends his own identity.

In the wake of Douglass’s death in 1895, it was African Americans who kept his memory alive. Booker T. Washington wrote a biography in 1906. The historian Benjamin Quarles wrote an excellent study in 1948. White historians on the left also played a key role in protecting Douglass from oblivion, none more usefully than Philip Foner, a blacklisted Marxist scholar (and uncle of the great historian Eric Foner), whose carefully edited collection of Douglass’s writings remains essential reading. But in “mainstream”—white, socially and politically conventional—circles, Douglass was widely overlooked. In 1962, the esteemed literary critic Edmund Wilson published Patriotic Gore: Studies in the Literature of the American Civil War, a sprawling (and lavishly praised) commentary on writings famous and obscure that omitted Douglass, and virtually all the other black literary figures of the period.

Keenly attuned to the politics of public memory, Blight shows that the current profusion of claims on Douglass’s legacy bears close scrutiny: Claimants have a way of overlooking features of his complex persona that would be embarrassing for them to acknowledge. Conservatives praise his individualism, which sometimes verged on social Darwinism. They also herald Douglass’s stress on black communal self-help, his antagonism toward labor unions, and his strident defense of men’s right to bear arms. They tiptoe past his revolutionary rage against the United States during his early years as an abolitionist. “I have no patriotism,” he thundered in 1847. “I cannot have any love for this country … or for its Constitution. I desire to see it overthrown as speedily as possible.” Radical as to ends, he was also radical as to means. He justified the violence deployed when a group of abolitionists tried to liberate a fugitive slave from a Boston jail and killed a deputy U.S. marshal in the process. Similarly, he assisted and praised John Brown, the insurrectionist executed for murder and treason in Virginia in 1859.

Many conservatives who claim posthumous alliance with Douglass would abandon him if they faced the prospect of being publicly associated with the central features of his ideology. After all, he championed the creation of a strong post–Civil War federal government that would extend civil and political rights to the formerly enslaved; protect those rights judicially and, if necessary, militarily; and undergird the former slaves’ new status with education, employment, land, and other resources, to be supplied by experimental government agencies. Douglass objected to what he considered an unseemly willingness to reconcile with former Confederates who failed to sincerely repudiate secession and slavery. He expressed disgust, for example, at the “bombastic laudation” accorded to Robert E. Lee upon the general’s death in 1870. Blight calls attention to a speech resonant with current controversies:

We are sometimes asked in the name of patriotism to forget the merits of [the Civil War], and to remember with equal admiration those who struck at the nation’s life, and those who struck to save it—those who fought for slavery and those who fought for liberty … May my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth if I forget the difference between the parties to that … bloody conflict.

The progressive tradition of championing Douglass runs deeper, not surprisingly, than the conservative adoption of him. As an abolitionist, a militant antislavery Republican, and an advocate for women’s rights, he allied himself with three of the greatest dissident progressive formations in American history. Activists on the left should feel comfortable seeking to appropriate the luster of his authority for many of their projects—solicitude for refugees, the elevation of women, the advancement of unfairly marginalized racial minorities. No dictum has been more ardently repeated by progressive dissidents than his assertion that “if there is no struggle there is no progress … Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.”

But certain aspects of Douglass’s life would, if more widely known, cause problems for many of his contemporary admirers on the left, a point nicely made in Blight’s biography as well as in Waldo E. Martin Jr.’s The Mind of Frederick Douglass. A Republican intra-party contest in an 1888 congressional election in Virginia pitted John Mercer Langston, a progressive black jurist (who had served as the first dean of Howard University Law School), against R. W. Arnold, a white conservative sponsored by a white party boss (who was a former Confederate general). Douglass supported Arnold, and portrayed his decision as high-minded. “The question of color,” he said, “should be entirely subordinated to the greater questions of principles and party expediency.” In fact, what had mainly moved Douglass was personal animosity; he and Langston had long been bitter rivals. Langston was hardly a paragon, but neither was Douglass. Sometimes he could be a vain, selfish, opportunistic jerk, capable of subordinating political good to personal pique.

Douglass promised that he would never permit his desire for a government post to mute his anti-racism. He broke that promise. When Hayes nominated him to be D.C. marshal, the duties of the job were trimmed. Previously the marshal had introduced dignitaries on state occasions. Douglass was relieved of that responsibility. Racism was the obvious reason for the change, but Douglass disregarded the slight and raised no objection. Some observers derided him for his acquiescence. He seemed to think that the benefit to the public of seeing a black man occupy the post outweighed the benefit that might be derived from staging yet another protest. But especially as he aged, Douglass lapsed into the unattractive habit of conflating what would be good for him with what would be good for blacks, the nation, or humanity. In this instance, his detractors were correct: He had permitted himself to be gagged by the prospect of obtaining a sinecure.

Douglass was also something of an imperialist. He accepted diplomatic positions under Presidents Ulysses S. Grant, in 1871, and Benjamin Harrison, in 1889, that entailed assisting the United States in pressuring Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic) to allow itself to become annexed and Haiti to cede territory. Douglass acted with good intentions, aiming to stabilize and elevate these black Caribbean countries by tying them to the United States in its slavery-free, post–Civil War incarnation. He liked the idea of Santo Domingo becoming a new state, thereby adding to the political muscle in America of people of African descent, a prospect that frightened or disgusted some white supremacists. When Douglass felt that his solicitude for people of color in the Caribbean was being decisively subordinated to exploitative business and militaristic imperatives, he resigned. But here again, Douglass demonstrated (along with a sometimes condescending attitude toward his Caribbean hosts) a yearning for power, prestige, and recognition from high political authorities that confused and diluted his more characteristic ideological impulses.

Douglass is entitled to and typically receives an honored place in any pantheon dedicated to heroes of black liberation. He also poses problems, however, for devotees of certain brands of black solidarity. White abolitionists were key figures in his remarkable journey to national and international prominence. Without their assistance, he would not have become the symbol of oppressed blackness in the minds of antislavery whites, and without the prestige he received from his white following, he would not have become black America’s preeminent spokesman. That whites were so instrumental in furthering Douglass’s career bothers black nationalists who are haunted by the specter of white folks controlling or unduly influencing putative black leaders.

Douglass’s romantic life has stirred related unease, a subject Blight touches on delicately, exhibiting notable interest in and sympathy for his hero’s first wife. A freeborn black woman, Anna Murray helped her future husband escape enslavement and, after they married, raised five children with him and dutifully maintained households that offered respite between his frequent, exhausting bouts of travel. Their marriage seemed to nourish them both in certain respects, but was profoundly lacking in others. Anna never learned to read or write, which severely limited the range of experience that the two of them could share. Two years after Anna died in 1882, Douglass married Helen Pitts, a Mount Holyoke College–educated white former abolitionist 20 years his junior. They tried to keep the marriage quiet; even his children were unaware of it until the union was a done deal. But soon news of it emerged and controversy ensued. The marriage scandalized many whites, including Helen’s father, who rejected his daughter completely. But the marriage outraged many blacks as well. The journalist T. Thomas Fortune noted that “the colored ladies take [Douglass’s marriage] as a slight, if not an insult, to their race and their beauty.” Many black men were angered, too. As one put it, “We have no further use for [Douglass] as a leader. His picture hangs in our parlor, we will hang it in the stable.” For knowledgeable black nationalists, Douglass’s second marriage continues to vex his legacy. Some give him a pass for what they perceive as an instance of apostasy, while others remain unforgiving.

That Douglass is celebrated so widely is a tribute most of all to the caliber and courage of his work as an activist, a journalist, a memoirist, and an orator. It is a testament as well to those, like Blight, who have labored diligently to preserve the memory of his extraordinary accomplishments. Ironically, his popularity is also due to ignorance. Some who commend him would probably cease doing so if they knew more about him. Frederick Douglass was a whirlwind of eloquence, imagination, and desperate striving as he sought to expose injustice and remedy its harms. All who praise him should know that part of what made him so distinctive are the tensions—indeed the contradictions—that he embraced.

This article appears in the December 2018 print edition with the headline “The Confounding Truth About Frederick Douglass.”