April 26, 2020 By Paige Steinman

Flickr/Scanpix

As the World Economic Forum notes: “Throughout history, as humans spread across the world, infectious diseases have been a constant companion.” While some of these diseases come and go, others have left the world in turmoil and tens of millions dead. Here’s a grisly in-depth look at some of the deadliest, most devastating epidemics and pandemics of all time, how they spread, and the havoc they wreaked.

1. Antonine Plague (165-180)

When the Roman army returned from their siege of ancient Mesopotamia in 165, they may have achieved a military win. But that victory came with a lot of losses in the aftermath, thanks to the germs the soldiers brought back with them. In total, five million people died during the Antonine Plague not only in the Roman Empire, but across the Mediterranean region.

Nicholas Poussin/Wikimedia Commons

While no one is exactly sure what the disease itself was, many historians guess it was a strain of measles or smallpox. When the plague began, the Roman Empire was at the height of their power. By the end, the unknown disease had killed millions of Romans, and the ranks of the once-mighty Roman military had been decimated.

2. Plague of Justinian (541-542)

To imagine the Plague of Justinian happening today would be like picturing the apocalypse happening right in front of our eyes. An astounding 25 million people (at minimum) died from this early pandemic, killing 10 percent of the entire world’s population and one-fourth of the total population living in the Eastern Mediterranean region.

Josse Lieferinxe/WIkimedia Commons

The plague’s epicenter was in Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire at the time, and was named for the Byzantine emperor himself, who managed to survive the disease. At its peak, the Plague of Justinian is believed to have killed 5,000 people in the city every single day. There was no infrastructure to support this amount of death, so corpses would sometimes be placed in the streets or in empty buildings.

3. Black Death (1347-1351)

There’s a reason the Black Death, otherwise known as the Great Bubonic Plague, remains so infamous. With jaw-dropping speed and fatality, it claimed the lives of up to 200 million people over just four years. Entire populations of towns were completely obliterated, and the dead often had to be tossed into mass graves.

Pep Roig/Alamy Stock Photo

While the Black Death hit Europe the hardest, this strain of plague is thought to have originated in Asia. The disease reportedly spread because merchants often traveled back and forth between the continents. Unbeknownst to them, as they carried with them on board goods to sell, hitching a ride were the flea-infested rats responsible for transmitting the illness.

4. New World Smallpox Outbreak (1520-1902)

While Europeans had generations to build up a natural immunity, when European explorers entered the “New World” of the Americas, the smallpox they brought with them was absolutely catastrophic to communities living there. For example, by the time the Pilgrims landed in Massachusetts, it’s estimated that 90% of local peoples had already died of smallpox germs that had traveled north from Spanish colonies. By then, nearly the entire native population of Central and South America had succumbed.

Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images

In total, over 56 million people across the Americas died as a result of smallpox. Mexico’s population crashed from around 11 million before European arrival to just one million. As it spread south, the disease was credited with weakening the Aztec and Inca Empires even before Spanish conquest. Smallpox is ancient, as evidenced from signs on 3,000-year-old Egyptian mummies, and eventually was the first pandemic to be eradicated via vaccination.

5. Italian Plague (1629-1631)

Long after the Black Death had ended, the same viral strain popped up again after troops returned home to Italy from the Thirty Years’ War. And this time, Italy would lose about 1 million of its residents. This deadly pandemic in Italy caused those who were infected to have to stay in sick houses and burn all of their possessions out of fear.

Dea Picture Library/De Agostini via Getty Images

This period also gave rise to the now-iconic plague doctors, who were paid by the city to treat everyone regardless of their wealth. These doctors famously wore a black overcoat, along with a bizarre, macabre mask featuring glass eye openings and a beak-like nose. Unfortunately, many of these doctors had little to no training, and more often than not, their patients would die.

6. Great Plague of London (1665-1666)

In the centuries following the Black Death, the bubonic plague sprang up a few more times throughout Europe, but the capital of England was the hardest hit during the Great Plague of London in 1665. During that time, 100,000 Londoners died in just seven short months. Throughout London, one of Europe’s largest cities even then, every resident was quarantined and public events were banned.

Archive Photos/Getty Images

As the wealthy fled their London homes for the countryside, the poor were left to suffer the losses. All homes where a family member was sick had to be marked with a red cross painted on their doors. As animals beyond just rats were rumored to have carried the disease, many families had to put down their livestock and pets during this tragic time.

7. Yellow Fever (1793)

In 1793, Philadelphia was the capital of the United States, and it was facing a major health crisis. In a short period of time, 5,000 people in just that city alone had died, and thousands had met a similar fate across the Eastern United States due to yellow fever.

Corbis via Getty Images

Researchers at the time knew that this outbreak had been caused primarily by mosquitoes. Because of this, they also believed that slaves who had been sent over from Africa had an immunity to this illness. Female slaves were sent to work in hospitals. In total, 100,000 to 150,000 people died of the disease during the hot summer of 1793. The epidemic only ended when the winter months killed off the mosquitoes.

8. Cholera Pandemics 1-6 (1817-1923)

In the 19th and 20th centuries, six different waves of cholera pandemics surged across the globe. They wreaked havoc throughout Asia, Europe, North America, and Africa, and cost the lives of over 1 million people worldwide. The disease’s cause, now widely-known to be caused by contaminated and unsafe food and drinking water, managed to stump researchers for a long time.

Bettmann/Getty Images

That was until the English doctor John Snow began studying the infections throughout mid-19th century England. Dr. Snow traced 500 fatal cases to one area surrounding the Broad Street water pump in London’s West End, where much of the city got its drinking water. Once a piece was removed, cases in that area cleared up, and scientists began to realize that contaminated water was a vector. However, it would be nearly a century before cholera pandemics ceased spreading.

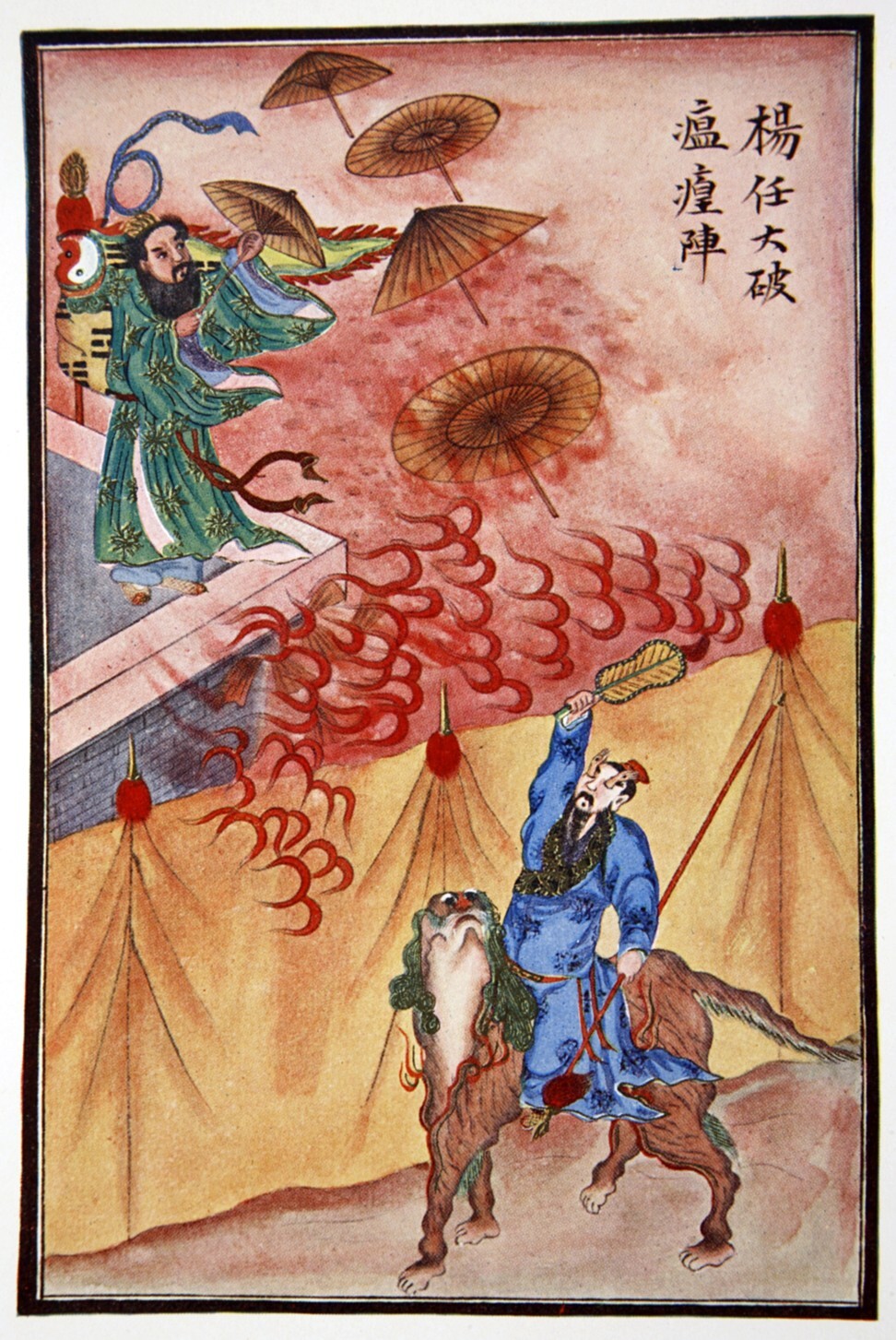

9. Third Plague (1855)

Over time, the Plague of Justinian became known as the First Plague and the Black Death was often referred to as the Second Plague. But in 1855, a new pandemic sweeping across the world killed 12 to 15 million people, landing itself a place in notoriety with its name, the Third Plague.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

This pandemic originated in Yunnan Province in southern China and ravaged both China and India, but quickly spread to every inhabited continent in the world. The disease was thought to have been caused by fleas found on rats, and just as the Black Death had traveled, it spread as these rats stowed away on cargo ships from one country to the next. That theory was later proven in 1894.

10. Russian Flu (1889-1890)

For many of the plagues and flues that came before, the world’s population was relatively safe because travel was not very easy. When these viruses spread in the past, it was largely because of cargo ships. That all changed with the arrival of the late-19th century pandemic called the Russian flu or the Asiatic flu.

Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

This virus includes Russia in its name because at that time the Russian Empire had significantly built up its railroads, causing the disease to spread rapidly within a matter of days as people traveled. By the time it ended, it had killed approximately 1 million people, and became known as the last major pandemic of the 19th century.

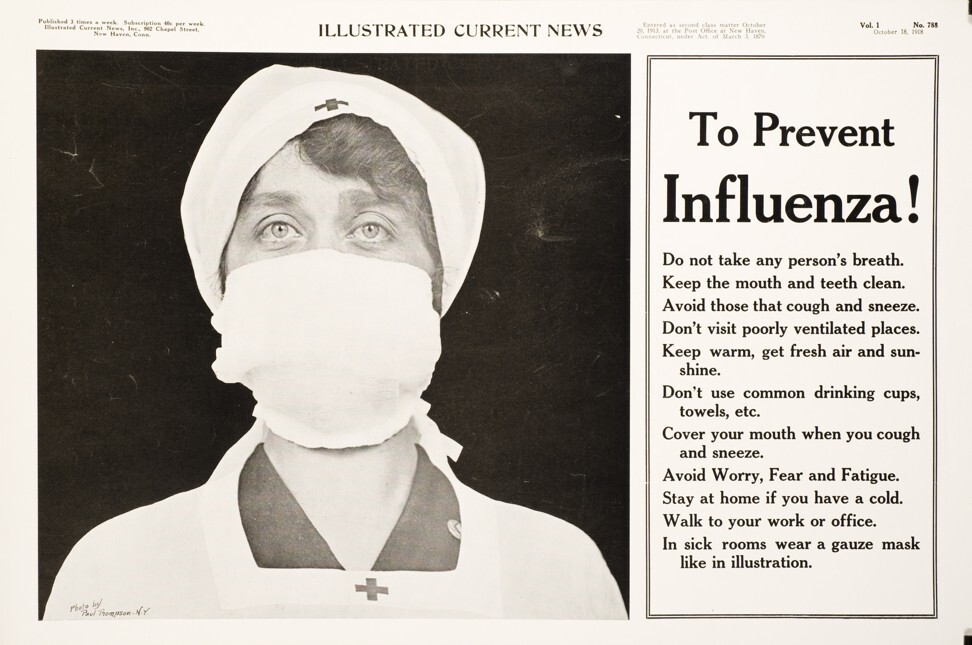

11. Spanish Flu (1918-1920)

The First World War had devastated a generation — and then, even before it had ended, along came the Spanish flu. In total, an estimated 500 million people became infected. About one-fifth of those infected, about 40 to 50 million people, died due to the illness. But while it holds the name Spanish flu, this deadly strain of influenza did not start in Spain at all.

Library of Congress/Interim Archives/Getty Images

During World War I, Spain was one of the few neutral nations, and therefore had a free press that did not censor its news. As the flu spread throughout the country, infecting even the king, the Spanish press was one of the few outlets able to freely publish its startling death tolls. This led many in the world to think that the epicenter was in Spain, though in reality, this flu had spread all over the world.

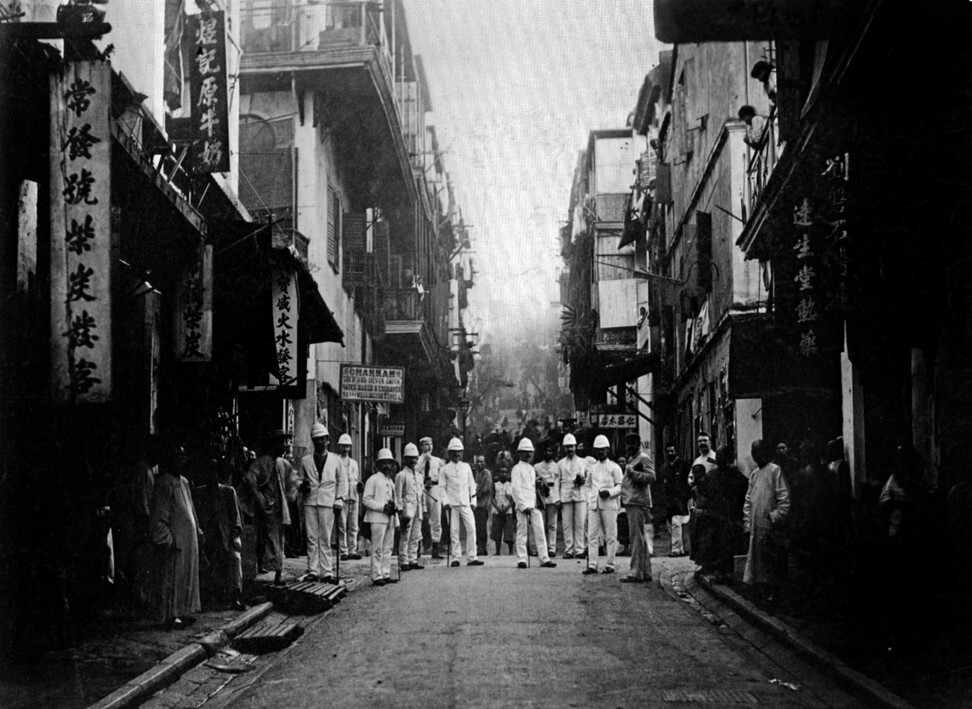

12. Asian Flu (1957-1958)

The pandemic now known as the Asian flu was an influenza strain that the world had not yet seen before. The H2N2 subtype of influenza A spread quickly. Its first outbreak was traced back to the Guizhou Province in China, and the disease had spread to Singapore by February of 1957.

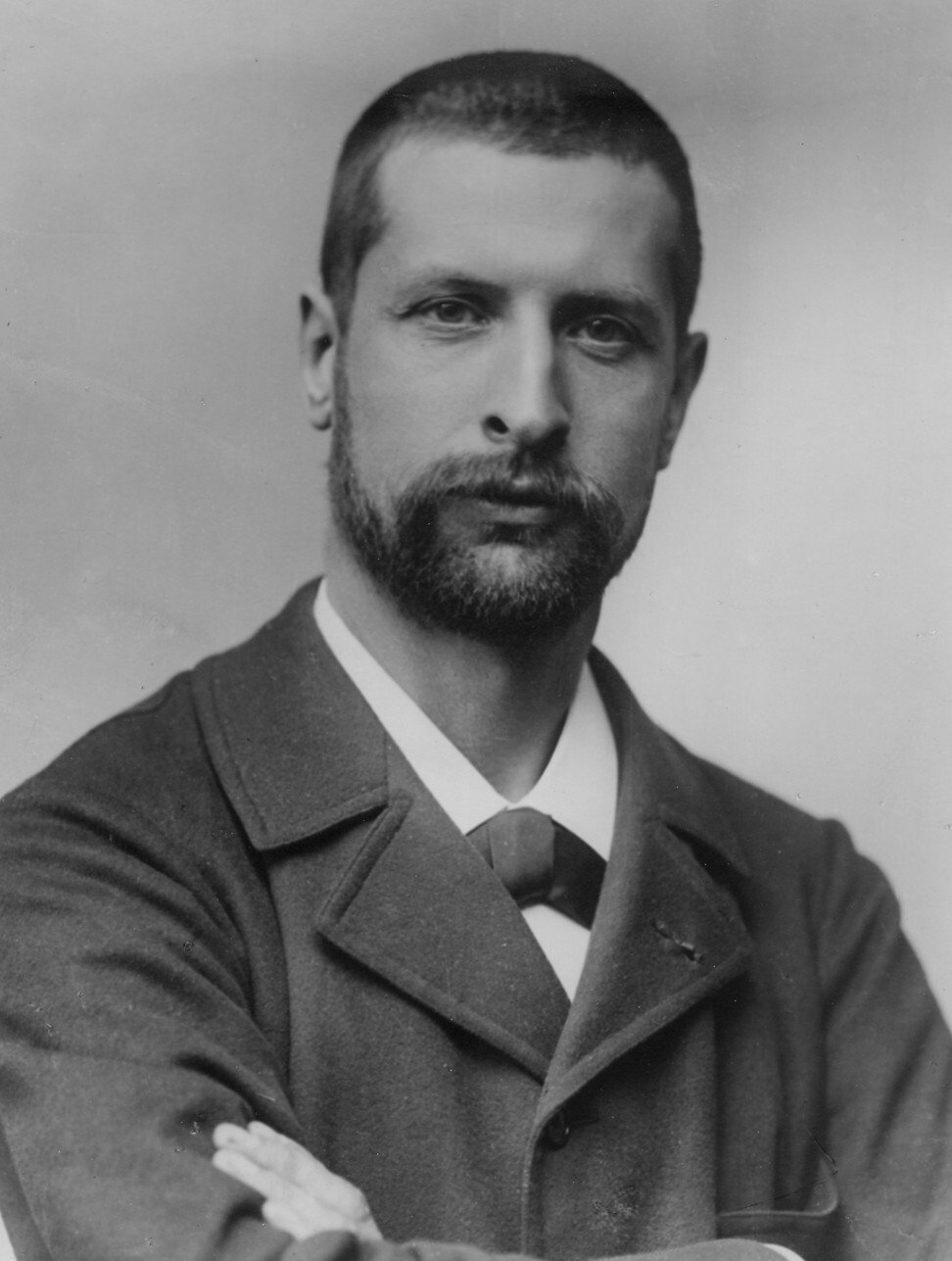

Flickr/Scanpix

By April that same year, Hong Kong was experiencing an outbreak, and by the summer of 1957, the Asian flu had reached the shores of the United States. Estimated death tolls vary, but are usually said to be between 1.1 and 2 million, with over 69,000 deaths occurring in the United States alone.

13. Hong Kong Flu (1968-1970)

The Hong Kong flu began, as the name would show, in Hong Kong, but this dangerous strain of H3N2 influenza A traveled quickly. The first case ever reported was recorded on July 13, 1968. Just 17 short days later, there were outbreaks popping up elsewhere in East Asia, in countries such as Singapore and Vietnam.

Bettmann/Getty Images

From there, the virus continued to spread throughout the Philippines, as well as infecting populations in India, Australia, Europe, and parts of the United States. Over the following few years, 1 million people died as a result, including about 500,000 people in Hong Kong, which accounted for about 15 percent of Hong Kong’s total population.

14. HIV/AIDS (1981-present)

The first official case of HIV/AIDS was identified in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1976. From there, this truly devastating pandemic has gone on to claim the lives of an estimated 35 million people worldwide. In 1980s and 1990s, the disease had reached a peak in the United States, disproportionately affecting the country’s gay and black communities.

Mark Peterson/Corbis via Getty Images

As there was no cure for decades, along with much governmental failure to adequately respond, the epidemic wiped out nearly an entire generation of gay men. While a “drug cocktail” was finally developed and brought the mortality rate down, there are still an estimated 31 to 35 million people living with HIV, most of whom reside in Sub-Saharan Africa.

15. SARS (2002-2003)

Severe acute respiratory syndrome, otherwise known as SARS, was first identified in November 2002 in China. The first “super-spreader” of SARS is believed to have been a Chinese fisherman who spread the disease to 30 nurses and doctors. And from this group, the virus quickly spread to Hong Kong, Vietnam, Canada, Taiwan, Singapore, and other parts of the world.

Joel Nito/AFP via Getty Images

At the time of the outbreak, China was criticized not only for its slow response to SARS, but also for not being very forthcoming with information related to deaths and infections. By the time the outbreak was finally contained, it had infected 8,000 people and killed nearly 800.

16. Swine Flu (2009-2010)

Swine flu was given its name because this particular strain of influenza had genetic features very similar to the type that affects pigs. Never before witnessed affecting humans, in 2000 the virus began to emerge in Mexico, causing devastation in its wake as it spread across the planet.

Alfredo Estrella/AFP via Getty Images

In just one year, an estimated 200,000 people died due to swine flu, and as many as 1.4 billion people became infected. Unlike many other flu strains, this particular flu affected young people much more frequently than those over the age of 65. After this breakout, a vaccine was developed that is now regularly administered.

17. Ebola (2014-2016)

Ebola was one of the first, if not the first, epidemic to have played out during a 24-hour news cycle. Because of this, as the story spread almost as fast as the disease itself, millions of people watched the devastating effects of ebola from their TV screens, while those living in West Africa had to watch it unfold first hand.

John Wessels/AFP via Getty Images

Ebola was not a new phenomenon. But during this particular ebola outbreak, the deadliest in history, 11,315 people died in six West African countries just 21 months after the epidemic was declared. The virus killed about 66 percent of the people it infected, turning a diagnosis into somewhat of a death sentence. In the years since, the World Health Organization has declared the region ebola-free, only for new cases to pop up almost immediately.

18. MERS (2015-Present)

Middle East respiratory syndrome, also known as MERS, was first discovered in 2012 in Saudi Arabia, giving this particular virus its name. But it took years before this strange new virus began to spread. But its travel path, although not as large as other epidemics, was deadly. For every 50 people infected with MERS, about 17 died.

Chung Sung-Jun/Getty Images

The virus, which was thought to have been passed on through infected camels, was most common in Saudi Arabia. In that country alone, 1,030 people were infected and 453 died, a roughly 44 percent fatality rate. The second most-affected country was far away in South Korea, which saw 182 cases. In total, 850 people passed away from MERS during the outbreak.

19. Zika Virus (2015-2016)

What made Zika virus so terrifying was that it did not seem to affect adults or children as much as it affected infants who were still in the womb, the most defenseless. The virus, linked to infected mosquitoes, caused thousands of babies across South and Central America to be born with underdeveloped brains, neurological problems, and small misshapen heads.

Christophe Simon/AFP via Getty Images

The outbreak became so horrifying and was spreading so rapidly that women in places like Brazil were warned to delay any pregnancies. Women across the world who were pregnant or hoped to soon be pregnant were advised not to visit affected countries.

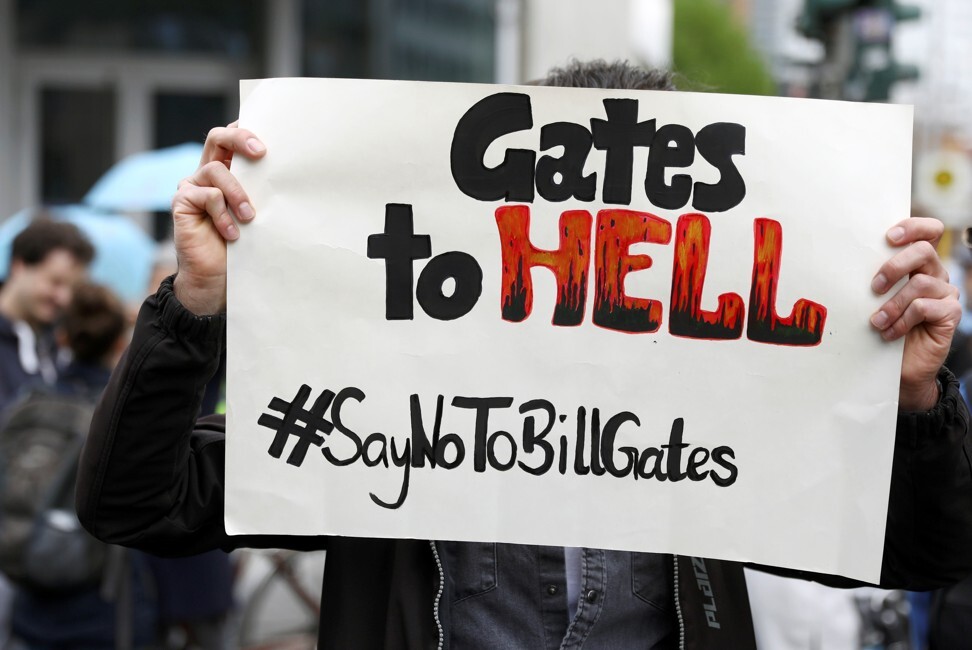

20. COVID-19 (2019-Present)

COVID-19, also referred to as Coronavirus, first began in Wuhan Province in China, but before long the entire world was feeling its crippling effects. What first started as a lockdown in Wuhan quickly turned the world into one continuous ghost town, with nearly every town and city in the world shut down for business as the virus spread.

Flickr/A Great Reckoning

Entire countries closed down for business and people were told not to leave their homes beyond absolute necessities, let alone without face masks. The number of cases and the death toll continued to climb with numbers nearly rivaling the Spanish flu. Chinese wet markets were once said to be the cause of COVID-19, though other research has disputed those claims leaving this global pandemic somewhat of a mystery.

Sources: World Economic Forum, CNN, CDC