Op-Ed: Lightly-Armed Guards Are No Solution for Houthi Attacks

The world’s main shipping artery is under persistent and sophisticated threat, but the private maritime security industry promotes archaic, ineffective, and often misguided solutions to mitigate these risks. We are at a turning point in the market. Our industry can, as the saying goes, adapt or die. Upgraded equipment, enhanced rules-for-the-use-of-force (RUF), refreshed industry self-conceptualization, and rejuvenated security governance architecture are necessary to rise to the occasion and meet these threats head-on to protect the lives of seafarers and contracted maritime security guards alike.

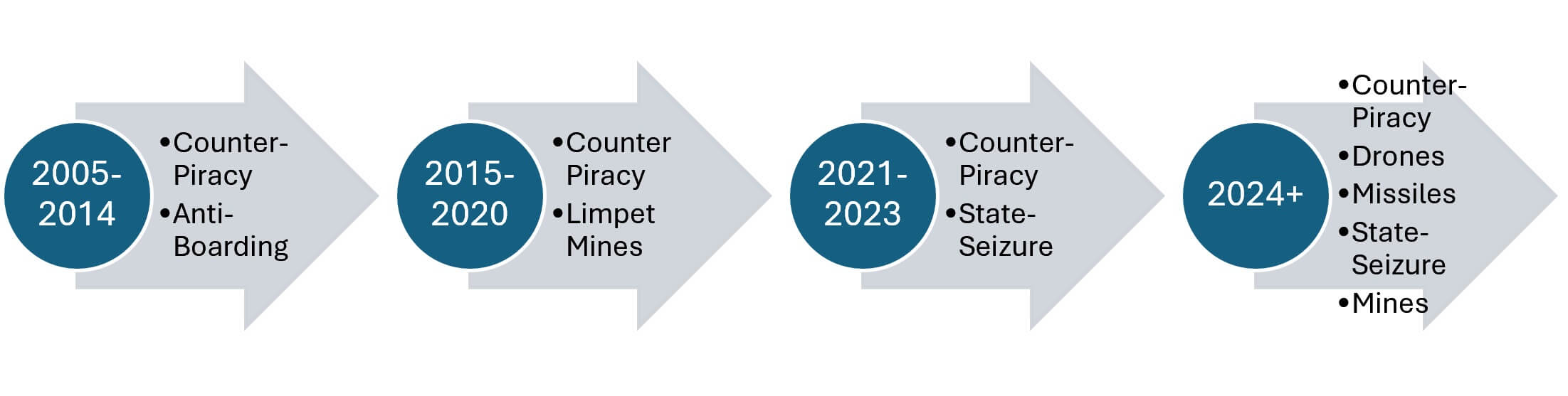

Seafarers and maritime security guards, and the vessels they work on, are being attacked by hostile state actors and non-state actors with state-like capabilities. These groups are targeting merchant and fishing vessels with drones, missiles, water-borne IEDs (WBIEDs), sea mines, limpet mines, and even undertaking unauthorized boarding by fast-boats and helicopters - resulting in numerous injuries and deaths, major damage to infrastructure and cargo, unlawful seizure and arrest of vessels, crew and guards, and even sunk vessels.

Although the threats are more sophisticated and serious than those faced in the past, the industry is still operating with personnel, policies, equipment, and a service model all designed for one purpose: prevention of boarding by pirates. This is insufficient for the modern threats faced in 2024, and necessitates a comprehensive industry reset and evolution.

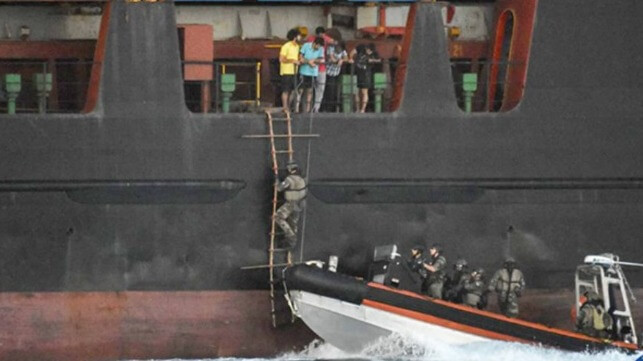

More than a decade ago, the contemporary private maritime security industry was born to deter and prevent the seizure of vessels by pirates off the coast of Somalia. This came as a private industry-led self-help measure where governments’ naval capability alone failed to eradicate the threat. The industry devised creative solutions to mitigate the piracy threat through a combination of specialized insurance contracts and physical loss prevention measures, chiefly armed security. Private Maritime Security Companies (PMSCs) deployed armed security teams in counter-piracy operations to deter and prevent pirate boardings.

More than a decade ago, the contemporary private maritime security industry was born to deter and prevent the seizure of vessels by pirates off the coast of Somalia. This came as a private industry-led self-help measure where governments’ naval capability alone failed to eradicate the threat. The industry devised creative solutions to mitigate the piracy threat through a combination of specialized insurance contracts and physical loss prevention measures, chiefly armed security. Private Maritime Security Companies (PMSCs) deployed armed security teams in counter-piracy operations to deter and prevent pirate boardings.

This action took the form of privately contracted armed security personnel (PCASP), commonly 3-4 guards, embarked on client vessels, usually with semi-automatic rifles, and strict RUF to deter and prevent boarding of armed pirates from the waterside, thwart their attempted hijacking of the vessel, and foil any attempts at kidnapping the crew. This solution was and remains maximally effective against the piracy threat. But identically cloning it in an effort to prevent drone and aerial attacks on merchant vessels is insufficient and irresponsible.

The primary clients of counter-piracy security providers in the maritime domain are almost exclusively other private companies: shipowners, charterers, cargo owners, and other enterprises operating vessels at sea, and not governments. As private companies, these clients are cost sensitive and it is their natural behavior to perpetually dampen prices of their vendors, including PMSCs.

As a result, the selling price of maritime security services has decreased many-fold over the last years, mainly driven by shipowners’ and operators’ relentless demands for lower rates and extended payment terms, which proved unsustainable for an otherwise healthy market. This low value placed on literally priceless, life-protecting services is especially ironic as the industry has witnessed the spawning of more sophisticated threats, increased client requests for services, and migrated, currently at an increasing cost, from traditional land-based logistics hubs to an almost completely offshore vessel-based-armory logistics footprint which is fully self-sustaining; all while contending with a largely laissez-faire - or in some cases even antagonistic - approach from governments.

It has been suggested that this reduced revenue earned by PMSCs has led to their cost-cutting on personnel and equipment, causing a cascading decrease in competency and quality of the PCASP, and their services rendered. This pattern came to be seen as a race to the bottom, as maritime security service providers chased large quantities of low-margin transits over niche quality-focused specializations in a competition for the remaining thin profits that could be extracted - always pushed by client shipowners and operators who demand ever-longer payment terms and ever-lower prices, with little to no regard for service quality so long as it meets the bare minimum industry standards.

Yet despite these industry-crushing financial pressures, the same shipowners and operators - along with other affiliated maritime sector stakeholders, including their insurers, lawyers, bankers, flag authorities, and industry trade associations - now increasingly demand that their maritime security service providers protect them from today’s more complex and lethal threats beyond piracy.

These threats are not only hostile boardings from the waterside, which PMSCs are more than capable of resisting, but now include sophisticated aerial attacks from drones, missiles, and helicopters. There are new advanced dangers from and below the water, like mines, WBIEDs, and subsurface weapons, which most of the private industry is not equipped to engage. The countermeasures for these threats requested by clients and other stakeholders - especially anti-aircraft capabilities and electronic or signals jamming systems - are not widely present in the industry, employed only by a minute selection of specialist PMSCs. As a result, most security service providers simply carry on using the same personnel with outdated tools and strategies from their existing counter-piracy arsenal, and all at the same laughably low price.

At a time when major governments are failing or refusing to defeat these new threats with billion-dollar warships, million-dollar air-defense systems, and no risk of bankruptcy - let alone litigation if anything goes amiss - it is too much to expect most PMSCs to succeed in defeating these threats. Private contractors would need superior, fit-for-purpose equipment that comes at a much higher price-point, and new rules and industry-accepted procedures, which may require a revision of current regulations and law.

When private companies are once again being asked to step in and perform the security tasks that governments abdicate, and when PMSCs lack the proper tools to achieve the given objectives, and when clients still demand these reinforced services at a lowball price, it's obvious that the system is fundamentally broken.

The colorful conversations in the industry, the armchair quarterbacking following widely-circulated videos of the unsuccessful thwarting of the WBIED attack on MV Tutor, and other recent incidents underscores that thoughtful discussions and real actions need to occur to resolve the threat-mitigation mismatch in today’s private maritime security industry. And not only by PMSCs: most serious market participants are acutely aware of the threats at sea and the limitations of their services, and may simply disagree on the best mitigation measures or most appropriate RUF. Rather, sincere introspection and hard decisions must also be taken by their clients - shipowners and operators - ideally leveraging their own data-driven voyage risk assessments, in order to accurately identify current threats. They need to reflect honestly, and with counsel, on their duty-of-care obligations to crew and contractors, and soberly evaluate whether their desired mitigations are even available in the market and realistically deliverable by their PMSC of choice.

A genuine meditation on this subject may lead responsible client shipowners and operators to realize that the threat-mitigation mismatch in today’s private maritime security industry is severe and dangerous. Which begs the question: Why are these clients continuing to accept a standardized suite of security services that does not protect them from today’s threats?

Not only is this mismatch a lack of task-appropriate equipment, such as anti-aircraft weapons, jamming and counter-drone technology, or other advanced defense systems, along with the commensurate pricing. Perhaps our wider industry’s conceptualization of the suite of maritime security services offered, RUF, policies, and procedures in place, and dare we say moral philosophy, also needs an overhaul?

With some PMSCs reportedly offering larger teams of more security guards, still armed with only semi-automatic weapons to defend against high-speed aerial threats, and with the audacity to promise clients that their guards will ‘fight-to-the-death,’ man-against-machine, without being given even the most basic tools to protect the vessel, cargo, crew, and themselves from high-technology threats - maybe we need to rethink our stance and our duty-of-care obligations too?

Is there a moral dilemma here where we are asking private security guards, deployed at sea on a salary of US$800 per month, handed the wrong equipment for the job, to sacrifice their lives in an attempt to defeat a state proxy-launched drone swarm to protect containers of mass-market clothing, or grain, or cars, or oil, and its conveyance and crew? They signed an employment contract, not a death warrant.

Would our military leaders send soldiers or sailors into this fight so ill-equipped? If not, why are we, as an industry, deploying our employees or contractors in such an unprepared and ineffective manner? What training, tools, policies, and support should they be provided, or at least permitted, in order to effectively meet the demands of the market, mitigate these threats, and live to fight another day?

Are they even issued the right tools to thwart an attack by one drone or one WBIED? What about a swarm of twenty suicide-drones? How about a simultaneous swarm of a dozen drones and a dozen WBIEDs which immobilize the vessel, immediately followed by a hostile helicopter and waterside combined boarding and seizure? Are you ready?

Better rise to the occasion. Because that’s what’s coming.

Simon O. Williams BA, LLM has built and managed several PMSCs currently active in this industry and serves as a consultant for numerous shipping and cruise lines and other organizations in the industry.

The opinions expressed herein are the author's and not necessarily those of The Maritime Executive.

No comments:

Post a Comment