LANGUAGE OF SPACE EXPLORATION RHETORIC CAN AFFECT PUBLIC PERCEPTION OF SPACE ACTIVITIES

Would we want futuristic Mars settlements to operate like modern-day Earth towns, or could we do better?

UNDARKMAR 29, 2021 11:05:13 IST

By Joelle Renstrom

Last month, NASA’s Perseverance rover landed on the surface of Mars to much fanfare, just days after probes from the UAE and China entered orbit around the Red Planet. The surge in Martian traffic symbolizes major advancements in space exploration. It also presents an opportune moment to step back and consider not only what humans do in space, but how we do it — including the words we use to describe human activities in space.

The conversation around the language of space exploration has already begun. NASA, for instance, has been rooting out the gendered language that has plagued America’s space program for decades. Instead of using “manned” to describe human space missions, it has shifted to using gender-neutral terms like “piloted” or “crewed.” But our scrutiny of language shouldn’t stop there. Other words and phrases, particularly those that invoke capitalism or colonialism, should receive the same treatment.

To some extent, language influences the way we think and understand the world around us. A dramatic example comes from the Pirahã tribe of the Brazilian Amazon, whose language contains very few terms for describing numbers or time. A capitalist culture in which time equals money likely wouldn’t make sense to them. Similarly, language likely affects humans’ thoughts and beliefs about outer space. The words scientists and writers use to describe space exploration may influence who feels included in these endeavors — both as direct participants and as benefactors — and alter the way people interact with the cosmos.

Take, for example, John F. Kennedy’s 1962 Moon Speech, in which he three times used the words “conquer” and “conquest.” While Kennedy’s rhetoric was intended to bolster U.S. morale in the space race against the USSR, the view of outer space as a venue for conquest evokes subjugation and exploitation and exemplifies an attitude that has resulted in much destruction on Earth. By definition, conquering involves an assertion of power and mastery, often through violence. Similarly, former President Donald Trump is the most recent American president to use the term “Manifest Destiny” to describe his motives for exploring space, tapping into a philosophy that suggests humanity’s grand purpose is to expand and conquer, regardless of who or what stands in the way.

In a recent white paper, a group comprising subject-matter experts at NASA and other institutions warned of the hazards of invoking colonial language and practice in space exploration. “The language we use around exploration can really lead or detract from who gets involved and why they get involved,” Natalie B. Treviño, one of the paper’s coauthors, told me.

Treviño, who researched decolonial theory and space exploration for her Ph.D. at Western University in Canada, is a member of an equity, diversity, and inclusion working group that makes equity-related recommendations in the planetary science research community. She notes that certain words and phrases can be particularly alienating for Indigenous people. “How is an Indigenous child on a reserve in North America supposed to connect with space exploration if the language is the same language that led to the genocide of his people?”

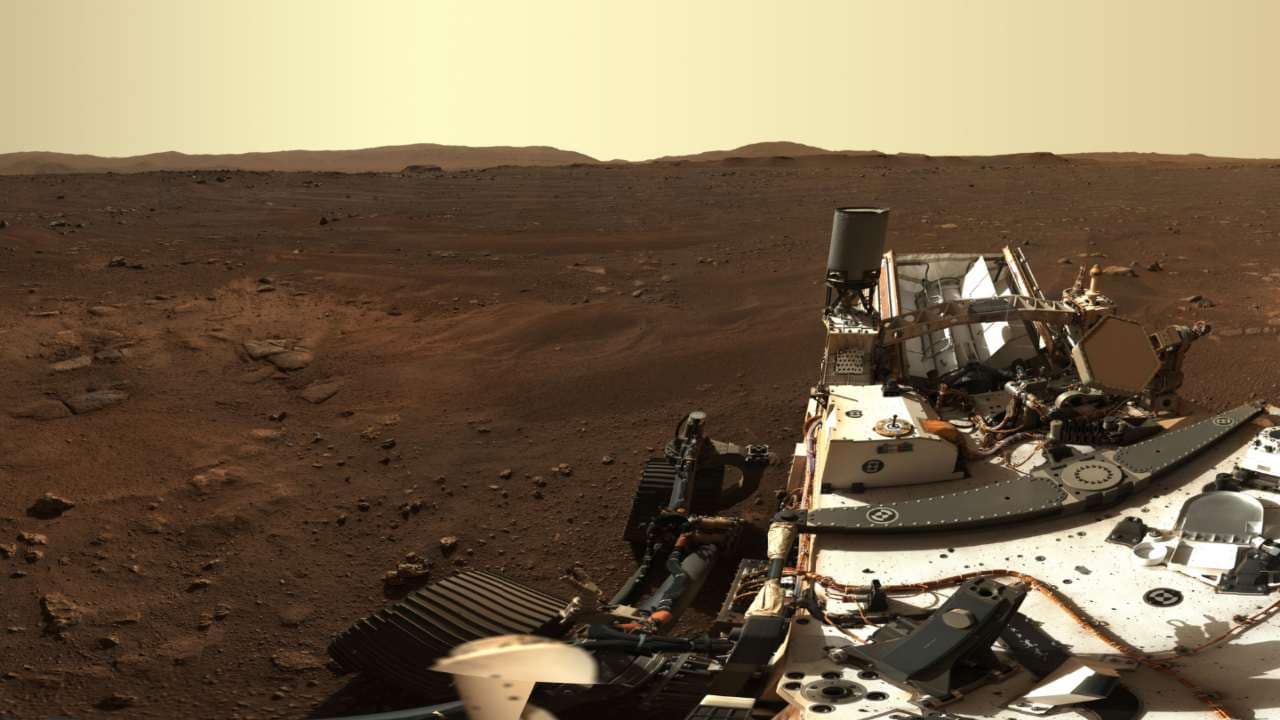

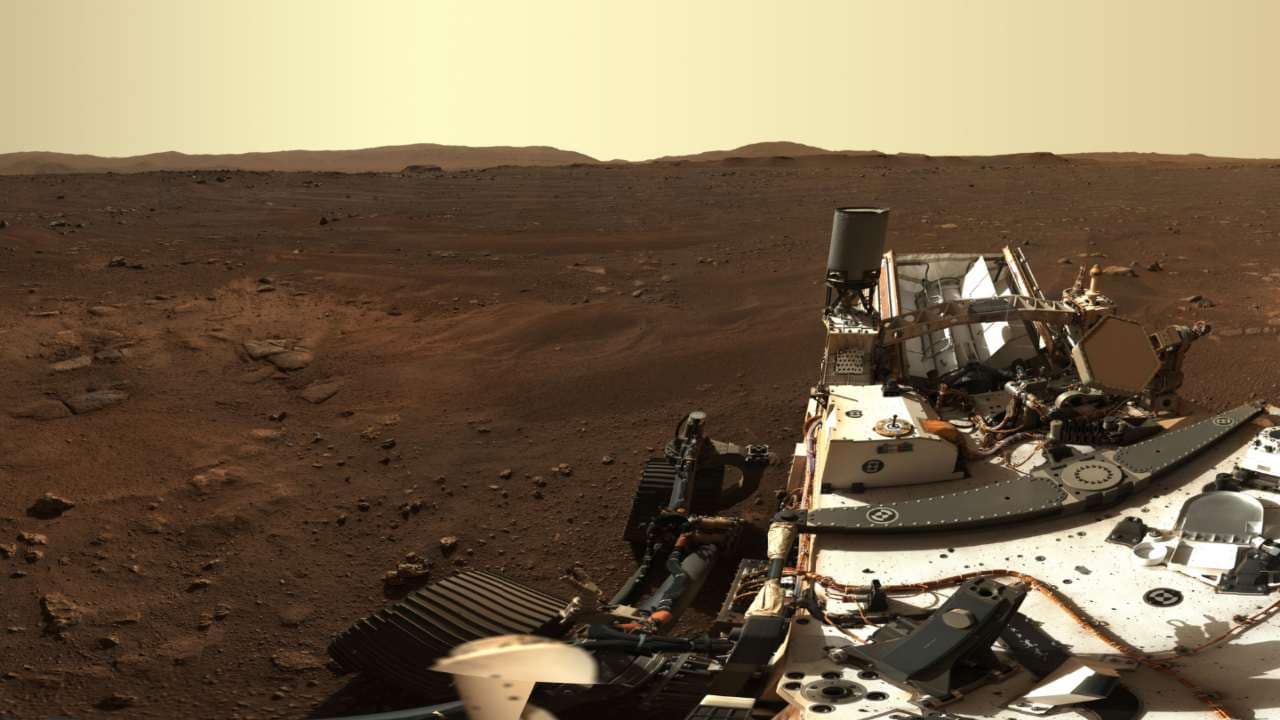

Perseverance rover's MASTCAM-Z has captured its first high-resolution panorama of its landing site in the Jezero Crater on Mars. The image will help the mission team narrow down rocks of interest to return to Earth for study. Image: NASA

In a 2020 perspective for Nature Astronomy, Aparna Venkatesan of the University of San Francisco, also a coauthor of the recent white paper, wrote with colleagues that in the dialects of the Indigenous Lakota and Dakota, the concept of thought being rooted in language, space, and place “is epitomized by the often used phrase mitakuye oyasin, explained by Lakota elders as a philosophy that reminds everyone that we all come from one source and so need to respect each other to maintain wolakota or peace.” It’s difficult, if not impossible, to reconcile the ideas of wolakota and conquest, especially given the increasing weaponization of space.

Treviño argues that the word “frontier,” the guiding metaphor for American space exploration, is also problematic. The crossing of new frontiers — because frontiers always must be pushed or crossed — is inevitably “tied to nationalism, and nationalism is tied to conquest, and conquest is tied to death,” she says. When humans push frontiers, they often do so with the belief that it is their right as individuals or as representatives of a country or state. Throughout history, this sense of entitlement has been taken as license to wipe out Indigenous people and fauna, pollute rivers, and otherwise demonstrate ownership and mastery.

Foundational concepts such as “conquest,” “frontier,” and “Manifest Destiny,” can affect not only how people think about space but also how they act toward it. In their Nature Astronomy paper, Venkatesan and her colleagues argue that in addition to promoting colonialist ideals, such concepts promote space capitalism and a lack of regulation. Potent symbols of this trend are the more than 3,000 operational satellites currently orbiting Earth, many of them privately owned. For people who use the stars to navigate, or who incorporate celestial bodies into cultural, spiritual, and religious practices, this intrusion into the skies threatens to compromise a way of life. And it is a sobering reminder that space and the sky don’t really belong to everyone after all. The lack of protections and regulations for the night sky — as well as monetary incentives for commercial satellites, which make up almost 80 percent of U.S. satellites — make it vulnerable to the highest bidder.

“Treating space as the ‘Wild West’ frontier that requires conquering continues to incentivize claiming by those who are well-resourced,” writes Venkatesan and her colleagues. In fact, the staking of claims in space has already begun, with space tourism predicted to develop into a lucrative industry, and with the U.S. government opening the doors to commercial endeavors such as the mining of asteroids and the colonization of Mars.

While scientists often devote themselves to questions of feasibility, scalability, and affordability, they rarely give as much thought and effort to questions of inclusivity and morality. “In the space community, when ethics or values or planetary protection come up, they’re immediately coded as feminine and they’re immediately coded as not as important,” Treviño told me. For many scientists, she says, “thinking about ethics isn’t nearly as important as building the rovers that are going to go to the moon.”

The “act first, ask questions later” approach typifies the mindset that has led some to argue that humans need to colonize space to survive. But attitudes and ethics cannot be applied retroactively. Science might get people to Mars, but without ethics, what are the chances of survival?

In Kennedy’s words, space exploration is our species’ most “dangerous and greatest adventure.” It makes sense to address factors that influence human behavior in space — and that will ultimately determine our odds of success there — sooner rather than later. That includes asking everyone, not just NASA or Elon Musk, what we want an interplanetary future of humanity to look like. Would we want futuristic Mars settlements to operate like modern-day Earth towns, or could we do better?

Crafting a code of ethics for space exploration may seem daunting, but our words offer a potential starting point. Space is one of few places humans have gone that thus far remains peaceful. Why, then, use the language of war, imperialism, or colonialism to describe human actions there? Eliminating the language of genocide and subordination from the space discourse is one easy step anyone can take to encourage the great leaps for humankind that we dream of for the future, on Earth and beyond.

Joelle Renstrom is a science writer who focuses on robots, AI, and space exploration. She teaches at Boston University.

This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article.

Paul Apostolidis – LSE Government

Paul Apostolidis – LSE Government