BET HE WOULD BE ON THE FLOTILLA

Albert Einstein, Palestine and Israel Today

Albert Einstein is one of the most famous and influential scientists of all time. His theories and equations regarding time, energy, space, and gravity are foundational to modern physics.

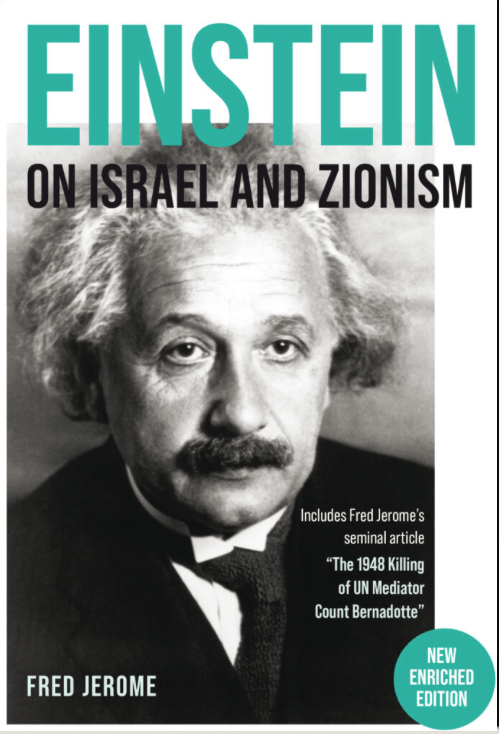

Less well known, Einstein was a very political figure, with strong beliefs and a willingness to act on them. The book “Einstein on Israel and Zionism” documents what he thought about Palestine, discrimination against Jews in Europe, and what he would probably say about Israel were he alive today.

Background on Albert Einstein

Born in Germany in 1879. Albert Einstein was a precocious student, mastering mathematics and appreciating philosophy, especially the philosophy of Thomas Kant, at a young age. With his father’s permission, he left Germany at age 15 to avoid being drafted into the army. He became a Swiss citizen and completed his education in Switzerland. Einstein graduated from the University of Zurich and began his landmark research and writing. In 1905, he published four groundbreaking papers, and his fame spread rapidly. In 1914, Einstein was enticed by Max Planck and other German scientists to return to Germany shortly before World War 1 began. Antisemitism against Jews in Germany, especially against Jews migrating from Eastern Europe, was widespread. Einstein said, “When I came to Germany (in 1914) … I discovered for the first time that I was a Jew.”

Einstein opposed the intense nationalism of World War I. While many prominent Germans signed a “Manifesto of the Ninety-Three” which justified Germany’s belligerence, Einstein was one of the few who signed a contrary “Manifesto to Europeans” which said, “The struggle raging today will likely produce no victor; it will leave probably only the vanquished … the time has come where Europe must act as one in order to protect her soil, her inhabitants, and her culture.”

In 1933, as Adolph Hitler came to power in Germany, Einstein immigrated to the U.S. at the invitation of Princeton University. He became a U.S. citizen in 1940.

Einstein fought against anti-Semitism.

After WW1, the economy in Germany was bleak, and there was a sharp rise in anti-Semitic attacks. Einstein wrote, “East European Jews are made the scapegoats for the malaise in present-day German economic life, which in reality is a painful after-effect of the war.”

Einstein developed his sense of being Jewish and his wish to see a “safe haven” for discriminated Jews. He supported the campaign for migration to Palestine. In 1921, he toured the U.S. with Chaim Weizman, president of the World Zionist Organization. Their goal was to raise funds for Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Einstein wrote to a friend, describing the tour’s success. He was especially impressed with the support and funds raised from Jewish American doctors. However, in an early forewarning, Einstein also noted that “a high-tensioned Jewish nationalism shows itself that threatens to degenerate into intolerance and bigotry; but hopefully this is only an infantile disorder.”

Einstein was a “cultural” Zionist.

Einstein believed that Palestine could be a “safe haven and homeland” for Jews if they lived in peace and equality with the indigenous Arabs. This was termed a “cultural zionist”. Like some other prominent Jews, such as philosopher Martin Buber and the head of Hebrew University, Judah Magnes, Einstein wanted an independent and sovereign Palestine to be a binational state, NOT a “Jewish state.”. As the German translator of Einstein’s documents, Michael Schiffmann, explained, “This volume clearly demonstrates that Einstein, right from the beginning, championed what was in accord with elementary morality: The creation of a ‘Jewish home’ in Palestine would turn into a crime if it resulted in the dispossession of the native Arab population.” Another translator explained, “Professor Einstein’s nationalism has no room for any kind of aggressiveness or chauvinism.” “For him, the domination of Jew over Arab in Palestine, or the perpetuation of a state of mutual hostility between the two peoples, would mean the failure of Zionism.”

In 1929, in the wake of Arab- Jewish conflicts in Palestine, Einstein wrote, “The first and most important necessity is the creation of a modus vivendi with the Arab people. … We Jews must show above all that our own history of suffering has given us sufficient understanding and psychological insight to know how to cope with this problem …. Let us therefore above all, be on our guard against blind chauvinism of any kind, and let us not imagine that reason and common sense can be replaced by British bayonets…. We must not forget for a single moment that our national task is, in its essence, a supra-national matter, and that the strength of our whole movement rests in its moral justification, with which it must stand or fall.”

Einstein advocated “the creation of an Arab-Jewish community that brings those two tribally related peoples to each other while excluding nationalist fanatics.”

He believed, “All Jewish children (in Palestine) should be obligated to learn Arabic.”

Balfour Declaration and differing zionist goals

The editor of this book, journalist and Columbia University professor Fred Jerome, provides the historic context. He explains how Herzl proposed to the British that European Jewish immigration to Palestine “would form part of the rampart against Asia, serving as an outpost of civilization against barbarism.” Jerome explains, “Supporting Zionism and a Jewish settlement in the Middle East clearly had a direct value to the British and other colonial powers as they sought to extend their grasp further into Africa and Asia.”

The 1917 Balfour Declaration facilitated Jewish migration to the land of Palestine. When conflict with the indigenous population erupted, this was also advantageous because it justified the installation of tens of thousands of British troops in a key region close to Egypt and the vital Suez Canal.

Einstein believed that Britain (which took over management of Palestine after WW1) was intentionally promoting division between Arabs and immigrating Jews. He believed they were practicing a divide-and-conquer policy, as done in other British colonies, to prevent the locals from uniting, assuming control of the land, and expelling the colonial power.

In 1948, Einstein wrote, “When a real and final catastrophe should befall us in Palestine, the first responsible for it would be the British, and the second responsible for it the terrorist organizations built up from our own ranks.”

Einstein urged equality and a binational state.

Einstein was remarkably clear and consistent. In 1946, he wrote, “I am firmly convinced that a rigid demand for a ‘Jewish state’ will have only undesirable results for us.”

He also said, “Only direct cooperation with the Arabs can create a dignified and safe life. If the Jews don’t comprehend this, the whole Jewish position in the complex of Arab countries will become, step by step, untenable. What saddens me is less the fact that the Jews are not smart enough to understand this, but rather that they are not just enough to want it.”

Einstein was egalitarian and anti-fascist. He urged to “institute complete equality for the Arab citizens living in our midst… The attitude we adopt toward the Arab minority will provide the real test of our moral standards as a people.” ”

The famous American journalist Izzy Stone (I.F. Stone) was also a progressive Jew. He wrote, “To have the greatest Jewish figure of the period oppose a Jewish state as unfair to the Arabs was a very noble thing.” ”

Einstein condemned Jewish nationalism and terrorism.

Einstein was clear and consistent in condemning Zionist ultra-nationalism and terrorism. Einstein wrote, “I have come across Zionism only after my move to Berlin, in the year 1914 at the age of 35……The time has come to take care that this movement avoids the danger of degenerating into blind nationalism.” ”

In 1948, Einstein and twenty-eight other prominent American Jews sent a 750-word letter to the New York Times. In the letter, they assailed the upcoming visit of Menachim Begin, who was formerly the head of the terrorist Irgun and current leader of Israel’s new Herut (Freedom) party. This party is the predecessor of today’s Likud Party, led by Benjamin Netanyahu. The letter compares Begin and his organization to Nazi and Fascist parties. The massacre of about 200 Palestinians in the village of Deir Yassein, carried out by Begin and his organization, is described. The letter also says, “Within the Jewish community, they have preached an admixture of ultra-nationalism, religious mysticism, and racial superiority.”

At different times over this period, Einstein expressed his concern that Judaism would be damaged by ultra-nationalism (political Zionism). He said, “I am afraid of the inner damage Judaism will sustain – especially from the development of a narrow nationalism within our own ranks.”

He also said, “I think that nationalism is always a bad thing, even if it is Jews among whom it is raging.”

After Israel replaced Palestine

After Israel declared its “independence” in 1948, Einstein recognized that his struggle to create a binational state rather than a “Jewish” state was lost. He did not change his views that this was negative, but recognized the new reality.

Due to his international prominence, Einstein was invited to serve as the figurehead President of Israel after the death of Chaim Weizmann. He declined, saying privately that he would have had to tell them things they would not like to hear.

Einstein supported the non-aligned movement and leaders like Nehru of India, Sukarno of Indonesia, and Nasser of Egypt. When a famous Egyptian journalist visited the U.S. and requested an interview with Einstein, he used the occasion to reach out to the Egyptian president discreetly. He hoped to serve as a catalyst for rapprochement between Israel and the Arab states. Unknown to Einstein, the Israelis were doing just the opposite: they were planting bombs and carrying out sabotage actions against U.S. and British targets in a false flag effort, trying to sow chaos and implicate the Egyptians. Instead of seeking compromise and reconciliation, the Israeli leadership was exacerbating conflict with Egypt and other Arab states.

In a January 1955 letter, Einstein expressed his wishes regarding Israel: “First: Neutrality with regard to the international East-West antagonism…. Second, and most importantly: We must incessantly strive to treat the citizens of Arab descent living in our midst as our equals in every respect, and we must develop the necessary understanding for the difficulties of their situation, naturally accompanying it.” ”

Einstein was an internationalist and pacifist.

Einstein opposed McCarthyism and the suppression of free speech that was pervasive in the early 1950s. He was a good friend to the legendary African American Paul Robeson when Robeson was being attacked by the right as well as the FBI. Einstein supported Progressive Party candidate Henry Wallace in the 1948 presidential race. He was especially concerned with the rise of the Cold War. He opposed the nuclear arms race and the establishment of NATO.

Based on Einstein’s biography and political views, it is clear that he would be horrified and strongly oppose Israel’s genocidal actions and apartheid against Palestinians. He would be outraged at the suppression of free speech and blind support for Israel as it practices fascism based on an “admixture of ultra-nationalism, religious mysticism, and racial superiority.” He would also be very sad.