JULIE HOLLAR ON 1/7/20

VIDEO

02:58

Sixth 2020 Democratic Debate Highlights

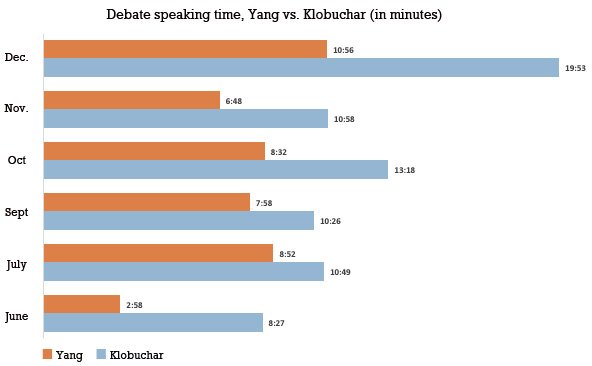

The Democratic primary field may be narrowing, but Andrew Yang still can't get the media's attention. According to The New York Times, which breaks down the debates by speaking minutes, Yang, polling at fifth of the seven participating candidates, with an average of 3.5 percent, came in last in the December debate at 10 minutes, 56 seconds; that's nearly a minute less than Tom Steyer (polling at 1.5 percent) and far below centrism poster child Amy Klobuchar, who is neck-and-neck with Yang in polls but clocked a whopping 19 minutes and 53 seconds.

It's part of a pattern for Yang. In the November debate, he also came in dead last on speaking minutes, at 6:48, despite polling higher than fellow debaters Klobuchar, Steyer, Tulsi Gabbard and Cory Booker. He also had the fewest minutes in the September and June debates. Business Insider found that Yang has consistently received less speaking time at the debates than one would expect, given his polling numbers.

By FAIR's count, he's been given 37 prompts across the six debates; Klobuchar—who has consistently polled below Yang for months, though her numbers have risen slightly to match his in recent weeks—has gotten 54. Booker and Beto O'Rourke, who didn't even appear in all six debates and have polled at or below Yang's levels since September, received 43 and 36, respectively.

An analysis by the national media watch group FAIR shows that Andrew Yang consistently got less speaking time in debates than fellow candidate Amy Klobuchar.COURTESY OF FAIR.ORG

An analysis by the national media watch group FAIR shows that Andrew Yang consistently got less speaking time in debates than fellow candidate Amy Klobuchar.COURTESY OF FAIR.ORGYang's campaign focus is on a universal basic income of $1,000 a month, and his background is in business; perhaps as a result, a disproportionate number (10) of the questions he's been asked relate to economic issues. The other topic he's gotten a disproportionate number of questions on? China. With three China-related questions aimed at (U.S.-born) Yang, only Pete Buttigieg (with 63 total prompts) has gotten to speak about the subject as much.

But given the lack of overall questions directed to him, Yang has been largely missing from the conversation on health care, one of the issues given the most attention in the debates; he has been asked only three of the 127 questions on the topic. (More questions about his position on health care would be quite useful; Yang says his plan embraces the "spirit of Medicare for All," though his plan does not involve everyone getting Medicare, or even being offered a public option. Of 71 questions related to governance (things like impeachment, bipartisanship and money in politics), Yang has gotten two. Guns have accounted for 39 of the debate questions; none went to Yang.

As others have documented, Yang's media woes extend beyond the debates. Yang has been repeatedly left out of MSNBC and CNN on-screen graphics showing the Democratic candidate lineup; MSNBC once even misidentified him as "John Yang." Yang briefly boycotted MSNBC, demanding an on-air apology for its sleights. (He ended his boycott, without the on-air apology, on Chris Hayes' show in December.)

In the last six months, Yang has been mentioned 98 times on ABC, CBS, NBC and CNN; Klobuchar has gotten 149 mentions. (MSNBC was omitted from FAIR's search because of Yang's one-month boycott.)

It's possible that some of the discrepancy between Klobuchar and Yang's speaking time in the debates could in part be due to how often other candidates referenced them (which, by debate rules, generally gives the named party the right to respond), or how aggressively they vie for the moderators' attention, or push past allotted time limits. (For the record, a review of the December debate didn't turn up instances where Klobuchar was given a chance to respond to being invoked by another candidate, though several prompts noted that she had her hand up.) But it's the moderators' job to provide a fair playing field—which they are obviously failing at here.

CNN's Chris Cillizza acknowledged that Yang "should be getting more attention" from media, but made sure to get in some digs at Yang's supporters who had called out that lack of coverage: "What it's not is some sort of widespread media conspiracy out to get Yang. (Sorry Yang Gang!)"

Cillizza blamed Yang's being an "outsider" (which meant that "at the start of the race no one—including reporters—had any sense of who he was"), that his ideas are "radically different...and different poses challenges to a media used to covering a political race via a certain set of established guidelines," and that Yang is like erstwhile Republican candidate Ron Paul, who "could never grow his support beyond that dedicated core."

Cillizza's arguments seem to depict journalists as quite an intellectually challenged crew. In reality, it's not that they can't work to get a sense of a new candidate or to cover "radical" political ideas; it's that the news organizations they work for give them no incentive to—no conspiracy necessary, just an unhealthy bias toward the political establishment. Witness: A search of all CNN transcripts after Cillizza's September 4 mea culpa found not a single instance of Cillizza mentioning Yang's name on the air.

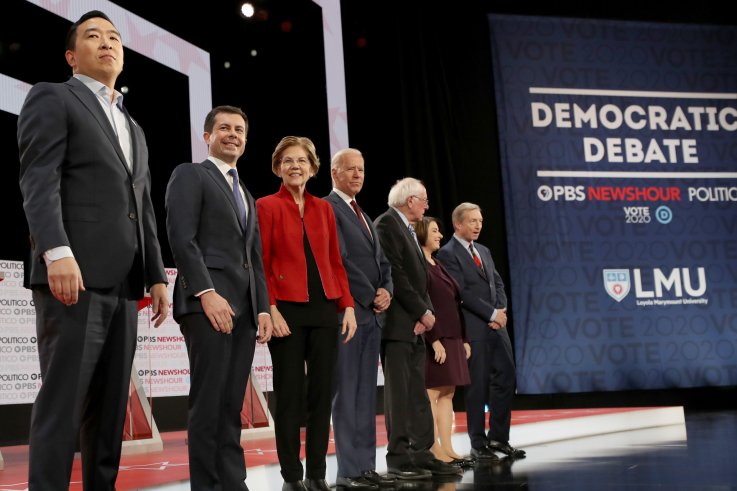

Democratic presidential candidates away the start of the

Democratic presidential primary debate on December 19,

2019, in Los Angeles.MARIO TAMA/GETTY

Echoing Cillizza's third point, New York magazine's Ed Kilgore suggested journalists may be ignoring Yang because he has "no plausible path to the Democratic nomination," given that his support mainly lies among millennials and Asian Americans, and that if he had a breakout debate performance "his media coverage will skyrocket." How Yang might be expected to have a breakout debate when the moderators keep him on the sidelines isn't clear.

But the idea of a candidate having "no plausible path" to victory is a self-fulfilling prophecy: Journalists decide a candidate can't win, so they don't give the candidate coverage, which means the candidate can't reach voters, influence the political discussion and rise in the polls. The whole point of the primaries is to let voters get to know the candidates and decide for themselves who is electable—the last thing people need is journalists narrowing the field for them.

Yang himself suggested recently that his race may have something to do with the lack of coverage, "in the sense that my candidacy seems very new and different to various media organizations." It's a perspective shared by author Marie Myung-Ok Lee, who wrote in a Los Angeles Times op-ed:

"There is no way to prove these omissions are related to Yang's being Asian, but it's impossible to miss the similarities with the micro (and macro) aggressions people in the Asian-American community experience daily."

Media observers have lamented the decreasing diversity of the Democratic debates, as Yang was the only candidate of color in the December debate. But their treatment of Yang, both in the debates and in the coverage, indicates little real interest in confronting media's role in that.

Julie Hollar is senior analyst for FAIR's Election Focus 2020 project. She was managing editor of FAIR's magazine, Extra!, from 2008 to 2014.

This piece originally appeared on FAIR.org. Republished with permission.

The views expressed in this article are the writer's own.

Echoing Cillizza's third point, New York magazine's Ed Kilgore suggested journalists may be ignoring Yang because he has "no plausible path to the Democratic nomination," given that his support mainly lies among millennials and Asian Americans, and that if he had a breakout debate performance "his media coverage will skyrocket." How Yang might be expected to have a breakout debate when the moderators keep him on the sidelines isn't clear.

But the idea of a candidate having "no plausible path" to victory is a self-fulfilling prophecy: Journalists decide a candidate can't win, so they don't give the candidate coverage, which means the candidate can't reach voters, influence the political discussion and rise in the polls. The whole point of the primaries is to let voters get to know the candidates and decide for themselves who is electable—the last thing people need is journalists narrowing the field for them.

Yang himself suggested recently that his race may have something to do with the lack of coverage, "in the sense that my candidacy seems very new and different to various media organizations." It's a perspective shared by author Marie Myung-Ok Lee, who wrote in a Los Angeles Times op-ed:

"There is no way to prove these omissions are related to Yang's being Asian, but it's impossible to miss the similarities with the micro (and macro) aggressions people in the Asian-American community experience daily."

Media observers have lamented the decreasing diversity of the Democratic debates, as Yang was the only candidate of color in the December debate. But their treatment of Yang, both in the debates and in the coverage, indicates little real interest in confronting media's role in that.

Julie Hollar is senior analyst for FAIR's Election Focus 2020 project. She was managing editor of FAIR's magazine, Extra!, from 2008 to 2014.

This piece originally appeared on FAIR.org. Republished with permission.

The views expressed in this article are the writer's own.

No comments:

Post a Comment