What Would A Green New Deal Look Like In Aotearoa?

Jess Berentson-Shaw

Transitional Livelihoods

And what are the preconditions for achieving it?

Top-down solution building is the work of yesterday, not the work for today, or the future. A people-centred Green New Deal could catalyse a system-level transition to a sustainable and universally thriving future for Aotearoa. What is required to see this vision become a reality?

Covid-19 has shown us that the vast majority of people can and do act together out of connection to something greater than our individual selves in times of crisis. People across New Zealand rolled up their sleeves and came together to ensure people in our communities have what we need to get through this together. While people in politics played an important guiding role in supporting the community in this work, the ongoing crises of climate change and ecosystem destruction haven’t had the benefit of the same brave and clear political leadership (yet).

So it is us, the wider community, who are going to have to pave the way to getting through together. Activating a citizen led process requires a clear vision and a roadmap for how people can make a transition to a better relationship with the environment. A vision builds people’s hope about the better life they will experience, and a roadmap gives them the practical achievable steps they and their families, businesses and communities can take to achieve it.

The earth’s ecosystems will not support us if we keep living as we do

As countries have developed and industrialised, our collective activities, (shaped and encouraged by people and industries that reap unfathomable financial benefits), have wrecked the ecosystems that we are part of and that support our health. A heat-trapping blanket of rampant carbon has warmed and acidified the oceans, as global temperatures have risen, our weather patterns become extreme and damaging. Vast deforestation and intensive monocultural farming, threatens our oxygen makers, our pollinators, our food growing systems, and our physical and mental well being.

This way of development has extracted too much from our life-sustaining ecosystems, while extracting from our communities to do so. People on low incomes, indigenous people, women, people of colour, and those with disabilities have been exploited by people profiting from industries interested only in financial return for their shareholders. These marginalised groups have been injured by industrial processes or in the process of protecting their lands and communities from confiscation, theft and resource extraction. Most of all, they have been shut out of the benefits of this industrial economy through systems of governing and policy making that orientate to the most visible and powerful.

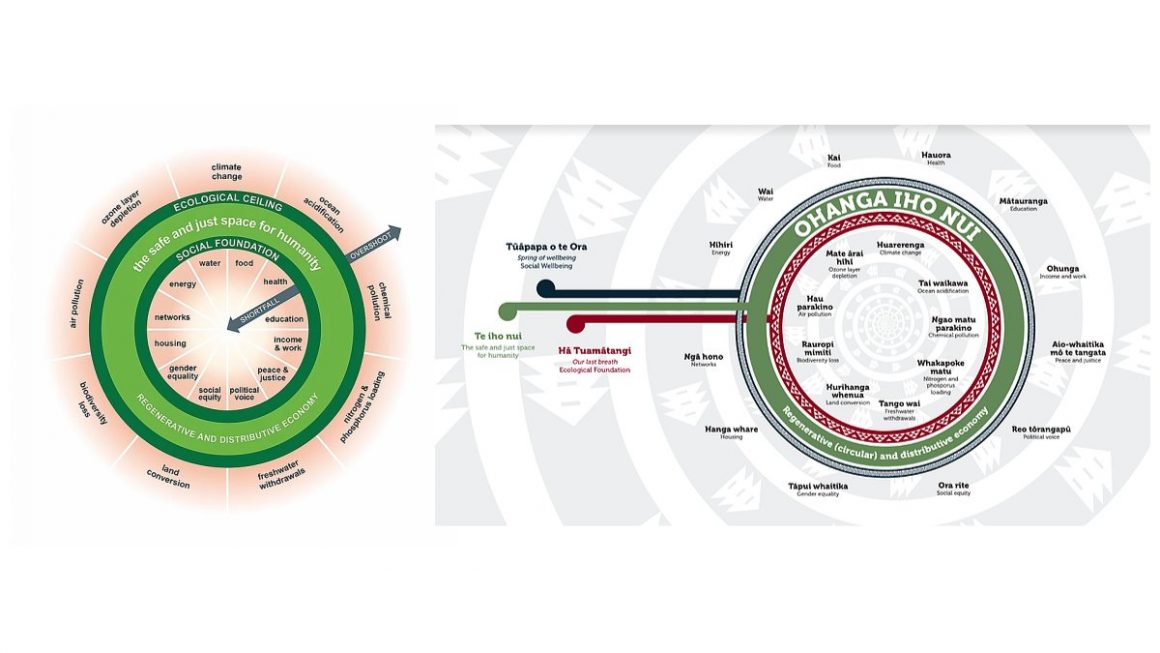

‘Takarangi’ – A Māori take on the Doughnut economy concept – a collaboration between Teina Boasa-Dean, Juhi Shareef,Tineke Tatt and Jennifer McIver.

This systematic destruction of the planet and exploitation of the vulnerable has been primarily driven by a focus on the growth of wealth above all else. However, there are alternative approaches. Kate Raworth in her book Doughnut Economics has called for a refocus towards “meeting the needs of all within the means of the planet” through economies that “make us thrive, whether or not they grow.” This approach reflects indigenous knowledge and economic systems that predate our current extractive approach.

Psychologists tell us that our minds tend to slide away from these realities to minimise their impacts on us, meaning that we tend to find it hard to engage in the much needed change. However we also have it in us to respond, to adapt and to act on this urgent threat to our wellbeing. We paddled across the inlet together to deal with COVID-19. Now we must take our waka into the open waters and seek the new future we all need. How do we chart the course?

Policy makers need to refocus (and help to do it)

This systematic destruction of the planet and exploitation of the vulnerable has been primarily driven by a focus on the growth of wealth above all else. However, there are alternative approaches. Kate Raworth in her book Doughnut Economics has called for a refocus towards “meeting the needs of all within the means of the planet” through economies that “make us thrive, whether or not they grow.” This approach reflects indigenous knowledge and economic systems that predate our current extractive approach.

Psychologists tell us that our minds tend to slide away from these realities to minimise their impacts on us, meaning that we tend to find it hard to engage in the much needed change. However we also have it in us to respond, to adapt and to act on this urgent threat to our wellbeing. We paddled across the inlet together to deal with COVID-19. Now we must take our waka into the open waters and seek the new future we all need. How do we chart the course?

Policy makers need to refocus (and help to do it)

Alexandra Ocasia-Cortez on the campaign trail for a Green New deal

Our current systems of economics and policy making, and our ways of living, all need to be reset and policy makers are key to this task. Tinkering around the edges of the current system (for example investing COVID-19 money in building bike paths next to new roads while relying on the low paid labour of Māori and Pacific communities to do so) is not going to solve the climate or environmental crisis.

To achieve a true reset, people in policy making will need to be focussed much further upstream from the problems that we are currently experiencing. A broad and systemic focus on the upstream rules and policies that encourage and enable extractive practices across government, business and society is required. Our tax and financial systems are key – as Jonathan Barrett of VUW has pointed out, with their conservative campaign promises, “Labour and National lock in existing unfairness in New Zealand’s tax system.” However, just as critical are housing, work and labour, transport, health, agriculture, social and economic development and foreign policy.

Policy makers need shared and clearly articulated and bold goals for actively restoring and rebuilding the health of the planet, and the inclusion of all people, they need a mission (or missions even) that they can work in collaboration with business, iwi, community groups to meet.

How the Green New Deal can help chart the course

Our current systems of economics and policy making, and our ways of living, all need to be reset and policy makers are key to this task. Tinkering around the edges of the current system (for example investing COVID-19 money in building bike paths next to new roads while relying on the low paid labour of Māori and Pacific communities to do so) is not going to solve the climate or environmental crisis.

To achieve a true reset, people in policy making will need to be focussed much further upstream from the problems that we are currently experiencing. A broad and systemic focus on the upstream rules and policies that encourage and enable extractive practices across government, business and society is required. Our tax and financial systems are key – as Jonathan Barrett of VUW has pointed out, with their conservative campaign promises, “Labour and National lock in existing unfairness in New Zealand’s tax system.” However, just as critical are housing, work and labour, transport, health, agriculture, social and economic development and foreign policy.

Policy makers need shared and clearly articulated and bold goals for actively restoring and rebuilding the health of the planet, and the inclusion of all people, they need a mission (or missions even) that they can work in collaboration with business, iwi, community groups to meet.

How the Green New Deal can help chart the course

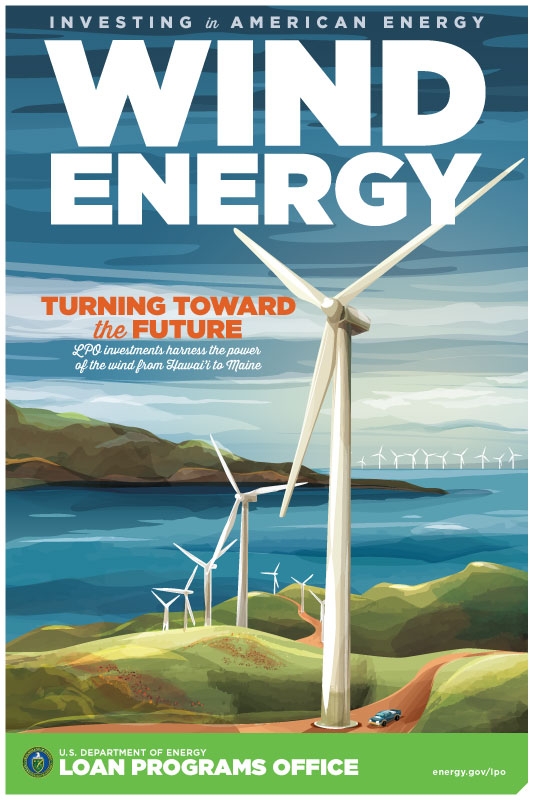

Obama era U.S. Energy Department’s poster series inspired by iconic New Deal-era posters.

This is where the various Green New Deal’s come in. The name harks back to the comprehensive policies instituted by US President Roosevelt in the 1930s to rebuild social and economic systems crippled by the great depression. The Green New Deal proposals are a similarly comprehensive and system level policy intervention aimed at dealing with the upstream causes of the crises of inequality and climate.

The UK Green new deal was born out of a paper written by economists, including Ann Pettifor, in response to the 2008 financial crisis. It recommended a set of joined up policies that aspired to deal with the upstream conditions that shaped the credit crisis, encouraged the release of rampant carbon, and led to high oil prices. What it did was focus squarely on how the rules of our current economic systems shaped climate change, environmental degradation and social inequity. The series of Green New Deal plans now seen across the world, were adapted from that original work and have gained increasing support from the public and across the political spectrum.

This is where the various Green New Deal’s come in. The name harks back to the comprehensive policies instituted by US President Roosevelt in the 1930s to rebuild social and economic systems crippled by the great depression. The Green New Deal proposals are a similarly comprehensive and system level policy intervention aimed at dealing with the upstream causes of the crises of inequality and climate.

The UK Green new deal was born out of a paper written by economists, including Ann Pettifor, in response to the 2008 financial crisis. It recommended a set of joined up policies that aspired to deal with the upstream conditions that shaped the credit crisis, encouraged the release of rampant carbon, and led to high oil prices. What it did was focus squarely on how the rules of our current economic systems shaped climate change, environmental degradation and social inequity. The series of Green New Deal plans now seen across the world, were adapted from that original work and have gained increasing support from the public and across the political spectrum.

A European Green New Deal Vision

Notable examples in play in the real world include the European Commission’s 2019 €1tn ‘European Green Deal’. It aims to transform the 27-country bloc from a high- to a low-carbon economy, without reducing prosperity and while improving people’s quality of life, through cleaner air and water, better health and a thriving natural world. Meanwhile, leading the Asian region, Korea has commited USD$61bn to a Green New Deal by 2025 which they estimate will create 1.9 million new jobs by 2050.

The European Deal has been lauded by Jeffrey Sachs as a global benchmark and a “how-to guide for planning the transformation to a prosperous, socially inclusive, and environmentally sustainable economy.” However, others have advised that close scrutiny to the details is required and that more needs to be done. In all of the current proposals, the risks of industry capture and a focus on ‘green growth’ at the expense of ‘de-growth’ have been raised. This is something that must be actively rejected if the deals are to be truly transformative for people and the planet.

Notable examples in play in the real world include the European Commission’s 2019 €1tn ‘European Green Deal’. It aims to transform the 27-country bloc from a high- to a low-carbon economy, without reducing prosperity and while improving people’s quality of life, through cleaner air and water, better health and a thriving natural world. Meanwhile, leading the Asian region, Korea has commited USD$61bn to a Green New Deal by 2025 which they estimate will create 1.9 million new jobs by 2050.

The European Deal has been lauded by Jeffrey Sachs as a global benchmark and a “how-to guide for planning the transformation to a prosperous, socially inclusive, and environmentally sustainable economy.” However, others have advised that close scrutiny to the details is required and that more needs to be done. In all of the current proposals, the risks of industry capture and a focus on ‘green growth’ at the expense of ‘de-growth’ have been raised. This is something that must be actively rejected if the deals are to be truly transformative for people and the planet.

Where is NZ’s Green New Deal?

Whakaipo planting day. Photo: Kim-Turia

So far no Green New Deal has emerged in New Zealand despite growing calls for this more substantive approach to addressing our current crises. This election we see at best a group of individual policies from the main parties on climate change or conservation that don’t go anywhere near creating a vision of a country that has responded to climate change effectively in the timeframe that is required. There is no clear pathway laid out that articulates the upstream issues or solutions that a Green New Deal covers.

As would be expected after the major job loss of COVID-19, there is huge focus from both Labour and National on “jobs”, and Labour has a nod to “green infrastructure”. Yet these policies are located within status quo thinking about our economic systems and what good jobs are. The Government committed $1.1 Billion in Budget 2020 to restoring our environment through projects anticipated to create nearly 11,000 new jobs in the regions. At the time, this was even labeled a Green New Deal by the Environmental Defence Society. However, such investment falls far short of being a Green New Deal as it fails to address the systemic drivers of the challenges we face.

Absolutely we need jobs. But those jobs need to come from an economy that we have built out of protecting and restoring the environment, from circular systems of production. They also need to come from re-centering the value we place on the work of caring for people, children, people who are ill and disabled, the elderly, both paid and unpaid, as a fundamental activity that must be optimised in order for society to thrive.

Rena oil spill cleanup – Sam Shepherd, NZ Defence Force.

Rena oil spill cleanup – Sam Shepherd, NZ Defence Force.

Good jobs would also ideally be in enterprises owned by the workers themselves through cooperative or community/worker-owned models. This would ensure greater worker control over their labour conditions and transform economic futures of communities. New Zealand lags far behind most developed nations in our adoption of these alternative company models. Our over reliance on unproductive housing to drive our economy, and huge housing costs, don’t enable innovation and creativity (or free up resources to take risks) in business.

Jobs in planting monoculture non-native trees for multinationals exploiting minimum wage labour and precarious employment conditions does not offer economic or environmental transformation for those concerned. This is particularly problematic when such jobs rely heavily on the efforts of Māori and Pacific people, many of whom left school early because the education system excluded them, or worse because of the constraints of poverty. This is not a reset. It is trying to build a new future using the same shonky foundations that led to the problems we currently have.

So far no Green New Deal has emerged in New Zealand despite growing calls for this more substantive approach to addressing our current crises. This election we see at best a group of individual policies from the main parties on climate change or conservation that don’t go anywhere near creating a vision of a country that has responded to climate change effectively in the timeframe that is required. There is no clear pathway laid out that articulates the upstream issues or solutions that a Green New Deal covers.

As would be expected after the major job loss of COVID-19, there is huge focus from both Labour and National on “jobs”, and Labour has a nod to “green infrastructure”. Yet these policies are located within status quo thinking about our economic systems and what good jobs are. The Government committed $1.1 Billion in Budget 2020 to restoring our environment through projects anticipated to create nearly 11,000 new jobs in the regions. At the time, this was even labeled a Green New Deal by the Environmental Defence Society. However, such investment falls far short of being a Green New Deal as it fails to address the systemic drivers of the challenges we face.

Absolutely we need jobs. But those jobs need to come from an economy that we have built out of protecting and restoring the environment, from circular systems of production. They also need to come from re-centering the value we place on the work of caring for people, children, people who are ill and disabled, the elderly, both paid and unpaid, as a fundamental activity that must be optimised in order for society to thrive.

Rena oil spill cleanup – Sam Shepherd, NZ Defence Force.

Rena oil spill cleanup – Sam Shepherd, NZ Defence Force.Good jobs would also ideally be in enterprises owned by the workers themselves through cooperative or community/worker-owned models. This would ensure greater worker control over their labour conditions and transform economic futures of communities. New Zealand lags far behind most developed nations in our adoption of these alternative company models. Our over reliance on unproductive housing to drive our economy, and huge housing costs, don’t enable innovation and creativity (or free up resources to take risks) in business.

Jobs in planting monoculture non-native trees for multinationals exploiting minimum wage labour and precarious employment conditions does not offer economic or environmental transformation for those concerned. This is particularly problematic when such jobs rely heavily on the efforts of Māori and Pacific people, many of whom left school early because the education system excluded them, or worse because of the constraints of poverty. This is not a reset. It is trying to build a new future using the same shonky foundations that led to the problems we currently have.

The pre-conditions for a Green New Deal

Green New Deal activists in Detroit, USA.

So what do people in New Zealand politics need to be able support a New Green Deal approach? They need a roadmap that has been created for them by everyday people who most need change to happen, and they need to feel there is widespread public support for it. That support needs to be built by a range of groups across our communities and society using innovative thinking and tools.

So what do people in New Zealand politics need to be able support a New Green Deal approach? They need a roadmap that has been created for them by everyday people who most need change to happen, and they need to feel there is widespread public support for it. That support needs to be built by a range of groups across our communities and society using innovative thinking and tools.

A new narrative

A good evidence/knowledge based policy package is necessary but not sufficient. Recently Anne Pettifor reflected that the original Green New Deal in the UK struggled to get traction, she put this down to it being written by a group of academics and economists who knew nothing about building a movement behind the ideas. It took the efforts of The Sunrise Movement to take the deal to the political sphere in the US. It takes a diversity of skills and approaches to deliver systemic and structural change.

Providing evidence driven rationales for upstream solutions to address systemic inequities is critical. However, just as important are skills in bringing a diverse range of ordinary people together in agreed and mutually beneficial collective action. Even the best policy solutions in the world need a movement to support them.

It is also important that those in power listen to the wants and needs of communities. Rather than designing policies from the top-down, inviting participation in the process of solving this problem could increase the support and buy-in from the public and ensure the policy works in the local context and for our communities.

Address the “public appetite” problem

Related to the need for building a movement is the no “public appetite” problem. Which is really a public narrative problem. People in politics will often understand at least some of the solutions required to shift a system, but if they see no public appetite for a solution (we could frame this as a lack of leadership), they will fail to act. Any policy package that requires a system reset, also needs effective narratives – a list of ingredients is not the same as selling the cake.

These narratives need to be built on understanding the thinking (mental models) and current narratives that hold a system in place (eg “climate change is too big and scary and governments are useless”). Narratives for change navigate people around this thinking towards deeper more helpful thinking, building support for change. The Green New Deal movement generally does approach narrative in a disciplined and evidence-led way which makes it a powerful vehicle for change worthy of support in New Zealand.

A shift from individual consumer choice to collective action

Related to effective narratives, is a clear focus in public discussion on people acting as citizens. Changing spending habits and acting as conscious consumers matters, but it does little to fundamentally change the rules governing our current extractive economic system.

The more we (those working towards climate action) engage in discussions about individual choice and consumer behaviour in order to act on climate change or environmental degradation, the less likely people are to engage in the collective and civic action needed to achieve systemic change. Engaging people as citizens in a collaborative society lifts people’s gaze to seeing things like the Green New Deal as a critical part of the solution, and will help build the movement required.

Clarity about locating agency and power

Part of the unbalanced focus on individual behaviour results when the source of power for change is not clearly articulated. While collective citizenry is a source of power for the solutions, there are individuals and agencies who actively fight such change. These individuals and the organisations they represent will not voluntarily lead systematic change, not when their bottom lines are going to be affected. They will, the research shows, use a series of tactics to undermine, sow doubt, and actively fight it.

These behaviours need to be named, and the change these ‘blockers’ need to make must be articulated. Tobacco law reform showed us that such people and the values they prioritise, should not be at the decision making table when what is at stake is in the best interest of the public.

Philanthropy gets political

Many people with money and power(including those invested in the fossil fuel industry) are working incredibly hard to hold the status quo in place. Thus, money and power is also needed to help Green New Deal movements grow. Philanthropy is where the money mostly (but not exclusively) is to be found. In New Zealand, Philanthropy has tended to fund bricks and mortar (downstream solutions). It’s a small country and wealthy New Zealanders tend to see funding political movements as risky.

However, people in philanthropy need to recognise how money, lobbying and formal power works against the changes they want to see in the world. Working upstream in philanthropy means using money and power in support of grassroots and political movements for system change.

Embracing Te Tiriti o Waitangi

I speak here as a Pākehā woman. A uniquely Aotearoa Green New Deal could lay out a vision for people of different backgrounds to come together to embrace innovative indigenous solutions to the climate and environmental crisis. It would be a significant reset of the system to support the self-determination of our indigenous population, which includes their role as kaitiaki of this land. We are a unique country, with a unique founding document. Meaningful shared decision making between Maori and non-Maori, set out in our own New Green deal, would create world-leading systems change.

First steps in this direction are being made in the conservation sector where Māori have led a number of successful projects on Māori land in partnership with DOC. Such successes have been recognised and highlighted in the recently released New Zealand Biodiversity Strategy Te Mana o te Taiao, which outlines an intention to scale up the Māori-led and community-led approach to other areas of biodiversity regeneration.

Another promising approach is the devolving of environmental goal setting and monitoring to Iwi and hapu. This has happened with the recent devolution of the Waikato Regional Council’s Lake Taupo monitoring functions to the local iwi, in a first for a Regional Council in Aotearoa.

Such initiatives could provide a great model for expanding such iwi-led approaches to the creation of more ‘good green jobs’. Both people in government, and everyday New Zealanders can further explore what genuine co-creation involves in the environmental space. It can be as simple as supporting Māori leadership and pioneering models first and then adopting them more widely over time.

Making it work for communities

As Naomi Klein has written of the quest for a Green New Deal in the USA, it is crucial to draw out the connections between the environmental imperatives and the much needed improvement it could present for working class lives, in ways that capture the public imagination. In Klein’s view this task “will take a massive exercise in participatory democracy.”

Similarly, If we are to successfully implement a Green New Deal in New Zealand, it will be important that a large group of people come to think about it as something that will lead to better lives for all of us. Building strong support for change takes commitment to solutions that are upstream and grounded in the everyday needs of all people, not simply the most vocal or currently privileged.

This is how to ensure green growth helps people where it counts. Co-creating solutions at an early stage (e.g. community budget setting, citizen assemblies), supporting Māori self determination and environmental goal setting, and giving more real power to communities in decision-making, will increase the support and buy-in from the public and ensure the policy works in the local context and for all our communities. In short, this involves rethinking our economy, our institutions, our social structures, and even our democracy. Top-down solution building is the work of yesterday, not the work for today or the future.

No comments:

Post a Comment