THE RESCUE OF THE FABULOUS LOST LIBRARY OF DEIR AL-SURIAN

By Philip McCouat

THE HIDDEN BENEFITS OF BEING LOST

On the morning of 29 December 1935, the French writer and pilot Antoine de Saint-Exupéry took off from Paris en route to Cochin-China, as a participant in the long-distance Paris-to-Saigon air race. That night, flying towards Casablanca across the dark vastness of the Sahara Desert, with no landmarks, he got lost and crashed. Although the crash site was not far from the isolated ancient monastery settlement of Wadi el-Natrun, it was four days before the parched and ravenous St Exupéry and his co-pilot, exhausted and delusional, would finally be rescued by Bedouin tribesmen [1].

For Saint-Exupéry, it must have seemed like an all-time low – out of the air race, physically and mentally depleted, and with his plane a wreck. But at least he was alive, and the incident would later pay substantial dividends – it would form the basis of his famous book Wind Sand and Stars, and inspire his classic The Little Prince, later voted as the best novel of the 20th century in France. In retrospect, getting lost was probably the best thing that could have happened to him.

More articles on Egypt

Egyptian blue: the colour of technologyEgyptian Blue: the Colour of Technology

Elsheimer’s Elsheimer’s Flight into Egypt: how it changed the boundaries between art, religion and science

The Life and Death of Mummy Brown

Lost Masterpieces of Egyptian Art

Fig 1: Saint-Exupéry standing at the wreck of Caudron C630 Simoun (Bureau d’Archives des Accidents d’Avions)

Strangely enough, in a quite different context, Wadi el-Natrun itself – and, in particular, its legendary library – would also come to experience the benefits of getting lost. In this case, those benefits would turn out to be virtually priceless. To understand why, we have to backtrack, quite a few millennia.

AN ANCIENT EGYPTIAN PASTNowadays, Wadi el-Natrun has been nominated for status as a World Heritage site [2] and is quite easily accessible – you will eventually come upon it if you travel from Cairo, into the great Western Desert, and head towards the Mediterranean seaport of Alexandria.

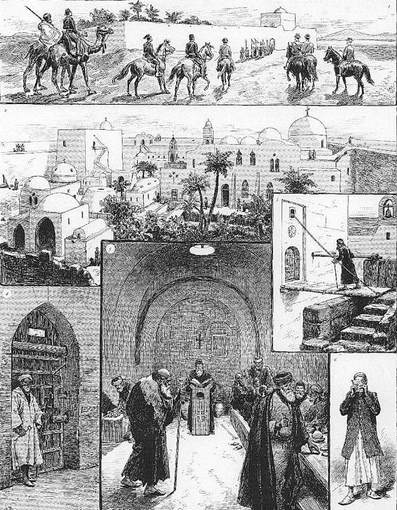

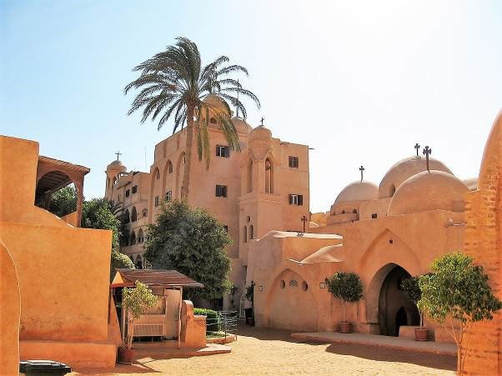

Fig 2: Approaching the Syrian Monastery at Wadi el-Natrun

It’s best known now as a destination for travellers wishing to see the four stunning Coptic Christian monasteries, the only survivors of dozens that were built as part of a Christian settlement at the Wadi dating back to the 4th century -- St Macarius, St Pshoi, the Monastery of the Romans and the Monastery of the Syrians [3].

Fig 3: Inside the Syrian Monastery at Wadi el-Natrun

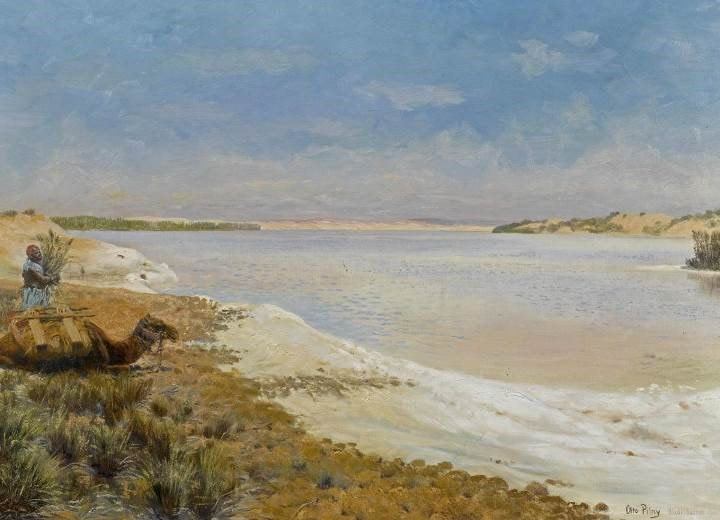

As old as these buildings are, however, the human history of the Wadi goes back even further, in fact over 4,000 years, to the ancient Egyptians. Back then, the Wadi was one of the principal sources of “natron”, the salt which gives the Wadi its name [4]. This natron occurs in solution in a number of seasonal alkaline lakes dotted round the surrounding desert, fed from an underground water table that stretches from the Nile Delta, where the Nile reaches the Mediterranean. These lakes dry out during summer, leaving white evaporitic deposits of natron forming a crust around their edges and in deposits on their bottom [5].

Fig 4: Otto Pilny, At the Wadi Natron Salt Lake (1901), showing evaporative deposits

For the ancient Egyptians, and later the Romans, natron was a precious commodity. It was used to make glass and ceramics, as a soldering agent, medicines, soap and cleaning, toothpaste, mouthwash and food preservative. In addition, as we have discussed elsewhere, the Egyptians used natron as an ingredient in the creation of a blue pigment that was used extensively in Egyptian art (see our article on Egyptian Blue). Even more importantly, natron’s most prominent use was in the process of mummification, a central aspect of Egyptian religious practice, as detailed in our article on Mummy Brown. This central role in both business and cultural life led to the Wadi being known to the Egyptians as the “Field of Salt” and becoming part of a major trade route [6].

No comments:

Post a Comment