Neil McCormick

Sun, 18 February 2024

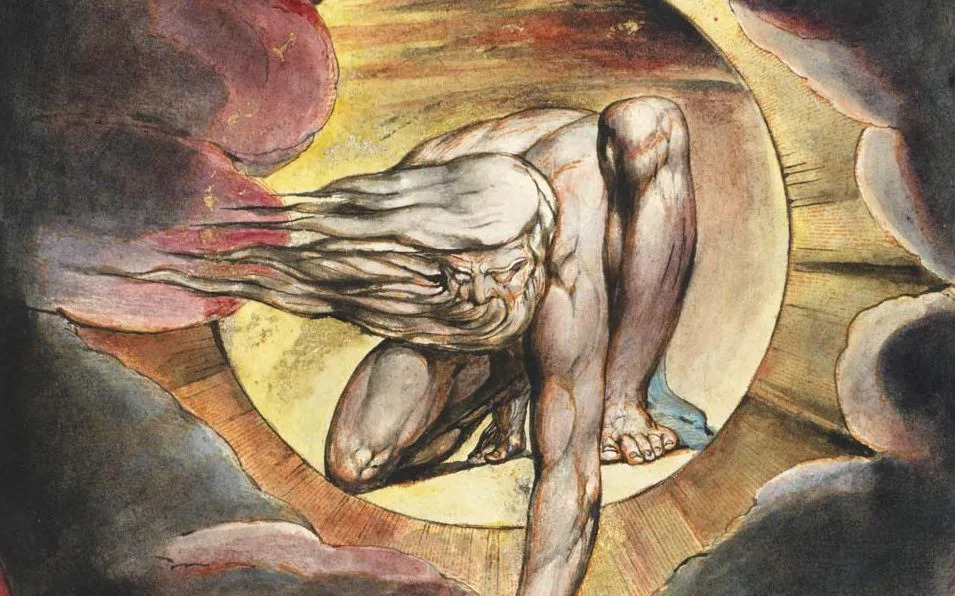

‘He gives hope to unappreciated artists’: detail from The Ancient of Days - Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

William Blake is today exalted as one of the greatest British artists. His life mask is in the National Portrait Gallery, while a bust sits in Westminster Abbey. His poem “The Tyger” is among the most anthologised in the English language, grappling with creation in terms that even children can grasp: “What immortal hand or eye / Could frame thy fearful symmetry?” Another, “And did those feet in ancient time”, later made into the hymn Jerusalem, has become the unofficial national anthem, sung at rugby matches, political party conferences and the Last Night of the Proms – which adds to the perception of Blake as an establishment man.

This week, William Blake’s Universe opens at Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum, in which you will find such familiar pictures as Blake’s The Ancient of Days and the illustrations to his “prophetic book” Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion. But you can also spot these images – or recreations – in the unlikeliest of places: a recent video by the Iron Maiden frontman Bruce Dickinson, Rain on the Graves, opens with a quote from Blake (“A Truth that’s told with bad intent / Beats all the Lies you can invent”) and ends with the heavy-metal singer clawing over Blake’s gravestone.

“The thing about Blake is that he appears unexpectedly,” observes John Higgs, the author of William Blake vs the World. “He comes to us in memes, horror films, video games and pop songs. These are not respectable routes for information. You fall off the tracks and Blake is there, waiting to be discovered.”

Blake’s posthumous reputation would have astonished the man himself, who “spent his life impoverished and misunderstood”, as Higgs points out. Born to shopkeepers in London in 1757, Blake never went to school, eked out a living as a printer and, in 1827, was buried in an unmarked grave.

“Blake was not a little Englander,” notes David Bindman, co-curator of the Fitzwilliam exhibition. “He was part of a new European consciousness, the dawn of modernism – doesn’t like governments or churches, fascinated by the French Revolution and American Revolution, quite a fervent religious person, but nonconformist.” Blake was anti-slavery, pro-sexual freedom and women’s rights. “You can see his attraction to rock musicians and the counterculture. He’s a philosopher and mythologist, whose work comes out of a tremendous psychodrama.”

Albion’s Angel rose, 1794 - © The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

Bindman considers Jerusalem to be a “misunderstood poem about the building of a spiritual realm. Blake’s radical ideas encompassed a vision of the whole world as potentially in political and spiritual revolution” to which his attitude was essentially “apocalyptic”, believing “the destruction of the material world would be a cleansing act”. You don’t get much of that at the Last Night of the Proms.

Mark E Smith’s post-punk agitators the Fall recorded their own savage take on Jerusalem in 1988, its anti-government spin more in tune with Blake’s intent. And Blake’s influence cascades through rock, with references abounding in songs by Bob Dylan (Every Grain of Sand), the Doors (End of the Night), Led Zeppelin (Achilles Last Stand), Tangerine Dream (Tyger), the Verve (History), Pet Shop Boys (Inside a Dream), and the Libertines (Pete Doherty’s visions of Albion).

Donovan, Van Morrison and Nick Cave have all demonstrated a Blakeian fascination with the power of imagination as a path to truth. Blake wrote in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell that, “If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.” It gave the Doors their name, whilst another Blake aphorism gave Jim Morrison his essential mythos: “The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.” (That didn’t end well for Morrison.)

Patti Smith is devoted to Blake, and edited a selection of his writings, published in 2007. She exulted in her introduction how Blake “did not jealously guard his vision; he shared it through his work and called upon us to animate the creative spirit within us”. And it was Blake’s devotion to his art that gave Kris Kristofferson – who studied the Romantic poets at Oxford – the courage to turn his back on a military career and take a job as a janitor in a Nashville recording studio.

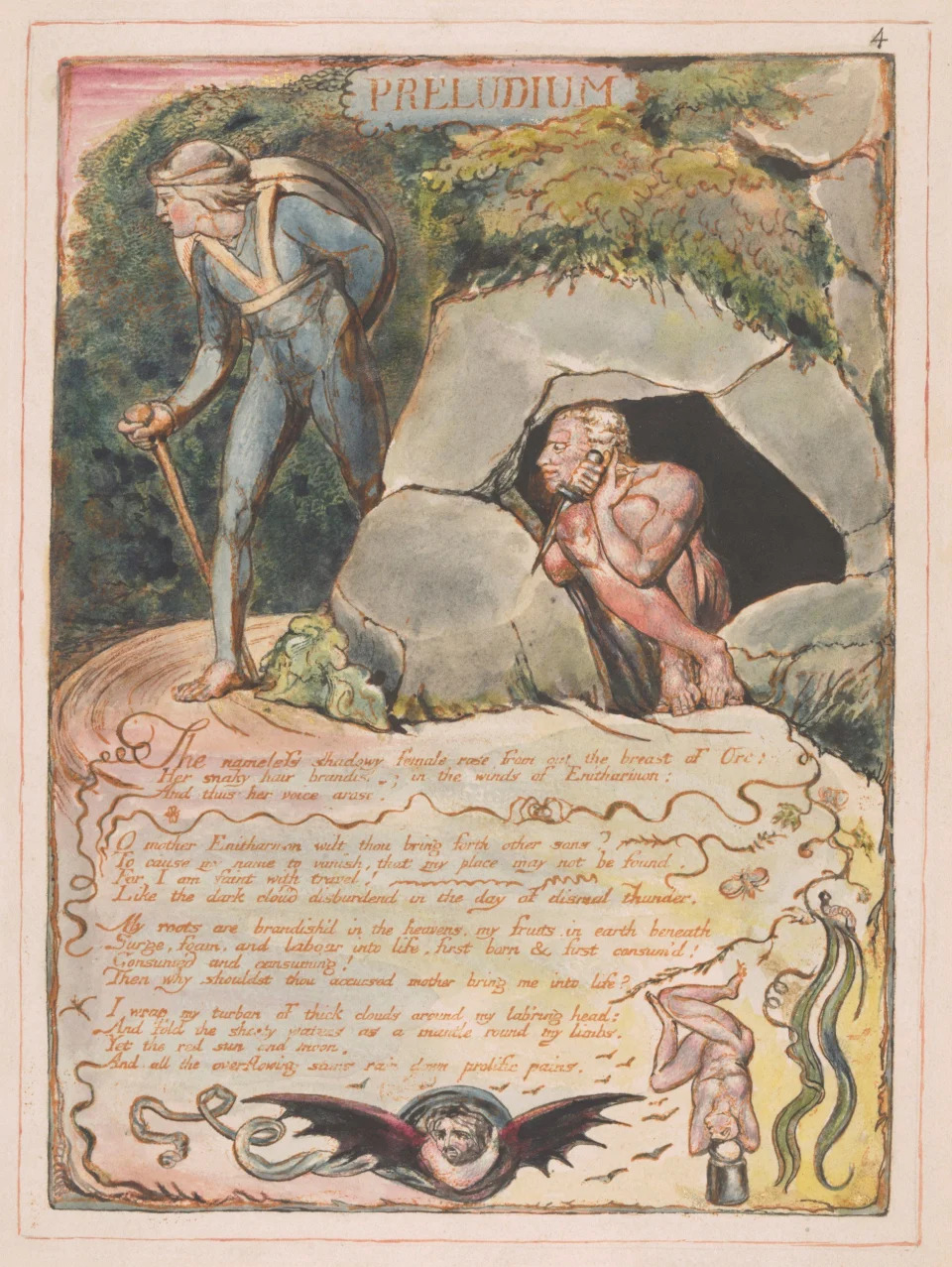

In the 20th century, Blake entered the counterculture through Aldous Huxley, whose 1954 work on the transformative power of mescaline was titled The Doors of Perception, and thence via the experimental writer William Burroughs who introduced Blake to Allen Ginsberg (the latter, at the age of 22, was masturbating while reading Blake’s poetry when he experienced a hallucination of Blake speaking to him). Ginsberg’s influence on Bob Dylan helped feed Blake into rock culture.

“There’s so much in Blake that was speaking to the postwar generation, about sexual liberation, freeing yourself from the ‘mind-forg’d manacles’, it was all very psychedelic and anti-authoritarian,” notes Higgs. “So many people were convinced that he must have been on drugs to have all these visions, which is almost certainly not the case, but Blake was really invested in the idea that imagination is the divine quality of the universe.”

U2 are so in thrall to Blake that they named two albums in his honour, Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience. Musicians are attracted to Blake “because he believed in the invisible realm and wanted to make it visible”, explains Bono. “That’s the call of so many artists in so many different mediums, to bring the inside to the outside, the unseen into the seen… to see heaven in a guitar riff and hold infinity in a bass line, to find eternity in a rock and roll show!”

The singer-songwriter Frank Turner composed one of the most beautiful songs about the artist, I Believed You, William Blake, questioning artistic conviction from the perspective of Blake’s wife, Catherine. “She is one of these neglected female historical figures, who had a fair amount to do with his artistic output and may have been the only person who ever had a handle on the true totality of his theology,” enthuses Turner. “Part of the reason why Blake remains so resonant is he’s so titanically weird, and impossible to pin down. You can get very lost in his poetry, in good and bad ways. A lot of it is pretty impenetrable but his imagery is extremely striking. He was a man out of time, and not successful in his own time. Yet he has achieved immortality, or longevity, at least. He still matters.”

‘So many thought he must have been on drugs to have all these visions’: Blake's Preludium in Europe a Prophecy, 1794 - © The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

The punk DIY spirit of Blake’s career adds to his appeal. Blake had his own printing press, put out his own hand-coloured books and staged his own exhibitions, despite a complete lack of commercial success (he only sold about 30 copies of Songs of Innocence and of Experience). “He’s doing all the artwork, he’s staging the show, and no one cared at all,” notes Turner. “As an indie artist, there’s painful echoes. Maybe that’s Blake’s endless fascination, he gives hope to misunderstood artists the world over that, in several hundred years, they’ll be the most famous artist of that era.”

Patti Smith’s 2004 song My Blakean Year addresses the struggles of an unrecognised artist. “I felt sorry for myself. And then I thought of Blake,” according to Smith. “His work never sold. He lived in poverty. When he spoke out, he nearly lost his life. What I learnt from William Blake is, don’t give up. And don’t expect anything. If you perceive that you have a gift, you already have life.”

William Blake’s Universe is at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk), from Friday to May 19

No comments:

Post a Comment