USSA

Empire of Lies

Thirty years after the fall of the Soviet Union, the country's assault on truth remains all too relevant.

By Roland Merullo

The first time I headed home from working in the USSR, in early October of 1977, a colleague and I left the country on a train that traveled overnight from Leningrad to Helsinki. Just shy of the Finnish border, somewhere after midnight, the brakes squealed and the train jolted to a halt. My friend and I waited there in our two-person coupe, anxious to cross over into freedom. After half an hour or so, there was a quick knock, the coupe door was thrown open, and in strode a pair of no-nonsense Border Guard officers in their green uniforms and maroon epaulets.

Against my skin, inside the front of my long-sleeved shirt, were hidden several pen-and-ink drawings on heavy paper. The drawings had been made by a Soviet friend, a veteran of the Gulag, a damaged man, and they depicted Vladimir Lenin in various insulting poses. The friend had begged me to carry them out of the country and, perhaps foolishly, I’d agreed, not having any idea what I’d ultimately do with them.

I sat on the edge of the bunk while the officers ran their eyes over every corner of the coupe and fired questions at me in Russian. Where were we going? What had we been doing in the USSR? Were we carrying any contraband—icons, gold, caviar, samizdat? Throughout this unpleasant farewell, I could feel the drawings against my chest. My hands were sweating. I could hear the sounds of voices and dogs barking just outside the coupe windows, and could see flashlight beams angling there in the darkness. When they were finished, the officers grunted suspiciously and slammed the door behind them, but the activity outside went on for what seemed like another hour. Eventually, things quieted down, the train jerked into motion again, and it wasn’t long until we crossed the border into a very different land.

The border guards would no doubt have detained and questioned me if they’d discovered the drawings. The soldiers outside and their trained German Shepherds had been searching beneath the rail cars, looking for citizens so desperate to leave their troubled homeland that they’d cling there, risking arrest, injury, or death. The intensity of the indoor questioning and the care taken in the outdoor search gave the lie to what so many Soviets had told us over the months we’d worked there: that they were free to express themselves in any way that pleased them and were able to travel anywhere they wanted. Finland, France, Africa, America—it didn’t matter; they were as free as we were to wander the globe and speak our minds.

When I think of the breakup of the Soviet Union—a place where I lived and worked for 28 months between 1977 and 1990—I think of that nervous moment on the train, and I remember, all too clearly, the assault on truth we’d encountered in the country we were about to leave.

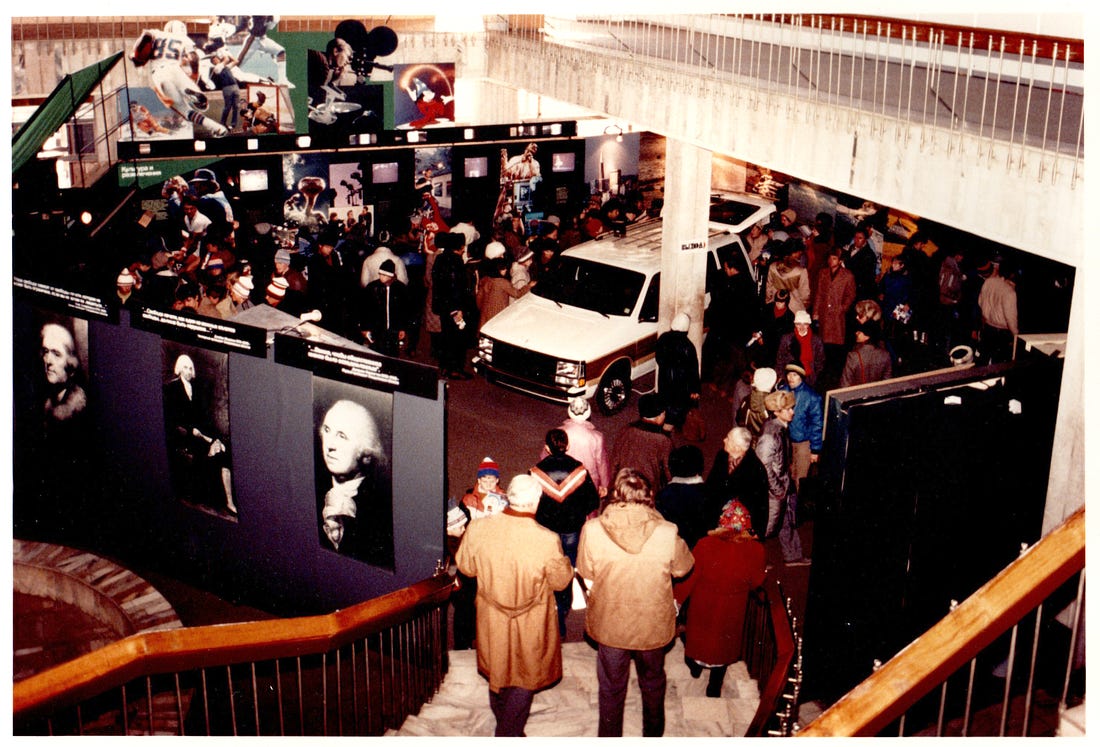

That train trip marked the end of my first tour in the USSR, working on United States Information Agency traveling cultural-exchange exhibitions that were visited by as many as 15,000 people per day. The 28 months I’d eventually spend in the Soviet Union were broken up into three long tours: seven months in 1977 as exhibit guide; fourteen months in 1987-88 as General Services Officer; and seven months in 1989-90 as Field Director.

In those three very different positions, I interacted with a broad spectrum of the Soviet population: exhibit visitors young and old, ordinary laborers, police, customs officials, and high-ranking Party officials. By the end of my service there, I spoke Russian fluently and had been soaked from head to toe in the life, culture, and politics of the place. I’d also watched it evolve from the harsh days of Brezhnev-style communism to the vastly more open-minded rule of Gorbachev. Through it all, I observed and listened to the way the truth was buried, twisted, manipulated, and eventually, however briefly, allowed to see the light of day.

As they left our exhibit, Soviet visitors were given the opportunity to write in a “comment book.” In 1977, many of the comments reflected Communist Party propaganda. Here are some typical examples: Why do your guides lie about your country and ours? Isn’t it true that, if your employees live in private homes, they must be the sons and daughters of wealthy capitalists? We know that the exhibits shown here do not honestly reflect the horrible conditions under which most Americans live. During my first tour, I briefly had a Siberian girlfriend. In our last conversation, not long before I left for home, she told me, “I feel so sorry for you, having to return to America. It must be like going back to prison.”

By the late eighties, all that had changed. The truth had been let out of the tight red bag in which the apparatchiki had kept it, and, among the few remaining hardline comments in the exhibit book, we’d find many like these, that stick in my memory: You live on the moon. We live in shit. And, It will take us 500 years to catch up to life in the West. And, Why have we been lied to all this time?

What happened next reminds me of a line spoken by Mike, one of Hemingway’s characters in The Sun Also Rises. When asked how he went bankrupt, Mike replies, “Two ways. Gradually and then suddenly.” Well into the 1980s, though the Soviet economy was pitifully weak, not even the most prescient scholars could have predicted the abrupt unraveling of the USSR’s seven-decade system of sophisticated propaganda backed by torture, murder, and strict prohibitions against foreign travel and exposure to Western media. And yet, that sudden unraveling is exactly what occurred.

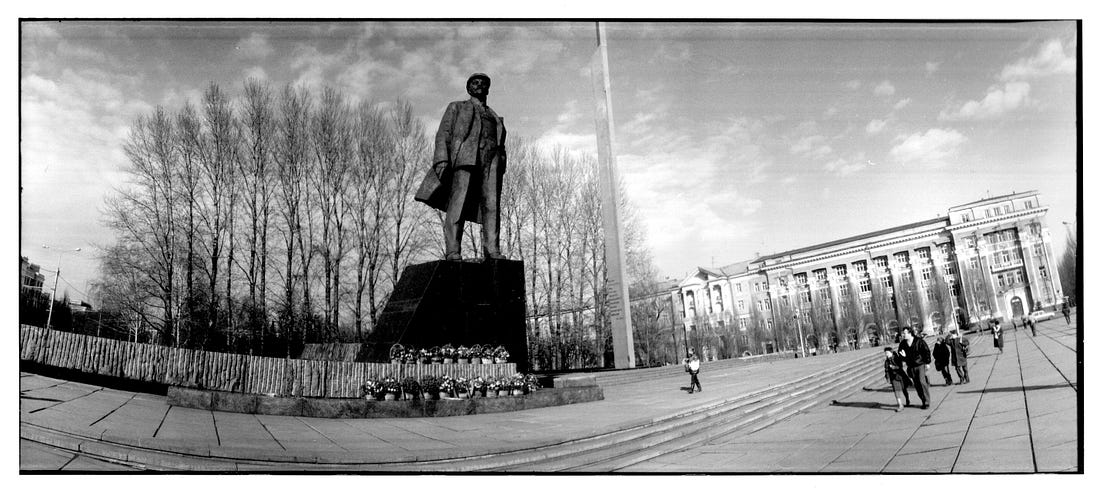

I was working in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) when the Berlin Wall fell in 1989. It seemed the perfect metaphor for the ensuing collapse of the structure of lies on which the Soviet Union had been constructed: that Party leaders were building a just society and not lining their own pockets; that life in the USSR was far better than life in the Russia that preceded it and much preferable to life in the West; that Soviet goods were a match for, or even superior to, those produced in the United States; that there was no Gulag, no censorship, no crime, no corrupt courts or police, no travel restrictions; that all the evil in the world could be traced to the capitalist impulse.

This Sunday marks thirty years since the collapse of the onion-domed palace of mendacity once called the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics—a collapse which filled so many of us with hope until Vladimir Putin arrived on the scene. That nation’s relatively brief lifespan has led me to believe that the truth exerts a kind of invisible pressure on human constructs, continuously leaning against us as individuals and societies, pushing us in the direction of honesty and harmony.

Of course, those whom the popular psychiatrist M. Scott Peck labeled “people of the lie” are continuously pushing back, often employing propaganda and violence in an effort to design and maintain a false narrative, and bend others to their will. The degree to which violence is always necessary for the perpetuation of their lies makes me envision the truth as something tidal. It recedes but never disappears, and its inevitable return can be prevented only with great effort and artificial constraints.

Dictatorships cause an immeasurable amount of suffering on this earth, but, in many cases, they don’t last. Whether it’s the junta in Argentina or the iron fist of Nicolae Ceaușescu in Romania, Idi Amin’s reign of terror in Uganda or the closed nation built by Lenin and Stalin and supported by their heirs, the tidal pressure of the truth eventually erodes the dictator’s power and breaks apart the system. Sometimes, as is the case in Iran, Burma, and Cambodia, and now in Russia, that breakage leads only to new lies, a new boss, more misery. At other times, as in Uruguay and what was once called East Germany, the collapse lets in a flood of light and the society blossoms and thrives.

It also happens—and perhaps this is happening in our country now—that a healthy society’s truthful foundation can undergo a slow erosion. In such cases, ordinary citizens begin to question even the idea of truth, whether it’s the evolving and complicated truth of science, fairly-counted votes in a national election, or the facts presented by multiple respected media outlets.

The human experience is painfully complex and, as a result, many of us long for simple answers. Autocrats on both right and left are more than happy to provide those simple answers if it serves their own purposes. First, they muddy the waters with conspiracy theories and disinformation, and then they construct their own narrative, based on a foundation of lies but presented with great conviction, and backed up by mockery, censorship, duplicity, and violence.

I watched as the truth, kept from the Soviet motherland for seventy years, flooded into view like a hopeful tide, and was then shoved away again, by Putin and his minions, with murder and treachery. It waits there, though, always pushing toward the light. I feel for those truth-tellers—like the heroic Alexei Navalny—who suffer terribly in the meantime, and I worry about my own country, flawed as it is but still beautifully free, as the tide of truth ebbs slowly away from our shores. Steeped as I have been in the sordid history of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, I sometimes lie awake at night, remembering the suffering and deprivation I witnessed there, replaying the lies, and wondering, as the truth is assaulted here in America day after day, what will become of us.

Roland Merullo is the author of 16 novels and writes an essay series called On the Plus Side. More of his work is available at RolandMerullo.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment