Researchers say that if crater samples collected by the Mars 2020 rover are successfully returned to Earth, they have an idea for how to determine if water on the planet was once able to support life.

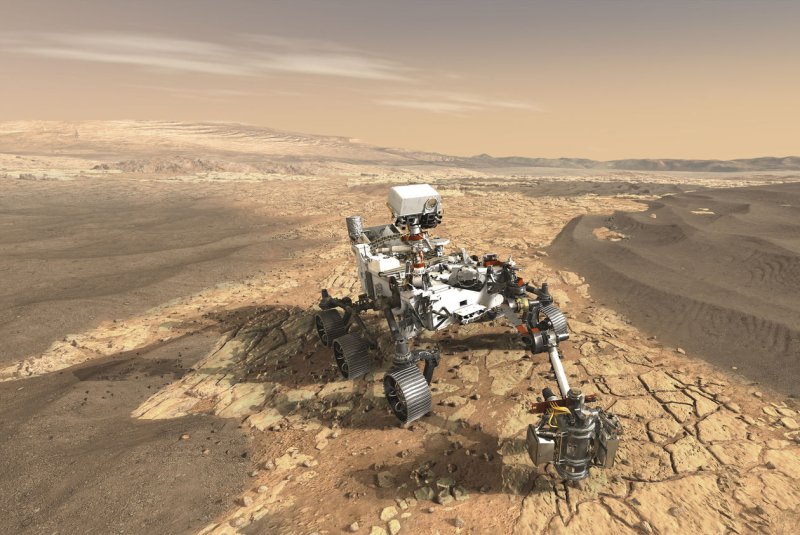

In an artist's conception, the Mars 2020 rover is seen introducing a drill that can collect core samples of the most promising rocks and soils and set them aside on the surface of Mars. A future mission could potentially return these samples to Earth. File Photo by NASA/UPI | License Photo

Feb. 27 (UPI) -- Planetary scientists agree that Mars once hosted significant amounts of water on its surface. But how the planet held onto to its water and whether or not its water could have supported life remain open questions.

For clues as to what a watery Mars would have looked like, scientists turned to a crater on Earth, the Nordlinger Ries crater in southern Germany.

"Ries is an impact structure, analogous to many of the impact features on Mars that held water in the past," Tim Lyons, professor of biogeochemistry at the University of California Riverside, told UPI in an email. "While there are differences, the impact breccia layer on Reis is very similar to features seen on Mars."

By studying the composition of Ries and the ancient weathering processes that made its breccia look the way it does, scientists were able to get a sense of how Martian crater samples might offer clues to the composition of the Red Planet's ancient atmosphere.

RELATED NASA's InSight lander mission yields first scientific paper on Marsquakes

The concentration of nitrogen isotopes and other minerals measured in Ries rock samples suggest the ancient crater site was exposed to water with high alkalinity and a high pH.

Mars receives significantly less thermal energy from the sun than Earth. For the cold, distant planet to have hosted ocean-like bodies of water some 4 billion years ago, scientists estimate the Mars' atmosphere would have had to contain large amounts of greenhouse gases -- specifically, CO2.

Their analysis of Ries crater rock samples -- detailed this week in the journal Science Advances -- suggest weathering by an atmosphere rich in CO2 would likely produce Martian crater rock samples featuring the chemical signatures of high alkalinity and a low or neutral pH.

The concentration of nitrogen isotopes and other minerals measured in Ries rock samples suggest the ancient crater site was exposed to water with high alkalinity and a high pH.

Mars receives significantly less thermal energy from the sun than Earth. For the cold, distant planet to have hosted ocean-like bodies of water some 4 billion years ago, scientists estimate the Mars' atmosphere would have had to contain large amounts of greenhouse gases -- specifically, CO2.

Their analysis of Ries crater rock samples -- detailed this week in the journal Science Advances -- suggest weathering by an atmosphere rich in CO2 would likely produce Martian crater rock samples featuring the chemical signatures of high alkalinity and a low or neutral pH.

RELATED Mars loses water to space during warm, stormy seasons

"Under extreme CO2 conditions, as might have been required on Mars, the alkalinity production is driven by very high rates of weathering linked to the high CO2," Lyons said. "But the high CO2 would also interact with the lake waters, keeping the pH comparatively lower."

By gaining a better understanding of the relationship between nitrogen isotopes in rock samples and the pH levels in ancient water, scientists will have a better idea of what to look for in Martian crater samples when the Mars 2020 rover touches down on the Red Planet next year.

When those crater samples are returned to Earth in a decade, scientists will be able to measure nitrogen isotope ratios and determine whether there were indeed high levels of carbon dioxide in Mars' ancient atmosphere.

"Under extreme CO2 conditions, as might have been required on Mars, the alkalinity production is driven by very high rates of weathering linked to the high CO2," Lyons said. "But the high CO2 would also interact with the lake waters, keeping the pH comparatively lower."

By gaining a better understanding of the relationship between nitrogen isotopes in rock samples and the pH levels in ancient water, scientists will have a better idea of what to look for in Martian crater samples when the Mars 2020 rover touches down on the Red Planet next year.

When those crater samples are returned to Earth in a decade, scientists will be able to measure nitrogen isotope ratios and determine whether there were indeed high levels of carbon dioxide in Mars' ancient atmosphere.

Ruffed lemurs provide vital ecosystem services to Madagascar's rainforest by spreading a variety of seeds across the forest floor. Photo by Rabe Franck/CUNY

Ruffed lemurs provide vital ecosystem services to Madagascar's rainforest by spreading a variety of seeds across the forest floor. Photo by Rabe Franck/CUNY