The host of the 2034 international football competition has a gruesome record of violence against migrant workers.

By Yasin Kakande ,

December 18, 2024

Migrant workers are seen at a construction site near Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, on March 2, 2024.Jaap Arriens / NurPhoto via Getty Images

Independent journalism like Truthout has been struggling to survive for years – and it’s only going to get harder under Trump’s presidency. If you value progressive media, please make a year-end donation today.

FIFA has officially announced Saudi Arabia as the host of the 2034 World Cup, marking the second time the prestigious tournament will be held in a Gulf Arab nation and following Qatar in 2022. Saudi Arabia’s ambitious plans include building or renovating 15 stadiums, constructing over 185,000 hotel rooms, and executing massive infrastructure projects to welcome the mass influx of spectators.

However, this announcement has sparked widespread criticism, with Human Rights Watch (HRW) labeling the bid as a blatant example of “sportswashing.” By leveraging high-profile events like the World Cup, critics argue that the Saudi regime seeks to divert attention from its troubling human rights record, using sports to launder its international reputation while repression and authoritarian rule persist.

As someone who documented the abuses against migrant workers during Qatar’s 2022 preparations, this new plan for Saudi Arabia presents me with another reason to expose these persistent injustices. My work as a journalist and activist involved visiting construction sites where laborers toiled under scorching heat, denied basic rights like adequate breaks and humane living conditions. Those efforts not only led to articles and the publication of my books, Slave States and The Ambitious Struggle, but also resulted in my eventual expulsion from the region.

My ordeal began when my editor called me into his office, his face heavy with the burden of what he was about to say. “You’ve committed a grave sin” in the eyes of the UAE government, he said, referring to the book I had published without the government’s approval. The authorities were outraged, and they demanded that the newspaper terminate my employment and send me back to Uganda. Although the situation was dire, I felt a sense of gratitude when my editor managed to secure a one-month grace period for me — time to withdraw my children from school, surrender my apartment, and sell my car before I was forced to leave the UAE.

My book The Ambitious Struggle was primarily an autobiographical novel — though it did not solely recount my own story. It wove together the tales of countless migrants who, like myself, had ventured to the affluent Gulf states in search of opportunity. Across the world, migrant workers faced immense challenges, whether in Europe or America, but these struggles were particularly harrowing in the Gulf. The kafala system is a longstanding legal framework in Arab Gulf countries that gives employers near-total control over migrant workers’ employment and immigration status. This system often subjects workers — primarily from poor Asian and African countries — to exploitation and conditions resembling bonded labor, trapping them in cycles of servitude. This system, unchecked, stripped countless individuals of their dignity, forcing them into lives of hardship and submission.

Related Story

Independent journalism like Truthout has been struggling to survive for years – and it’s only going to get harder under Trump’s presidency. If you value progressive media, please make a year-end donation today.

FIFA has officially announced Saudi Arabia as the host of the 2034 World Cup, marking the second time the prestigious tournament will be held in a Gulf Arab nation and following Qatar in 2022. Saudi Arabia’s ambitious plans include building or renovating 15 stadiums, constructing over 185,000 hotel rooms, and executing massive infrastructure projects to welcome the mass influx of spectators.

However, this announcement has sparked widespread criticism, with Human Rights Watch (HRW) labeling the bid as a blatant example of “sportswashing.” By leveraging high-profile events like the World Cup, critics argue that the Saudi regime seeks to divert attention from its troubling human rights record, using sports to launder its international reputation while repression and authoritarian rule persist.

As someone who documented the abuses against migrant workers during Qatar’s 2022 preparations, this new plan for Saudi Arabia presents me with another reason to expose these persistent injustices. My work as a journalist and activist involved visiting construction sites where laborers toiled under scorching heat, denied basic rights like adequate breaks and humane living conditions. Those efforts not only led to articles and the publication of my books, Slave States and The Ambitious Struggle, but also resulted in my eventual expulsion from the region.

My ordeal began when my editor called me into his office, his face heavy with the burden of what he was about to say. “You’ve committed a grave sin” in the eyes of the UAE government, he said, referring to the book I had published without the government’s approval. The authorities were outraged, and they demanded that the newspaper terminate my employment and send me back to Uganda. Although the situation was dire, I felt a sense of gratitude when my editor managed to secure a one-month grace period for me — time to withdraw my children from school, surrender my apartment, and sell my car before I was forced to leave the UAE.

My book The Ambitious Struggle was primarily an autobiographical novel — though it did not solely recount my own story. It wove together the tales of countless migrants who, like myself, had ventured to the affluent Gulf states in search of opportunity. Across the world, migrant workers faced immense challenges, whether in Europe or America, but these struggles were particularly harrowing in the Gulf. The kafala system is a longstanding legal framework in Arab Gulf countries that gives employers near-total control over migrant workers’ employment and immigration status. This system often subjects workers — primarily from poor Asian and African countries — to exploitation and conditions resembling bonded labor, trapping them in cycles of servitude. This system, unchecked, stripped countless individuals of their dignity, forcing them into lives of hardship and submission.

Related Story

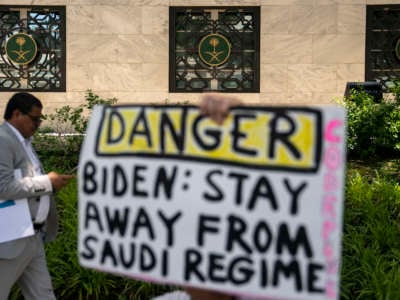

Saudi Arabia Is Using Biden’s Visit and Sports-Based PR to Hide Its Crimes

Biden has decided to forego Saudi-related campaign in order to try to reduce gas prices before the midterms. By William Rivers Pitt , Truthout July 12, 2022

International tournaments like the World Cup draw the world’s gaze to host nations, creating a rare opportunity for advocates to shed light on systemic abuses that might otherwise remain hidden.

During my time as a reporter for The National, I reported on the harrowing case of an Emirati sponsor who admitted to police that she had beaten her Sri Lankan maid to death with a wooden cane for being “lazy.” The woman’s lifeless body was found discarded in a bathtub, her skull fractured, her teeth broken, and her arms and legs marred with bruises — a brutal testament to the inhuman treatment that ended her life. In another heart-wrenching case, I uncovered the murder of an Ethiopian maid at the hands of an Arab family, who callously burned her body before abandoning it in Abu Dhabi’s Ajban desert. In another instance of abuse, a 23-year-old Ethiopian maid in Dubai was burned with cooking oil by her Arab employer, an act of cruelty that still haunts me to this day.

These stories, unfortunately, were not isolated incidents. The catalogue of abuse seemed unending, not just in the UAE, but across the Gulf region, making these countries some of the most perilous places to be a domestic worker. In Saudi Arabia, a 23-year-old Indonesian maid, Sumiati Binti Salan Mustapa, was taken to hospital with broken bones and severe burns, after her employer pressed a hot iron to her head and stabbed her with scissors. The employer was initially sentenced to three years, but she was swiftly acquitted in appeal, her crime overshadowed by claims of self-defense and the impenetrable protection granted by the kafala system.

In another horrific case, a Sri Lankan maid was found with 24 nails and a needle embedded in her body, the result of unimaginable torture. Some maids, like Ruyati binti Sapubi from Indonesia and Rizana Nafeek from Sri Lanka, were executed (beheaded) after rushed and unjust trials for alleged crimes, such as murder. The legal process was often swift and biased, allowing employers to exploit the kafala system to shield themselves while denying the accused a fair defense.

These stories resonated deeply with me, as I was a migrant myself. While my position as a journalist afforded me a certain level of status and privilege — allowing me to retain control of my own passport and those of my family, and enabling me to change jobs — I was still a member of the migrant community. All my friends, and many of my sources for stories, were also migrants. It was because of this shared experience that I dedicated my profession to exposing the atrocities suffered by migrant workers and bringing these injustices into the public eye for scrutiny.

However, it wasn’t long before the UAE government clamped down on my efforts to report and document these abuses, all in the name of protecting the country’s image and safeguarding the political economy. The subtle censorship filtered down through my editors, who began to reject my daily pitches exposing the violence and exploitation that plagued the migrant workforce — from unsafe, unregulated working conditions and squalid housing to unpaid wages, rape, torture and murder. It became increasingly clear that the powers that be would not tolerate anything that risked casting a shadow over the country’s reputation.

One particular story that I pitched, which was ultimately rejected, deeply affected me. It was the case of Khurshid, an Indian worker who perished in a petrochemical fire at the National Paints factory in Sharjah.

Migrant laborers who have been silenced and kept out of media stories are now standing up for their rights, often at immense personal risk.

Khurshid lived in Sharjah with his brother, Tabreer Ahmed. On that tragic day, he had gone to work as usual, but disaster struck when the factory caught fire. He had been assisting in extinguishing the blaze when he lost his life. When Khurshid didn’t return home that evening, his brother went to the charred remains of the factory in search of answers. Speaking to Khurshid’s colleagues, he learned that his brother had died in the fire, but when he approached the factory owners, they flatly denied that any of their workers had been killed. In fact, they claimed they had never employed Khurshid at all. Desperate, Tabreer reached out to me for help, and I joined him in the search for his brother and the truth. We visited the Sharjah Civil Defence, the police — but each denied there had been any fatalities. It wasn’t just Khurshid. There were two other families who had also lost sons in the blaze, and I met with them as well.

I presented all these details to my editors, only to be told that there was no story to publish if officials were denying the deaths. Two months later, the bodies of three workers were discovered on site by other laborers clearing the premises. I was among the first reporters called to the scene, and I attempted to take photographs. But when the police arrived, they deleted my images and confiscated my camera. My editor was furious that I had insisted on pursuing the story, yet when he learned that rival publications were now chasing it as well, he begrudgingly agreed to publish a small piece that downplayed the three men’s deaths.

That incident was the turning point for me. It spurred me to write my first book, an attempt to chronicle every untold story I was unable to publish in the newspaper I worked for. These stories deserved to be written, even if no one was willing to print them.

International tournaments like the World Cup draw the world’s gaze to host nations, creating a rare opportunity for advocates to shed light on systemic abuses that might otherwise remain hidden. Even after my expulsion from the Gulf silenced my voice in the region, the flame of activism has only grown stronger. Migrant laborers who have been silenced and kept out of media stories are now standing up for their rights, often at immense personal risk. Through protests, social media and acts of defiance, they are making their voices heard, challenging a system that once thrived on their silence.

As a journalist and activist, I view Saudi Arabia’s successful bid to host the 2034 World Cup as more than a sporting achievement; it is another opportunity to expose human rights abuses on a global stage.

This article is licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), and you are free to share and republish under the terms of the license.

Yasin Kakande, is an international journalist, a TED Global Fellow, and the author of a number of critically acclaimed nonfiction books offering a fresh perspective on immigration and geopolitics, including Why We Are Coming and Slave States. As a migrant from Uganda now based in the US. following asylum, his journalism career spans international outlets including The New York Times, Thomson Reuters, Al Jazeera, The National, and The Boston Globe. His latest book, A Murder of Hate, is out now.

No comments:

Post a Comment