Rising seas and a great southern star: Aboriginal oral traditions stretch back more than 12,000 years

How long do you think stories can be passed down, generation to generation?

Hundreds of years? Thousands?

Today, we publish new research in the Journal of Archaeological Science demonstrating that traditional stories from Tasmania have been passed down for more than 12,000 years. And we use multiple lines of evidence to show it.

Tasmania's violent colonial history

Within months of establishing a colonial outpost on the island in 1803, British officials had committed several acts of genocide against Aboriginal Tasmanian (Palawa) people. By the mid-1820s, soldiers, convicts, and free settlers had taken up arms to fight what became known as the "Black War", aimed at capturing or killing Palawa and dispossessing them of their Country.

Tasmania's colonial government appointed George Augustus Robinson to "conciliate" with the Palawa. From 1829 to 1835, Robinson traveled with a small group of Palawa, including Trukanini and her husband, Wurati. By 1832, Robinson's "friendly mission" had turned to forced removals.

Robinson kept a daily journal, which included records of Palawa languages and traditions. Over time, Palawa men and women slowly began to share some of their knowledge, explaining how their ancestors came to Tasmania (Lutruwita) by land from the far north, before the sea formed and turned their home into an island. They also spoke about the Sun-man, the Moon-woman, and a bright southern star.

These stories are of immense importance to today's Palawa families who survived the devastating impact of colonization, and who continue to share these unique creation stories. Through careful investigation of colonial records, and collaborating with Palawa knowledge-holders, we found something remarkable.

Rising seas and the formation of Lutruwita

Over the past 65,000 years, Australia's First Peoples witnessed natural disasters and significant changes to the land, sea and sky. Volcanoes spewed fire, earthquakes shook the land, tsunamis inundated the coastlines, droughts plagued the continent, meteorites fell to the earth, and the stars shifted in the night sky.

Some 20,000 years ago, the world was in the grip of an ice age. Australia was conspicuously drier than it is today, and the ocean was significantly lower. All of that sea water was bound up in glaciers that swathed vast tracts of land, particularly across the Northern Hemisphere, and polar ice caps much larger than ours today.

As time passed, temperatures gradually rose and the ice began to melt. After 10,000 years, the sea level had risen 125 meters; a process that dramatically transformed coastlines and submerged landscapes that had been ancestral Country for thousands of generations. This forced humans to change where and how they lived.

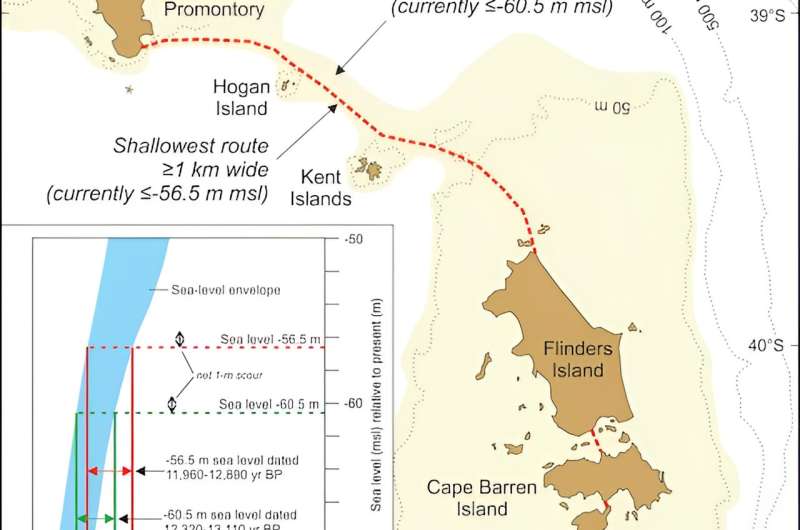

During the ice age, both Lutruwita and Papua New Guinea were connected to mainland Australia by dry land, forming a landmass called Sahul. As the seas rose, Tasmania's connection gradually narrowed to form what geologists call the Bassian Land Bridge.

People continued to live on this "land bridge", but by 12,700 years ago it had narrowed to just 5 kilometers wide (lime-green shading on the map above). Habitable land was gradually reduced as the sea closed in. Less than 300 years later, the "land bridge" was gone and Lutruwita was completely surrounded by water.

Palawa traditions from that time survived hundreds of generations of retelling, forming part of a larger canon of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stories around Australia. They described rising seas and submerging coastlines as the ice sheets melted before leveling off around 7,000 years ago. Stories of similar antiquity are known from other parts of the world.

A great south star

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures developed rich and complex knowledge systems about the stars, which are still used today. They describe the movements of the Sun, Moon, and stars, as well as rare cosmic events, such as eclipses, supernovae, and meteorite impacts.

In the 1830s, a Palawa Elder spoke about a time when the star Moinee was near the south celestial pole. He laid down a pair of spears in the sand and drew a few reference stars to triangulate its position.

Colonists seemed perplexed about the presence of an antipodean counterpart to Polaris, as no southern pole star exists today. Some tried to identify the stars on the star map, but seemed confused and labeled them incorrectly, as they were unaware of an important astronomical process called axial precession.

As the Earth rotates, it wobbles on its axis like a spinning top. This shifts the location of the celestial poles, tracing out a large circle every 26,000 years. As thousands of years pass by, the positions of the stars in the sky slowly change.

Long ago, Canopus was at its southernmost point in the sky. Lying just over 10 degrees from the south celestial pole, it appeared to always hover in the southern skies each night. That last occurred 14,000 years ago, before rising seas turned Lutruwita into an island.

Exciting collaborative futures

We can see through independent lines of evidence that Palawa stories have been passed down for more than twelve millennia. We also find here the only example in the world of an oral tradition describing a star's position as it would have appeared in the sky over 10,000 years ago.

Our investigation of colonial records that record traditional systems of knowledge has demonstrated a powerful cross-cultural way of better understanding deep human history. This also recognizes the immense value of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander traditions today.

More information: Duane Hamacher et al, The archaeology of orality: Dating Tasmanian Aboriginal oral traditions to the Late Pleistocene, Journal of Archaeological Science (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2023.105819

Journal information: Journal of Archaeological Science

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]() Evidence the oral stories of Australia's First Nations might be 10,000 years old

Evidence the oral stories of Australia's First Nations might be 10,000 years old

James Churchward - Wikipedia

Churchward was born in Bridestow, Okehampton, Devon at Stone House to Henry and Matilda (née Gould) Churchward. James had four brothers and four sisters. In November 1854, Henry died and the family moved in with Matilda's parents in the hamlet of Kigbear, near Okehampton. Census records indicate the family next moved to London when James was 18 after his grandfather George Gould died.

THE SACRED SYMBOLS OF MU - James Churchward

COLONEL JAMES CHURCHWARD AUTHOR OF "THE LOST CONTINENT OF MU" "THE CHILDREN OF MU" ILLUSTRATED IVES WASHBURN; NEW YORK Scanned at sacred-texts.com, December, 2003.

3 Beards Podcast: Is the Lost Continent of Mu Real?

Author Jack Churchward joins the show to talk about his books that cover The Lost Continent of Mu, a subject brought to life by the works of his great grandfather Col. James Churchward.

Lifting the Veil on the Lost Continent of Mu: The Motherland of Men

The Stone Tablets of Mu

Crossing the Sands of Time

are books Jack Churchward has penned to cover the works of his great grandfather and bring into focus on what is fact and what is fiction.

The mythical idea of the “Land of Mu” first appeared in the works of the British-American antiquarian Augustus Le Plongeon (1825–1908), after his investigations of the Maya ruins in Yucatán. He claimed that he had translated the first copies of the Popol Vuh, the sacred book of the K’iche’ from the ancient Mayan using Spanish. He claimed the civilization of Yucatán was older than those of Greece and Egypt, and told the story of an even older continent.

Col. James Churchward claimed that the landmass of Mu was located in the Pacific Ocean, and stretched east–west from the Marianas to Easter Island, and north–south from Hawaii to Mangaia. According to Churchward the continent was supposedly 5,000 miles from east to west and over 3,000 miles from north to south, which is larger than South America. The continent was believed to be flat with massive plains, vast rivers, rolling hills, large bays, and estuaries. He claimed that according to the creation myth he read in the Indian tablets, Mu had been lifted above sea level by the expansion of underground volcanic gases. Eventually Mu “was completely obliterated in almost a single night” after a series of earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, “the broken land fell into that great abyss of fire” and was covered by “fifty millions of square miles of water.” Churchward claimed the reasoning for the continent’s destruction in one night was because the main mineral on the island was granite and was honeycombed to create huge shallow chambers and cavities filled with highly explosive gases. Once the chambers were empty after the explosion, they collapsed on themselves, causing the island to crumble and sink.

No comments:

Post a Comment