How disease has fed on China’s progress – shift from nomadic hunters to farming communities sowed the seeds for millennia of sickness

From malarial neolithic settlements on the Yellow River plain to the plague-ravaged Mongols and today’s host-jumping pathogens, disease has long helped to shape China

Thomas Bird Published: 24 May, 2020

In 1999, while most people were anticipating what the new millennium might bring, American academic Jared Diamond cast his gaze back 10,000 years to question whether the agricultural revolution that had germinated settled society had really been such a great leap forward.

Writing in Discover Magazine, Diamond contended, “With agriculture came the gross social and sexual inequality, the disease and despotism, that curse our existence.” Significantly, epidemics that “couldn’t take hold when populations were scattered in small bands that constantly shifted camp” spread only after humans began to grow crops and raise chickens. “Tuberculosis and diarrheal disease had to await the rise of farming; measles and bubonic plague the appearance of large cities.”

Yet for the Chinese, the idea that agriculture was the wellspring of civilisation is seldom, if ever questioned.

From the revolutionaries that settled the Yellow River valley thousands of years ago, Chinese history is often framed with Long March gallantry, leading step by step from paddy field to palatial shopping centre. Chinese civilisation, the story goes, outlasted all its rivals and triumphed over the vagaries of nature, stoically enduring episodes of turmoil to arrive at the current age of abundance. It is a tale of great and ongoing struggle, soaked in blood, sweat and jingoism.

Since AD200-250, traditional Chinese medicine has harnessed all aspects of life, from food to sex. (Illustration from G.N. Wright’s 1843 book, China, In a Series of Views, Displaying the Scenery, Architecture, and Social Habits, of That Ancient Empire.) Photo: Getty Images

But what if it was the millet first planted by China’s neolithic ancestors that sowed the seeds for centuries of untold misery?

Like those of ancient Greece, China’s origin myths were created in hindsight and reflect a preordained greatness to come. Shennong, the god of agriculture, taught the Chinese to farm, while his successor, Huangdi, the Yellow Emperor, symbolically battled his rival Chiyou for control of the hazardous Yellow River, from whose surroundings would grow the very idea of China as we know it.

As far back as records go, we know the Yellow River was a capricious mistress. Its lethal capacity to shift course without warning, causing massive floods accompanied by famine and disease, prompted author Philip Ball to remark in The Water Kingdom (2016), “it’s hard to imagine how anyone, let alone millions, endured it routinely”.

The river’s propensity for disaster continued until the modern era. In 1887, as many as 2.5 million people were killed by floods or related diseases such as typhoid. And yet, along its muddy banks in about 7500BC – at roughly the same time the Fertile Crescent was being settled in the Middle East – neolithic societies decided to make a go of it as farmers. By 2070BC, a state had emerged: the mysterious Xia people.

We don’t know much about Xia society but evidence suggests bean curd, fruits such as oranges and peaches, and animal husbandry were established means of food production for the pioneer Chinese state. But living in settlements meant the Xia – followed by the Shang and Zhou dynasties – unearthed “snakes” and “dragons” from the Yellow River plain, or what Mary Dobson in Murderous Contagion (2014) dubs “ancient maladies” like malaria and schistosomiasis.

The latter is caused by parasitic flatworms that “became a significant human infection in river valleys such as the Euphrates, the Nile in Egypt and the Yellow (Huang He) River in China, when people began to settle, farm and irrigate the land”.

Living in proximity to domesticated animals put people in range of other invisible enemies, as Yuval Noah Harari outlines in Sapiens (2011): “Most of the infectious diseases that have plagued agricultural and industrial societies (such as smallpox, measles and tuberculosis) originated in domesticated animals and were transferred to humans only after the Agricultural Revolution.”

Evidence for this can be found in the 3,000-year-old Chinese character jia, meaning “home” and “family”, which is represented by a pig in a house. A typical Shang dynasty household would have lived cheek-by-jowl with their livestock, oblivious to the dangers this arrangement posed.

A 1907 illustration in Paris’ Le Petit Journal shows cholera victims in China and government officials being mobbed by starving people. Photo: Getty Images

A host of “lifestyle diseases” afflicted the Chinese, too. From sunrise to sunset, toiling farmers were weakened by “slipped discs, arthritis and hernias”, writes Harari, ailments unknown to hunter-gatherers who “spent their time in more stimulating and varied ways, and were less in danger of starvation and disease”. Nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples, such as the Xiongnu, Toba, Khitan and Mongols – to name but a few “barbarian” peoples given to pillaging China – would know little of such maladies.

As the Chinese had committed themselves to the land, they couldn’t abandon their pastures and ride off into the sunset, as their enemies invariably did. So while rationalist culture and philosophical debate evolved in the open city of Athens, on the other side of the world, the Chinese began to wall themselves in, a mode of defence that was well under way by the latter half the Eastern Zhou dynasty (770-256BC).

Every siheyuan, or quadrangle courtyard house, would have its “garden” or social space located inside; every village, town and city would be ringed with rammed earth or stone. Even the imperial frontier would be demarcated by the Great Wall, the earliest version of which dates back to 300BC and the Zhao State, according to wall historian William Lindesay. Only in the 20th century did China begin to demolish its city ramparts.

These barriers helped slow the progress of China’s external enemies, but made the enemy within harder to contain. As Harari writes, “most people in agricultural and industrial societies lived in dense, unhygienic permanent settlements – ideal hotbeds of disease”. Thus China was forced to fight a protracted campaign on two fronts, against invading steppe peoples and the baibing (100 diseases): both microbe and marauding Mongols could become a potential regime changer if left unchecked.

The shift from nomadic hunters to settled farming communities sowed the seeds for millennia of disease. Photo: Getty Images

To confront wily tribes, China was able to make war, Diamond writes: “Farming could support many more people than hunting, albeit with a poorer quality of life […] a hundred malnourished farmers can still outfight one healthy hunter.” So the Chinese played the numbers game, unaware the imperial granaries hid a Malthusian trap – unchecked population growth versus a static food supply.

As early as 1300BC, Anyang, in Henan province, was the biggest city in the world. By the Tang dynasty (AD618-907) Chang’an (modern Xian) was home to more than a million people. Han China (202BC-AD220) was more populous than its Western contemporary, the Roman Empire.

Running low on space, farmers “crept over the face of China like a skin rash”, as travel writer Bruce Chatwin put it, settling further and further from their Yellow River homeland, and often within range of steppe nomads or southern barbarians – the Baiyue, meaning 100 yue, or peoples. Though famine, disease and war occasionally levelled the population, a period of peace or a new innovation, such as the introduction of counter-cyclical New World crops like corn and potatoes during the Qing dynasty (1644-1912), saw numbers rise over time.

Just as Europeans sent their excess population to the colonies of the New World, the Chinese, too, were forced to “colonise” fresh pastures. They sailed across the straits to Taiwan, intruded on the Tibetan plateau, crept northeast into Manchuria and southwest into the tribal lands of Yunnan and Guizhou, displacing indigenous peoples and forging the ethnic and political tensions of today. But unlike Europeans, who took lethal germs to the Americas, the Chinese often found themselves contracting new indigenous diseases, especially in the tropical south.

The Mawangdui medical texts demonstrate the Han aristocrats’ obsession with preserving health, avoiding disease, and living life to the fullestRuth Rogaski, scholar

Agriculture may not have brought a better life for the average Zhou, but it did bring surplus, which as Diamond points out, fed a class society. China’s pampered elites congregated in great urban centres – Chang’an, Luoyang and, later, Beijing – from where they sought to manage their expansive realm. They imposed strict rules on their subjects, such as

the nightly imperial curfew.

But these security measures only helped make Chinese settlements hotbeds for “crowd diseases” such as smallpox and measles. Besides the poisoning and assassinations that were the stuff of court politics, disease remained an emperor’s biggest threat. By the time of the Han dynasty, the literate Chinese had amassed the greatest canon of medical texts in the world.

“Among the earliest extant medical texts are those recovered from the Mawangdui tomb (sealed 168BC) in present-day Hunan,” writes scholar Ruth Rogaski in her 2014 book Hygienic Modernity. “The Mawangdui medical texts demonstrate the Han aristocrats’ obsession with preserving health, avoiding disease, and living life to the fullest.” The text reads like the advice of a modern health guru, describing, “sexual practices, dietetic regimens, movements and medicines designed to nurture vital forces and ensure the proper flow of qi within the body”.

The Han period, now considered an early “scientific golden era”, also produced a number of famous doctors. Some are revered to this day, such as Hua Tuo, the first to use a general anaesthetic.

The Chinese gave fantastically descriptive names to the “pestilent qi” that afflicted them: “toad fever”, for example, caused the abdomen to swell, and “crab fever” caused small red bumps on the throat.

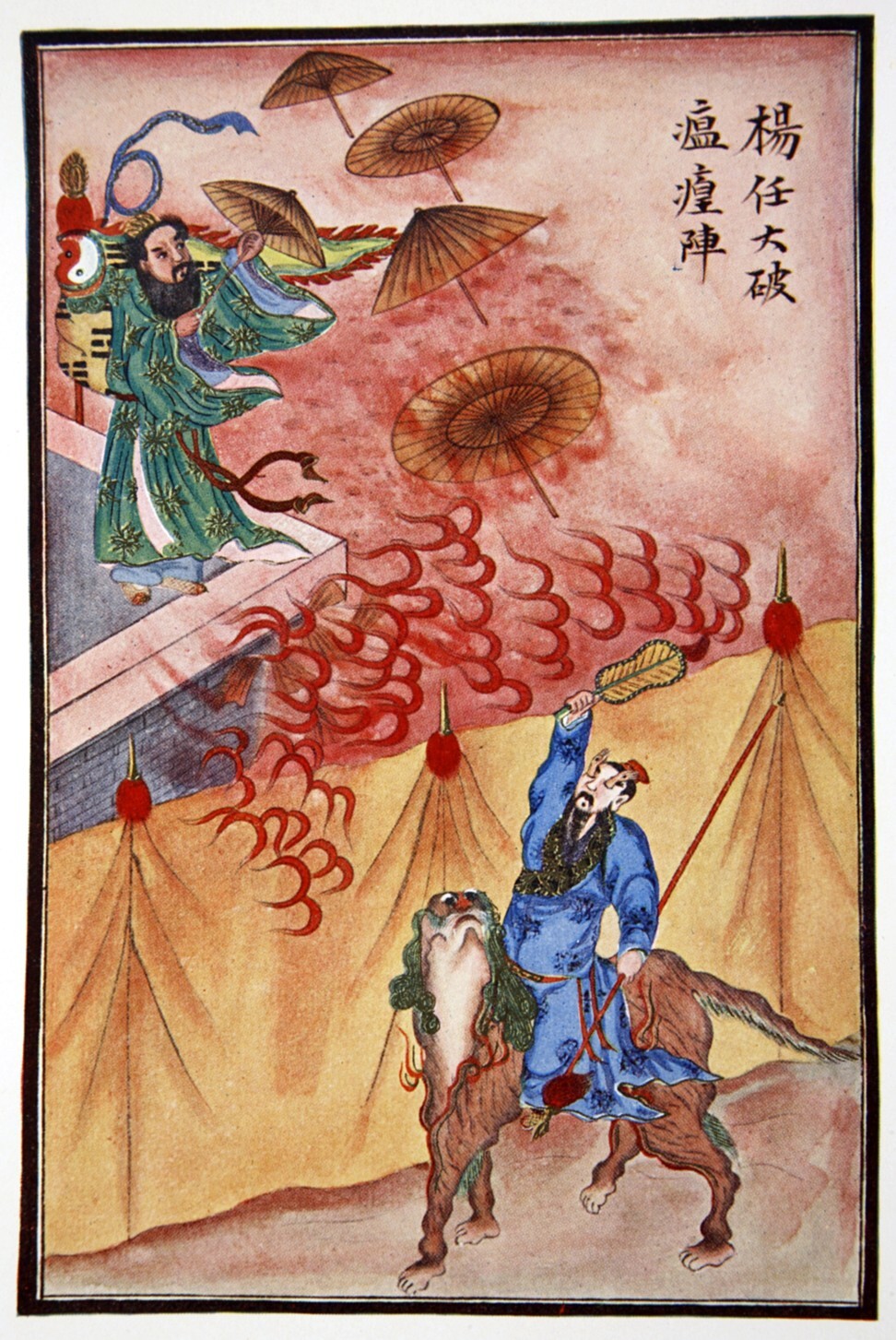

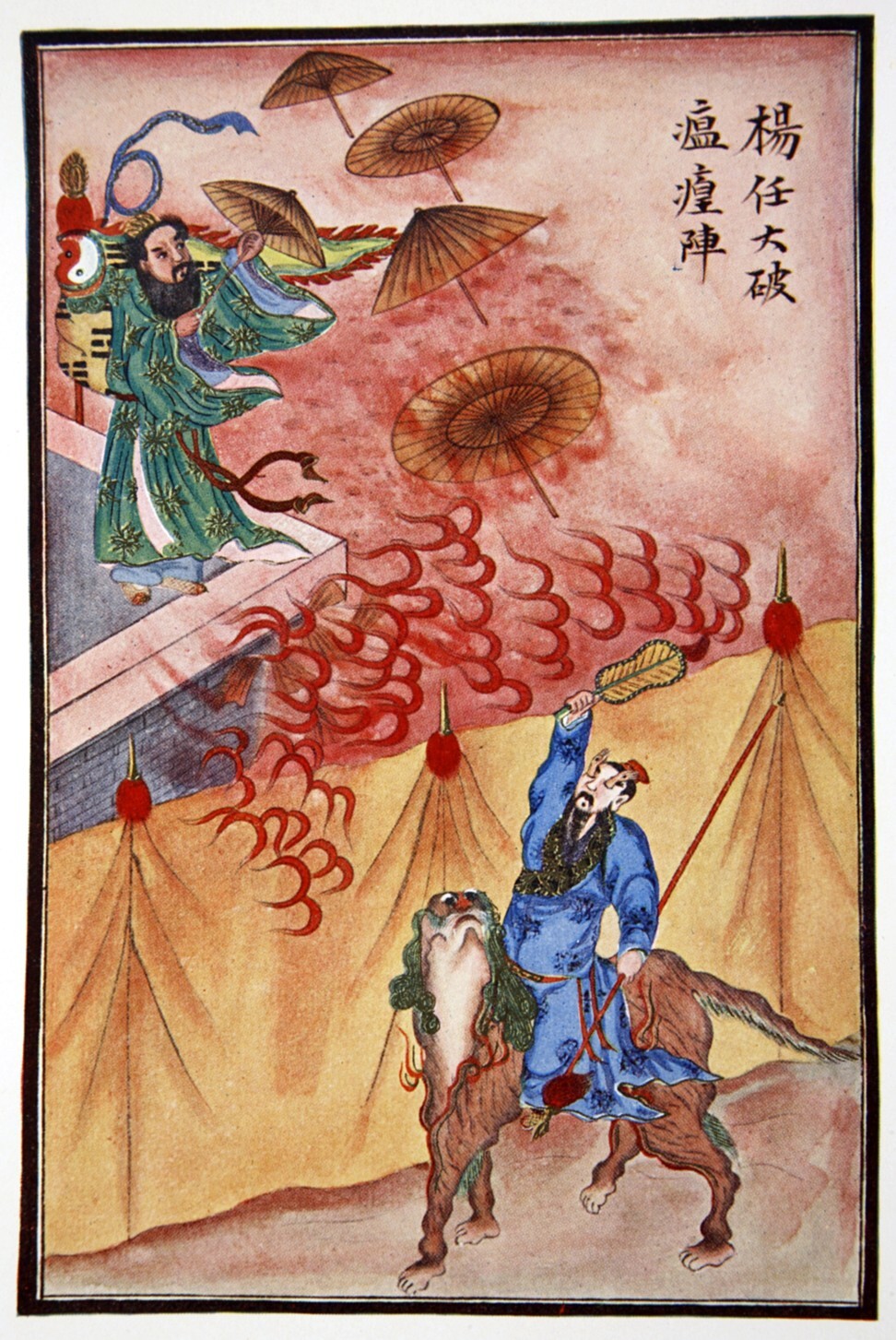

In a 1922 illustration from Myths and Legends of China, by Edward T.C. Lerner, plague-disseminating umbrellas are defeated by the wave of a magic fan. Photo: Getty Images

With a vocabulary born of Taoism, which advocates harmony with the natural order of the cosmos, traditional Chinese medicine brought together myriad means of “guarding life” (weisheng) and “nurturing life” (yansheng), including meditation and martial arts, sex and sexual abstinence, tea and food, cosmology and herbology. All aspects of life were marshalled to the cause of weisheng zhi dao, the way of guarding life.

Medical quests are a recurring theme in Chinese history, most famously perhaps the unifying emperor Qin Shihuang’s hunt for the elixir of immortality, which saw him order a sea expedition to mythical Penglai Mountain to find a 1,000-year-old magician who held the secrets of longevity. The ship never returned and Qin died two years later, after swallowing mercury pills given to him by the court doctor.

The legend lingered for a millennia and, in 1220, Genghis Khan, having already conquered much of northern China and Eurasia, summoned Taoist master Qiu Chuji from Shandong to his royal camp in present-day Uzbekistan to ask him for the medicine of immortality. Although Qiu did not have the elixir the Great Khan sought, Rogaski writes, “The Daoist master [offered]a regimen that could strengthen the body’s resistance to illness.”

The advice included “a diet harmonised with the seasons” as well as “quiet meditation” and warned against the “dangers of sex”. That pearl of wisdom was conveniently ignored by a man for whom harems, concubines and the rape of enemy wives was the norm. According to an international genetic study published in 2003, the Great Khan may have as many as 16 million descendants living today in the lands of the former Mongol empire.

The hunt for Genghis Khan’s tomb on ‘Mountain X’

20 Jul 2018

But 50 years later, the Mongol Yuan dynasty would be in trouble. The Mongols adapted poorly to sedentary life, preferring to live in tents rather than the palaces of Dadu (Beijing). Despite Kublai Khan’s Confucian pretensions, he continued to banquet like a Mongol, but without hunting he grew from the “well-formed” figure Marco Polo met to an obese ruler afflicted by severe rheumatism and gout. The Mongol aristocrats squabbled, their mastery of siege warfare no apprenticeship for Chinese statecraft and they were resented by the majority Han Chinese.

But what really plagued Yuan China was, well, plague. We don’t know if the virulent strain of bubonic plague that ravaged China in the 1330s was the Black Death that crept into Europe in the 1340s and killed two-thirds of the population, though a similarly horrific mortality rate in China suggests it was.

Fourteenth century Europeans often called it “the pestilence from the East”. Given the timing of the disease, it was likely introduced to China via Himalayan horsemen, then travelled down the recently opened Silk Road. Hubei province lost 90 per cent of its population, according to historian Jonathan Fenby. Plague and other epidemics saw the population decline under the Mongols from an estimated 110 million to 85 million by the time they lost power, in 1368, after a series of popular uprisings against China’s ancient foes: nomads and disease.

The early Ming dynasty that followed was a prosperous period epitomised by the voyages of

Admiral Zheng He, who famously sailed the South China Sea and Indian Ocean projecting Chinese state power to the known world. But as during any stable epoch, the population spiked, a rise accompanied by frequent outbreaks of measles and smallpox.

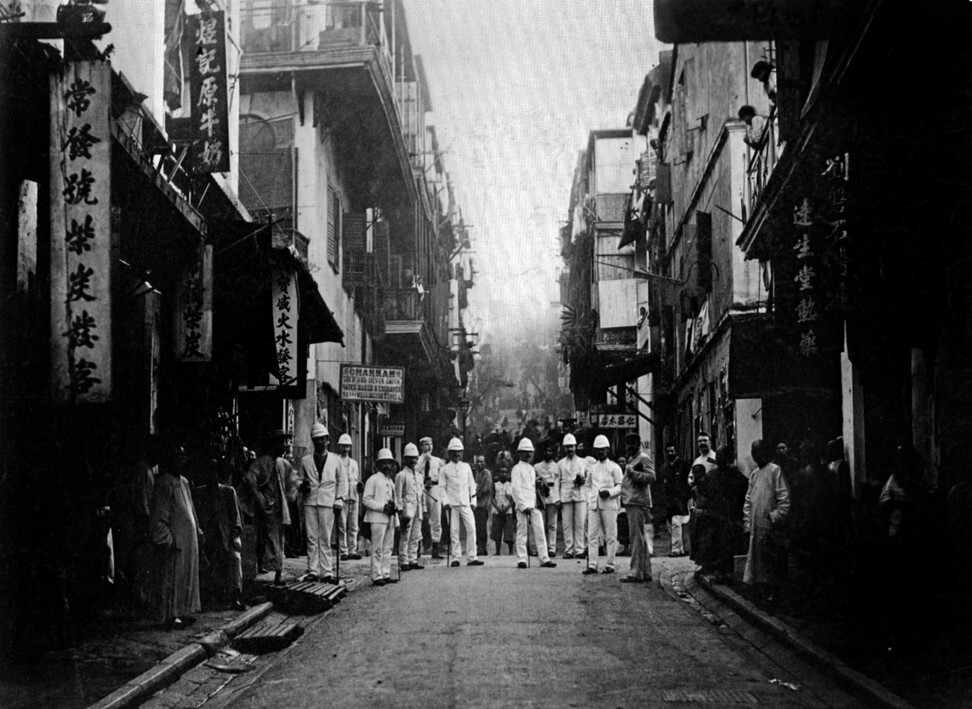

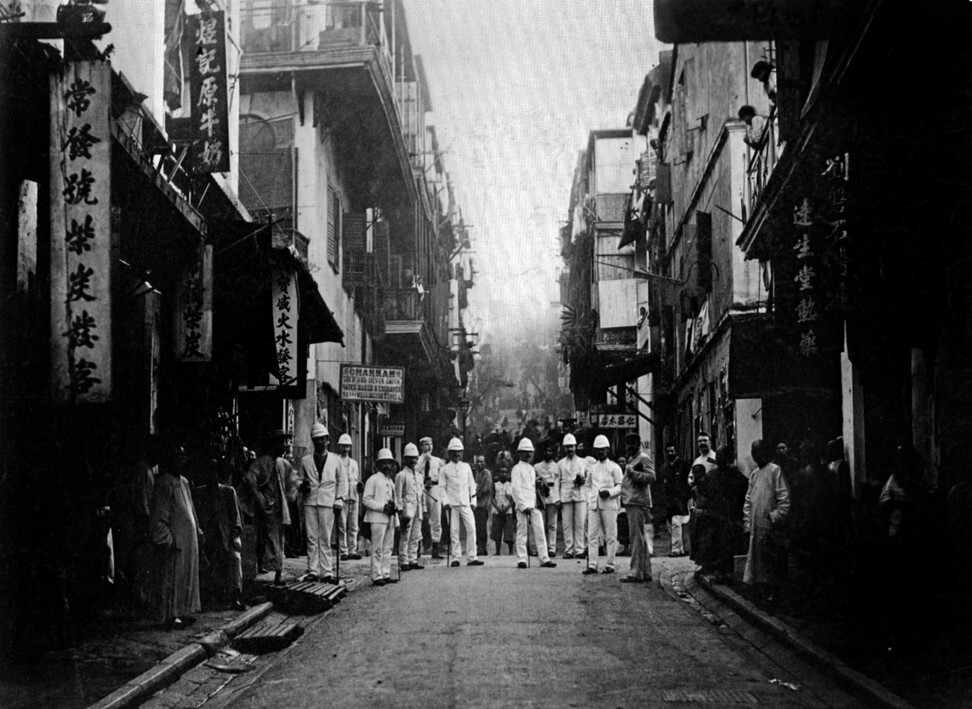

Plague inspectors in Hong Kong in August 1890; the disease broke out in Western district and continued sporadically until the 1920s. Photo: Getty Images

“In 1407, 78,400 died from epidemics in Jiangsu and Fujian provinces alone,” writes Louise Levathes in When China Ruled the Seas (1994). And so Zheng’s fourth expedition had clandestine motives, namely to collect medicinal herbs and cures from the markets of Sumatra, Malacca and Ceylon, and take them back to China to help heal the sick.

When the Portuguese sailed into the same ports less than a century later, they heard stories of the great Chinese fleet that had preceded them. When they arrived in South China, in 1513, the Celestial Kingdom appeared to live up to its lofty reputation. Accounts from the time credit the Chinese with being civil and clean. Adventurer Galeote Pereira wrote, “They feed with two sticks, refraining from touching their meat with their hands, even as we do with forks, for which respect, they less do need any tablecloths. Neither is the nation only civil at meat, but also in conversation and in courtesy they seem to exceed all.”

Such praise helped provoke a mania for chinoiserie in 17th century Europe. Commodities such as fine tea, porcelain and silks helped engender an imagined oriental heaven, free from the suffering of disease-ridden Europe.

We don’t know much about Xia society but evidence suggests bean curd, fruits such as oranges and peaches, and animal husbandry were established means of food production for the pioneer Chinese state. But living in settlements meant the Xia – followed by the Shang and Zhou dynasties – unearthed “snakes” and “dragons” from the Yellow River plain, or what Mary Dobson in Murderous Contagion (2014) dubs “ancient maladies” like malaria and schistosomiasis.

The latter is caused by parasitic flatworms that “became a significant human infection in river valleys such as the Euphrates, the Nile in Egypt and the Yellow (Huang He) River in China, when people began to settle, farm and irrigate the land”.

Living in proximity to domesticated animals put people in range of other invisible enemies, as Yuval Noah Harari outlines in Sapiens (2011): “Most of the infectious diseases that have plagued agricultural and industrial societies (such as smallpox, measles and tuberculosis) originated in domesticated animals and were transferred to humans only after the Agricultural Revolution.”

Evidence for this can be found in the 3,000-year-old Chinese character jia, meaning “home” and “family”, which is represented by a pig in a house. A typical Shang dynasty household would have lived cheek-by-jowl with their livestock, oblivious to the dangers this arrangement posed.

A 1907 illustration in Paris’ Le Petit Journal shows cholera victims in China and government officials being mobbed by starving people. Photo: Getty Images

A host of “lifestyle diseases” afflicted the Chinese, too. From sunrise to sunset, toiling farmers were weakened by “slipped discs, arthritis and hernias”, writes Harari, ailments unknown to hunter-gatherers who “spent their time in more stimulating and varied ways, and were less in danger of starvation and disease”. Nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples, such as the Xiongnu, Toba, Khitan and Mongols – to name but a few “barbarian” peoples given to pillaging China – would know little of such maladies.

As the Chinese had committed themselves to the land, they couldn’t abandon their pastures and ride off into the sunset, as their enemies invariably did. So while rationalist culture and philosophical debate evolved in the open city of Athens, on the other side of the world, the Chinese began to wall themselves in, a mode of defence that was well under way by the latter half the Eastern Zhou dynasty (770-256BC).

Every siheyuan, or quadrangle courtyard house, would have its “garden” or social space located inside; every village, town and city would be ringed with rammed earth or stone. Even the imperial frontier would be demarcated by the Great Wall, the earliest version of which dates back to 300BC and the Zhao State, according to wall historian William Lindesay. Only in the 20th century did China begin to demolish its city ramparts.

These barriers helped slow the progress of China’s external enemies, but made the enemy within harder to contain. As Harari writes, “most people in agricultural and industrial societies lived in dense, unhygienic permanent settlements – ideal hotbeds of disease”. Thus China was forced to fight a protracted campaign on two fronts, against invading steppe peoples and the baibing (100 diseases): both microbe and marauding Mongols could become a potential regime changer if left unchecked.

The shift from nomadic hunters to settled farming communities sowed the seeds for millennia of disease. Photo: Getty Images

To confront wily tribes, China was able to make war, Diamond writes: “Farming could support many more people than hunting, albeit with a poorer quality of life […] a hundred malnourished farmers can still outfight one healthy hunter.” So the Chinese played the numbers game, unaware the imperial granaries hid a Malthusian trap – unchecked population growth versus a static food supply.

As early as 1300BC, Anyang, in Henan province, was the biggest city in the world. By the Tang dynasty (AD618-907) Chang’an (modern Xian) was home to more than a million people. Han China (202BC-AD220) was more populous than its Western contemporary, the Roman Empire.

Running low on space, farmers “crept over the face of China like a skin rash”, as travel writer Bruce Chatwin put it, settling further and further from their Yellow River homeland, and often within range of steppe nomads or southern barbarians – the Baiyue, meaning 100 yue, or peoples. Though famine, disease and war occasionally levelled the population, a period of peace or a new innovation, such as the introduction of counter-cyclical New World crops like corn and potatoes during the Qing dynasty (1644-1912), saw numbers rise over time.

Just as Europeans sent their excess population to the colonies of the New World, the Chinese, too, were forced to “colonise” fresh pastures. They sailed across the straits to Taiwan, intruded on the Tibetan plateau, crept northeast into Manchuria and southwest into the tribal lands of Yunnan and Guizhou, displacing indigenous peoples and forging the ethnic and political tensions of today. But unlike Europeans, who took lethal germs to the Americas, the Chinese often found themselves contracting new indigenous diseases, especially in the tropical south.

The Mawangdui medical texts demonstrate the Han aristocrats’ obsession with preserving health, avoiding disease, and living life to the fullestRuth Rogaski, scholar

Agriculture may not have brought a better life for the average Zhou, but it did bring surplus, which as Diamond points out, fed a class society. China’s pampered elites congregated in great urban centres – Chang’an, Luoyang and, later, Beijing – from where they sought to manage their expansive realm. They imposed strict rules on their subjects, such as

the nightly imperial curfew.

But these security measures only helped make Chinese settlements hotbeds for “crowd diseases” such as smallpox and measles. Besides the poisoning and assassinations that were the stuff of court politics, disease remained an emperor’s biggest threat. By the time of the Han dynasty, the literate Chinese had amassed the greatest canon of medical texts in the world.

“Among the earliest extant medical texts are those recovered from the Mawangdui tomb (sealed 168BC) in present-day Hunan,” writes scholar Ruth Rogaski in her 2014 book Hygienic Modernity. “The Mawangdui medical texts demonstrate the Han aristocrats’ obsession with preserving health, avoiding disease, and living life to the fullest.” The text reads like the advice of a modern health guru, describing, “sexual practices, dietetic regimens, movements and medicines designed to nurture vital forces and ensure the proper flow of qi within the body”.

The Han period, now considered an early “scientific golden era”, also produced a number of famous doctors. Some are revered to this day, such as Hua Tuo, the first to use a general anaesthetic.

The Chinese gave fantastically descriptive names to the “pestilent qi” that afflicted them: “toad fever”, for example, caused the abdomen to swell, and “crab fever” caused small red bumps on the throat.

In a 1922 illustration from Myths and Legends of China, by Edward T.C. Lerner, plague-disseminating umbrellas are defeated by the wave of a magic fan. Photo: Getty Images

With a vocabulary born of Taoism, which advocates harmony with the natural order of the cosmos, traditional Chinese medicine brought together myriad means of “guarding life” (weisheng) and “nurturing life” (yansheng), including meditation and martial arts, sex and sexual abstinence, tea and food, cosmology and herbology. All aspects of life were marshalled to the cause of weisheng zhi dao, the way of guarding life.

Medical quests are a recurring theme in Chinese history, most famously perhaps the unifying emperor Qin Shihuang’s hunt for the elixir of immortality, which saw him order a sea expedition to mythical Penglai Mountain to find a 1,000-year-old magician who held the secrets of longevity. The ship never returned and Qin died two years later, after swallowing mercury pills given to him by the court doctor.

The legend lingered for a millennia and, in 1220, Genghis Khan, having already conquered much of northern China and Eurasia, summoned Taoist master Qiu Chuji from Shandong to his royal camp in present-day Uzbekistan to ask him for the medicine of immortality. Although Qiu did not have the elixir the Great Khan sought, Rogaski writes, “The Daoist master [offered]a regimen that could strengthen the body’s resistance to illness.”

The advice included “a diet harmonised with the seasons” as well as “quiet meditation” and warned against the “dangers of sex”. That pearl of wisdom was conveniently ignored by a man for whom harems, concubines and the rape of enemy wives was the norm. According to an international genetic study published in 2003, the Great Khan may have as many as 16 million descendants living today in the lands of the former Mongol empire.

The hunt for Genghis Khan’s tomb on ‘Mountain X’

20 Jul 2018

But 50 years later, the Mongol Yuan dynasty would be in trouble. The Mongols adapted poorly to sedentary life, preferring to live in tents rather than the palaces of Dadu (Beijing). Despite Kublai Khan’s Confucian pretensions, he continued to banquet like a Mongol, but without hunting he grew from the “well-formed” figure Marco Polo met to an obese ruler afflicted by severe rheumatism and gout. The Mongol aristocrats squabbled, their mastery of siege warfare no apprenticeship for Chinese statecraft and they were resented by the majority Han Chinese.

But what really plagued Yuan China was, well, plague. We don’t know if the virulent strain of bubonic plague that ravaged China in the 1330s was the Black Death that crept into Europe in the 1340s and killed two-thirds of the population, though a similarly horrific mortality rate in China suggests it was.

Fourteenth century Europeans often called it “the pestilence from the East”. Given the timing of the disease, it was likely introduced to China via Himalayan horsemen, then travelled down the recently opened Silk Road. Hubei province lost 90 per cent of its population, according to historian Jonathan Fenby. Plague and other epidemics saw the population decline under the Mongols from an estimated 110 million to 85 million by the time they lost power, in 1368, after a series of popular uprisings against China’s ancient foes: nomads and disease.

The early Ming dynasty that followed was a prosperous period epitomised by the voyages of

Admiral Zheng He, who famously sailed the South China Sea and Indian Ocean projecting Chinese state power to the known world. But as during any stable epoch, the population spiked, a rise accompanied by frequent outbreaks of measles and smallpox.

Plague inspectors in Hong Kong in August 1890; the disease broke out in Western district and continued sporadically until the 1920s. Photo: Getty Images

“In 1407, 78,400 died from epidemics in Jiangsu and Fujian provinces alone,” writes Louise Levathes in When China Ruled the Seas (1994). And so Zheng’s fourth expedition had clandestine motives, namely to collect medicinal herbs and cures from the markets of Sumatra, Malacca and Ceylon, and take them back to China to help heal the sick.

When the Portuguese sailed into the same ports less than a century later, they heard stories of the great Chinese fleet that had preceded them. When they arrived in South China, in 1513, the Celestial Kingdom appeared to live up to its lofty reputation. Accounts from the time credit the Chinese with being civil and clean. Adventurer Galeote Pereira wrote, “They feed with two sticks, refraining from touching their meat with their hands, even as we do with forks, for which respect, they less do need any tablecloths. Neither is the nation only civil at meat, but also in conversation and in courtesy they seem to exceed all.”

Such praise helped provoke a mania for chinoiserie in 17th century Europe. Commodities such as fine tea, porcelain and silks helped engender an imagined oriental heaven, free from the suffering of disease-ridden Europe.

When Europeans finally did intrude on China, in the wake of British gunboats at the conclusion of the first opium war, in 1842, their elevated opinion of the Chinese had turned to arrogant contempt. They regarded the Qing empire as being home to godless heathens, dirty and diseased, and “in need of foreign salvation and administration”, as Beijing-based historian Jeremiah Jenne explains the pretext for carving up China.

Superstition was so rife in China that fighters in the 1899-1901 Boxer Rebellion relied on amulets for protection. Photo: Getty Images

The imperial interlopers established sheltered communities, often on islands, away from the “natives” who spat and smoked opium, much of which was imported by Europeans. Accounts at the time express revulsion for the smells and “miasmas” endemic to China’s overcrowded cities. Cholera outbreaks were frequent and misery was a virtue to be endured.

Superstition was so rife in China that fighters in the 1899-1901 Boxer Rebellion relied on amulets for protection. Photo: Getty Images

The imperial interlopers established sheltered communities, often on islands, away from the “natives” who spat and smoked opium, much of which was imported by Europeans. Accounts at the time express revulsion for the smells and “miasmas” endemic to China’s overcrowded cities. Cholera outbreaks were frequent and misery was a virtue to be endured.

The Chinese appeared so burdened by history as to be blind to the light of modernity – slaves to injudicious Manchu overlords and superstitious beyond comprehension. When sick, they prayed at the Medicine King Temple or drank bitter herbal concoctions. They believed sacred amulets could protect the wearer from harm, as evidenced during the catastrophic Boxer Rebellion of 1899-1901, when northern Chinese peasants rose up against Christian missionaries and Western merchants, leading to their wholesale massacre and the sacking of Beijing’s Summer Palace by British and French soldiers.

Feeding the prejudice, two outbreaks of plague in late-Qing China rocked the world. What the Chinese called the “rat epidemic” emerged in 1855 in Yunnan province, where the Han Chinese had been moving in great numbers to mine tin. Ethnic tensions between minority peoples, especially Hui Muslims, and the newly arrived Han, erupted into rebellion. The Qing government sent troops to quash the revolt and they returned infected with the disease. Within weeks, it had killed 60,000 people in Guangzhou, then in 1894, it spread to Hong Kong, Britain’s new global entrepôt.

“From Hong Kong steamships carried the plague bacilli to all the major seaports in the world,” writes Carol Benedict in her 1996 book, Bubonic Plague in Nineteenth-Century China. “In most cases, the disease did not spread further inland, but in India plague claimed some 6,000,000 victims between 1898 and 1908.”

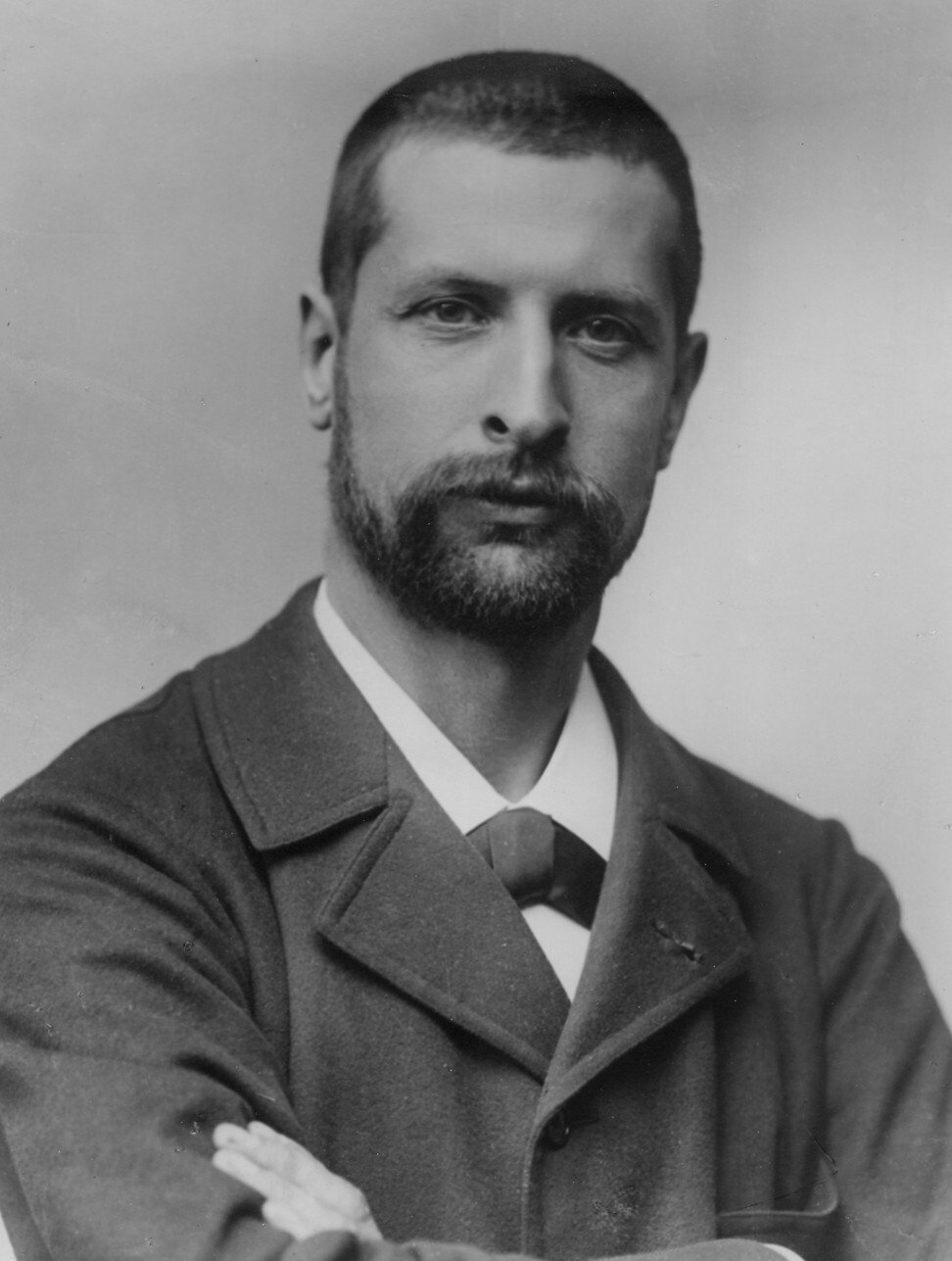

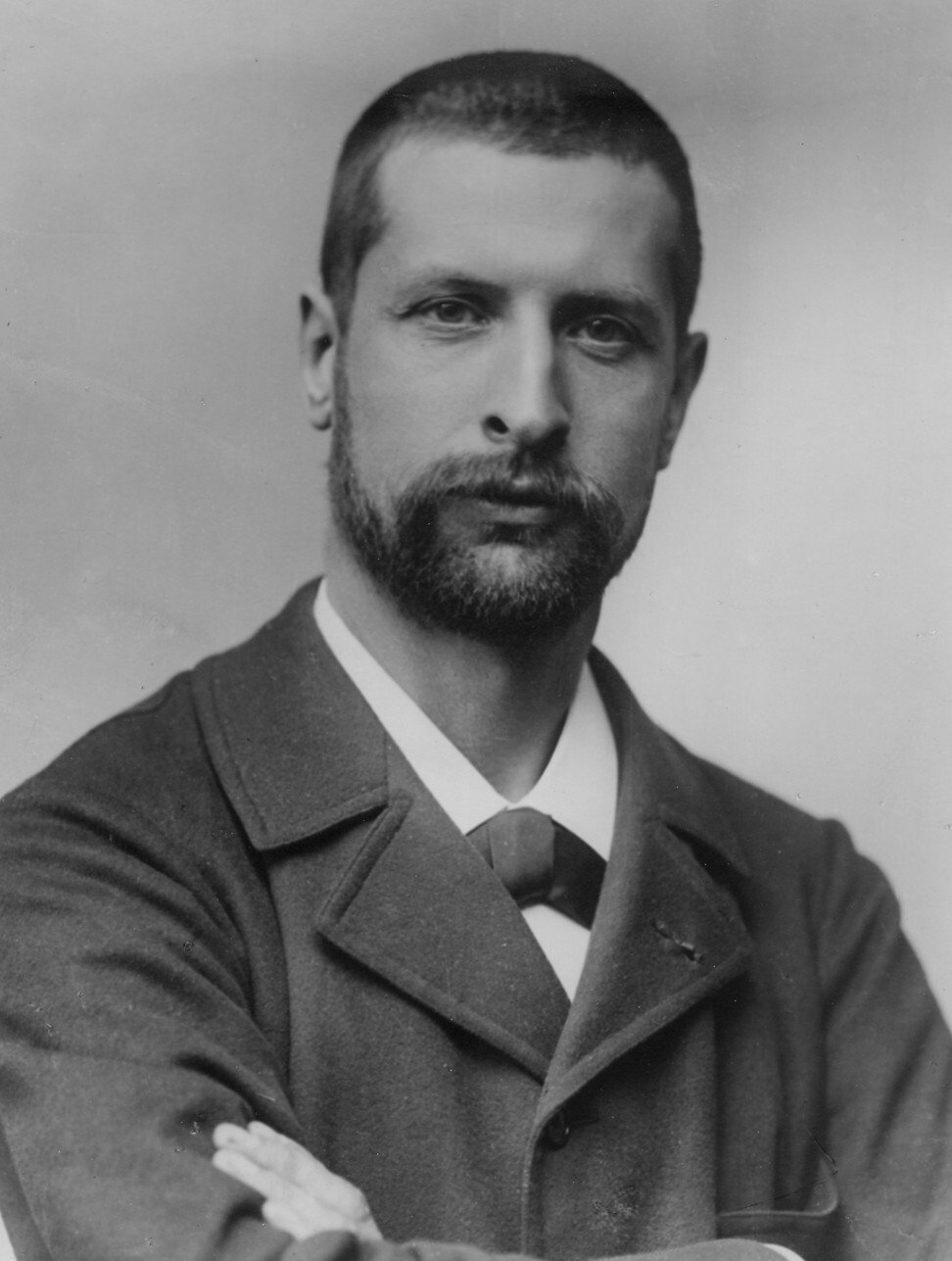

Swiss-French scientist Alexandre Yersin. Photo: Institut Pasteur

Plague would periodically resurface in Hong Kong and India until the 1940s. During what is now dubbed the “third plague pandemic”, in the 19th century, Europeans, North Americans and the Japanese were generating new mechanisms to combat illness. This scientific revolution was to liberate mankind from the virulent by-products of settled civilisation. No more leech therapy or bloodletting.

The pioneering work of bacteriologists such as Frenchman Louis Pasteur (1822-95) and German Robert Koch (1843-1910) were giving name and form to human “curses”, not as qi or miasmas, but as germs. By identifying the enemy, humans would learn how to fight it.

With people dying in such large numbers in Asia, the race was on to identify the source of the plague. It was won by Swiss-born bacteriologist Alexandre Yersin, working in a straw hut in Hong Kong. According to Dobson, he “procured cadavers of plague victims to study by bribing English sailors who had the job of disposing of bodies”. In 1894, Yersin identified Yersinia pestis, as the lethal bacteria is now known in his honour.

Japanese scientist Masanori Ogata, working in Taiwan, would suggest rat fleas carried the bacteria, a link proved in 1898 by Frenchman Paul-Louis Simond, working in India. The knowledge that killing flea-infested rats slowed the disease’s spread was critical towards overcoming it.

When plague re-emerged in China in 1910 – this time pneumonic plague, born of trade in marmot fur in Manchuria – and spread along its nascent railway network, taking more than 60,000 lives, it spurred new health care innovations. Malaysian-born, English-trained Chinese doctor Wu Lien-teh introduced quarantine, isolation, limits on travel and face masks to bring the outbreak under control by the following year, according to historian Paul French.

The straw hut “laboratory” in Hong Kong where Yersin identified the Yersinia pestis bacteria, which causes bubonic plague and was named for him. Photo: Institut Pasteur

Wu was a brilliant doctor who helped contain a potential pandemic, as well as equipping us with means to hamper future outbreaks. But racialising disease was infectious and prejudices accompanied the measures to curb disease.

As Dobson writes of plague outbreaks in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, “across the world, ports and cities struggled to contain the disease and the situation was, in many ways, reminiscent of older outbreaks, while also linked to newer issues of imperialism and race […] Blame was attached to certain groups – often, in this case, to immigrants, such as the Chinese …”

In 1882, the draconian Chinese Exclusion Act had wrote Sinophobia into law in the United States, while in Britain, in 1912, a struggling writer using the pseudonym Sax Rohmer and trading on racial stereotypes invented Fu Manchu, an opium-sickened criminal mastermind bent on world domination who would embody “Yellow Peril” for decades to come.

Meanwhile, reformers in China were trading a vision of an ill nation to further their political objectives. The term “Asia’s sick man”, which recently saw

three Wall Street Journal correspondents ejected from Beijing, might have been first applied by late-19th century political philosopher Liang Qichao, who translated Western medical texts as a call to arms against China’s antiquated culture. The lines blurred between individual health and that of the country, as Rogaski writes in Hygienic Modernity: “By creating an ideal West that ‘stresses scientific principles in all aspects of life,’ he creates a deficient China that is mired in superstition and disease.”

Liang would inspire generations of revolutionary reformers, including Sun Yat-sen, the political agitator who became the first president of the republic, in 1912; and writer Lu Xun, who studied medicine in Japan before taking up the pen to heal China’s “spiritual sickness”.

Wu Lien-teh, a Malaysia-born Chinese doctor introduced quarantine, isolation, limits on travel and face masks to bring the 1910 outbreak of plague in China under control. Photo: Handout

After the foundation of the People’s Republic of China, in 1949, the quest for scientific modernity would assume the guise of imperial China’s medical quests, collectivised under socialism. Yet progress was hampered by trouble at the top.

“Mao was almost completely ignorant of modern medicine,” wrote the Great Helmsman’s personal doctor, Li Zhisui, in his 1994 memoir The Private Life of Chairman Mao. “His thinking remained prescientific.” Li’s book tells of how Mao washed his teeth with green tea, believed smoking was a breathing exercise, abused sleeping pills and slept with a harem of young women, his “elixir for a long life”.

Mao might have been ignorant of science but he was well versed in history. Li chronicles Mao’s admiration of some of China’s great tyrants, believing everything under heaven had to be conquered, including nature, as expressed by the ancestors who had first sought to restrain the Yellow River. As Mao’s rule became more despotic, it derailed China’s efforts to modernise, medically or otherwise.

In 1958, Mao introduced the “four pests campaign”, when killing rodents, mosquitoes, flies and sparrows assumed a nationwide patriotic fervour. Yet millions of people would die, not from insect bites or rodent-borne disease but from famine as the Great Leap Forward, designed to pole-vault the country forward, failed spectacularly. Even as peasants perished in the fields, provincial cadres reported record yields, unwilling to challenge Mao’s decree. While China has come a long way since Mao’s time, the chairman casts a long shadow.

“Balance” is a concept embedded in some of China’s earliest efforts to combat disease, from the Taoist recognition of cosmic harmony to Han-era doctors who prescribed diets by the seasons. But China’s development of the past four decades has been utterly unbalanced. Cutthroat capitalism driven by utopian Marxism is now leading the country to the precipice. When the sacred threshold between the natural and human world is breached, hostile forces are unleashed – exemplified by a stressed pathogen that jumps hosts.

It’s happened before, when neolithic farmers unearthed parasitic worms from the Yellow River flood plains and when miners settled Yunnan to be greeted by the plague.

The Chinese have been shaped by their history and environment to be at once stoical and versatile. But if the world’s oldest surviving civilisation cannot adopt a more harmonious form, one akin to that propagated by Taoist sages three millennia ago, “the disease and despotism, that curse our existence” will continue to plague China.

Swiss-French scientist Alexandre Yersin. Photo: Institut Pasteur

Plague would periodically resurface in Hong Kong and India until the 1940s. During what is now dubbed the “third plague pandemic”, in the 19th century, Europeans, North Americans and the Japanese were generating new mechanisms to combat illness. This scientific revolution was to liberate mankind from the virulent by-products of settled civilisation. No more leech therapy or bloodletting.

The pioneering work of bacteriologists such as Frenchman Louis Pasteur (1822-95) and German Robert Koch (1843-1910) were giving name and form to human “curses”, not as qi or miasmas, but as germs. By identifying the enemy, humans would learn how to fight it.

With people dying in such large numbers in Asia, the race was on to identify the source of the plague. It was won by Swiss-born bacteriologist Alexandre Yersin, working in a straw hut in Hong Kong. According to Dobson, he “procured cadavers of plague victims to study by bribing English sailors who had the job of disposing of bodies”. In 1894, Yersin identified Yersinia pestis, as the lethal bacteria is now known in his honour.

Japanese scientist Masanori Ogata, working in Taiwan, would suggest rat fleas carried the bacteria, a link proved in 1898 by Frenchman Paul-Louis Simond, working in India. The knowledge that killing flea-infested rats slowed the disease’s spread was critical towards overcoming it.

When plague re-emerged in China in 1910 – this time pneumonic plague, born of trade in marmot fur in Manchuria – and spread along its nascent railway network, taking more than 60,000 lives, it spurred new health care innovations. Malaysian-born, English-trained Chinese doctor Wu Lien-teh introduced quarantine, isolation, limits on travel and face masks to bring the outbreak under control by the following year, according to historian Paul French.

The straw hut “laboratory” in Hong Kong where Yersin identified the Yersinia pestis bacteria, which causes bubonic plague and was named for him. Photo: Institut Pasteur

Wu was a brilliant doctor who helped contain a potential pandemic, as well as equipping us with means to hamper future outbreaks. But racialising disease was infectious and prejudices accompanied the measures to curb disease.

As Dobson writes of plague outbreaks in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, “across the world, ports and cities struggled to contain the disease and the situation was, in many ways, reminiscent of older outbreaks, while also linked to newer issues of imperialism and race […] Blame was attached to certain groups – often, in this case, to immigrants, such as the Chinese …”

In 1882, the draconian Chinese Exclusion Act had wrote Sinophobia into law in the United States, while in Britain, in 1912, a struggling writer using the pseudonym Sax Rohmer and trading on racial stereotypes invented Fu Manchu, an opium-sickened criminal mastermind bent on world domination who would embody “Yellow Peril” for decades to come.

Meanwhile, reformers in China were trading a vision of an ill nation to further their political objectives. The term “Asia’s sick man”, which recently saw

three Wall Street Journal correspondents ejected from Beijing, might have been first applied by late-19th century political philosopher Liang Qichao, who translated Western medical texts as a call to arms against China’s antiquated culture. The lines blurred between individual health and that of the country, as Rogaski writes in Hygienic Modernity: “By creating an ideal West that ‘stresses scientific principles in all aspects of life,’ he creates a deficient China that is mired in superstition and disease.”

Liang would inspire generations of revolutionary reformers, including Sun Yat-sen, the political agitator who became the first president of the republic, in 1912; and writer Lu Xun, who studied medicine in Japan before taking up the pen to heal China’s “spiritual sickness”.

Wu Lien-teh, a Malaysia-born Chinese doctor introduced quarantine, isolation, limits on travel and face masks to bring the 1910 outbreak of plague in China under control. Photo: Handout

After the foundation of the People’s Republic of China, in 1949, the quest for scientific modernity would assume the guise of imperial China’s medical quests, collectivised under socialism. Yet progress was hampered by trouble at the top.

“Mao was almost completely ignorant of modern medicine,” wrote the Great Helmsman’s personal doctor, Li Zhisui, in his 1994 memoir The Private Life of Chairman Mao. “His thinking remained prescientific.” Li’s book tells of how Mao washed his teeth with green tea, believed smoking was a breathing exercise, abused sleeping pills and slept with a harem of young women, his “elixir for a long life”.

Mao might have been ignorant of science but he was well versed in history. Li chronicles Mao’s admiration of some of China’s great tyrants, believing everything under heaven had to be conquered, including nature, as expressed by the ancestors who had first sought to restrain the Yellow River. As Mao’s rule became more despotic, it derailed China’s efforts to modernise, medically or otherwise.

In 1958, Mao introduced the “four pests campaign”, when killing rodents, mosquitoes, flies and sparrows assumed a nationwide patriotic fervour. Yet millions of people would die, not from insect bites or rodent-borne disease but from famine as the Great Leap Forward, designed to pole-vault the country forward, failed spectacularly. Even as peasants perished in the fields, provincial cadres reported record yields, unwilling to challenge Mao’s decree. While China has come a long way since Mao’s time, the chairman casts a long shadow.

“Balance” is a concept embedded in some of China’s earliest efforts to combat disease, from the Taoist recognition of cosmic harmony to Han-era doctors who prescribed diets by the seasons. But China’s development of the past four decades has been utterly unbalanced. Cutthroat capitalism driven by utopian Marxism is now leading the country to the precipice. When the sacred threshold between the natural and human world is breached, hostile forces are unleashed – exemplified by a stressed pathogen that jumps hosts.

It’s happened before, when neolithic farmers unearthed parasitic worms from the Yellow River flood plains and when miners settled Yunnan to be greeted by the plague.

The Chinese have been shaped by their history and environment to be at once stoical and versatile. But if the world’s oldest surviving civilisation cannot adopt a more harmonious form, one akin to that propagated by Taoist sages three millennia ago, “the disease and despotism, that curse our existence” will continue to plague China.

No comments:

Post a Comment