Leyland Cecco in Toronto

THE GUARDIAN

Fri, 10 March 2023

Photograph: The Canadian Press/Alamy

Throughout the summer and into the fall, members of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation ventured out on to the land as they do every year, hunting and fishing the streams and boreal forest of their community in western Canada.

Over those same months last year, however, toxic water had been leaking from an oil sands operations upriver.

It wasn’t until recently, when Chief Allan Adam got a call from a neighbouring First Nation, that he realized the danger his community could be in: mine waste had been seeping from four tailings ponds for months.

When he called them, company officials and the province’s energy regulator both confirmed the leak – but neither had warned the community when they learned of the issue nine months ago.

Adam is now prepared to battle both Imperial Oil and Alberta’s energy regulator, alleging they “covered up unprecedented failures” of the company’s containment ponds, in what is now believed to be one of the largest tailings leaks in Alberta history.

“They’re both up against the wall right now. They were caught red-handed. The trust is gone. There’s no way you can come back from that. And we’ll always have what happened in the back of our mind, whenever we’re out on the land,” he said. “You can’t ever forget about something like this.”

Fri, 10 March 2023

Photograph: The Canadian Press/Alamy

Throughout the summer and into the fall, members of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation ventured out on to the land as they do every year, hunting and fishing the streams and boreal forest of their community in western Canada.

Over those same months last year, however, toxic water had been leaking from an oil sands operations upriver.

It wasn’t until recently, when Chief Allan Adam got a call from a neighbouring First Nation, that he realized the danger his community could be in: mine waste had been seeping from four tailings ponds for months.

When he called them, company officials and the province’s energy regulator both confirmed the leak – but neither had warned the community when they learned of the issue nine months ago.

Adam is now prepared to battle both Imperial Oil and Alberta’s energy regulator, alleging they “covered up unprecedented failures” of the company’s containment ponds, in what is now believed to be one of the largest tailings leaks in Alberta history.

“They’re both up against the wall right now. They were caught red-handed. The trust is gone. There’s no way you can come back from that. And we’ll always have what happened in the back of our mind, whenever we’re out on the land,” he said. “You can’t ever forget about something like this.”

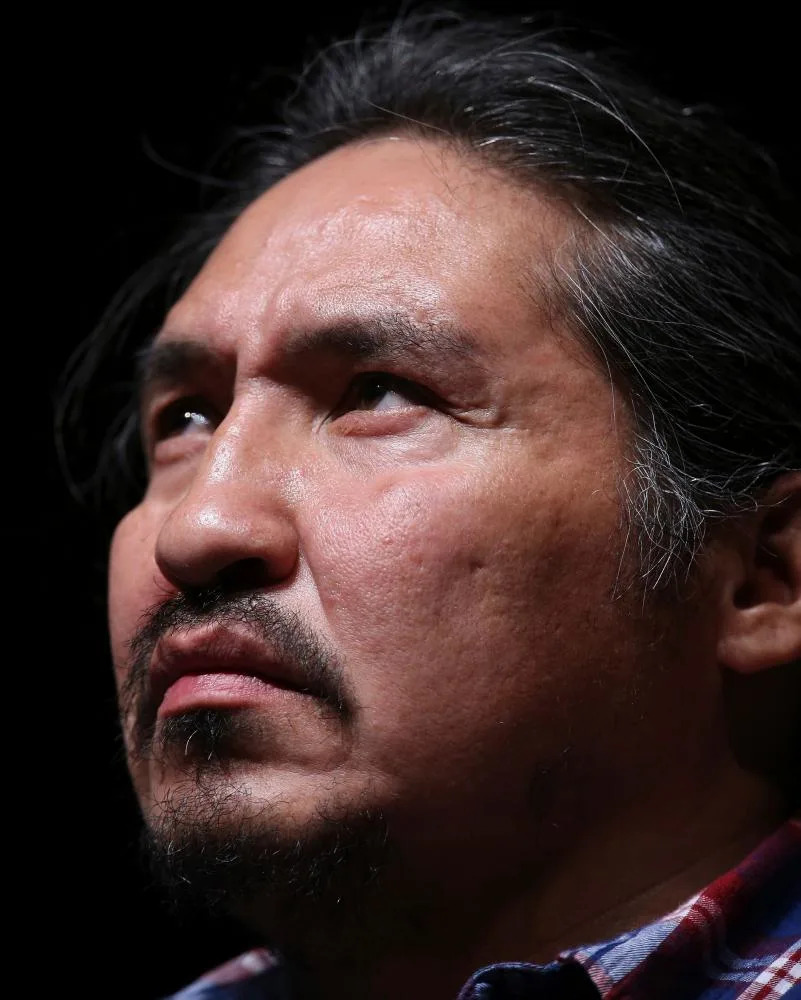

The Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation chief, Allan Adam.

Photograph: Trevor Hagan/Reuters

Calgary-based Imperial Oil notified Alberta’s energy regulator in May that it had discovered discoloured water near the Kearl oil sands project.

The regulator soon concluded the water had come from tailings ponds where the company stored the toxic sludge-like byproducts of bitumen mining. Environmental samples showed high levels of several toxic contaminants, including arsenic, iron, sulphate and hydrocarbon – all of which exceeded provincial guidelines.

Local communities were notified in May of the initial discovery of discoloured water, but not made aware of the regulator’s subsequent findings that containment ponds had failed.

Last month, there was another leak, in which 5.3m litres of tailings water escaped from an overflowing catchment pond. This time, the community was informed two days later.

On Monday, Imperial said the second spill posed no threat to water or wildlife and that it had made “significant progress” in the cleanup efforts.

But the company admits it doesn’t yet know how much toxic tailings water has seeped into the land and water over the last nine months.

Adam says he met with company officials three times during the period, but alleges they never mentioned the leaking tailings pond.

On Monday, Imperial apologized for not communicating with affected communities, admitting it had “fallen short of expectations”.

Despite assurances from the company, residents remain wary. In the municipality of Wood Buffalo, city staff have stopped drawing from Lake Athabasca.

And in Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation, community members have been advised by leadership not to eat any game or fish harvested in the last nine months.

“I just got back from an elders meeting and I told everyone to get rid of whatever you harvested. Throw it out. Don’t even feed it to your dogs,” said Adam, adding the community was waiting on test results of its water supply to determine if it is contaminated.

Imperial Oil has since been hit with both an environmental protection order and a non-compliance order in relation to the leak and the province’s regulator has demanded the company file plans to show how it intends to contain, monitor and remediate the areas affected by the leak.

Canada’s environment minister, Steven Guilbeault, said last week he was “deeply concerned” over revelations toxic water had been leaking into the nearby land and water for months.

Adam met with the the province’s regulator this week, and received an apology from senior staff for their failure to notify his community.

“I told them don’t bother apologizing. We’re well past that. Fix this problem, and show me how you won’t let it happen again.”

He says the inability for residents to harvest from the lands is a violation of the nation’s treaty rights and by not notifying the community of the spill, the company breached its benefit agreement contract with the First Nation.

“I told the company and I told the regulator that a simple phone call would have cost you less than five bucks. A simple phone call,” he said. “Look at what it’s going to cost you now.”

Calgary-based Imperial Oil notified Alberta’s energy regulator in May that it had discovered discoloured water near the Kearl oil sands project.

The regulator soon concluded the water had come from tailings ponds where the company stored the toxic sludge-like byproducts of bitumen mining. Environmental samples showed high levels of several toxic contaminants, including arsenic, iron, sulphate and hydrocarbon – all of which exceeded provincial guidelines.

Local communities were notified in May of the initial discovery of discoloured water, but not made aware of the regulator’s subsequent findings that containment ponds had failed.

Last month, there was another leak, in which 5.3m litres of tailings water escaped from an overflowing catchment pond. This time, the community was informed two days later.

On Monday, Imperial said the second spill posed no threat to water or wildlife and that it had made “significant progress” in the cleanup efforts.

But the company admits it doesn’t yet know how much toxic tailings water has seeped into the land and water over the last nine months.

Adam says he met with company officials three times during the period, but alleges they never mentioned the leaking tailings pond.

On Monday, Imperial apologized for not communicating with affected communities, admitting it had “fallen short of expectations”.

Despite assurances from the company, residents remain wary. In the municipality of Wood Buffalo, city staff have stopped drawing from Lake Athabasca.

And in Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation, community members have been advised by leadership not to eat any game or fish harvested in the last nine months.

“I just got back from an elders meeting and I told everyone to get rid of whatever you harvested. Throw it out. Don’t even feed it to your dogs,” said Adam, adding the community was waiting on test results of its water supply to determine if it is contaminated.

Imperial Oil has since been hit with both an environmental protection order and a non-compliance order in relation to the leak and the province’s regulator has demanded the company file plans to show how it intends to contain, monitor and remediate the areas affected by the leak.

Canada’s environment minister, Steven Guilbeault, said last week he was “deeply concerned” over revelations toxic water had been leaking into the nearby land and water for months.

Adam met with the the province’s regulator this week, and received an apology from senior staff for their failure to notify his community.

“I told them don’t bother apologizing. We’re well past that. Fix this problem, and show me how you won’t let it happen again.”

He says the inability for residents to harvest from the lands is a violation of the nation’s treaty rights and by not notifying the community of the spill, the company breached its benefit agreement contract with the First Nation.

“I told the company and I told the regulator that a simple phone call would have cost you less than five bucks. A simple phone call,” he said. “Look at what it’s going to cost you now.”

No comments:

Post a Comment