Is Afghanistan Once Again Becoming A Battleground For Major Powers? – OpEd

Why is Afghanistan always in trouble?

The sufferings of Afghanistan in the distant past and current difficulties are in large measure the product of its geographical location combined with its mines and minimal wealth, water resources, and mostly due to their constant internal conflicts. These factors have resulted in a troubled history since the beginning and produced a venerable state Afghanistan open to meddling from a range of external powers.

Neville Teller, a graduate of Oxford University has rightly summed up Afghanistan. According to him, certain areas of the world, simply on account of their geographical location, seem destined to be perpetual trouble spots. One such unhappy country is Afghanistan. Because of its position plumb in the middle of central Asia, Afghanistan is a prize that has been fought over and won by foreign occupiers many times in its long history. Its domestic story is equally turbulent, with warring tribes battling it out over the centuries for power and control.

Recorded history tells us that Afghans have been engaged with external enemies to protect themselves and their land for the last five thousand years. The Afghans have faced more invasions on their land than any other people in the world. Whether they were Greeks, Kushans, Mongols, Turks, white Huns, Persians, Mughals, and especially the British imperial forces in the nineteenth century after Afghans achieved unity first under the command of Mirwais Hotak, who successfully revolted against the Safavids in the city of Kandahar in 1707, and later on by the young Ahmad Shah Durrani in 1747. The geography of Afghanistan at that time extended up to Isfahan present-day Iran including most of present-day Pakistan and emerged on the world map as an independent nation in the early 18th century.

Geo-strategic location and importance of Afghanistan

Afghanistan has been at the heart of networks: a roundabout, a place of meetings, civilizations, religions, cultures, and of course, armies’ traders and pilgrims. Centuries on, Afghanistan enjoys the same status as the principal connector of the North and South and the East and West. It sits at the heart of Central Asia, at the meeting point of ancient trade routes – known together as “The Silk Road” – that goes out to all parts of Asia.

Due to its geostrategic importance, Afghanistan faced the outrage of British imperialism when the First Anglo-Afghan War was fought between them in the year 1838 to 1842. The second Anglo-Afghan War from 1878 to 1880 resulted in the division of Afghanistan for the first time in history and the Durand Line was drawn which is now the 2,640-kilometer border between Afghanistan and Pakistan since 1947.

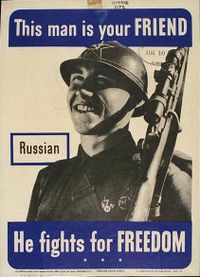

The famous great game was too played on Afghan land earlier by Great Britain and Russia in the nineteenth century and reached its climax when two superpowers Former Soviet Union and America in the twentieth century fought there.

The strategic importance of its water resources

The strategic potential of Afghanistan’s water assets are five noteworthy river basins – Kabul, Helmand, and western flowing rivers, Hari Rod and Murghab, northern flowing rivers, and Amu Darya (Oxus river) – make up the surface water assets of Afghanistan, all of which are flowing to the neighboring countries. Afghanistan is the upstream riparian to these river basins which flow into Pakistan, Iran, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Together, these river basins contribute a total of 57 BCM (billion cubic meters) of water, which will make Afghanistan the epicenter of external powers to influence their internal situation and external relations.

The strategic importance of mine and mineral resources

According to Christopher Wnuk, an American geologist, “I have never seen anything like Afghanistan. It may very well have the most mineralized place on Earth.

Further, the United States Pentagon Task Force on Business and Stability Operations dubbed the country the “Saudi Arabia of lithium”. A year later, the US Geological Survey said in a study that Afghanistan “could be considered as the world’s recognized future principal source of lithium”. By 2040, the demand for lithium could rise 40-fold as the world’s use of electric vehicles increases.

Afghanistan’s huge and largely untapped mineral wealth is also a huge attraction for international and regional players. Furthermore, the global electrification drive through the electric vehicle (EV) industry, has intensified the race between China and the US, to secure lithium, a vital component in EV batteries. Afghanistan’s estimated lithium reserves are pegged at around 2.3 million tons, making it a highly coveted prospect for countries vying for dominance in the clean energy sector.

China’s growing presence in Afghanistan’s mining sector has generated geopolitical concerns for the US and other European countries. The United States, another major player in the EV market, views China’s involvement as a strategic threat, potentially leading to heightened competition for Afghan resources. This scenario has led both countries to influence the Taliban regime, aggravating the existing tensions and realignments of inter state relations in the region. The neighboring countries like Pakistan, Iran, and Russia have therefore been drawn into the troubled waters. The exacerbating regional tensions along with several other factors could influence the future trajectory of this geopolitical landscape in the region.

The Wakhan Corridor has great Geo-strategic and geo-economic significance for Afghanistan, China, and Pakistan. The opening of this corridor has resulted in serious implications for regional and global players involved in Afghanistan, especially India and the US on the one hand, China Pakistan Iran, and Russia on the other hand.

Such competition of the major players to increase their presence and influence through their proxies and client states is turning Afghanistan again into a battlefield and the fallout of such a situation definitely will be on Pakistan including other neighboring countries.

Taliban-2 versus regional and international powers

After over four decades of unrest and turmoil in the war-ravaged Afghanistan, international and regional powers, which in the past competed for influence in Afghanistan, developed minimum consensus on the future of Afghanistan when the US-led foreign forces left the region soon after the US-Taliban Doha Agreement.

The US, China, Russia, Pakistan, Iran, and other key stakeholders pledged that the Afghan Taliban government would get recognition only after they met some conditions, of the formation of an inclusive government, respecting human and women rights and denying use of Afghan soil by terrorist groups.

For this purpose, a lot of diplomatic activity about Afghanistan — internationally and at regional level — has been underway. After the Taliban re-entered Afghanistan all those efforts have not been fruitful to make the Taliban to remove the international concerns.

Present situation in Afghanistan

Though Taliban 2.0 has brought peace to Afghanistan but the country is facing socio-economic, political military, and diplomatic chaos and uncertainty. On the internal front, there is a trust deficit between the Kabul-based Taliban leadership led by Haqqani and the Taliban leadership based in Kandahar. Hardliner factions vie for a conservative and introverted model of governance of the 1990s while moderates aspire for an inclusive approach as per the expectations of the rest of the world. The control over resource-rich regions is another reason for the internal strife of the Taliban! which has provided an opportunity to the major players to intervene in the country’s internal affairs.

Therefore, the US and Pakistan blame Afghanistan that despite Taliban commitment to the Doha agreement, it has become a hotbed of terrorist organizations like (TTP), Al-Qaeda in Subcontinent (AQIS), Eastern Turkistan Islamic Movement, Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) and Islamic State of Khorasan (IS-K). Both claim that these terrorist outfits are posing a serious threat to Pakistan, and US interests in the region. Pakistan blames TTP for carrying out cross-border attacks into Pakistan from their safe havens in Afghanistan.

A US State Department strategy paper released earlier this year cautioned US policymakers about the growing influence of its rivals — China, Russia, and Iran — in Afghanistan. The strategy paper advocated preserving the US interests and not letting its adversaries take a foothold in Afghanistan. This shows the growing tension between the two rivals pushing Afghanistan into another war theatre.

Recently, Pakistan’s Ambassador to the United Nations, conveyed to the UN Security Council: the Taliban government in Afghanistan has failed to fulfill its promises to curb cross-border terrorism by (TTP), followed by Defence Minister Khawaja Asif in an interview with Voice of America said Islamabad could strike terror havens in Afghanistan and it would not be against international law since Kabul had been “exporting” terrorism to Pakistan and the “exporters” were being harbored there by the Taliban government.

Furthermore, soon after announcement of Operation Azm-e-Istehkam against the terrorist outfits within and out side the country, Pakistan’s ambassador to the US, told Washington that “we need sophisticated small arms and communication equipment to oppose and dismantle terrorist networks.”

On the other hand, most recently the Russian president Vladimir Putin in an interview referred to the Taliban which governs Afghanistan, as an, “ally” in fight against terrorism.

Further, the impact of India, China, and Russia on Afghanistan depends on their strategic, economic, and security objectives. The trajectory of their bilateral relationship with Afghanistan will significantly shape the geopolitical dynamics in the region leading to Afghanistan toward another battlefield for the major players in the region.

How can the grime situation in the region be addressed to prevent Afghanistan from becoming a battleground again?

One thing must be clear to everyone particularly to Pakistan that Auckland manifest never worked in the distant past nor will work in the future. Afghanistan is a sovereign state that cannot be anybody’s backyard. Pakistan being an immediate neighbour must let Afghanistan be. The Afghans can decide to befriend whomever they want. Pakistan should not dictate Afghanistan in their internal and external relations, particularly about India. In case Pakistan feels threatened by TTP, it safeguards its interests from our side of the border, not through proxies. Pakistan must tell Afghanistan clearly that it will not become a frontline state again.

Major players should be competitors rather than rivals in Afghanistan. They can harvest the dividends of Afghanistan’s geo-strategic, and geo-economic resources once all of them agree to accept the sovereignty of and non interferences in the internal affairs of Afghanistan. Otherwise, as proven by the last two countries’ history, no one can take benefit of and can’t dream to serve or save their interests in the region, particularly in Afghanistan. Afghan security must be secure in an indigenous recipe to reap the benefits of economic development and regional connectivity.

Since the Taliban for the moment is now a reality in Afghanistan and no alternative is in hand, their alienation will be counterproductive, therefore, the international community, and its neighbors, particularly Pakistan should find a political settlement with the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. Engagement with the Taliban rather than pushing them to the wall will pave the way toward amicable settlements of the ongoing controversies with them.

On the other hand, the ball is in the Taliban court, they must address international concerns by improving human rights credentials, particularly concerning women’s rights particularly education and health and respect for and implementing the Doha agreement in its entirety.

Take immediate practical and sincere steps to engage Afghan leadership and civil society living within and abroad for intra-Afghan dialogue to settle constitutional, political economic reforms, institution reorganization and to provide a level playing field to Afghans for their representation in the governance system. In the Afghan context- calling a true representative Grand Jirga to decide the future course of action for a peaceful and prosperous Afghanistan. Otherwise Taliban single-handedly will not cater to internal and external challenges and the ultimate results definitely will be plunging Afghanistan into another battlefield leading to uncertainty and destruction of the country.

Sher Khan Bazai is a retired civil servant, and a former Secretary of Education in Balochistan, Pakistan. He can be reached at skbazai@hotmail.com.