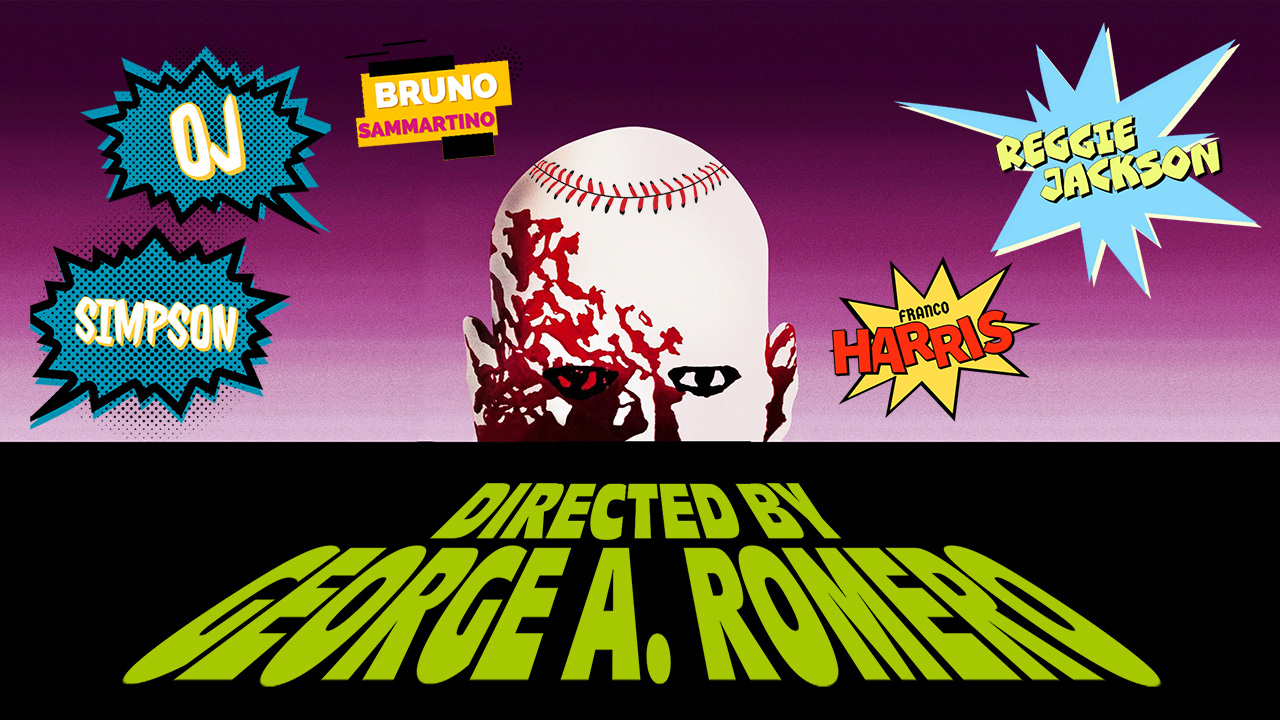

Dan McQuade/Defector (Original Dawn of the Dead poster by Lanny Powers)

By Adam Charles Hart

By Adam Charles Hart

May 3, 2023

In 1973, only five years after releasing Night of the Living Dead, George A. Romero was, in the eyes of the movie industry, washed up. Night was already well on its way from revolting little horror movie to hipster favorite to cult classic to actual classic. But no one saw much money from it—even though, it should be pointed out, it was still playing on the Midnight Movie circuit in 1973. And after failing to replicate Night’s success with subsequent efforts, Romero’s filmmaking troupe split, burdened by debts and frustrated by the mounting difficulties of raising money for another movie.

Romero was on his own for the first time in his career. He was in Pittsburgh, about as far as you can get from Hollywood, and he wanted to work. He wanted to keep making movies. He and his collaborators had built a very successful business making commercials, mostly for local companies. (Romero also directed a few shorts for local children’s TV host Fred Rogers, including the immortal Mister Rogers Gets a Tonsillectomy, and branched out a few times into more national concerns, including a high-profile campaign film for Lenore Romney’s unsuccessful 1970 Senate run—any footage you saw of young Mitt during his presidential run was likely filmed by Romero.) Ads were a way to pay the bills and buy cameras and lights and such; shooting them was also the closest thing to film school Romero’s crew could find in Pittsburgh. They made rent while teaching themselves the equipment, developing their style, and making the sort of connections that would be useful in raising money for low-budget features. But by 1973 Romero was past that. All through his tenure as a commercial director he had been trying to get features off the ground, and with Night, he’d finally succeeded. He wasn’t above this sort of work for hire, but he’d done enough of it for a lifetime.

In 1973, only five years after releasing Night of the Living Dead, George A. Romero was, in the eyes of the movie industry, washed up. Night was already well on its way from revolting little horror movie to hipster favorite to cult classic to actual classic. But no one saw much money from it—even though, it should be pointed out, it was still playing on the Midnight Movie circuit in 1973. And after failing to replicate Night’s success with subsequent efforts, Romero’s filmmaking troupe split, burdened by debts and frustrated by the mounting difficulties of raising money for another movie.

Romero was on his own for the first time in his career. He was in Pittsburgh, about as far as you can get from Hollywood, and he wanted to work. He wanted to keep making movies. He and his collaborators had built a very successful business making commercials, mostly for local companies. (Romero also directed a few shorts for local children’s TV host Fred Rogers, including the immortal Mister Rogers Gets a Tonsillectomy, and branched out a few times into more national concerns, including a high-profile campaign film for Lenore Romney’s unsuccessful 1970 Senate run—any footage you saw of young Mitt during his presidential run was likely filmed by Romero.) Ads were a way to pay the bills and buy cameras and lights and such; shooting them was also the closest thing to film school Romero’s crew could find in Pittsburgh. They made rent while teaching themselves the equipment, developing their style, and making the sort of connections that would be useful in raising money for low-budget features. But by 1973 Romero was past that. All through his tenure as a commercial director he had been trying to get features off the ground, and with Night, he’d finally succeeded. He wasn’t above this sort of work for hire, but he’d done enough of it for a lifetime.

No comments:

Post a Comment