Group’s executive director had been scheduled to unveil the report in Hong Kong but was barred from entering at the airport on Sunday

Other governments, including the US and UK, are criticised for not finding ‘a common voice’ on China’s repression

Jodi Xu Klein in New York Published:15 Jan, 2020

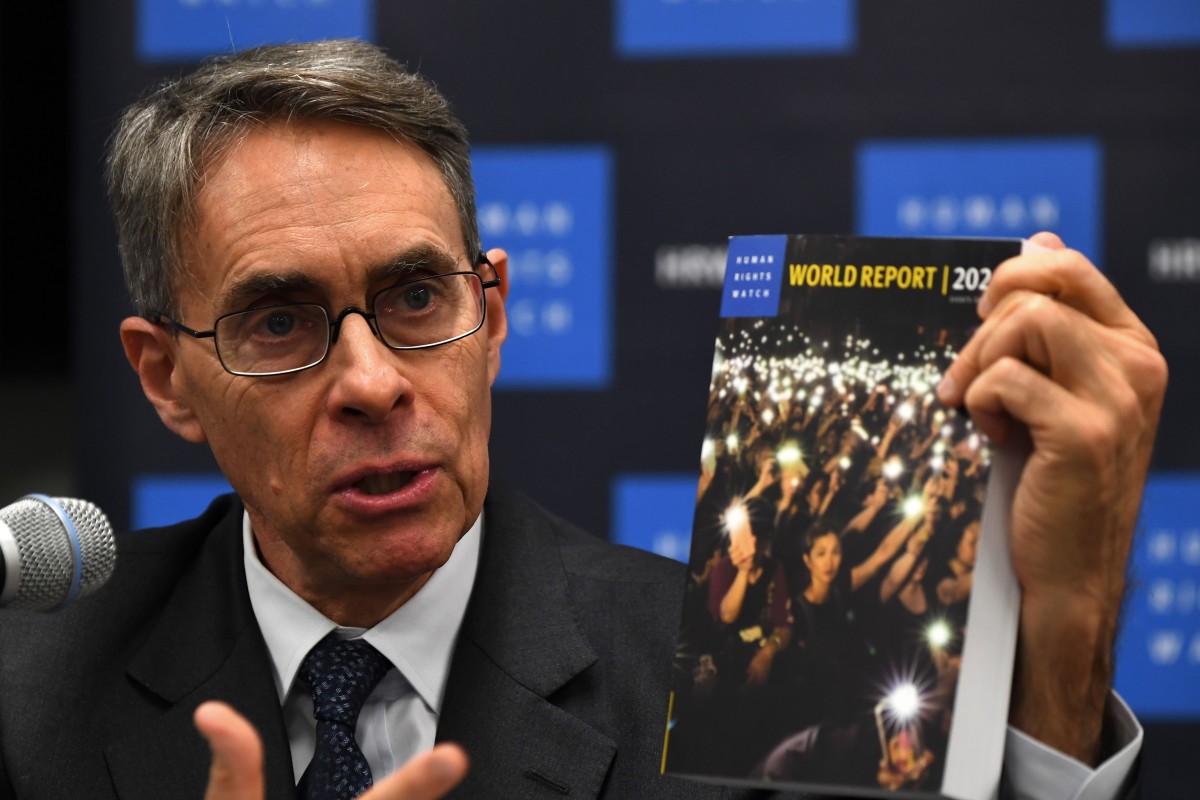

Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch, introduces the group’s 2020 World Report at UN headquarters in New York on Tuesday. Photo: AFP

The Chinese government fears “people’s desire for democracy” and its repression of human rights is “an existential threat to the world”, the investigative and advocacy group Human Rights Watch said on Tuesday at the launch of its World Report 2020 in New York.

The release of the annual report had already made headlines when immigration officials at the Hong Kong airport turned away the group’s executive director, Kenneth Roth, without explanation on Sunday. He had been scheduled to unveil the report in the city on Wednesday.

“We’d hoped to hold this event in Hong Kong, but Chinese government had a different idea,” Roth said on Tuesday at the United Nations headquarters.

“Beijing claimed the report had instigated the Hong Kong people’s movement for democracy,” Roth said. “The stance by Beijing is insulting to Hong Kong. It shows Chinese government’s fear of people’s desire for democracy.”

The Chinese government has long suppressed human rights at home. Now it is trying to suppress global efforts to defend human rights. The rights of everyone, and our future, are at stake. That's the theme of this years's @HRW World Report. https://t.co/9ahp2wVt2h pic.twitter.com/KPybJyg0mY — Kenneth Roth (@KenRoth) January 14, 2020This year’s report, a 652-page review of human rights practices in nearly 100 countries, focused on the Chinese government’s role in the world.

The global system for protecting human rights is under threat from China under President Xi Jinping, the group said.

“It seems the Chinese government sees human rights as an existential threat. But their stance against human rights is an existential threat to the world,” Roth said.

The report cited China’s continued forced detention of some 1 million Uygurs and other Muslims in the far western autonomous region of Xinjiang.

Pompeo stresses Hong Kong autonomy, urges slamming China over Uygur abuse

The Chinese authorities have further expanded their assault on freedom of expression, including arresting journalists and prosecuting activists, Roth said.

He also said that without proper defences, the world could be threatened by “a dystopian future in which no one is beyond the reach of Chinese censors”.

China has embarked on a global promotional campaign to blunt criticism of its human rights record and has received the support of governments in Russia, Syria, North Korea, Myanmar, Belarus and Saudi Arabia.

More concerning, said the report, is that “several important governments have been missing in action”.

“That included the US and the European Union, which has been diverted by Brexit, and find it difficult to find a common voice in human rights.”

Hong Kong immigration denies entry to Human Rights Watch executive director

“Others, like Pakistan, are simply bought off. When the prime minister of Pakistan visited Beijing, he had nothing to say regarding Xinjiang.”

“The Trump administration has at times stood up to China, including imposing sanctions against China in October,” said Roth. “But more often, [US President Donald] Trump has praised Xi Jinping.”

China is also silencing business communities by threatening their access to the massive Chinese market, which accounts for about 16 per cent of the global GDP, Roth said.

The government has also targeted academic freedom worldwide, the report said. In Australia, Canada, the UK and the US, pro-Beijing students have sought to shut down controversial debates about China.

Why China’s crackdown on academic freedom will backfire

Tuesday’s news conference at the United Nations Correspondents Association was interrupted by a Chinese official who told Roth “the report is full of prejudices and has ignored facts”.

“I completely reject the content in the report,” said Xing Jisheng, a Chinese mission representative at the UN. “Any report talking about Chinese human rights fails to be balanced and neutral.”

Roth asked for specifics about what the report got wrong.

Xing said China was a great success story because it had freed its people from poverty, to which Sophie Richardson, the China director at Human Rights Watch, responded: “The Chinese people got themselves out of poverty after the government took the boot off of their neck.”

Rally in Hong Kong to thank US for supporting the Human Rights and Democracy Act

Beijing has made the UN a primary target as it has routinely worked against proposed measures and the global human rights framework, the report said.

“The Chinese government’s attacks on human rights systems must be stopped,” Roth said. “The ascent of a global threat to rights is not unstoppable. The governments should band together.”

Roth, an American citizen, returned to the United States after being barred from entering Hong Kong at the city’s international airport on Sunday.

On December 2, Chinese foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying said the government would impose sanctions against Human Rights Watch and four other US-based non-profit groups that “played an egregious role” in the pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong.

Those remarks came after Trump signed into law the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act, which could pave the way for diplomatic action and economic sanctions against the city’s government.

Jodi Xu Klein is an award-winning business journalist with 20 years of experience. She joined the Post in 2017, after a decade based in the US reporting for The Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg. She was part of the Time Magazine team that won the Henry R. Luce Award, breaking the China SARS story

Human Rights Watch chief Kenneth Roth says barring him from Hong Kong is ‘sad and troubling’ reflection of Beijing pressure

The group’s executive director said immigration officials at the airport refused him entry to Hong Kong without explanation

Roth plans to unveil human rights report, which is highly critical of China, in New York instead, as city officials refuse to comment on case

Lilian Cheng andDanny Mok 12 Jan, 2020

Human Rights Watch executive director Kenneth Roth had visited Hong Kong multiple times in the past. Photo: Sam Tsang

The head of Human Rights Watch who was barred from entering Hong Kong said on Monday he was saddened at how the city had deteriorated under pressure from Beijing, as he vowed to unveil his report in New York instead.

Kenneth Roth, the group’s executive director and an American citizen, returned to the United States after Hong Kong immigration authorities turned him away at the city's international airport on Sunday without explanation, according to the organisation.

He had planned to visit the city to launch the New York-based group’s “World Report 2020”, which includes a lead essay on the Chinese government’s “assault” on the international human rights system.

Hong Kong immigration denies entry to Human Rights Watch executive director

An Immigration Department spokeswoman said it would not comment on individual cases.

She added that when handling cases, the department would, in accordance with the laws and immigration policies, fully consider all relevant factors and circumstances of the case before deciding whether the entry should be allowed or not.

Roth said: “I had hoped to spotlight Beijing’s deepening assault on international efforts to uphold human rights. The refusal to let me enter Hong Kong vividly illustrates the problem.”

Roth, who had flown in from New York, later wrote on Twitter: “Despite my probing, the Hong Kong immigration authorities would say only (and repeatedly) that they were barring me for ‘immigration reasons’. They wouldn’t even own up to the real reason.”

“It's sad and troubling how quickly things have deteriorated under pressure from Beijing,” he added.

“Trying to silence the human rights messenger shows a determination to flout, not uphold, human rights standards.”

The group was expected to release its 652-page report at a news conference in Hong Kong on Wednesday. The report reviews human rights practices in nearly 100 countries.

Roth’s essay says the Chinese government is undermining the global system for enforcing human rights.

Kenneth Roth had planned to release the group’s report on Wednesday. Photo: Sam Tsang

On his return to the US on Monday, Roth revealed he would launch the report at a news conference at the United Nations in New York on Tuesday “given that the authorities blocked me from entering Hong Kong.”

On December 2, Beijing’s foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying said the Chinese government would impose sanctions against Human Rights Watch and four other US-based non-profit groups that “played an egregious role” in the disturbances in Hong Kong, in its response to Washington’s endorsement of the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act , which could pave the way for diplomatic action and economic sanctions against the city’s government.

The other groups were the National Endowment for Democracy, the National Democratic Institute for International Affairs, the International Republican Institute and Freedom House.

The next day Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor said her government would follow up on the sanctions announcement.

Roth has visited Hong Kong several times, including to release a report on gender discrimination in the Chinese job market in April 2018.

US author who documented Hong Kong protests says he was barred from city

The group also listed a number of other visitors who had been denied entry by Hong Kong immigration authorities, including a US photographer [Matthew Connors] who documented Hong Kong protests in January, US academic Dan Garrett last September, and United Kingdom-based founder of Hong Kong Watch Benedict Rogers in October 2017.

“This disappointing action is yet another sign that Beijing is tightening its oppressive grip on Hong Kong and further restricting the limited freedom Hong Kong people enjoy under ‘one country, two systems,’” Roth said, referring to the principle under which Hong Kong is governed.

Earlier this month, Human Rights Watch co-wrote an open letter to Lam, urging her to set up an independent commission of inquiry to investigate alleged excessive use of force by police in the more than seven months of anti-government protests in Hong Kong.

“An independent commission of inquiry is the first step to addressing the serious human rights violations against protesters since June,” said Sophie Richardson, China director at Human Rights Watch. The European Union also weighed in on the controversy. In a statement, European Commission spokeswoman Virginie Battu-Henriksson said denying entry to Roth “raises serious questions over Hong Kong’s traditions of openness and respect for fundamental rights and freedoms, including freedom of expression”.

“These principles are enshrined in the Basic Law and the Hong Kong Bill of Rights,” Battu-Henriksson said. “These principles are an integral part of Hong Kong's continuing success and we expect them to be upheld.”

This article appeared in the South China Morning Post print edition as: Barring me is sad and troubling, US rights leader says

Human rights

Hong Kong protests

Lilian Cheng

Lilian joined the Post in 2019 as senior reporter covering Hong Kong’s housing, land and development policies. She started her career at Ming Pao in 2010 and was then a principal reporter at i-Cable News. She has won awards for her reporting on a major discovery of Sung relics near the planned To Kwa Wan railway station.

Hong Kong protests: High Court test for warrants that let police search phones

Photographer whose unlawful assembly charges were dropped in November applies for judicial review

Writ states the documents effectively allowed ‘any police officer to search and seize the entire digital contents of [his] mobile phone’

Ng Kang-chung

Published: 11:30pm, 13 Jan, 2020

Protesters and police have repeatedly clashed on Hong Kong

streets since June. Photo: Sam Tsang

A photographer who briefly faced charges over an anti-government protest has sought to challenge the legality of two court-issued warrants which allowed Hong Kong police to access his mobile phone and other digital devices.

Lee Wing-ho, 22, applied for a judicial review seeking that the High Court declare magistrates acted unlawfully in granting the warrants, and breached his constitutional right to freedom and privacy of communication.

In a writ filed on Monday, Lee claimed the warrants were too general, effectively authorising “any police officer to search and seize the entire digital contents of [his] mobile phone … without any limitation or conditions whatsoever imposed”.

“The magistrates have … failed to carry out the judicial gatekeeping function,” his writ read, adding that the subsequent police action to access the contents of his devices was an “oppressive, arbitrary or unconstitutional action”.

The writ was filed at the High Court on Monday. Photo: Roy Issa

Lee was arrested for unlawful assembly on Nathan Road during an anti-government protest in Mong Kok on August 3 last year. Upon his arrest, officers seized property including his mobile phone and some digital storage cards. He did not find out warrants had been issued for police to access his devices until October 23, when his case was about to go to court.

He also found out that the warrants would authorise police to enter an office at the force’s headquarters in Wan Chai where his devices were stored, along with about 50 phones and devices seized from other arrestees.

In his writ, Lee argued: “This is a chilling threat at a very fundamental level. A search warrant obtained by the police to access objects inside a police building is an abuse of process, an artifice.”

Top judge sets up task force to speed up dealing with protest cases

14 Jan 2020

“The police officers were given unchecked power to sift, copy, save, and retain any information they wished throughout that period, including new messages and communications.”

Phone-related privacy concerns were raised last month after pro-democracy activist Joshua Wong Chi-fung, who was arrested in August over a protest in June, questioned whether police had abused their power to “hack” his password-protected phone after the prosecution in his case admitted instant messaging records as evidence. Wong said he had not given police the password.

Police later clarified that the procedure was conducted under a magistrate-issued search warrant.

Anti-government protests have rocked Hong Kong for more than seven months. Initially sparked by an extradition bill, which has since been withdrawn, the movement has broadened into a push for greater democracy and police accountability. Protesters and police have repeatedly clashed violently on city streets, and thousands have been arrested.

Dozens detained by police after march against parallel traders in Hong Kong’s Sheung Shui

During last week’s Legislative Council meeting, Secretary for Security John Lee Ka-chiu disclosed that police had seized more than 3,700 mobile phones used by protesters in the last several months of protests.

Lee maintained a “digital forensic examination” of the devices would only be conducted after getting a search warrant from the court.

“From June to November 2019, police processed 1,429 cases that involved mobile phones as evidence,” Lee told legislators at the meeting. “Among those cases, 3,721 mobile phones belonging to arrested persons or suspects were involved, and the relevant cases were all processed with search warrants issued by the court.”

Neither the police nor the judiciary replied to requests for comment.

A photographer who briefly faced charges over an anti-government protest has sought to challenge the legality of two court-issued warrants which allowed Hong Kong police to access his mobile phone and other digital devices.

Lee Wing-ho, 22, applied for a judicial review seeking that the High Court declare magistrates acted unlawfully in granting the warrants, and breached his constitutional right to freedom and privacy of communication.

In a writ filed on Monday, Lee claimed the warrants were too general, effectively authorising “any police officer to search and seize the entire digital contents of [his] mobile phone … without any limitation or conditions whatsoever imposed”.

“The magistrates have … failed to carry out the judicial gatekeeping function,” his writ read, adding that the subsequent police action to access the contents of his devices was an “oppressive, arbitrary or unconstitutional action”.

The writ was filed at the High Court on Monday. Photo: Roy Issa

Lee was arrested for unlawful assembly on Nathan Road during an anti-government protest in Mong Kok on August 3 last year. Upon his arrest, officers seized property including his mobile phone and some digital storage cards. He did not find out warrants had been issued for police to access his devices until October 23, when his case was about to go to court.

He also found out that the warrants would authorise police to enter an office at the force’s headquarters in Wan Chai where his devices were stored, along with about 50 phones and devices seized from other arrestees.

In his writ, Lee argued: “This is a chilling threat at a very fundamental level. A search warrant obtained by the police to access objects inside a police building is an abuse of process, an artifice.”

Top judge sets up task force to speed up dealing with protest cases

14 Jan 2020

“The police officers were given unchecked power to sift, copy, save, and retain any information they wished throughout that period, including new messages and communications.”

Phone-related privacy concerns were raised last month after pro-democracy activist Joshua Wong Chi-fung, who was arrested in August over a protest in June, questioned whether police had abused their power to “hack” his password-protected phone after the prosecution in his case admitted instant messaging records as evidence. Wong said he had not given police the password.

Police later clarified that the procedure was conducted under a magistrate-issued search warrant.

Anti-government protests have rocked Hong Kong for more than seven months. Initially sparked by an extradition bill, which has since been withdrawn, the movement has broadened into a push for greater democracy and police accountability. Protesters and police have repeatedly clashed violently on city streets, and thousands have been arrested.

Dozens detained by police after march against parallel traders in Hong Kong’s Sheung Shui

During last week’s Legislative Council meeting, Secretary for Security John Lee Ka-chiu disclosed that police had seized more than 3,700 mobile phones used by protesters in the last several months of protests.

Lee maintained a “digital forensic examination” of the devices would only be conducted after getting a search warrant from the court.

“From June to November 2019, police processed 1,429 cases that involved mobile phones as evidence,” Lee told legislators at the meeting. “Among those cases, 3,721 mobile phones belonging to arrested persons or suspects were involved, and the relevant cases were all processed with search warrants issued by the court.”

Neither the police nor the judiciary replied to requests for comment.

Hong Kong / Politics

Hong Kong / PoliticsHong Kong protesters have been receiving training from foreign forces, city’s security chief says, while also revealing more than 3,700 phones were seized and broken into

John Lee said no evidence linked recent seizures of weapons and bombs to overseas terrorist organisations, but suggested some protesters were not acting alone

Opposition legislators said making such claims without providing proof was irresponsible

Natalie Wong,Sum Lok-kei,Ng Kang-chung

Published: 10:03pm, 8 Jan, 2020

“We don’t believe that a handful of unorganised rioters could orchestrate such events,” said John Lee. Photo: Xiaomei Chen

Hong Kong’s security chief raised concerns on Wednesday that some anti-government protesters received training from “non-local” individuals to fuel the social unrest plaguing the city for seven months.

John Lee Ka-chiu became the first top official to go beyond speculation about the involvement of foreign forces to cite intelligence and the well-planned nature of the protests in making the allegation.

He said there was no evidence linking a recent, protest-related spate of weapon and bomb seizures by police to overseas terrorist organisations, but suggested some protesters were not acting on their own.

Lee also revealed police had seized 3,721 mobile phones from protesters in the first five months of unrest and had them broken into to read the contents.

John Lee said police would only access protesters’ phones after getting a court-ordered warrant. Photo: Edward Wong

Responding to a pro-establishment lawmaker’s question in the Legislative Council on Wednesday, the secretary for security said: “Based on the rioters’ acts, we definitely believe they received training.”

He did not name any organisation or individual, but said the assessment was based on the government’s investigation and intelligence concerning “how [protesters] were organised” and “the different versions and angles of promotional materials they have”.

“It seems that in every operation or incident, they will plan in advance with a deliberate plot in a syndicated manner,” Lee said. “In terms of resources and mobilisation, we don’t believe that a handful of unorganised rioters could orchestrate such events.”

Nobody should believe Lee’s empty accusation until he can prove his claimsAlvin Yeung, Civic Party leader

Lee added that online news had also indicated overseas groups were training individuals to join the movement.

Civic Party leader Alvin Yeung Ngok-kiu said it was extremely irresponsible for Lee to make such accusations without proof.

He said the official was no different from former city leader Leung Chun-ying, who claimed foreign interference was behind the 2014 Occupy movement, but “at the end of the day proved nothing”.

“Nobody should believe Lee’s empty accusation until he can prove his claims,” Yeung said.

Pro-democracy lawmaker Kenneth Leung, of the Professionals Guild, accused Lee of making “irresponsible and serious accusations” without evidence.

“I can’t see why creativity demonstrated by protesters has to be linked to overseas training,” he said.

But pro-Beijing lawmaker Wong Kwok-kin, who is also an adviser to the city’s leader in the Executive Council, backed Lee.

Wong said he was convinced it would be impossible for protests to roll on for months without foreign manipulation.

Lee revealed in the same meeting that police had processed mobile phones belonging to arrested protesters from June to November with search warrants issued by the courts.

Kenneth Leung criticised Lee’s “irresponsible and serious accusations”. Photo: Winson Wong

“Police will only conduct a digital forensic examination on mobile phones after obtaining court warrants,” he said, dismissing concerns about abuse of power.

Activist Joshua Wong Chi-fung – who was arrested in August in connection with a protest in June – had questioned whether police abused their power by hacking into his mobile phone. He found that some instant messaging records from his locked phone had been admitted as evidence by the prosecution.

Wong said in December he had not given up his password during his arrest. Police clarified that it was conducted under a magistrate-issued search warrant.

Opposition lawmaker Charles Mok called for more guidelines to prevent possible abuse.

“We are talking about [a lot of] phones,” Mok said. “You break into the phones and read the contents, all contents, whether they are related to the cases being investigated or not. And no one can know if the phones will have spyware installed after being seized.”

Icarus Wong Ho-yin, a spokesman for Civil Rights Observer, a concern group, agreed.

“It seems it has now become a casual procedure that officers will seize an arrestee’s phone and check its contents,” he said.

Dozens detained by police after march against parallel traders in Hong Kong’s Sheung Shui

He added the risk of possible abuse was getting higher as police had resorted to making mass arrests recently.

“We have heard of cases of officers threatening people stopped on the street for questioning to hand over and unlock their phones for officers to check the contents, risking arrest if they do not comply,” Wong said.

Meanwhile, the government rejected a suggestion by the pro-Beijing camp to introduce legislation to stop demonstrators from “disguising themselves as online media workers” to make it easier for them to carry out illegal acts.

Secretary for Home Affairs Lau Kong-wah said that, despite suspected cases of protesters impersonating reporters and participating in illegal and violent acts, the government would not define what constituted a media worker with legislation and had no intention of screening journalists’ qualifications to report.

Meanwhile, riot police applied pepper spray to disperse protesters after a vigil in Sheung Tak Estate in Tseung Kwan O to mark the two-month anniversary of the death of Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) student Chow Tsz-lok.

A dozen black-clad protesters laid bricks and other large items on the road outside a car park in the estate where the vigil took place. Officers rushed in to warn participants to leave the illegal assembly, while tear gas warnings were raised.

Several protesters were later subdued on the ground at about 10.40pm and officers fired pepper spray to stop others from getting closer.

Chow fell from the car park near a police operation on November 4 and died on November 8. The circumstances of the death have not been explained.

This article appeared in the South China Morning Post print edition as: Top official suggests outsiders helped train some protesters

Sum Lok-kei

Sum Lok-kei joined the Post in 2018. He is a reporter on the Hong Kong desk.

Hong Kong / Law and Crime

Hong Kong police seized more than 3,700 mobile phones from protesters in space of five months and had devices broken into to read contents, security chief reveals

Secretary for Security John Lee dismisses concerns about potential abuse of power, maintaining the cases all satisfied court for issuing of search warrants

Lee would not comment on whether police used spyware to unlock suspects’ phones

Ng Kang-chung

Published: 8 Jan, 2020

Police processed 1,429 cases involving mobile phones as evidence from June to November, it was revealed. Photo: EPA

Hong Kong police seized more than 3,700 mobile phones from anti-government protesters in the first five months of the ongoing civil unrest and had the devices broken into to read the contents, the city’s security chief has revealed.

Secretary for Security John Lee Ka-chiu dismissed concerns about a possible abuse of power, maintaining the cases all satisfied the court for the issuing of search warrants.

Lee made the disclosure on Wednesday when responding to lawmakers’ questions on the police’s power to access the contents of mobile phones without the owners’ consent or knowledge.

“From June to November 2019, police processed 1,429 cases that involved mobile phones as evidence,” Lee told the Legislative Council meeting.

John Lee dismissed concerns about a possible abuse of power. Photo: May Tse

“Among those cases, 3,721 mobile phones belonging to arrested persons or suspects were involved, and the relevant cases were all processed with search warrants issued by the court.”

Lee said the seizure of phones was usual practice and not meant only to tackle those arrested during the social unrest, which broke out last June.

“While carrying out their responsibilities, [law enforcement agencies] may exercise the search and seizure powers conferred by relevant legislation, and seize and examine various objects of the suspected offence, including mobile phones and other similar devices,” he said.

“Police will only conduct digital forensic examination on mobile phones after obtaining court warrants. The examination and the evidence obtained will be adduced in the relevant open trials.”

Concerns were raised last month after pro-democracy activist Joshua Wong Chi-fung, who was arrested in August in connection with a protest in June, questioned whether police had abused their power to hack into his password-protected mobile phone after the prosecution admitted as evidence some instant messaging records.

Hong Kong has been in the grip of protests since June. Photo: Edmond So

Wong said he had not disclosed the phone’s password to police.

Police later clarified that the procedure was conducted under a magistrate-issued search warrant.

At Wednesday’s Legco meeting, Lee would not comment on whether police used spyware to unlock suspects’ phones.

“As the critical technologies used in the examinations are confidential, disclosing such information may reveal to criminals details of operations, thus allowing them to take advantage by undermining [law enforcement agencies’] capabilities in combating serious crimes and maintaining public safety.”

Lee also cited a 2017 case in which the court ruled that under the Police Force Ordinance, officers may seize mobile phones found on an apprehended person, but would need a warrant to examine the contents in a non-emergency situation.

The case stemmed from the arrest of a truck driver for the Civil Human Rights Front, who was held for not following police orders when he was leading the annual July 1 march in 2014.

Joshua Wong says he never gave his phone password to police. Photo: May Tse

Opposition lawmaker Charles Mok said he was shocked by Lee’s disclosure and called for more guidelines to prevent possible abuse.

“We are talking about 3,700-odd phones. That is a very big number. So far, police have arrested 6,000-odd people [in connection with the protests],” Mok said.

“You break into the phones and read the contents, all contents, whether they are related to the cases being investigated or not. And no one will even know if the phones will be installed with spyware after being seized by officers.”

Mok’s views, meanwhile, were echoed by Icarus Wong Ho-yin, spokesman for concern group Civil Rights Observer.

“It seems to me that it has now become a casual procedure that officers will seize an arrestee’s phone and check the contents,” Wong said, adding that the risk of possible abuse was rising as police had recently resorted to making mass arrests.

“We have heard of cases where officers threatened a person who was stopped on the street for questioning to hand over and unlock his phone to check the contents, or else risk being arrested. Usually, the person will give in.”

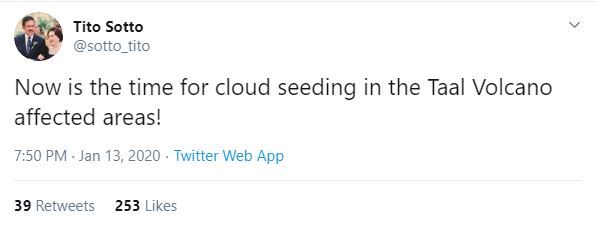

Sen. Tito Sotto III tweeting about cloud seeding in areas areas affected by the ashfall of Taal Volcano. (Screenshot by Interaksyon)

Sen. Tito Sotto III tweeting about cloud seeding in areas areas affected by the ashfall of Taal Volcano. (Screenshot by Interaksyon)