SPACE

Dark matter: our new experiment aims to turn the ghostly substance into actual light

The Conversation

May 2, 2024

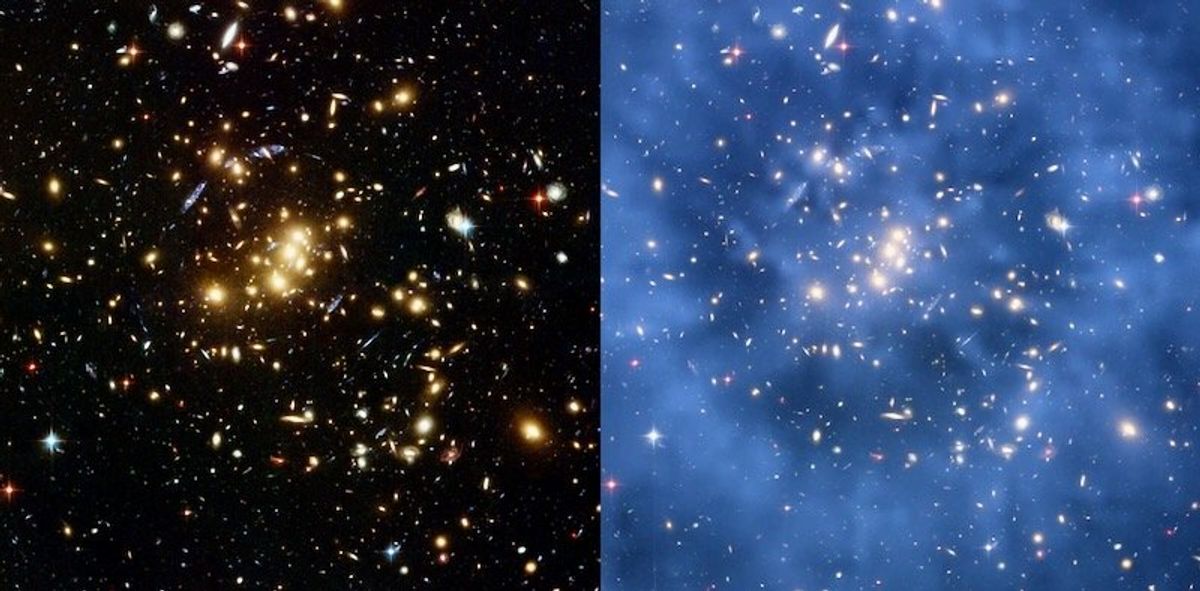

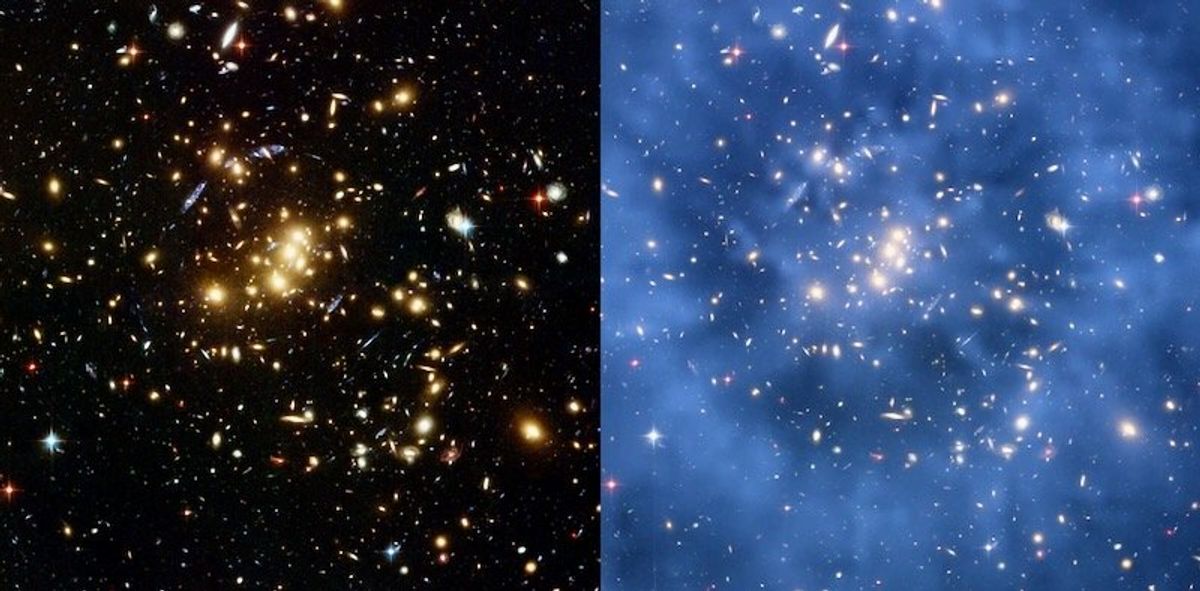

Galaxy cluster, left, with ring of dark matter visible, right. NASA

A ghost is haunting our universe. This has been known in astronomy and cosmology for decades. Observations suggest that about 85% of all the matter in the universe is mysterious and invisible. These two qualities are reflected in its name: dark matter.

Several experiments have aimed to unveil what it’s made of, but despite decades of searching, scientists have come up short. Now our new experiment, under construction at Yale University in the US, is offering a new tactic.

Dark matter has been around the universe since the beginning of time, pulling stars and galaxies together. Invisible and subtle, it doesn’t seem to interact with light or any other kind of matter. In fact, it has to be something completely new.

The standard model of particle physics is incomplete, and this is a problem. We have to look for new fundamental particles. Surprisingly, the same flaws of the standard model give precious hints on where they may hide.

The trouble with the neutron

Let’s take the neutron, for instance. It makes up the atomic nucleus along with the proton. Despite being neutral overall, the theory states that it it made up of three charged constituent particles called quarks. Because of this, we would expect some parts of the neutron to be charged positively and others negatively –this would mean it was having what physicist call an electric dipole moment.

Yet, many attempts to measure it have come with the same outcome: it is too small to be detected. Another ghost. And we are not talking about instrumental inadequacies, but a parameter that has to be smaller than one part in ten billion. It is so tiny that people wonder if it could be zero altogether.

In physics, however, the mathematical zero is always a strong statement. In the late 70s, particle physicistsnRoberto Peccei and Helen Quinn (and later, Frank Wilczek and Steven Weinberg) tried to accommodate theory and evidence.

They suggested that, maybe, the parameter is not zero. Rather it is a dynamical quantity that slowly lost its charge, evolving to zero, after the Big Bang. Theoretical calculations show that, if such an event happened, it must have left behind a multitude of light, sneaky particles.

These were dubbed “axions” after a detergent brand because they could “clear up” the neutron problem. And even more. If axions were created in the early universe, they have been hanging around since then. Most importantly, their properties check all the boxes expected for dark matter. For these reasons, axions have become one of the favourite candidate particles for dark matter.

Axions would only interact with other particles weakly. However, this means they would still interact a bit. The invisible axions could even transform into ordinary particles, including – ironically – photons, the very essence of light. This may happen in particular circumstances, like in the presence of a magnetic field. This is a godsend for experimental physicists.

Experimental design

Many experiments are trying to evoke the axion-ghost in the controlled environment of a lab. Some aim to convert light into axions, for instance, and then axions back into light on the other side of a wall.

At present, the most sensitive approach targets the halo of dark matter permeating the galaxy (and consequently, Earth) with a device called a haloscope. It is a conductive cavity immersed in a strong magnetic field; the former captures the dark matter surrounding us (assuming it is axions), while the latter induces the conversion into light. The result is an electromagnetic signal appearing inside the cavity, oscillating with a characteristic frequency depending on the axion mass.

The system works like a receiving radio. It needs to be properly adjusted to intercept the frequency we are interested in. Practically, the dimensions of the cavity are changed to accommodate different characteristic frequencies. If the frequencies of the axion and the cavity do not match, it is just like tuning a radio on the wrong channel.

The powerful magnet is moved to the lab at Yale.

The Conversation

May 2, 2024

Galaxy cluster, left, with ring of dark matter visible, right. NASA

A ghost is haunting our universe. This has been known in astronomy and cosmology for decades. Observations suggest that about 85% of all the matter in the universe is mysterious and invisible. These two qualities are reflected in its name: dark matter.

Several experiments have aimed to unveil what it’s made of, but despite decades of searching, scientists have come up short. Now our new experiment, under construction at Yale University in the US, is offering a new tactic.

Dark matter has been around the universe since the beginning of time, pulling stars and galaxies together. Invisible and subtle, it doesn’t seem to interact with light or any other kind of matter. In fact, it has to be something completely new.

The standard model of particle physics is incomplete, and this is a problem. We have to look for new fundamental particles. Surprisingly, the same flaws of the standard model give precious hints on where they may hide.

The trouble with the neutron

Let’s take the neutron, for instance. It makes up the atomic nucleus along with the proton. Despite being neutral overall, the theory states that it it made up of three charged constituent particles called quarks. Because of this, we would expect some parts of the neutron to be charged positively and others negatively –this would mean it was having what physicist call an electric dipole moment.

Yet, many attempts to measure it have come with the same outcome: it is too small to be detected. Another ghost. And we are not talking about instrumental inadequacies, but a parameter that has to be smaller than one part in ten billion. It is so tiny that people wonder if it could be zero altogether.

In physics, however, the mathematical zero is always a strong statement. In the late 70s, particle physicistsnRoberto Peccei and Helen Quinn (and later, Frank Wilczek and Steven Weinberg) tried to accommodate theory and evidence.

They suggested that, maybe, the parameter is not zero. Rather it is a dynamical quantity that slowly lost its charge, evolving to zero, after the Big Bang. Theoretical calculations show that, if such an event happened, it must have left behind a multitude of light, sneaky particles.

These were dubbed “axions” after a detergent brand because they could “clear up” the neutron problem. And even more. If axions were created in the early universe, they have been hanging around since then. Most importantly, their properties check all the boxes expected for dark matter. For these reasons, axions have become one of the favourite candidate particles for dark matter.

Axions would only interact with other particles weakly. However, this means they would still interact a bit. The invisible axions could even transform into ordinary particles, including – ironically – photons, the very essence of light. This may happen in particular circumstances, like in the presence of a magnetic field. This is a godsend for experimental physicists.

Experimental design

Many experiments are trying to evoke the axion-ghost in the controlled environment of a lab. Some aim to convert light into axions, for instance, and then axions back into light on the other side of a wall.

At present, the most sensitive approach targets the halo of dark matter permeating the galaxy (and consequently, Earth) with a device called a haloscope. It is a conductive cavity immersed in a strong magnetic field; the former captures the dark matter surrounding us (assuming it is axions), while the latter induces the conversion into light. The result is an electromagnetic signal appearing inside the cavity, oscillating with a characteristic frequency depending on the axion mass.

The system works like a receiving radio. It needs to be properly adjusted to intercept the frequency we are interested in. Practically, the dimensions of the cavity are changed to accommodate different characteristic frequencies. If the frequencies of the axion and the cavity do not match, it is just like tuning a radio on the wrong channel.

The powerful magnet is moved to the lab at Yale.

Yale University, CC BY-SA

Unfortunately, the channel we are looking for cannot be predicted in advance. We have no choice but to scan all the potential frequencies. It is like picking a radio station in a sea of white noise – a needle in a haystack – with an old radio that needs to be bigger or smaller every time we turn the frequency knob.

Yet, those are not the only challenges. Cosmology points to tens of gigahertz as the latest, promising frontier for axion search. As higher frequencies require smaller cavities, exploring that region would require cavities too small to capture a meaningful amount of signal.

New experiments are trying to find alternative paths. Our Axion Longitudinal Plasma Haloscope (Alpha) experiment uses a new concept of cavity based on metamaterials.

Metamaterials are composite materials with global properties that differ from their constituents – they are more than the sum of their parts. A cavity filled with conductive rods gets a characteristic frequency as if it were one million times smaller, while barely changing its volume. That is exactly what we need. Plus, the rods provide a built-in, easy-adjustable tuning system.

We are currently building the setup, which will be ready to take data in a few years. The technology is promising. Its development is the result of the collaboration among solid-state physicists, electrical engineers, particle physicists and even mathematicians.

Despite being so elusive, axions are fuelling progress that no ghost will ever take away.

Andrea Gallo Rosso, Postdoctoral Fellow of Physics, Stockholm University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Unfortunately, the channel we are looking for cannot be predicted in advance. We have no choice but to scan all the potential frequencies. It is like picking a radio station in a sea of white noise – a needle in a haystack – with an old radio that needs to be bigger or smaller every time we turn the frequency knob.

Yet, those are not the only challenges. Cosmology points to tens of gigahertz as the latest, promising frontier for axion search. As higher frequencies require smaller cavities, exploring that region would require cavities too small to capture a meaningful amount of signal.

New experiments are trying to find alternative paths. Our Axion Longitudinal Plasma Haloscope (Alpha) experiment uses a new concept of cavity based on metamaterials.

Metamaterials are composite materials with global properties that differ from their constituents – they are more than the sum of their parts. A cavity filled with conductive rods gets a characteristic frequency as if it were one million times smaller, while barely changing its volume. That is exactly what we need. Plus, the rods provide a built-in, easy-adjustable tuning system.

We are currently building the setup, which will be ready to take data in a few years. The technology is promising. Its development is the result of the collaboration among solid-state physicists, electrical engineers, particle physicists and even mathematicians.

Despite being so elusive, axions are fuelling progress that no ghost will ever take away.

Andrea Gallo Rosso, Postdoctoral Fellow of Physics, Stockholm University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

‘We’re in a new era’: the 21st-century space race takes off

As humans enter what has been termed the ‘third space age’, it’s private companies – not governments – leading the charge

Oliver Holmes

As humans enter what has been termed the ‘third space age’, it’s private companies – not governments – leading the charge

Oliver Holmes

THE GUARDIAN

Fri 3 May 2024

If the 20th-century space race was about political power, this century’s will be about money. But for those who dream of sending humans back to the moon and possibly Mars, it’s an exciting time to be alive whether it’s presidents or billionaires paying the fare.

Space flight is having a renaissance moment, bringing a fresh energy not seen since the days of the Apollo programme and, for the first time, with private companies rather than governments leading the charge.

A series of recent milestone missions, not least the increasingly successful test flights of the largest rocket ever made and the first privately built probe to land on the lunar surface, have embedded a growing idea that humans are entering what has been termed the “third space age”.

“To say we’re in a new era, that’s absolutely fair,” said Greg Sadlier, a space economist and the co-founder of the know.space consultancy. “We’re in the era of competition, or the commercial era. The barriers to entry are lower, the costs have fallen, which has opened the doors to a much larger pool of nations,” he said. “It’s the democratisation of space, if you like.”

Today, more than 70 countries have space programmes, but for a long time, the US and the Soviet Union were the only big players.

Humanity’s first space explorer, the Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, orbited around the globe in April 1961. A year later, US President John F Kennedy gave his famous “we choose to go to the moon” speech, promising to get an American man on the lunar surface by the end of the decade ahead of a “hostile flag of conquest”.

Fri 3 May 2024

If the 20th-century space race was about political power, this century’s will be about money. But for those who dream of sending humans back to the moon and possibly Mars, it’s an exciting time to be alive whether it’s presidents or billionaires paying the fare.

Space flight is having a renaissance moment, bringing a fresh energy not seen since the days of the Apollo programme and, for the first time, with private companies rather than governments leading the charge.

A series of recent milestone missions, not least the increasingly successful test flights of the largest rocket ever made and the first privately built probe to land on the lunar surface, have embedded a growing idea that humans are entering what has been termed the “third space age”.

“To say we’re in a new era, that’s absolutely fair,” said Greg Sadlier, a space economist and the co-founder of the know.space consultancy. “We’re in the era of competition, or the commercial era. The barriers to entry are lower, the costs have fallen, which has opened the doors to a much larger pool of nations,” he said. “It’s the democratisation of space, if you like.”

Today, more than 70 countries have space programmes, but for a long time, the US and the Soviet Union were the only big players.

Humanity’s first space explorer, the Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, orbited around the globe in April 1961. A year later, US President John F Kennedy gave his famous “we choose to go to the moon” speech, promising to get an American man on the lunar surface by the end of the decade ahead of a “hostile flag of conquest”.

A mural of Yuri Gagarin in Krasnogorsk, outside Moscow.

Photograph: Maxim Shipenkov/EPA

“To be sure, all this costs us all a good deal of money,” Kennedy acknowledged, but the cold war motivated him to spend the modern-day equivalent of hundreds of billions in US taxpayers’ money to win the space race.

The end of the cold war in 1989 brought a brief moment of global optimism, leading to the second, more collaborative space age. The International Space Station was assembled over 13 years and, since 2000, people of multiple nationalities have been living in space constantly, working together on experiments in the orbiting laboratory.

However, this second era also saw a dip in efforts to get humans farther out into space, symbolised by Nasa’s space shuttle programme that never sent people beyond Earth’s orbit and was eventually disbanded in 2011, in large part because the US government did not want to keep bankrolling its high costs. Afterwards, Washington had to rely on Moscow’s Soyuz rockets to get its astronauts into space.

“To be sure, all this costs us all a good deal of money,” Kennedy acknowledged, but the cold war motivated him to spend the modern-day equivalent of hundreds of billions in US taxpayers’ money to win the space race.

The end of the cold war in 1989 brought a brief moment of global optimism, leading to the second, more collaborative space age. The International Space Station was assembled over 13 years and, since 2000, people of multiple nationalities have been living in space constantly, working together on experiments in the orbiting laboratory.

However, this second era also saw a dip in efforts to get humans farther out into space, symbolised by Nasa’s space shuttle programme that never sent people beyond Earth’s orbit and was eventually disbanded in 2011, in large part because the US government did not want to keep bankrolling its high costs. Afterwards, Washington had to rely on Moscow’s Soyuz rockets to get its astronauts into space.

SpaceX’s Starship rocket stands at its Texas launch pad.

Photograph: AP

Yet those high costs have now been driven down by private businesses entering the scene, often as government contractors. In the past few years, some of these businesses have started to make money, although not from headline-grabbing reasons such as space tourism but mostly for sending up communication satellites, especially broadband internet. Many estimates suggest the global space industry could generate revenues of more than $1tn within the next two decades.

In an article published last year by the influential strategy and management consultancy McKinsey & Company, global managing partner Bob Sternfels and his colleagues wrote to CEOs: “If space isn’t part of your strategy, it needs to be.”

They added: “Only recently have we seen significant acceleration down the cost curve: launch costs have fallen 95% (with another massive reduction expected in the coming years) thanks to reuse, improved engineering, and increased volumes.”

Elon Musk’s SpaceX has been at the forefront of this movement, launching 96 times last year with its reusable rockets. The company’s largest system, called Starship and still in development, has been marketed as an interplanetary explorer. Musk says he built the 120-metre rocket so that humans can colonise Mars. Before then, Nasa has contracted SpaceX to land astronauts, including the first woman, on the moon this decade.

As a business venture, it could make money well before then by serving as the equivalent of a flying cargo ship. Starship has a payload of up to 150 metric tonnes, five times the load the space shuttle could carry.

Global politics continues to play a role in space but with more players. China has overtaken Russia as the main national contender to the US, with its own space station in operation, probes on the moon and a rover on Mars. On Friday, Beijing is due to launch a robotic spacecraft to the moon’s far side.

The moon’s south pole, in particular, is seen as a “golden belt” for lunar exploration as it contains water ice, which could be used as drinking water and even broken down to make rocket fuel.

Scientists are nervous about both the politicisation and the commercialisation of space, especially with talk of future “mining” operations on the pristine, untouched moon. Advocates of space exploration, however, point to advancements made so far. The CT scan, a critical medical device that can identify tumours, traces its origins to pre-Apollo mission research; astronauts on the space station have been using the unique microgravity environment to better understand diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

For economists like Sadlier, the third space age creates an unprecedented situation – one that could upend the very foundations of the market system. “In economics, we assume that resources are limited; land is limited; natural resources are limited,” he said. “With space, it allows us to change that.”

Yet those high costs have now been driven down by private businesses entering the scene, often as government contractors. In the past few years, some of these businesses have started to make money, although not from headline-grabbing reasons such as space tourism but mostly for sending up communication satellites, especially broadband internet. Many estimates suggest the global space industry could generate revenues of more than $1tn within the next two decades.

In an article published last year by the influential strategy and management consultancy McKinsey & Company, global managing partner Bob Sternfels and his colleagues wrote to CEOs: “If space isn’t part of your strategy, it needs to be.”

They added: “Only recently have we seen significant acceleration down the cost curve: launch costs have fallen 95% (with another massive reduction expected in the coming years) thanks to reuse, improved engineering, and increased volumes.”

Elon Musk’s SpaceX has been at the forefront of this movement, launching 96 times last year with its reusable rockets. The company’s largest system, called Starship and still in development, has been marketed as an interplanetary explorer. Musk says he built the 120-metre rocket so that humans can colonise Mars. Before then, Nasa has contracted SpaceX to land astronauts, including the first woman, on the moon this decade.

As a business venture, it could make money well before then by serving as the equivalent of a flying cargo ship. Starship has a payload of up to 150 metric tonnes, five times the load the space shuttle could carry.

Global politics continues to play a role in space but with more players. China has overtaken Russia as the main national contender to the US, with its own space station in operation, probes on the moon and a rover on Mars. On Friday, Beijing is due to launch a robotic spacecraft to the moon’s far side.

The moon’s south pole, in particular, is seen as a “golden belt” for lunar exploration as it contains water ice, which could be used as drinking water and even broken down to make rocket fuel.

Scientists are nervous about both the politicisation and the commercialisation of space, especially with talk of future “mining” operations on the pristine, untouched moon. Advocates of space exploration, however, point to advancements made so far. The CT scan, a critical medical device that can identify tumours, traces its origins to pre-Apollo mission research; astronauts on the space station have been using the unique microgravity environment to better understand diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

For economists like Sadlier, the third space age creates an unprecedented situation – one that could upend the very foundations of the market system. “In economics, we assume that resources are limited; land is limited; natural resources are limited,” he said. “With space, it allows us to change that.”

The new ‘space race’: what are China’s ambitions and why is the US so concerned?

As China launches its Chang’e-6 mission to the far side of the moon, US officials have expressed alarm at the pace of its advancements

China to launch ambitious moon mission

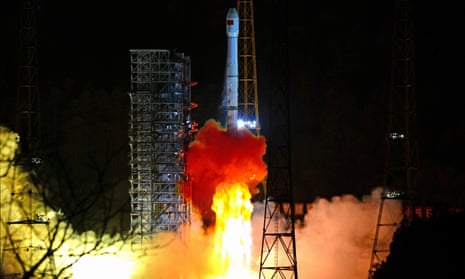

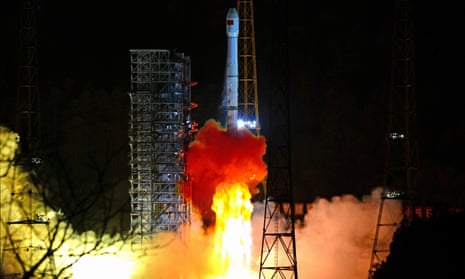

Long March-3B rocket carrying the Chang'e 4 lunar probe takes off. The US has expressed alarm at China’s ambitions in space.

Photograph: China Stringer Network/Reuters

Helen Davidson

Helen Davidson

in Taipei

Sun 5 May 2024

The worsening rivalry between the world’s two most powerful countries that has in recent years spread across the world, has now extended beyond the terrestrial, into the realms of the celestial.

As China has become deeply enmeshed in strategic competition with the US – while edging towards outright hostilities with other regional neighbours – Washington’s alarm at the pace of its advancement in space is growing ever-louder.

Beijing has made no secret over its ambitions and a spate of recent successful space missions has shown that the government’s rhetoric is backed by technological advances.

‘We’re in a space race’: Nasa sounds alarm at Chinese designs on moon

On Friday, China launched a robotic spacecraft on a round trip to the moon’s far side, in a technically demanding mission that will pave the way for an inaugural Chinese crewed landing and a base on the lunar south pole. The Chang’e-6 is aiming to bring back samples from the side of the moon that permanently faces away from Earth.

Earlier this week saw the launch of the Shenzhou-18, Beijing’s latest staffed spacecraft mission to the Tiangong space station, which was developed after China was excluded from the International Space Station.

Along with the three taikonauts, a live fish which has been dubbed “the fourth crew member”, was among the crew. The zebrafish is part of an experiment to test the viability of a large closed ecosystem, involving fish and algae, to help people live in space for long periods.

But the collection of moon samples and the viability of zebrafish are not the only focus for China’s space sector.

The pace of China’s ambitions has drawn concern from the government’s major rival, the US, over Beijing’s geopolitical intentions amid what the head of Nasa has called a new “space race”.

The worsening rivalry between the world’s two most powerful countries that has in recent years spread across the world, has now extended beyond the terrestrial, into the realms of the celestial.

As China has become deeply enmeshed in strategic competition with the US – while edging towards outright hostilities with other regional neighbours – Washington’s alarm at the pace of its advancement in space is growing ever-louder.

Beijing has made no secret over its ambitions and a spate of recent successful space missions has shown that the government’s rhetoric is backed by technological advances.

‘We’re in a space race’: Nasa sounds alarm at Chinese designs on moon

On Friday, China launched a robotic spacecraft on a round trip to the moon’s far side, in a technically demanding mission that will pave the way for an inaugural Chinese crewed landing and a base on the lunar south pole. The Chang’e-6 is aiming to bring back samples from the side of the moon that permanently faces away from Earth.

Earlier this week saw the launch of the Shenzhou-18, Beijing’s latest staffed spacecraft mission to the Tiangong space station, which was developed after China was excluded from the International Space Station.

Along with the three taikonauts, a live fish which has been dubbed “the fourth crew member”, was among the crew. The zebrafish is part of an experiment to test the viability of a large closed ecosystem, involving fish and algae, to help people live in space for long periods.

But the collection of moon samples and the viability of zebrafish are not the only focus for China’s space sector.

The pace of China’s ambitions has drawn concern from the government’s major rival, the US, over Beijing’s geopolitical intentions amid what the head of Nasa has called a new “space race”.

The combination of the Chang’e-6 lunar probe and the Long March-5 Y8 carrier rocket prepares to launch in the Hainan province of China.

Photograph: China News Service/Getty Images

Last week the head of Nasa, Bill Nelson, said the US and China were “in effect, in a race” to return to the moon, and he feared that China wanted to stake territorial claims.

“We believe that a lot of their so-called civilian space program is a military program,” he told US legislators.

There are concerns over China’s development of counter-space weapons, including missiles that can target satellites, and spacecraft that can pull satellites out of orbit.

“On a geopolitical level, China’s space ambitions raise questions about how it might leverage its space capabilities to further its regional and domestic political and military interests,” says Dr Svetla Ben-Itzhak, deputy director of Johns Hopkins University’s West Space Scholars Program.

Gen Stephen Whiting of the US Space Command, told reporters last week that China’s advances were “cause for concern”, noting it had tripled the number of spy satellites in orbit over the last six years.

‘It’s the wild, wild west’

The US and China are indeed in a race, says Prof Kazuto Suzuki, of the Graduate School of Public Policy at the University of Tokyo, but it’s not to simply set feet on the moon like during the cold war. Rather, it’s to find and control resources, like water.

“It’s a race for who has better technical capabilities. China is quickly catching up. The pace of Chinese technological development is the threatening element [to the US],” he says.

Suzuki says international agreements don’t allow for national appropriation of resources on the moon, but in reality “it’s the wild, wild west”.

“Generally speaking China wants to be first so they have the right to dominate and monopolise the resources. If you have the resources in your hand then you have a huge advantage in the future of space exploration.”

The US and China are leading the development of separate space station programs for the moon. The US-led Artemis program includes plans for a “Lunar Gateway”, a station orbiting the moon as a communication and accommodation hub for astronauts, and a scientific laboratory.

The Americans however, “are not so interested in owning the moon because they’ve been there”, Suzuki says.

Last week the head of Nasa, Bill Nelson, said the US and China were “in effect, in a race” to return to the moon, and he feared that China wanted to stake territorial claims.

“We believe that a lot of their so-called civilian space program is a military program,” he told US legislators.

There are concerns over China’s development of counter-space weapons, including missiles that can target satellites, and spacecraft that can pull satellites out of orbit.

“On a geopolitical level, China’s space ambitions raise questions about how it might leverage its space capabilities to further its regional and domestic political and military interests,” says Dr Svetla Ben-Itzhak, deputy director of Johns Hopkins University’s West Space Scholars Program.

Gen Stephen Whiting of the US Space Command, told reporters last week that China’s advances were “cause for concern”, noting it had tripled the number of spy satellites in orbit over the last six years.

‘It’s the wild, wild west’

The US and China are indeed in a race, says Prof Kazuto Suzuki, of the Graduate School of Public Policy at the University of Tokyo, but it’s not to simply set feet on the moon like during the cold war. Rather, it’s to find and control resources, like water.

“It’s a race for who has better technical capabilities. China is quickly catching up. The pace of Chinese technological development is the threatening element [to the US],” he says.

Suzuki says international agreements don’t allow for national appropriation of resources on the moon, but in reality “it’s the wild, wild west”.

“Generally speaking China wants to be first so they have the right to dominate and monopolise the resources. If you have the resources in your hand then you have a huge advantage in the future of space exploration.”

The US and China are leading the development of separate space station programs for the moon. The US-led Artemis program includes plans for a “Lunar Gateway”, a station orbiting the moon as a communication and accommodation hub for astronauts, and a scientific laboratory.

The Americans however, “are not so interested in owning the moon because they’ve been there”, Suzuki says.

Spectators gather to watch the launch of the Chang’e One lunar orbiter in 2007. Photograph: China Daily/Reuters

“They know it’s not really a habitable place, they are more interested in Mars. So for them the Lunar Gateway is sort of a gas station for the journey to Mars.” If the Artemis program can source water from the moon, it could be processed to create rocket fuel from the hydrogen and oxygen.

In contrast, China and Russia announced in 2021 joint plans to build a shared research station on the surface of the moon. The International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) would be open to any interested international parties they said. However the US would unlikely be among them given its poor relations with both China and Russia.

Suzuki says the China-Russia station “is supposed to serve like the research station in Antarctica”, which is within the rules of international space treaties. “But if it turns out to be a station to base their territorial claims, then that is against the rules.”

The US is gathering allies to ensure China doesn’t win the space race. Earlier this month, not long after China announced its intentions to land a person on the moon, US leader Joe Biden and his Japanese counterpart Fumio Kishida pledged to send a astronaut from Japan – China’s historical rival – to the moon on Nasa’s Artemis missions in 2028 and again in 2032.

But China is also gathering allies. It has partnerships or financial stakes in projects across the Middle East and Latin America, and around a dozen international members for its ILRS.

But Ben-Itzhak notes there are some overlapping memberships. Also “neither bloc has instituted exclusionary practices thus far, which is promising”.

Ben-Itzhak says the US and China are indeed engaged in a race, but the term doesn’t fully capture “the complex, nuanced dynamics currently unfolding in space, in terms of the diverse and increasing number of actors and initiatives, and no clear end goal in sight”.

“The real challenge in space is not just about reaching a specific milestone, like planting flags or collecting rocks; it is about establishing a sustainable, resilient presence in an incredibly challenging environment. This is a test against our own abilities.”

Additional research by Chi Hui Lin

“They know it’s not really a habitable place, they are more interested in Mars. So for them the Lunar Gateway is sort of a gas station for the journey to Mars.” If the Artemis program can source water from the moon, it could be processed to create rocket fuel from the hydrogen and oxygen.

In contrast, China and Russia announced in 2021 joint plans to build a shared research station on the surface of the moon. The International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) would be open to any interested international parties they said. However the US would unlikely be among them given its poor relations with both China and Russia.

Suzuki says the China-Russia station “is supposed to serve like the research station in Antarctica”, which is within the rules of international space treaties. “But if it turns out to be a station to base their territorial claims, then that is against the rules.”

The US is gathering allies to ensure China doesn’t win the space race. Earlier this month, not long after China announced its intentions to land a person on the moon, US leader Joe Biden and his Japanese counterpart Fumio Kishida pledged to send a astronaut from Japan – China’s historical rival – to the moon on Nasa’s Artemis missions in 2028 and again in 2032.

But China is also gathering allies. It has partnerships or financial stakes in projects across the Middle East and Latin America, and around a dozen international members for its ILRS.

But Ben-Itzhak notes there are some overlapping memberships. Also “neither bloc has instituted exclusionary practices thus far, which is promising”.

Ben-Itzhak says the US and China are indeed engaged in a race, but the term doesn’t fully capture “the complex, nuanced dynamics currently unfolding in space, in terms of the diverse and increasing number of actors and initiatives, and no clear end goal in sight”.

“The real challenge in space is not just about reaching a specific milestone, like planting flags or collecting rocks; it is about establishing a sustainable, resilient presence in an incredibly challenging environment. This is a test against our own abilities.”

Additional research by Chi Hui Lin

No comments:

Post a Comment