The Black Death killed as many as half of all Europeans and the worst influenza pandemic claimed the lives of up to 100 million people

Both fundamentally changed the fabric of societies. Will historians say the same about Covid-19?

Charles C. Mann Published:14 Jun, 2020

In 2008, a young economist named Craig Garthwaite went looking for sick people. He found them in the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Conducted annually by the United States Census Bureau since 1957, the NHIS is the oldest and biggest continuing effort to track Americans’ health.

The survey asks a large sample of the citizenry whether they have a variety of ailments, including diabetes, kidney disorders and several types of heart disease. Garthwaite sought out a particular subset of respondents: people born between October 1918 and June 1919.

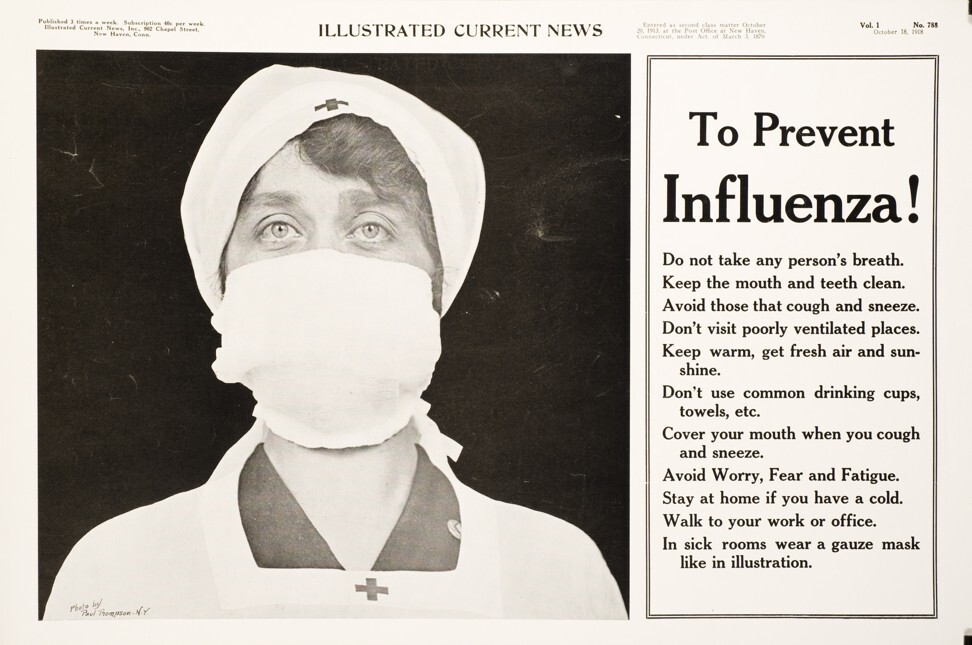

Those months were the height and immediate aftermath of the world’s worst-ever influenza pandemic. Although medical data from the time is too scant to be definitive, the first case is generally said to have been in Kansas in March 1918, as the US was stepping up its involvement in World War I.

In a flurry of wartime propaganda, American and European governments downplayed the epidemic, which helped it spread. Estimates of the final death toll range from 17 million to 100 million, depending on assumptions about the number of uncounted victims. Almost 700,000 people are thought to have died in the US – as a proportion of the population equivalent to more than two million people today.

An announcement from the Illustrated Current News dated October 18, 1918, offering tips for how to stop the spread of influenza. Photo: National Library of Medicine

Remarkably, the calamity left few visible traces in American culture. Writers Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner and F. Scott Fitzgerald saw its terrible effects first-hand, but almost never mentioned it in their work. Nor did the flu affect US policies – Congress didn’t even allocate extra money for flu research afterwards.

Just a few decades after the pandemic, American-history textbooks by the distinguished likes of Arthur M. Schlesinger Jnr, Richard Hofstadter, Henry Steele Commager and Samuel Eliot Morison said not a word about it. The first history of the 1918 flu wasn’t published until 1976. Written by the late Alfred W. Crosby, the book is called America’s Forgotten Pandemic.

Americans may have forgotten the 1918 pandemic, but it did not forget them. Garthwaite matched NHIS respondents’ health conditions to the dates when their mothers were probably exposed to the flu. Mothers who got sick in the first months of pregnancy, he discovered, had babies who, 60 or 70 years later, were unusually likely to have diabetes; mothers afflicted at the end of pregnancy tended to bear children prone to kidney disease. The middle months were associated with heart disease.

Other studies showed different consequences. Children born during the pandemic grew into shorter, poorer, less educated adults with higher rates of physical disability than one would expect. Chances are that none of Garthwaite’s flu babies ever knew about the shadow the pandemic cast over their lives. But they were living testaments to a brutal truth: pandemics – even forgotten ones – have long-term, powerful after-effects.

The distinguished historians can be forgiven for passing over this truth. Most modern people assume that our species controls its own destiny. “We’re in charge!” we think. Being modern people, historians have had trouble, as a profession, accepting that brainless packets of RNA and DNA can capsize humankind in a few weeks or months.

The convulsive social changes of the 1920s – the frenzy of financial speculation, the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, the explosion of Dionysian popular culture (jazz, flappers, speakeasies) – were easily attributed to the war, an initiative directed and conducted by humans, rather than to the blind actions of microorganisms. But the microorganisms likely killed more people than the war did. Their effects spread across the globe, emptying city streets and filling cemeteries on six continents.

Unlike the war, the flu was incomprehensible – the virus wasn’t even identified until 1931. It inspired fear of immigrants and foreigners, and anger towards the politicians who played down the virus. Like the war, influenza (and tuberculosis, which subsequently hit many flu sufferers) killed more men than women, skewing sex ratios for years afterwards. Can one be sure that the ensuing, abrupt changes in gender roles had nothing to do with the virus?

We will probably never disentangle the war and the flu. But one way to summarise the impact of the pandemic is to say that its magnitude was in the same neighbourhood as that of the “war to end all wars”.

Claims about the Black Death’s origin invoked “floods of snakes and toads, snows that melted mountains, black smoke, venomous fumes, deafening thunder, lightning bolts, hailstones and eight-legged worms that killed with their stench”. Photo: Shutterstock

Nobody can predict the consequences of today’s pandemic. But

history can tell us a little about what kind of landscape we are approaching.

Consider the Black Death. Sweeping through Europe from about 1347 to 1350, the plague killed somewhere between a third and half of all Europeans. In England, so many people died that the population didn’t climb back to its pre-plague level for almost 400 years.

With the supply of workers suddenly reduced and the demand for labour relatively unchanged, medieval landowners found themselves in a pickle: they could leave their grain to rot in the fields, or they could abandon all sense of right and wrong and raise wages enough to attract scarce workers.

In northern Italy, landlords tended to raise wages, which fostered the development of a middle class. In southern Italy, the nobility enacted decrees to prevent peasants from leaving to take better offers. Some historians date the separation in fortunes of the two halves of Italy – the rich north, the poor south – to these decisions.

When the Black Death began, the English Plantagenets were waging a long, brutal campaign to conquer France. The population losses meant such a rise in the cost of infantrymen that the whole enterprise foundered. English nobles did not occupy French chateaux. Instead they stayed home and tried to force their farmhands to accept lower wages. The result, the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, nearly toppled the English crown. King Richard II narrowly won out, but the monarchy’s ability to impose taxes, and thus its will, was permanently weakened.

An illustration by James William Edmund Doyle shows England’s King Richard II meeting rebels during the Peasants’ Revolt in 1381. Photo: Getty Images

Nobody thinks the coronavirus will kill anywhere near as many people as the Black Death did. A shortage of labour due to corpses piling up in the streets will not cause wages to rise. Even so, the new virus has been a shock to society. The plague struck a Europe that was used to widespread death from contagious disease, especially among children. The coronavirus is hitting societies that regarded deadly epidemics as things of the past, like whalebone corsets and bowler hats.

When I went to college, in the 1970s, pre-med students carried around a fat textbook co-written by the Nobel Prize-winning virologist Macfarlane Burnet. “The most likely forecast about the future of infectious disease,” it sunnily concluded, “is that it will be very dull.”

Such optimism was not exceptional. A few years later, Robert Petersdorf, a future president of the Association of American Medical Colleges, contemplated the current crop of MDs seeking certification in infectious disease and said, “I cannot conceive of a need for 309 more infectious-disease experts unless they spend their time culturing each other.”

When Aids came into the world, disease researchers reconsidered, loudly warning of new pandemics. Journalists wrote books with titles such as The Coming Plague and Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic.

But not many non-scientists took these warnings to heart. The public has not enjoyed its surprise re-entry into the world of contagion and quarantine – and this unhappiness seems likely to have consequences.

Demonstrators protest the inflated prices charged by pharmaceutical companies for Aids treatment drugs, in 1997. Photo: AFP

Scholars have long posited that the shattering of norms by the Black Death was the first step on the path that led to the Renaissance and the Reformation. Neither government nor Church could explain the plague or provide a cure, the theory goes, leading to a crisis in belief. Secular and religious leaders died just like common people – the Black Death killed the archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Bradwardine, a mere 40 days after he assumed office. People sought new sources of authority, finding them through direct personal experience with the world and with God.

To some extent, all of this is surely true. The plague came in waves, and after each wave doctors, clerics and chroniclers speculated about the causes and described the treatments they had seen deployed.

As the University of Glasgow historian Samuel Cohn Jnr has shown, the early claims about the plague’s origin invoked “floods of snakes and toads, snows that melted mountains, black smoke, venomous fumes, deafening thunder, lightning bolts, hailstones and eight-legged worms that killed with their stench”. Some writers blamed the poor: their fecundity, their improvidence, their sinfulness. Others pointed fingers at that ever-ready European bogeyman, the Jew.

Scared Europeans sought favour from the heavens, most famously taking off their clothes in groups and striking one another with whips and sticks. Images of half-nude flagellants have, since Monty Python, become a comic staple. Far less comical was the accompanying flood of anti-Semitic violence. As it spread through Germany, Switzerland, France, Spain and the Low Countries, it left behind a trail of beaten cadavers and burned homes.

Within a few decades, Cohn wrote, hysteria gave way to sober observation. Medical tracts stopped referring to conjunctions of Saturn and prescribed more earthly cures: ointments, herbs, methods for lancing boils. Even priestly writings focused on the empirical. “God was not mentioned,” Cohn noted. The massacres of Jews mostly stopped.

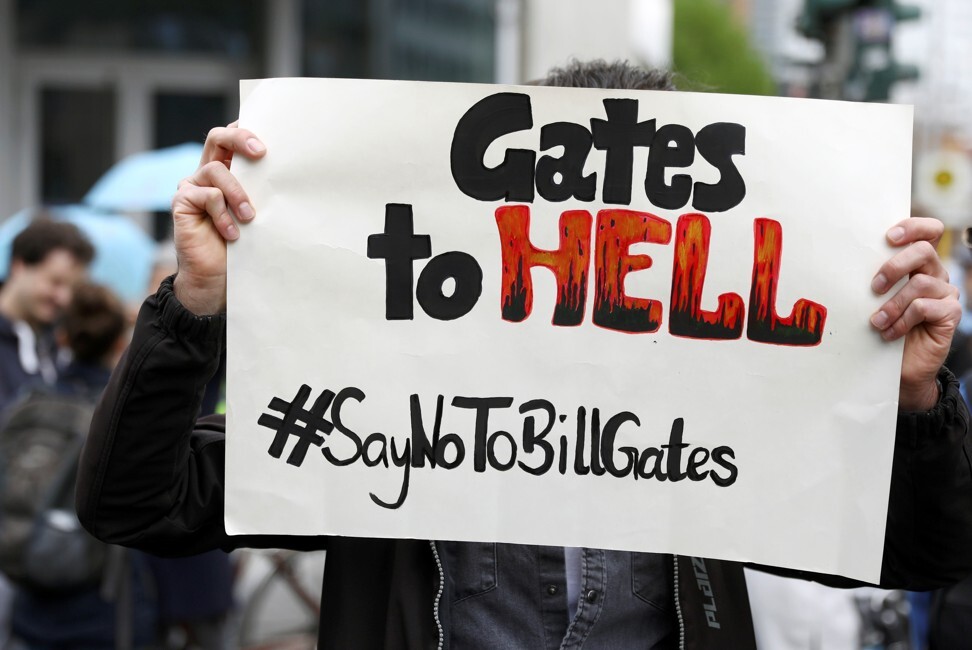

A protester holds up a placard with a message against Bill Gates, during a demonstration against the lockdown imposed to slow down the spread of the coronavirus, in Berlin, Germany, in April. Photo: Reuters

It’s easy to see this as a comforting parable of rationality winning out over the engines of rumour, prejudice and superstition, ultimately leading to the Renaissance and the Enlightenment. But the lesson seems more that humans confronting unexpected disaster engage in a contest for explanation – and the outcome can have consequences that ripple for decades or centuries.

And the contest for explanation is well under way – Donald Trump is to blame, or Barack Obama, or the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, or China, or the US military’s biowarfare experiments, or Bill Gates. Nobody has yet invoked eight-legged worms. But in our age of social media, rumour, prejudice and superstition may have even greater power than they did in the era of the Black Death.

Christopher Columbus’ journey to the Americas set off the worst demographic catastrophe in history. The indigenous societies of the Americas had few diseases – no smallpox, no measles, no cholera, no typhoid, no malaria, no bubonic plague. When Europeans imported these diseases, it was as if all the suffering and death these ailments had caused in Europe during the previous millennia were compressed into 150 years.

Up to nine-tenths of people in the Americas died. Many later European settlers believed they were coming to a vacant wilderness. But the land was not empty; it had been emptied – a world of loss encompassed in a shift of tense.

Absent the diseases, it is difficult to imagine how small groups of poorly equipped Europeans could have survived in the alien ecosystems of the Americas. “I fully support banning travel from Europe to prevent the spread of infectious disease,” the Cherokee journalist Rebecca Nagle remarked after Trump announced his plan to do this. “I just think it’s 528 years too late.”

Members of the Red Cross Motor Corps wear masks while transporting a patient in St Louis, Missouri, in October 1918. Photo: Getty Images

For Native Americans, the epidemic era lasted for centuries. Isolated Hawaii had almost no bacterial or viral disease until 1778, when the islands were “discovered” by British explorer James Cook. Islanders learned the cruel facts of contagion so rapidly that by 1806, local leaders were refusing to allow European ships to dock if they had sick people on board.

Nonetheless, Hawaii’s king and queen, Kamehameha II and Kamamalu, travelled from their clean islands to London, that cesspool of disease, arriving in May 1824. By July they were dead – measles.

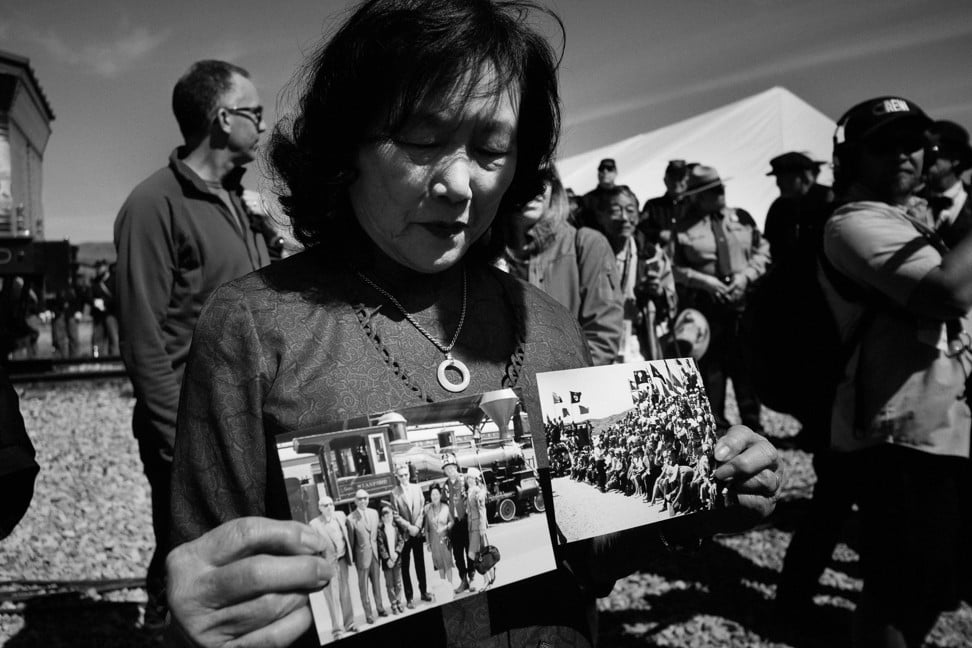

The royals had gone to Britain to negotiate an alliance against the US, which they correctly believed had designs on their nation. The monarch’s successor, 12-year-old King Kamehameha III, could not resume the talks. The results changed the islands’ destiny. Undeterred by the British Navy, the US annexed Hawaii in 1898. Historians have seldom noted the connection between measles and the presidency of Obama.

As a rule, epidemics create what researchers call a “U-shaped curve” of mortality – high death rates among the very young and very old, lower rates among working-age adults. (The 1918 flu was an exception; a disproportionate number of twenty-somethings perished.) For Native peoples, the U-shaped curve was as devastating as the sheer loss of life.

As an indigenous archaeologist once put it to me, the epidemics simultaneously robbed his nation of its future and its past: the former, by killing all the children; the latter, by killing all the elders, who were its storehouses of wisdom and experience.

I have no idea what the ultimate effects of the coronavirus will be, but I hope that they will be like those of the 2003 Sars epidemic in Hong Kong. That epidemic, which killed 299 people in the city, was stopped only by heroic communal efforts

For reasons as yet unknown, the U-shaped curve does not apply to today’s coronavirus. This virus largely (but not entirely) spares the young and targets the old. Terrible stories of it

sweeping through nursing homes reinforce this impression, especially if, like me, you’ve lost a relative in one. The result will be, among other things, a test of how much contemporary society values the elderly.

So far, the evidence suggests: not much. The speed with which pundits in the US emerged to propose that it could more easily tolerate a raft of dead oldsters than an economic contraction indicates that the reservoir of appreciation for today’s elders is not as deep as it once was. This change may reflect another: today’s old are older than the old of the past, when lifespans were shorter.

Past societies mourned the loss of collective memory caused by epidemics. Ours may not, at least at first.I have no idea what the ultimate effects of the coronavirus will be, but I hope that they will be like those of the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars) epidemic in Hong Kong. That epidemic, which killed 299 people in the city, was stopped only by heroic communal efforts.

Everyone in Hong Kong knows the city dodged a bullet. Or it seems that way when I visit. My work has taken me there, off and on, since 1992. In a city that once resounded with smokers’ coughs, people now don masks at the first sign of a cold. Omnipresent signs – in hotel lifts, on convenience-store doors, in office waiting rooms – describe how often their locations are disinfected. An amazing number of people wear surgical gloves to serve food, handle papers, even push lift buttons.

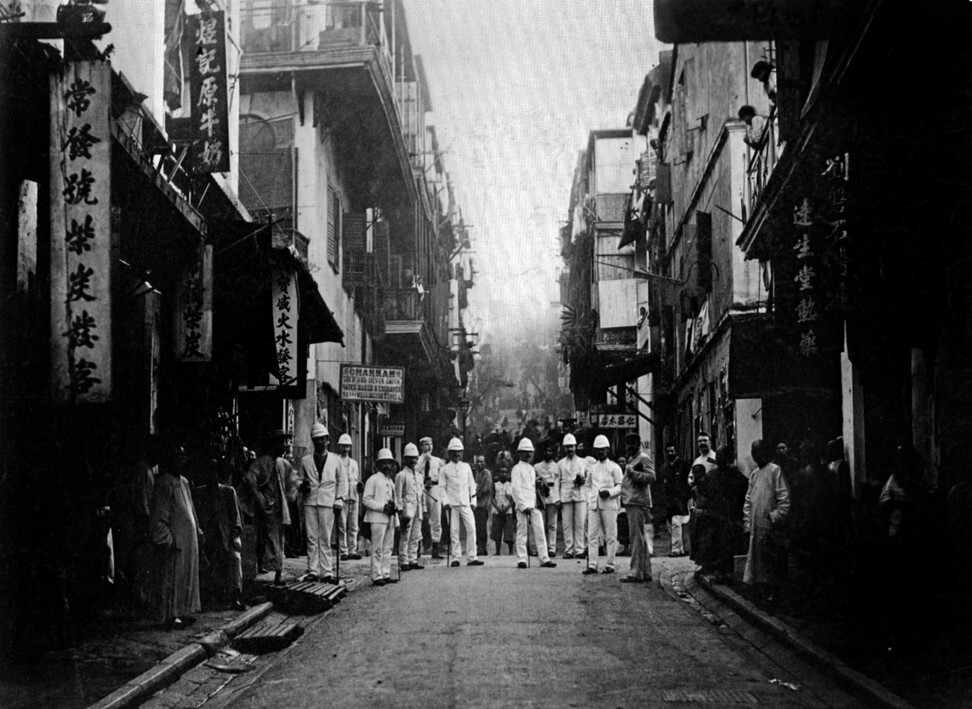

Hongkongers in Central during the 2003 Sars outbreak. Photo: AFP

These measures may suggest a community in the grip of fear. But the masks and signs and gloves seem more like the “victory gardens” outside homes during World War II – cheerful public notices of people doing their part. Most important, Hong Kong may have contained Covid-19 faster than any other place in the world.

I was there during last autumn’s protests. At one point, I found myself near a university at the centre of the unrest. Almost nobody was outside and the shops were closed. There was a lot of debris and smoke. As I stood there, befuddled, a man ran out of a convenience store and pulled me inside. “The police are coming,” he said. “Very dangerous!”

Inside was a cross section of Hong Kong citizens – young and old, trainers and salaryman shoes, quite a few in makeshift masks. I thanked the proprietor for rescuing me from what could have been an unpleasant encounter. “We are all here together,” someone said.

Later it occurred to me that a possible legacy of Hong Kong’s success with Sars is that its citizens seem to put more faith in collective action than they used to. I’ve met plenty of Hongkongers who believe that the members of their community can work together for the greater good – as they did in suppressing Sars and will, with luck, keep doing with Covid-19. It’s probably naive of me to hope that containing the coronavirus would impart some of the same faith elsewhere, but I do anyway.

Financial support for this article was provided by the HHMI Department of Science Education.

Text: The Atlantic Magazine

Charles C. Mann is an American journalist and author, specialising in scientific topics.

‘If you catch it, don't spread it to others’, 1949 flu advice still applies to coronavirus pandemic