Published 31st October 2021

Credit: Courtesy of TASCHEN

The witch isn't dead: New book explores witchcraft's rebellious history -- and modern transformation

Written by Marianna Cerini, CNN

Look up "witches" and you might see any of a number of depictions: ugly old ladies and young, sensual temptresses; antiheroes and aspiring role models; evil creatures mixing deadly potions and righteous sorceresses helping girls find their way (a la Glinda the Good Witch in "The Wizard of Oz").

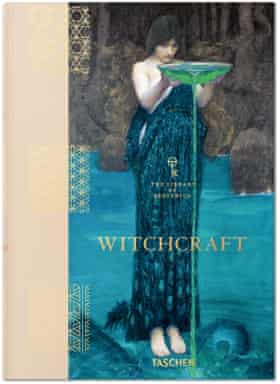

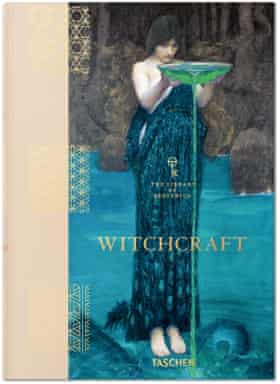

A new title from Taschen's Library of Esoterica aims to explore this wealth of complex identities in a visually vibrant volume that isn't so much a book as it is a spellbinding tribute to a figure and a practice that are as old as time.

'Last Night in Soho' costume designer on creating Edgar Wright's frightful fashion flick

"Witchcraft" offers a deep dive into the many facets of a centuries-old tradition in the Western world, weaving more than 400 classic and contemporary artworks with essays and interviews by what editor Jessica Hundley describes as "a diverse coven of writers, scholars and modern-day practitioners, each embracing the practice in their own individual ways."

In "Witches' Sabbath," artist Jacques de Gheyn II depicts the sabbath with a pen-and-ink drawing of a swirling cauldron. Credit: Courtesy of TASCHEN

"I wanted to present witchcraft through symbolism and art but also fresh, personal perspectives," Hundley explained in a phone interview. "So much of the esoteric is often shrouded in secrecy and weighed down by stigma. With 'Witchcraft,' we worked collaboratively on introducing the subject in a way that felt inclusive and less intimidating."

Clocking in at 500-plus pages, the compendium spans the history of witchcraft and the representation of witches in literature and fairy tales; the tools of the craft and the rituals that have long been part of it. There are also sections dedicated to fashion, creative media and the witch in films and pop culture.

A history of feminine energy and rebellion

While the word "witch" has its etymological roots (wicce) in Old English, the lineage of the 'Western witch' can be traced back to Greek mythology and the earliest folk traditions of Egypt, northern Europe and the Celts.

Each culture represented the mystical figure differently, yet some of her traits recurred across geographically widespread countries: a witch was a powerful goddess, often associated with home and love, but also death and magic. Above all, she was a signifier of complex femininity.

William Holbrook Beard, "Lightning Struck a Flock of Witches," United States, Date Unknown. Beard depicts a fantastical view of stormbound witches in flight -- the coven sent reeling from a flash of close lightning.

Credit: Gene Young/Smithsonian American Art Museum/Courtesy of TASCHEN

"The iconography of the witch, while shifting over the centuries, has always revolved around the idea of feminine power, and reflected society's changing attitudes towards it," said the book's co-editor, Pam Grossman, in a phone interview.

In the 11th century, as male-centered Christianity spread across Europe, perceptions of femininity changed.

So-called witches (often any woman who strayed from the prescriptions of monotheistic religion) began to be considered outliers within their communities, feared and isolated for their supposed connection with the devil.

By the 14th century, the collective imagination had recast witches into heretical outcasts. For the next three centuries, witch hunts and executions -- including the Salem trials of 1692 -- would sweep both the Old and New Worlds.

In Kiki Smith's work "Pyre Woman Kneeling," a bronze female figure tops a pyre. The statue commemorates women who were burned for witchcraft.

Credit: Martin Argyroglo/Courtesy of TASCHEN

"The image of the witch that's been crystallized in our minds -- that of a diabolical, frightening woman -- was born out of this exact period," said Grossman, who is also a writer, curator and teacher of magical practice. "The advent of the printing press, in particular, really helped popularize it. What she really was, of course, was even scarier: a threatening woman."

Indeed, what emerges from "Witchcraft" is that witches and their practice have long been a metaphor for women who want authority over their own lives (the coven, essentially a female-run community, is part of this metaphor, too). Browsing the book, which features works by names as diverse as Auguste Rodin, Paul Klee and Kiki Smith, it's hard not to notice how so many of them represented witches as fierce, powerful creatures even as they were being shunned by society.

Whether aging hags or hypersexual young beauties, they're the embodiment of a rebellious spirit that "wants to subvert the status quo," Grossman said.

A resurgence of witches

In the 18th and early 19th century, as the persecution of witches ended (at least in the Western world) and witchcraft started to be recognized as the last vestige of pagan worship, the magical figure was recast once again. This time, she was made into a fantastical subject as well as a symbol of female rage, independence, freedom and feminism.

Behind the latter "rebranding" was the suffragette movement, which used the archetype of the witch as the persecuted "other," an example of patriarchal oppression.

Witchcraft gained popularity again in the 1960s as second-wave feminism saw witches and their covens as expressions of feminine power and matriarchy (on the activism side, there was even a group of women who, in 1968, founded an organization called W.I.T.C.H).

The Boston-based group, W.I.T.C.H Boston, gather September 19, 2017, on Boston Common for a rally opposing the end of the DACA program.

Credit: Lauren Lancaster/Courtesy of TASCHEN

The practice made another comeback during the 1990s, following the Anita Hill hearings and the rise of third-wave feminism; and then again in the wake of Donald Trump's 2016 election and the #MeToo movement.

Over the past four years, the practice has gone mainstream, spurring articles, podcasts and Instagram accounts.

"I think that for a lot of women and, increasingly, queer and nonbinary people, the witch has come to represent an alternative to institutional power, as well as a way to tap into their spirituality in a way that isn't mediated by someone else," Grossman said.

"Witchcraft is a means by which you can feel like you have some agency in the world. And because so much of it is about creating your own rituals, it allows individuals from different backgrounds to take part in it on their own terms."

Anthony "Bones" Johnson, "Lilith," England/Ibiza 2018. In his last series, Anthony "Bones" Johnson painted scenes that honor the alchemical forces of nature and the power of women.

Credit: Courtesy of TASCHEN

The witchy narrative has evolved on screen, too, and "Witchcraft" dedicates its last pages to that.

From the scary Wicked Witch of the West in "The Wizard of Oz" to the beautiful Samantha of "Bewitched" and the tenacious Sabrina of the "Chilling Adventures of Sabrina" (which couldn't be more far removed from the original show starring Melissa Joan Hart), the witch has shifted from villain to protagonist, and from someone you would be afraid of to someone you might aspire to be.

Women have been overlooked in the history of alcohol. This author set out to change that

"Whether they instill fear, seduce, use violence or act for the greater good, the way visual arts portray witches is always reflective of the cultural moment they're part of,'' Hundley said. What has remained unchanged through the centuries, she noted, is that the very nature of the witch is to contain all of these archetypes within her at all times.

"The witch is in a state of constant evolution," she said. "She's a shapeshifter."

"Witchcraft" is available in Europe now and will be released next month in the US.

Add to queue: Empowering witches

READ: "The Once and Future Witches" (2020)

Witchcraft and activism are woven together in this Gothic fantasy novel by Alix E. Harrow, set in an alternate America where witches once existed but no longer do The year is 1893, and the estranged Eastwood sisters -- James Juniper, Agnes Amaranth and Beatrice Belladonna -- join the suffragists of New Salem while beginning to awaken their own magic, transforming the women's movement into the witches' movement.

BROWSE: "Major Arcana: Portraits of Witches in America" (2020)

Frances F. Denny's photographic project "Major Arcana: Witches in America" is an ambitious visual document of the modern face of witchcraft. Denny spent three years meeting and photographing a diverse group of witches around the US, capturing the various ways "witch-ness" expresses itself.

WATCH: "Motherland: Fort Salem" (2020)

Witches become superheroes in this action-packed series, currently in its second season. Three young sorceresses conscripted into the US Army -- Raelle Collar, Abigail Bellweather and Tally Craven -- use their supernatural tactics and spells to defend the country against a terrorist organization known as the Spree, a witch resistance group.

LISTEN: "Between the Worlds" (2018-present)

Host Amanda Yates Garcia discusses tarot, psychology, mythology, pop culture, witchcraft, magic, art and history alongside a series of special guests, in a podcast that aims to explore the many expressions of the practice.

WATCH: "American Horror Story: Coven" (2013)

Set in post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans, the third season of the FX horror anthology series "American Horror Story" centers on a coven of witches descended from the survivors of the Salem trials as they fight for survival against the outside world. The show deals with femininity and race, as well as issues around modern feminist theories and practice.

Top image: Titled "Ritual," this 2019 work by photographer Psyché Ophiuchus shows a ceremonial circle taking place in Fairy Glen on the Isle of Skye at dusk.

‘Joyously subversive sex goddesses’: the artists who gave witches a spellbinding makeover

We all know what a witch looks like. A gnarled old face full of warts with teeth missing and bright green skin. Then there’s the long black coat, the tall black hat and let’s not forget the sizable crooked nose, sniffing the fumes rising from a bubbling cauldron in a room festooned with cobwebs.

But that’s not what witches look like at all, or at least not according a hefty new art book being published in time for Halloween. In this compendium of witchy women, from Renaissance paintings to modern Wicca, the caricature of the evil hag is turned upside down. Witchcraft, the latest volume in Taschen’s Library of Esoterica, finds evidence from artists as diverse as Auguste Rodin and Kiki Smith for its revisionist view that witches are typically young, glamorous practitioners of highly sexualised magick. The cover painting, by Victorian artist JW Waterhouse, depicts the ancient enchantress Circe in pale, red-lipped pre-Raphaelite ecstasy – and the fun just keeps coming. The witches here are powerful feminist sex goddesses whose rites and incantations are joyously subversive.

There’s nothing respectably academic about Witchcraft. One of its editors is herself a witch and it includes photographs of 1960s and 70s Wiccans – practitioners of modern pagan magick. Consecration of Wine, Stewart Farrar’s misty monochrome 1971 photograph, portrays his wife, Janet, bare-breasted, filling a raised chalice in a modern ritual “meant to invoke the sacred union of male and female – the alchemical wedding”. Another photo shows a group known as the “Farrar coven” lying on their backs to form a pentagram in a British back garden in 1981.

Not one you’ll see this Halloween … a highly symbolically decorated witch by Oh, featured in the book Witchcraft. Photograph: © Vic Oh

Thousands of women were slain after being accused of witchcraft. Don’t they deserve more than the evil cackling hag stereotype? A powerful new book blows away the satanic baby-eating myths

Jonathan Jones

Wed 27 Oct 2021 13.34 BST

Thousands of women were slain after being accused of witchcraft. Don’t they deserve more than the evil cackling hag stereotype? A powerful new book blows away the satanic baby-eating myths

Jonathan Jones

Wed 27 Oct 2021 13.34 BST

We all know what a witch looks like. A gnarled old face full of warts with teeth missing and bright green skin. Then there’s the long black coat, the tall black hat and let’s not forget the sizable crooked nose, sniffing the fumes rising from a bubbling cauldron in a room festooned with cobwebs.

But that’s not what witches look like at all, or at least not according a hefty new art book being published in time for Halloween. In this compendium of witchy women, from Renaissance paintings to modern Wicca, the caricature of the evil hag is turned upside down. Witchcraft, the latest volume in Taschen’s Library of Esoterica, finds evidence from artists as diverse as Auguste Rodin and Kiki Smith for its revisionist view that witches are typically young, glamorous practitioners of highly sexualised magick. The cover painting, by Victorian artist JW Waterhouse, depicts the ancient enchantress Circe in pale, red-lipped pre-Raphaelite ecstasy – and the fun just keeps coming. The witches here are powerful feminist sex goddesses whose rites and incantations are joyously subversive.

There’s nothing respectably academic about Witchcraft. One of its editors is herself a witch and it includes photographs of 1960s and 70s Wiccans – practitioners of modern pagan magick. Consecration of Wine, Stewart Farrar’s misty monochrome 1971 photograph, portrays his wife, Janet, bare-breasted, filling a raised chalice in a modern ritual “meant to invoke the sacred union of male and female – the alchemical wedding”. Another photo shows a group known as the “Farrar coven” lying on their backs to form a pentagram in a British back garden in 1981.

Pyre Woman Kneeling by Kiki Smith commemorates women who were burned for witchcraft. Photograph: Martin Argyroglo/La Monnaie de Paris

Witchcraft’s thesis is completely convincing. In scouring the history of art to back up their modern-pagan perspective, the editors point to something remarkable. Artists over the centuries have created images of the witch far removed from the cackling stereotype established by witch trials and remembered in popular culture today without any respect for the women (and some men) who were killed in these mockeries of justice.

A work by Kiki Smith tries to show reverence to the victims of the witch-hunters. Her sculpture of a naked witch kneels on an unlit pyre, spreading her arms in triumph: a woman resurrected from this history of misogyny. Typically – at the height of the “witch craze”, which lasted from around 1570 to 1660 – people accused of witchcraft were older women who lived in poverty at the margins of rural communities. Better-off neighbours feared their supposed magical vengeance. Investigators such as England’s infamous Witchfinder General, Matthew Hopkins, believed the witches met at a midnight sabbath and ate babies, exchanged animal familiars or “imps”, and had sex with Satan.

This stereotype was just as unrelated to reality as medieval Europe’s murderous caricature of Jewish people. Yet leafing through this book, you quickly see that even as elderly rural women were being demonised and burned alive, Renaissance artists saw witchcraft in a very different way. They associated it with desire, enchantment and female power.

One spread in the volume features Satisfaction – a 1984 painting by Shimon Okshteyn of a triumphant post-coital “modern siren” as the caption has it – exulting in presumably witchy erotic power. It is juxtaposed with a 15th-century German painting by an unknown artist of a naked woman performing a spell in her room. A man appears at the door, spying on the nude witch. He’s in big trouble, you can’t help feeling. He’s going to get a magical punishment simply for seeing this witch dancing at her private rituals. But warts, ugly nose, a familiar? No, this is one of the most sensual nudes in early Renaissance art.

Witchcraft’s thesis is completely convincing. In scouring the history of art to back up their modern-pagan perspective, the editors point to something remarkable. Artists over the centuries have created images of the witch far removed from the cackling stereotype established by witch trials and remembered in popular culture today without any respect for the women (and some men) who were killed in these mockeries of justice.

A work by Kiki Smith tries to show reverence to the victims of the witch-hunters. Her sculpture of a naked witch kneels on an unlit pyre, spreading her arms in triumph: a woman resurrected from this history of misogyny. Typically – at the height of the “witch craze”, which lasted from around 1570 to 1660 – people accused of witchcraft were older women who lived in poverty at the margins of rural communities. Better-off neighbours feared their supposed magical vengeance. Investigators such as England’s infamous Witchfinder General, Matthew Hopkins, believed the witches met at a midnight sabbath and ate babies, exchanged animal familiars or “imps”, and had sex with Satan.

This stereotype was just as unrelated to reality as medieval Europe’s murderous caricature of Jewish people. Yet leafing through this book, you quickly see that even as elderly rural women were being demonised and burned alive, Renaissance artists saw witchcraft in a very different way. They associated it with desire, enchantment and female power.

One spread in the volume features Satisfaction – a 1984 painting by Shimon Okshteyn of a triumphant post-coital “modern siren” as the caption has it – exulting in presumably witchy erotic power. It is juxtaposed with a 15th-century German painting by an unknown artist of a naked woman performing a spell in her room. A man appears at the door, spying on the nude witch. He’s in big trouble, you can’t help feeling. He’s going to get a magical punishment simply for seeing this witch dancing at her private rituals. But warts, ugly nose, a familiar? No, this is one of the most sensual nudes in early Renaissance art.

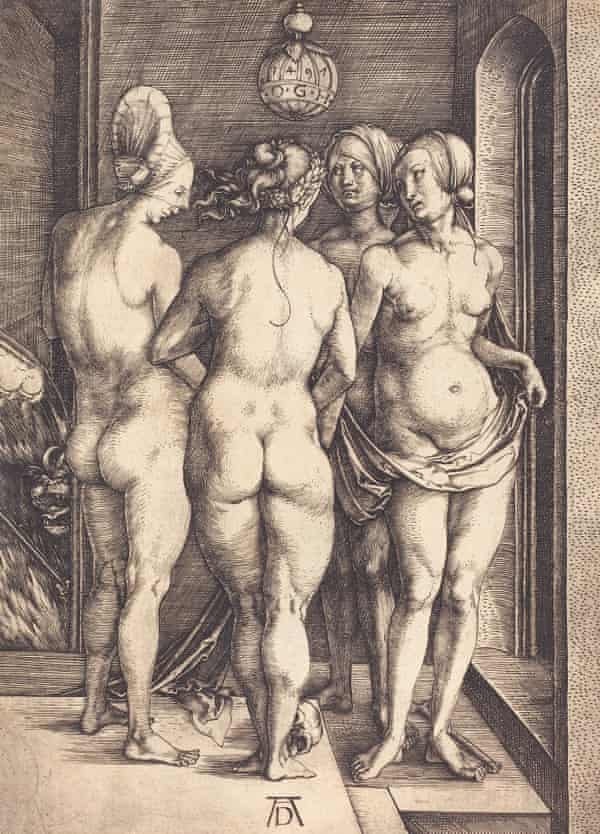

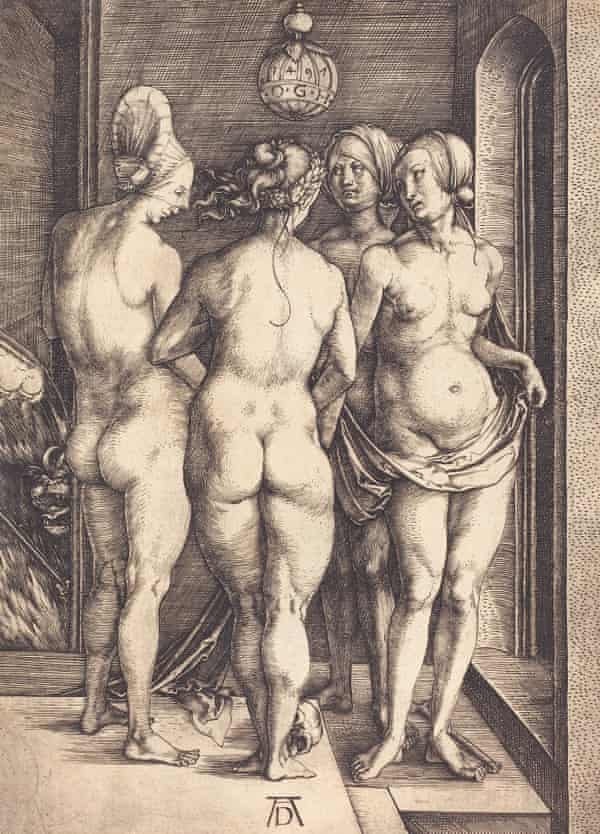

The Four Witches by Albrecht Dürer, 1497.

Photograph: © National Gallery of Art, Rosenwald Collection

That stress on the allure and attraction of witches is even more explicit in the work of the great German Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer. In 1497, Dürer made The Four Witches, an engraving that depicts fleshy nudes dancing in a round. They are delineated with a boldness he learned on a trip across the Alps to Venice. There he encountered not just the city’s sex workers who also worked as artist’s models, but the new classically influenced Italian art with its cult of the human body. But Dürer’s own desires make him anxious. Even as he draws these women naked – as if picturing respectable Nuremberg frauen with their clothes off – he seems to sense they are witches. At the back of the room, an open door reveals the devil, his fanged mouth hanging open as he watches his minions from a cellar that has become a portal of hell.

Even when he does portray an aged witch riding backwards on a goat, an image much more closely connected to the witch-hunt stereotype, Dürer gives her a retinue of Renaissance cupids to complicate things. He is not really interested in persecuting old peasants but in exploring the artistic and moral tensions between his love of the flesh and his fear of sin.

A painting by his pupil Hans Baldung Grien gives two witches an even more gracious youth and beauty. They pose glamorously, more like models than agents of the macabre. Another great German 16th-century artist, Lucas Cranach, was most paradoxical of all. He painted fetishistically gloved or bonily nude women as charismatic beings of sexualised power – while, as a magistrate, he would have been personally involved in executing “witches”. In the sado-masochist fantasy world of his art, he desires everything that in real life he persecuted.

If artists could enjoy the witch as much as this – while women accused of witchcraft were being burned for the threat they were thought to pose to Christian society – itis little wonder art became ever more enchanted by the subject once the persecution ceased. By the 18th century, burning witches seemed like cruel superstitious nonsense. Instead, they became fuel for fantasy. Erotic drawings by Rodin and his kinky Belgian contemporary Félicien Rops imagine other uses for broomsticks than flying. In a Rodin sketch from about 1890, a witch faces us with her naked legs apart, rubbing her broom against her body with pleasure. Rops, too, depicts a young witch with a broomstick between her legs while she reads from her spell book wearing only her stockings.

That stress on the allure and attraction of witches is even more explicit in the work of the great German Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer. In 1497, Dürer made The Four Witches, an engraving that depicts fleshy nudes dancing in a round. They are delineated with a boldness he learned on a trip across the Alps to Venice. There he encountered not just the city’s sex workers who also worked as artist’s models, but the new classically influenced Italian art with its cult of the human body. But Dürer’s own desires make him anxious. Even as he draws these women naked – as if picturing respectable Nuremberg frauen with their clothes off – he seems to sense they are witches. At the back of the room, an open door reveals the devil, his fanged mouth hanging open as he watches his minions from a cellar that has become a portal of hell.

Even when he does portray an aged witch riding backwards on a goat, an image much more closely connected to the witch-hunt stereotype, Dürer gives her a retinue of Renaissance cupids to complicate things. He is not really interested in persecuting old peasants but in exploring the artistic and moral tensions between his love of the flesh and his fear of sin.

A painting by his pupil Hans Baldung Grien gives two witches an even more gracious youth and beauty. They pose glamorously, more like models than agents of the macabre. Another great German 16th-century artist, Lucas Cranach, was most paradoxical of all. He painted fetishistically gloved or bonily nude women as charismatic beings of sexualised power – while, as a magistrate, he would have been personally involved in executing “witches”. In the sado-masochist fantasy world of his art, he desires everything that in real life he persecuted.

If artists could enjoy the witch as much as this – while women accused of witchcraft were being burned for the threat they were thought to pose to Christian society – itis little wonder art became ever more enchanted by the subject once the persecution ceased. By the 18th century, burning witches seemed like cruel superstitious nonsense. Instead, they became fuel for fantasy. Erotic drawings by Rodin and his kinky Belgian contemporary Félicien Rops imagine other uses for broomsticks than flying. In a Rodin sketch from about 1890, a witch faces us with her naked legs apart, rubbing her broom against her body with pleasure. Rops, too, depicts a young witch with a broomstick between her legs while she reads from her spell book wearing only her stockings.

Boston WITCH by Lauren Lancaster, 2017. WITCH was a 1960s anti-war group resurrected in 2016 to protest against US immigration practices. Photograph: Lauren Lancaster

Advertisement

In modern art by women, however, the witch has been reclaimed as a figure of power and freedom. Francesca Woodman poses eerily in a ruinous room in Providence, Rhode Island, almost floating, weaving the air with her arms, as if performing a spell. She seems to be conjuring up the inhabitants of this haunted house. Maybe she’s summoning the victims of New England’s bygone witch-hunts. Betye Saar’s installation Window of Ancient Sirens uses mirrors and fire to invoke her demon sisters. Her art openly embraces African and Caribbean magical traditions to animate objects and re-enchant modern life.

Advertisement

In modern art by women, however, the witch has been reclaimed as a figure of power and freedom. Francesca Woodman poses eerily in a ruinous room in Providence, Rhode Island, almost floating, weaving the air with her arms, as if performing a spell. She seems to be conjuring up the inhabitants of this haunted house. Maybe she’s summoning the victims of New England’s bygone witch-hunts. Betye Saar’s installation Window of Ancient Sirens uses mirrors and fire to invoke her demon sisters. Her art openly embraces African and Caribbean magical traditions to animate objects and re-enchant modern life.

The cover of Witchcraft, featuring JW Waterhouse’s Circe Invidiosa. Photograph: Taschen

Even the stereotype of the evil black-clad old witch is transformed by feminist art. Members of the Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell (WITCH) – originally founded by anti-war protesters in 1968 and recreated in 2016 – hide their identities under their pointy hats in a photograph by Lauren Lancaster.

But the fun of Witchcraft is its enthusiastic embrace of every side of its subject, from the sublime to the silly. You don’t have to buy a stuffed goat, set up an altar in your garage and invite the neighbours to a swinging sabbath to agree that witches get a rough ride three centuries after the European witch-hunt ended. At Halloween, most of the monsters we delight in have no connection to reality. Vampires, ghosts and Frankenstein’s monster are creatures of the imagination. But tens of thousands of real human beings were put to death in the name of the witch stereotype that is touted around for fun at this time of year. And that could well be the most horrifying thing about Halloween.

The Library of Esoterica: Witchcraft, edited by Jessica Hundley and Pam Grossman, is published by Taschen on 31 October (£30).

Even the stereotype of the evil black-clad old witch is transformed by feminist art. Members of the Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell (WITCH) – originally founded by anti-war protesters in 1968 and recreated in 2016 – hide their identities under their pointy hats in a photograph by Lauren Lancaster.

But the fun of Witchcraft is its enthusiastic embrace of every side of its subject, from the sublime to the silly. You don’t have to buy a stuffed goat, set up an altar in your garage and invite the neighbours to a swinging sabbath to agree that witches get a rough ride three centuries after the European witch-hunt ended. At Halloween, most of the monsters we delight in have no connection to reality. Vampires, ghosts and Frankenstein’s monster are creatures of the imagination. But tens of thousands of real human beings were put to death in the name of the witch stereotype that is touted around for fun at this time of year. And that could well be the most horrifying thing about Halloween.

The Library of Esoterica: Witchcraft, edited by Jessica Hundley and Pam Grossman, is published by Taschen on 31 October (£30).

TASCHEN IS AN ART BOOK PUBLISHER

No comments:

Post a Comment