One hundred years after his death, a play tells the story of Franz Kafka

The perception most hold about the writer is far from the truth

How did a German-speaking Jewish lawyer from Prague end up with the linguistic accolade of an eponymous adjective listed in the dictionary, namely ‘Kafkaesque’, meaning “of, relating to, or suggestive of Franz Kafka or his writings and having a nightmarishly complex, bizarre, or illogical quality”.

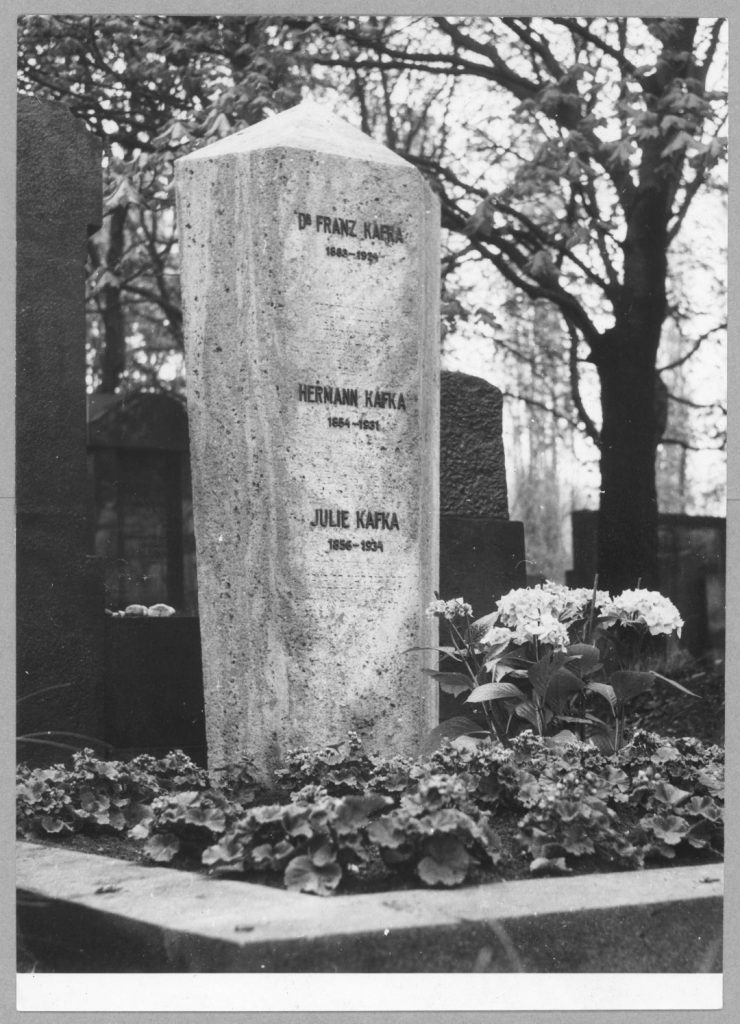

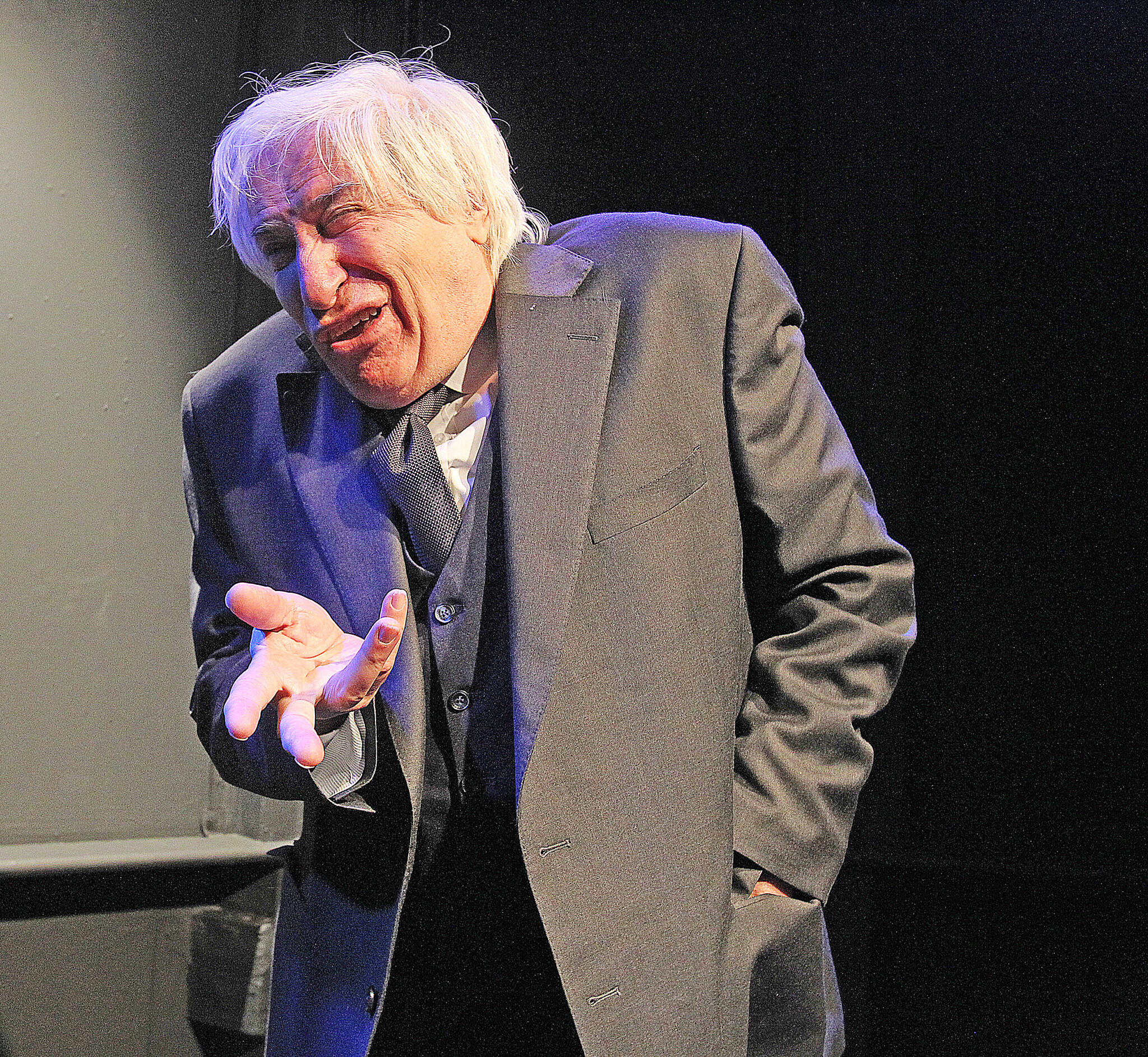

Kafka, born 3 July 1883 to Julie and Hermann, is the author of some remarkable works, notably The Metamorphosis, The Trial and The Castle. Many believe the man was as tortured as the characters he created. Jack Klaff, the writer and performer of the play Kafka, which is showing at Finborough Theatre, says that this perception is far from the truth.

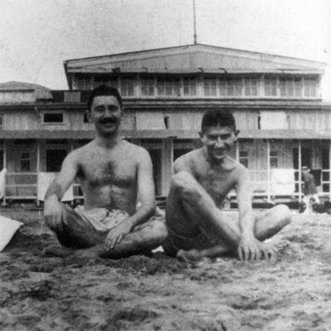

“Yes, Kafka had this prodigious talent, and he was an extraordinary person, but he wasn’t that much of a freak or weirdo. He was deeply sensitive, but we now know he could be gregarious – a popular, pretty regular guy. He came from an ordinary Jewish family, he had loves and passions just like most people do. And, at first, he followed a conventional path. He applied to study chemistry then, after two weeks, switched to study law and went on to become a Doctor of Law.

“But it was while this was all happening that he started to write. And it was this that changed his life and eventually turned him into a household name. A miraculous observer of people, he had, even as a youngster, noticed people’s features, gestures, and mannerisms. He had an intuitive understanding of the feelings of others, and this was one of the many sparks that inspired his writings.

“Kafka certainly was prescient. He never set himself up as any kind of prophet. But simply by delving deep within himself and by being so profound, so wise, he was able somehow to sense situations long before they became a reality. And when one looks at his works, and one considers he was writing over 100 years ago, his writing is still relevant and feels remarkably contemporary. His creativity and innovation have influenced many generations of artists, including scores of playwrights.”

The play transports us back in time to early 20th century Prague. Kafka and his writing are brought to life and given perspective in a journey that spans many decades and includes encounters with many notable people including scientist Albert Einstein and author Albert Camus.

Multi-award-winning actor Jack plays 49 characters. As he seamlessly changes roles the audience learns about the real Kafka – his family, his life, his loves, and his phenomenal talent. A one-man show, the story is told not by Kafka but through the eyes of his close friend, the Israeli-born author and biographer Max Brod. And it is to Max that the literary world owes a huge debt. When Kafka died, he left instructions for Max, as his executor, to destroy all his work. Not only did Max refuse to comply with this request, but he also managed to preserve the writings for future generations. Max protected the papers from Nazi hands during the Second World War by transporting them to Palestine. Then, when war in the Middle East looked imminent in 1956, he transported them to safety in the UK.

The idea of the play came to Jack in 1983. “I started to research Kafka and I realised how little I knew about him. I was mightily confused by the different views about him I came across,” says Jack. “The fact that Kafka was Jewish wasn’t mentioned at that time as much as it should have been. Jewishness permeates everything he writes. It’s quite right that he belongs to the world. But it’s magnificent that he is such a credit to the Jewish people.”

Kafka was brought up in Prague, the city of the Golem, and Jewish mysticism drew him in, “as did the Talmudic approach to any question, yet simultaneously he had a feeling, as a Jew, of somehow being an alien. In his life and in his writings many of his characters experience unease and awkwardness”, says Jack. “He was excited by Yiddish as a language. He wasn’t a campaigning Zionist, but he worked hard to learn Hebrew. And at the time that he was dying he talked seriously about moving to Palestine. His experiences as lawyer involved with workers’ compensation bolstered his unique insights into the worlds, the perspectives, the sufferings, and the agonies of many other people too.”

Kafka was brought up in Prague, the city of the Golem, and Jewish mysticism drew him in, “as did the Talmudic approach to any question, yet simultaneously he had a feeling, as a Jew, of somehow being an alien. In his life and in his writings many of his characters experience unease and awkwardness”, says Jack. “He was excited by Yiddish as a language. He wasn’t a campaigning Zionist, but he worked hard to learn Hebrew. And at the time that he was dying he talked seriously about moving to Palestine. His experiences as lawyer involved with workers’ compensation bolstered his unique insights into the worlds, the perspectives, the sufferings, and the agonies of many other people too.”

When the Yiddish theatre folk visited Prague, Kafka was a regular in the audience for their performances at the Café Savoy. Some Prague Jews looked down on these impoverished artists, but for Kafka they were full of life and he loved their spirit. “They brought to him what he felt Jewishness should be: the beautiful words, the wonderful, convoluted tales, and the laughter. They were modern people, but they carried within their souls a great tradition. He loved them,” says Jack. “The performances were diverse, and he was fascinated by performers such as Mrs Klug – a male impersonator – and in particular the actress Mania Czyzyk, for whom he carried a torch. He writes pages about her in his diaries,” says Jack. “He saw all humanity in one human being. He understood that there is a universal longing people have, in their deepest moments, when they want to understand what life is, why we are here, how we should live and where we are going.”

In some ways there are similarities between elements of Kafka’s and South African- born Jack’s lives. Both were brought up in traditional Jewish homes, but neither was particularly religious. Both studied law and then diversified into theatre and performance.

Jack came to the UK in 1973 to study at the Bristol Vic Theatre School. Originally intending to become a director, his tutors, recognising his acting talent, persuaded him to first tread the boards then to subsequently become a writer and director. His film credits include Star Wars and he has appeared in countless films, television and radio shows.

The staging of Kafka is a rare opportunity for audiences to see the impeccably researched play that Jack is reprising after its earlier run 35 years ago. This latest iteration of Kafka is true to the original version but has been slightly updated to include more recent research.

Jack says: “In Kafka we have before us the modern mind at its best. So I’m hoping to present all of humanity in this one wise human being. Kafka understood there is a universal longing people have, in their deepest moments, when they want to understand what life is, why we are here and how we should live.”

Kafka runs until 6 July at Finborough Theatre, Earls Court, with some performances already sold out. finboroughtheatre.co.uk

No comments:

Post a Comment