New Models Could Help African Countries Stop Locust Swarms Before They Start

HENRI TONNANG, THE CONVERSATION

21 NOVEMBER 2020

Several countries in East Africa – namely Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda, and South Sudan – are still trying to contain the worst desert locust invasion the region has experienced in over 70 years.

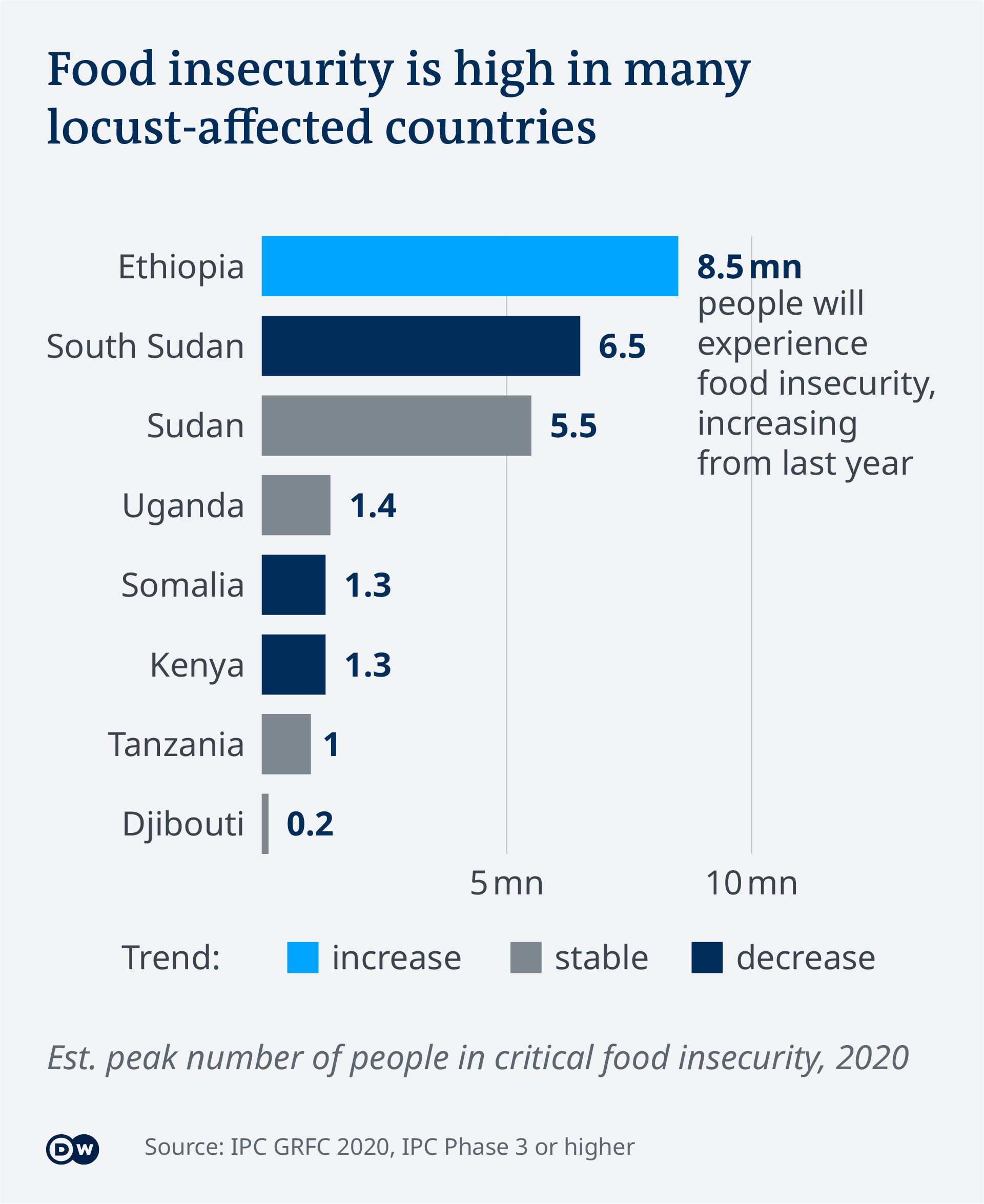

The locusts have destroyed vegetation – especially staple cereal crops, legumes, and pastures – resulting in huge economic losses. The World Bank estimates that these losses could reach US$8.5 billion by the end of the year.

Unlike many other grasshoppers, the desert locust (Schistocerca gregaria) can change from a harmless solitary phase to a destructive gregarious phase whereby hoppers (juveniles in their early, wingless stages) march together in bands.

The adults can fly and form giant swarms that can invade large areas away from their original breeding sites.

Currently, the countries are battling the second generation (or wave) of locusts, as they've already reproduced and hatched once within the region. And re-infestation could continue if the environment is conducive to it.

The desert locust breeds well in semi-arid zones. An ideal breeding site is characterised by warmth, vegetation close by and sandy soil with moisture and salt in it. The females usually lay their eggs at between 4 and 6 cm deep in the soil.

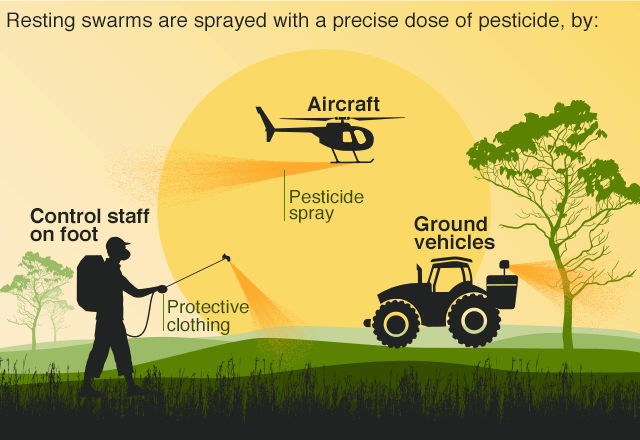

Governments have tried to control these insects through a range of efforts: from mobilising military units to using young people as locust cadets.

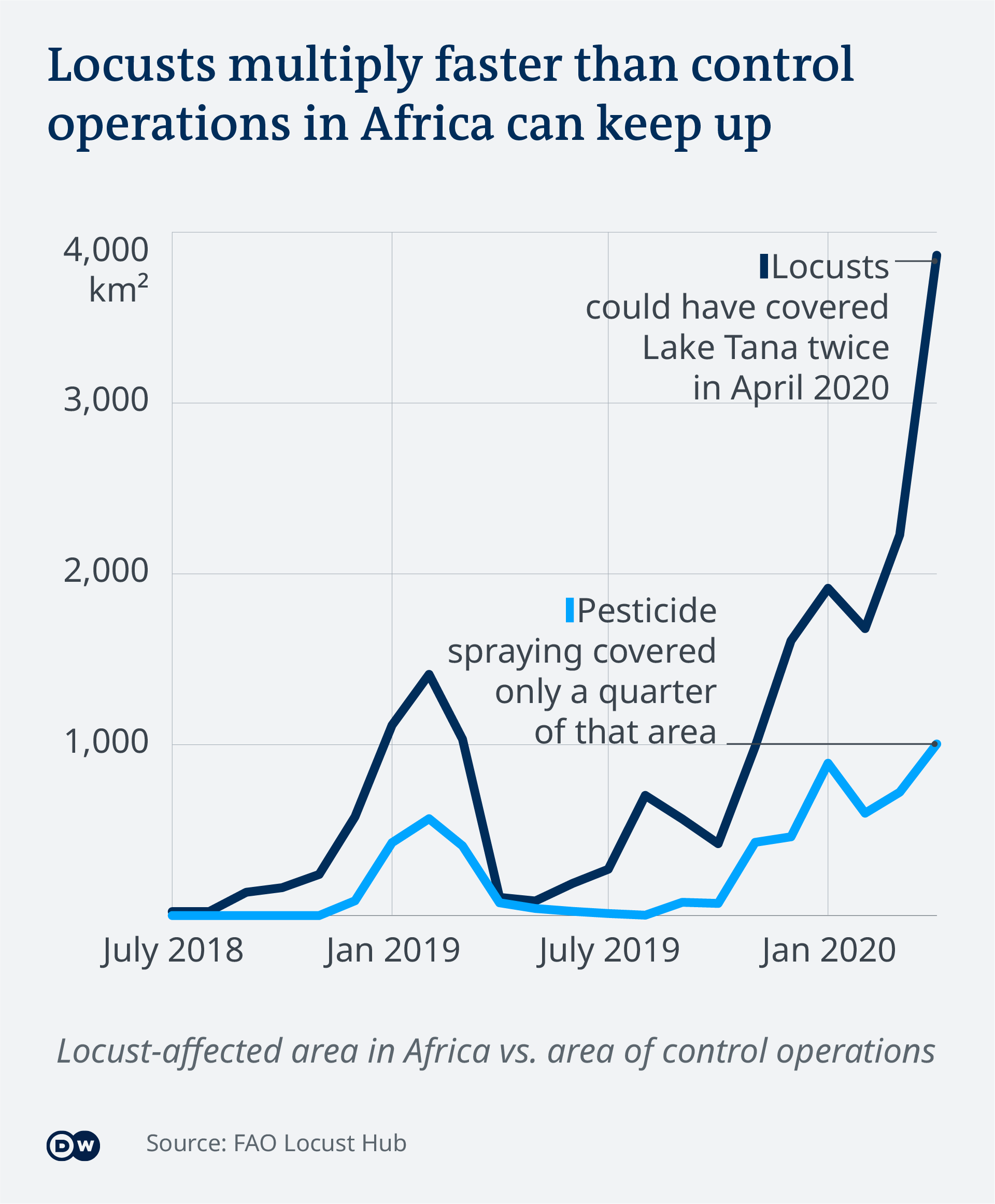

But trying to control and eliminate populations of flying locusts is expensive and not very effective. The best option, proved by scientists, is to manage them at their breeding sites.

Eggs survive and hatch when the environmental conditions are right – they can hatch within weeks or remain undeveloped for years. They're laid inside soil so can be hard to find; it's best that control measures – preferably biopesticides – are used when the locusts are at the surface in the form of a nymph or hopper.

For this to happen, targeted ground and aerial surveillance efforts to identify potential breeding sites are critical.

The most destructive locust swarm in East Africa happened over 70 years ago. Documentation of information was very poor, and so there was no prior knowledge of the region's potential breeding sites.

Along with my colleagues from the International Centre for Insect Physiology and Ecology, I'm trying to fill this gap. We've developed maps that predict where desert locusts could breed in Kenya, Uganda, and South Sudan.

Our model, supported by a machine learning algorithm, establishes a relationship between historical data from around the world on desert locust breeding sites.

It also factors in climate and soil characteristics that are necessary for locusts to lay their eggs, and for the eggs to hatch.

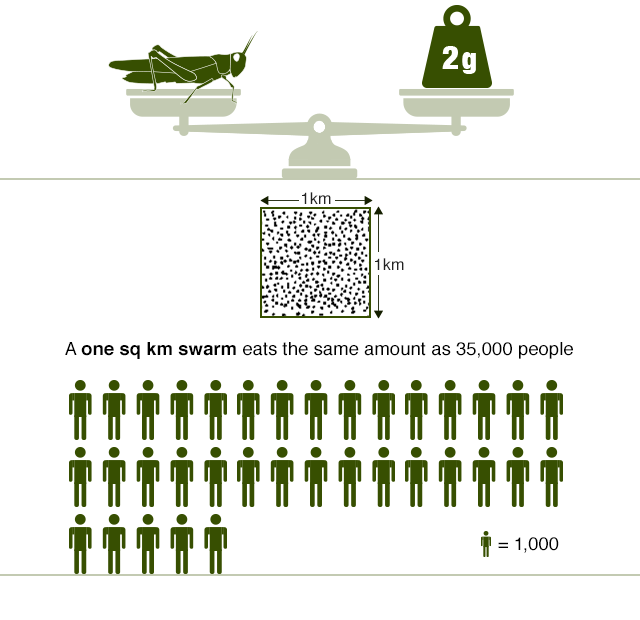

Breeding sites can consist of anywhere between 40 to 80 million locusts within a square kilometre.

There is a need to target these high-risk areas and strengthen ground surveillance to manage the locusts in a timely, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly manner.

At-risk areas

Using the model, we've identified and mapped potential breeding regions of the desert locust in Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan.

Vast areas in Kenya are at high risk because they have the right conditions to support locust breeding. These areas include Mandera, Wajir, Garissa, Marsabit, Turkana (all counties in North Eastern Kenya), and a few sites in Samburu county.

In Uganda, there are fewer possible breeding sites than in Kenya. These are restricted to the north-eastern regions, specifically Kotido, Kaabong, Moroto, Napak, Abim, Kitgum, Moyo, and Lamwo districts.

South Sudan is at risk of breeding in the northern regions and the south-east corner bordering Kenya. These sites exist in northern Bahr el Ghazal, Unity, Upper Nile, Eastern Equatoria, Warrap, Lakes, and some parts of Jonglei state.

Actions

In line with these predictions, ground and aerial surveillance efforts and monitoring of weather and vegetation variables in the predicted breeding regions needs to be strengthened significantly.

Financial, material and human resources will also need to be mobilised for timely management of the hopper bands when they emerge.

We, at the International Centre for Insect Physiology and Ecology, have several suggestions on what must happen next:

Due to a large area for potential breeding of locusts, a permanent locust monitoring unit in Kenya must be established. It should consist of ground and aerial surveillance teams, locust biologists, socio-economists, remote-sensing experts and weather and vegetation forecasters.

A task force must be set up in Uganda to collaborate with Kenya's monitoring unit. Based on the overall cover area of desert locust breeding suitability in Uganda, it may not be necessary to invest in constant monitoring in the country.

But the task force must collaborate closely with the Kenyan Locust monitoring unit and enhance preparedness for possible outbreaks and swarms.

Sustainable locust management interventions and associated mobilisation of financial, logistical and human resources need to be closely linked with strengthened locust monitoring efforts.

There must be a greater focus on sustainable and biological control options against locusts to mitigate adverse impacts of chemical pesticide-based locust control strategy.

We believe that biopesticide applications should become a cornerstone in managing locust outbreaks. Biopesticides need to be rapidly field tested in Kenya, commercialised and scaled up.

Finally, the current desert locust outbreak is triggered by a change in rainfall pattern which expands areas of potential invasion as a consequence of climate variability or change.

It is possible that, in future, other marginally suitable areas and conditions may become conducive for locust breeding.

Therefore, it is important to ramp up modelling efforts to understand the potential impacts of climate change on the current model predictions.

Henri Tonnang, Research Scientist, International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Climate change is worsening the largest plague of the crop-killing insects in 50 years, threatening famine in Africa, the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent.

BY BOB BERWYN, INSIDECLIMATE NEWS

MAR 22, 2020

Millions of locusts swarm in Tsiroanomandidy, Madagascar.

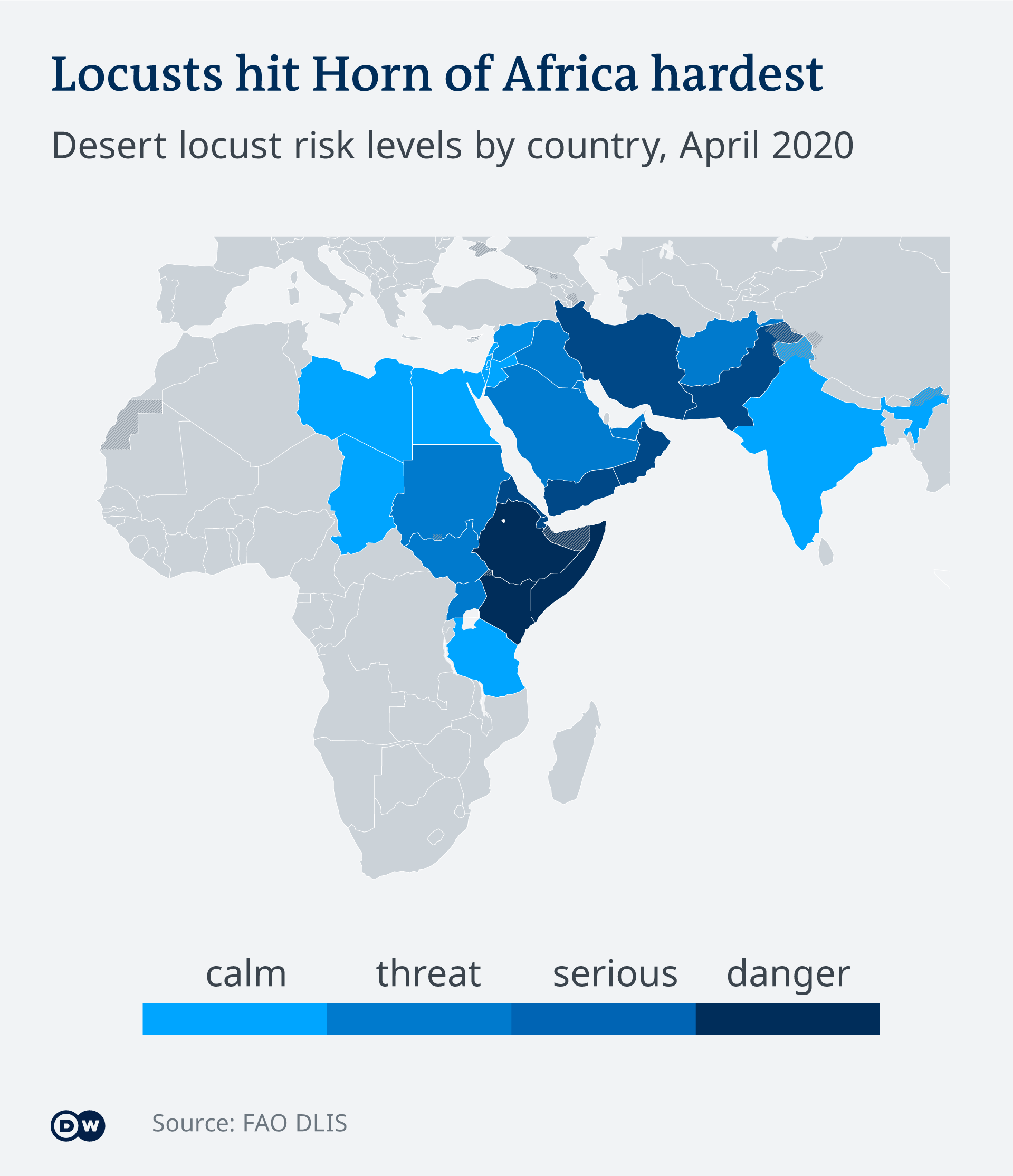

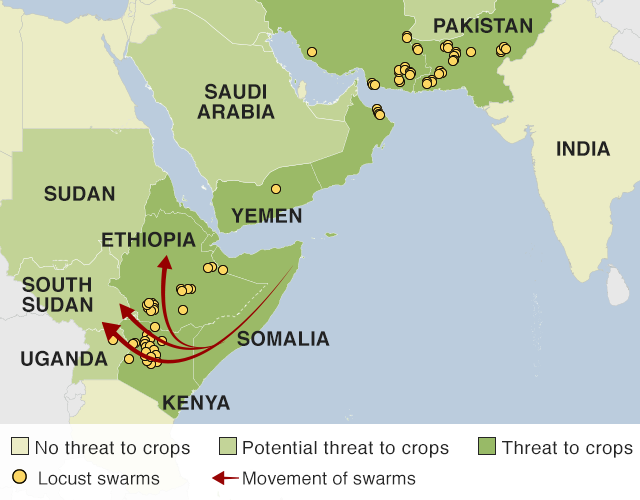

As giant swarms of locusts spread across East Africa, the Arabian Peninsula and the Middle East, devouring crops that feed millions of people, some scientists say global warming is contributing to proliferation of the destructive insects.

The largest locust swarms in more than 50 years have left subsistence farmers helpless to protect their fields and will spread misery throughout the region, said Robert Cheke, a biologist with the University of Greenwich Natural Resources Institute, who has helped lead international efforts to control insect pests in Africa.

"I'm concerned about the scale of devastation and the effect on human livelihoods," Cheke said, adding that he also worried about "the impending famines."

"Despite the coronavirus pandemic, the region needs money and equipment to deploy insect control teams in the affected regions," he said.

New swarms are currently forming from Kenya to Iran, according to the the United Nations locust watch website. Addressing the outbreak requires urgent, additional funding and technical help from developed countries, Cheke said, because the tiny size and budget of the United Nation's Food and Agricultural Organization team responsible for locust monitoring and control is already overwhelmed.

Changes in plant growth caused by higher carbon dioxide levels, as well as heat waves and tropical cyclones with intense rains, can lead to more prolific and unpredictable locust swarming, making it harder to prevent future outbreaks.

The desert locust (Schistocerca gregaria) needs moist soil to breed. When rains are especially heavy, populations of the usually solitary insects can explode. In Kenya, one of the biggest swarms detected last year was three times the size of New York City, according to a March 12 article in the journal Nature. Swarms a fraction of that size can hold between 4 billion and 8 billion locusts.

At times, the locusts in East Africa have swarmed so thick that they have prevented planes from taking off and their dead bodies have piled up high enough to stop trains on their tracks.

Global Warming's Many Impacts on Insects

The changing climate has spurred other insect invasions. Warmer winters, for example, are magnifying an ongoing bark beetle outbreak in western North America. Until the 1980s, periodic cold snaps kept the beetles in check. But since then, the tree-killing bugs have swarmed—not as fast as desert locusts, but just as destructively. Since 2000, they've killed trees across about 150,000 square miles in Canada and the western U.S., an area nearly the size of California. In recent years, historic bark beetle outbreaks have also devastated European forests.

Other research shows that seasonal shifts caused by global warming are disrupting cycles of insect reproduction and plant pollination, including a recently documented decline of bumblebees, threatening food production in some areas.

Global warming is also affecting the feeding and breeding patterns of North America's grasshoppers, species that behave similarly to locusts. In the 1930s, swarms of grasshoppers destroyed crops in the Midwest, even eating wooden farm tools and clothes that were drying outside. States like Colorado used flamethrowers and explosives to battle the insects.

It's hard to predict how grasshoppers will respond to today's changing climate, said University of Oklahoma biologist Ellen Welti, who studies the relationship between insects and plants.

But, she said, "Warmer winters, with less egg mortality and changes in precipitation patterns that affect the amount and quality of plant food, could lead to outbreaks of particular grasshopper species or other herbivorous insects."

Locust outbreaks could be driven by changes in plant nutrients caused by extreme weather, Welti said, like more frequent soggy tropical storms, which make plants grow faster but dilute elements like nitrogen. "Locusts have a weird physiology—they like low nitrogen plants," she said of connections she explored in a recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

But the current locust outbreaks, Welti said, are occurring against the backdrop of an alarming global decline in overall insect abundance, which is also, to some degree, connected to climate change and will have far-reaching ecosystem impacts.

Extreme Weather, Failed Governance Favor Swarms

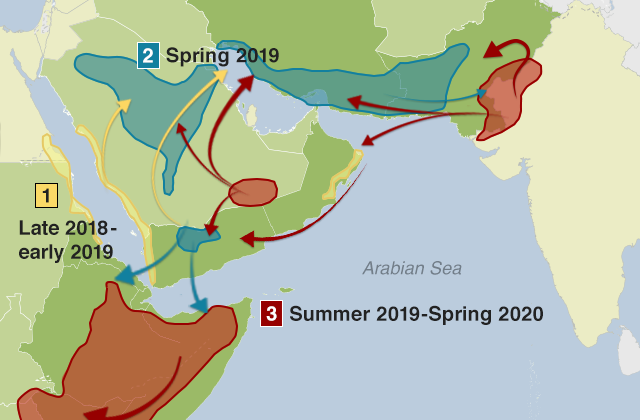

Warm weather and heavy rains at the end of 2019 set up a perfect storm of breeding conditions for the destructive bugs. The outbreak followed an unusually active West Indian Ocean cyclone season with several of the storms bringing extreme rainfall to parts of East Africa.

Studies in the last few years have showed that global warming is boosting the rainfall from tropical storms. Other recent research shows that human-driven warming may be intensifying a regional Indian Ocean pattern of warming and cooling that could exacerbate extremes like tropical storms, heavy rains and heat waves—all factors that can affect locust populations.

More moisture is a double-edged sword for the Horn of Africa, said Maarten van Aalst, director of the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre, which addresses the human impacts of climate change.

"We need rain for agricultural productivity, but it is then also conducive to locust breeding," van Aalst said. "It's a classical case of rising risks partly due to rising uncertainties. But we can manage some of this uncertainty. In this case we have had good predictions of elevated risks, and it is concerning that it still takes us so long to respond."

Martin Huseman, head of the entomology department at the University of Hamburg Center for Natural Sciences, said, "In general I think it's partly climate change. We get more extreme weather conditions. The cyclones we had there in the region could lead to enhanced swarming."

Locusts swarm out to find more food when they reach extremely dense populations during the nymph stage of their development. Aided by wind, the insects can travel more than 90 miles per day. Scientists warn they could spread across hundreds of thousands more square miles from Ethiopia and Saudi Arabia to Sudan, and across the Persian Gulf and Arabian Sea into Iran, Pakistan and India. Such a spread would threaten the food supplies of 20 million people.

Those food shortages will mainly be felt later in the year, so there is still time to act by bolstering regional food supplies, van Aalst said. But travel restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic will challenge locust control projects, as well as relief efforts. According to the UN's locust watch program, the countries facing the biggest risk are Kenya, Ethiopia, Somalia, Iran, Pakistan and Sudan.

Cheke said poor monitoring, conflict and a breakdown of governance in key locust breeding areas enabled the recent outbreak to grow unchecked, and threatens the progress made in controlling locusts during the last half century.

"It all started with substantial rainfall in May and October 2018 allowing good desert locust breeding in the Empty Quarter of the Arabian Peninsula to continue until March 2019, where it was not noticed and thus left uncontrolled," he said.

Swarms Could Expand Their Range and Emerge More Frequently

Huseman said that, in the global warming era, other parts of the world may also need to prepare for unexpected insect invasions as part of larger scale shifts in the distribution of animals. In northern Germany, for example, scientists recently spotted Asian wasps for the first time. A 2013 study found that crop-damaging insects are moving poleward at about 4 miles per year.

In addition to the ongoing plague of locusts around the Horn of Africa, there have been recent outbreaks of varying intensity in places like Sardinia, in the Mediterranean Sea, and Las Vegas.

David Inouye, a University of Maryland biologist who studies the effects of global warming on plants and animals, said conditions favoring outbreaks are becoming more common.

"I think that there is the potential for locust swarms to become more frequent, and potentially more widely distributed, as the environmental factors like rain and warm temperatures that favor their outbreaks continue to become more prevalent," he said. Some insects have a strict biological clock, but locusts respond strongly to environmental factors like precipitation and temperature.

Arianne Cease, a researcher at Arizona State University's School of Sustainability, said there are other factors related to climate that could promote locust swarms. Livestock grazing, rising carbon dioxide levels and extreme rainfall all lower nitrogen levels in plants—exactly the conditions that locusts thrive on.

"However," she said, "a direct link between atmospheric CO2, plant nutrients and swarming grasshoppers or locusts has yet to be tested, to my knowledge."

Cheke said it's unlikely, but possible, that locusts could swarm into new regions.

"With climate change it is possible that increasing aridity or changes in rainfall patterns could lead to locusts expanding their usual geographical range," he said. "For instance, in October 1988 desert locusts crossed the Atlantic but the habitat on the other side was unsuitable. Similarly, there are cases of desert locusts reaching the U.K. and Italy."

He believes several important questions remain to be answered, including whether locusts' speed of development from egg to maturity—which is temperature dependent—has increased in line with global warming.

"What I think is worth considering is whether climate change has led to habitat changes," he said. "Or changes ... regarding rainfall that might facilitate the success and spread of a locust plague once it has started. Or if climate change, through its effects on weather changes, could lead to changes in the locusts' usual migration routes."

In Africa, some of those questions have already been answered. Colin Everard, formerly with the Royal Aeronautical Society (U.K.), worked on locust control in Africa for 40 years. The increase in regional tropical cyclone activity during the last few years is certainly a factor, he said, as such storms are known to cause locust plagues.

"If this trend continues, for sure there will be more desert locust outbreaks in the Horn of Africa," he said. "There will be hunger and starvation in northeastern Kenya, the area which borders Somalia. Apart from humans, livestock will also starve to death due to the destruction of grazing."