PUBLISHED SAT, FEB 8 2020

KEY POINTS

The $2.5 trillion fashion industry is one of the biggest polluters and the second-biggest consumer of water.

The major issue is that most of the fabrics in cheap garments are synthetics and polyesters, which are derived from oil and petroleum production.

Unlike wool or cotton, synthetic particles don’t biodegrade. So when clothes are dumped into a landfill, toxic synthetic fibers pollute water sources.

Protesters display banners during a fashion show in a polluted river basin planted mostly with rice in Rancaekek district near Citarum river located in western Java island as part of a campaign by environmental organization Greenpeace for top international fashion brands to remove toxic chemicals from their supply chains in Indonesia and address water pollution.

Romeo Gacad | Getty Images

Hannah George grew up shopping at the malls in Ithaca, New York, where she stocked up on the latest affordable trends at retailers such as H&M and Forever 21.

The 25-year-old abruptly stopped, however, when she went to college and learned about fashion industry pollution, a major driver of climate change. She shifted toward buying used clothes at the local thrift shops, actively avoided synthetic, petroleum-based fabrics and began investing in clothes made to last.

“I realized how I was supporting the industry with my dollars,” George said. “It was a shift for me. I looked at what my philosophy for clothing should be — a long-term part of my life, not just something for the night out.”

Growing calls for sustainable clothing that’s less harmful to the environment could be a catalyst for change in the fashion industry. Sixty-two percent of Gen Z consumers, those who were born after 1995, prefer to buy from sustainable brands, according to one recent survey.

Consumer pressure over the industry’s pollution has led companies such as Nike and H&M to announce plans to reduce carbon emissions or use more recycled materials in clothing. Meanwhile, larger retailers are getting into used clothing as the secondhand market booms. Nordstrom last week launched a resale shop, citing consumer demand for more sustainable options.

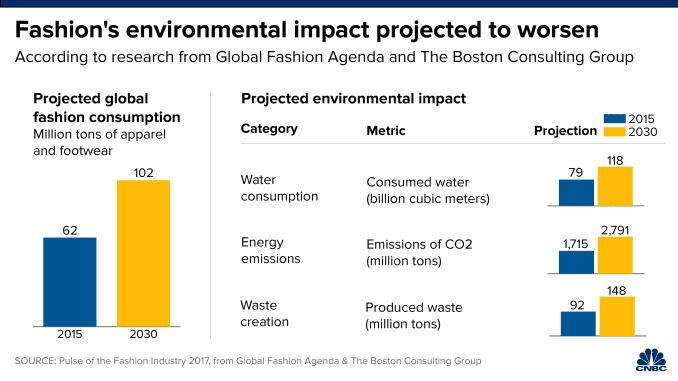

But despite talk of shifting toward more sustainable production, the global fashion industry’s greenhouse gas emissions are on track to surge more than 50% by 2030 as global demand for apparel rises.

“Fashion is on par to become a quarter of the global footprint of carbon. That’s astounding,” said Michael Stanley-Jones, co-secretary of the UN Alliance for Sustainable Fashion. “The industry isn’t headed in the right direction.”

“The urge to sell more and more, produce more and get consumers to buy more is still the DNA of the industry. Clothes have a short life span and end up in a garbage dump,” he added. “That has to change.”

The $2.5 trillion fashion industry comprises roughly 10% of global greenhouse gas emissions — more than all international flights and shipping in total, according to the United Nations Environment Program. It’s also the second-biggest consumer of water globally, enough to meet the needs of 5 million people every year.

Fast fashion is a major culprit. Large, low-cost global clothing brands are consistently ramping up production and inventory turnover to offer consumers new designs and collections every few weeks, rather than every season.

Extinction Rebellion activists demonstrate outside the Foreign Office ahead of Victoria Beckham’s show at the London Fashion Week on 15 September, 2019 in London, England.

Wiktor Szymanowicz | Getty Images

As a result, consumers regularly shop for new looks and treat the cheap garments as essentially disposable, throwing them out after no more than 10 wears.

Between 2000 and 2015, the fashion industry doubled production. The average shopper bought 60% more clothing, too, but kept each product for about half as long, according to research from consulting firm McKinsey.

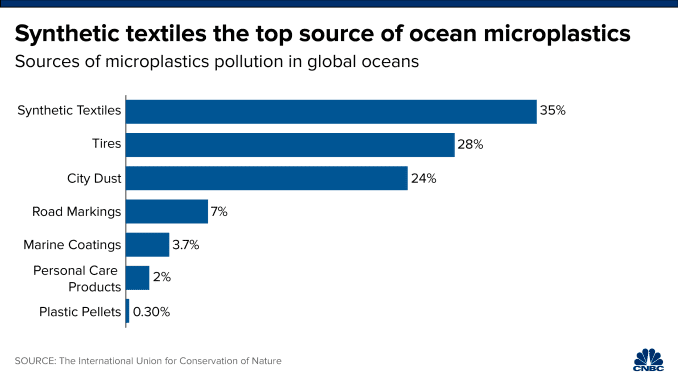

The major issue is that most of the fibers in these cheap garments are synthetics and polyesters, which are derived from oil and petroleum production.

Unlike wool or cotton, synthetic particles don’t biodegrade. So when clothes are dumped into a landfill, toxic synthetic fibers pollute water sources.

When the clothing is washed, microplastic fibers will shed off and inundate the water supply and food chain.

The chemicals used in producing and dying these fabrics harm the environment, too. In fact, the problem is so pervasive that the Environmental Protection Agency considers many textile manufacturing facilities to be hazardous waste facilities.

“Consumers might think they are getting something for nearly nothing — clothing designed to become garbage — but they should ask, what are the real costs of the product?” said Stanley-Jones. “The real cost of production of these products involves pollution that affects your health and costs the national health system.”

The production of synthetic textiles is accelerating as the demand for cheap clothes continues to rise. And in turn, the amount of textiles that are filling landfills is skyrocketing.

In the U.S., people on average produce about 75 pounds of textile waste each year, according to EPA data.

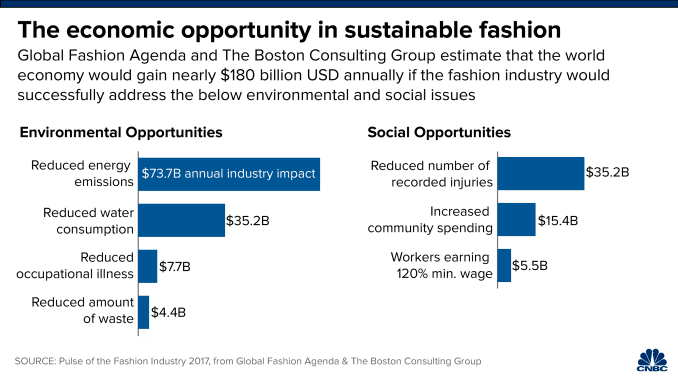

Garment waste is not only a sustainability issue but an economic problem, too. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation estimates that about $500 billion is lost each year as a result of clothing being thrown out instead of being reused or recycled.

A push for sustainable clothing

“2019 was a year of waking up to the urgency of the sustainability issue, and 2020 is a pivotal year for those who can demonstrate impact, and those who will be left behind,” said John Thorbeck, chairman of consultancy Chainge Capital and a former industry executive.

But it’s a complicated shift, considering that many customers also expect a level of speed and price for clothing in line with the fast-fashion companies that are making products for impact, not longevity.

In the midst of public backlash against cheap, throwaway products, many retailers say they are addressing sustainability. Some companies have started addressing textile waste and synthetic fabrics that don’t biodegrade and looking at ways of sustainably sourcing fabrics and recovering or recycling clothing.

For instance, fast-fashion brands H&M and Zara, which sell low-priced items in large amounts, have both raced to make a sustainability remittance.

H&M has a garment collection initiative that allows customers to drop off used clothing in its stores for reuse and recycling. About 57% of its materials are currently either recycled or sourced in a more sustainable way, an increase from 35% in one year, a company spokesperson told CNBC. The company’s goal is to have all materials recycled or sourced sustainably by 2030.

Inditex, the retail giant that owns Zara, announced that all of its clothes will be organic, sustainable or recycled by 2025, and that renewable sources will power 80% of energy used by the corporation’s distribution centers, stores and offices.

However, these sustainability initiatives have been met with some skepticism, with critics pointing out that the business model of fast fashion and sustainability are simply incompatible.

The argument is that when a business is built on such a fast turnover of styles, the production of those garments is extremely energy intensive, regardless of whether the companies have more environmentally friendly stores or materials.

For their part, consumers can help to lower their clothing footprint by reading clothing labels and researching how the products were made before purchasing them, as well as buying used clothing on shopping apps or in thrift stores.

“The consumer is not just looking for a perfect blouse but a company that is actually contributing to a better world. It’s part of a brand identity and a story they will tell,” Thorbeck said.

— Charts by CNBC’s Nate Rattner

No comments:

Post a Comment