George Floyd’s death has led the Western world to examine the privilege it has accumulated through centuries of oppression of black and other non-white people

Undoing the damage is an uncomfortable task that will take generations, but it starts by not looking away

OPINION Chandran Nair Published: 28 Jun, 2020

A woman marches during a demonstration on June 14 in Barcelona. Photo: AFP

When George Floyd was killed by a white police officer in May, it tore open the racial fault lines that have run through the United States for centuries. The impact was felt elsewhere in the Anglosphere, particularly in Britain, stirring renewed debate about the nature and scale of white privilege.

On June 18, the Church of England and the Bank of England admitted to being complicit in hundreds of years of oppression of black populations across the world. It took these institutions centuries to come out of actively practised denial, so on that front, this is a historic moment.

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, on the other hand, suggested it was unfair to “photoshop British history” when referring to the removal of statues of slave owners, as if they were somehow worth maintaining. This societal delusion and amnesia are ingrained in many white views of race issues today, aided by centuries of not having that world view challenged.

To have honest conversations about white privilege, there is a need for everyone (white or otherwise) to recognise what it is, acknowledge how widespread it is, and reflect on the damage it has done.

There is no running away from the large-scale impact resulting from European conquest of the world, which was predicated on the belief that White superiority must prevail in the world order.

Firstly, it must be understood that white privilege is a system that allows for white narratives to take hold globally and be actively spread. It is not restricted to the US and the systemic oppression of black people there. It is insidious, and it pervades many systems that govern how the modern world operates.

This globalisation of white privilege has allowed for the notion of superiority to be planted and enforced across the world, enabling other privileges to be born and old ones further enshrined.

We should be conscious of how white privilege intimidates, stifles or abuses others; and conversely, how it is actively cultivated and camouflaged for all its inherent benefits. We should examine where it makes non-whites want to imitate white people and even live like them, or how it offers a “free pass” to white people globally, often through conferred social status. And underpinning all of this, how white privilege maintains and reproduces economic power over all others.

An honest – yet respectful – examination of its ubiquity is the only way to fight contemporary white racism in all its permutations, and come to terms with the historical events that have created and spread white privilege. This goes to the heart of the global debate on race and power.

People at a rally in Missouri to protest the death of George Floyd. Photo: AP

Secondly, white people seeking to recognise their own privilege should do so in a way that does not let emotion cloud their understanding, through denying the existence of white privilege, or by seeking refuge in old arguments that racism is a global issue – and therefore racism perpetuated by white people isn’t worth singling out – to smokescreen the industrial scale of white racism over the last four centuries. Nor should we be resorting to racist insults in return.

The fact is that white privilege is unique because of its scale and global persistence. We need to be attuned to knowing where it lurks and thrives, while also understanding how often it is unrecognisable or deeply coded into long-established systems that many of us have accepted as norms.

How London’s wealth was built on the backs of slaves

24 Jun 2020

To do this, the first step is to acknowledge historical wrongdoings by coming to an agreed history of oppression and the consequent privileges that white people have accrued, which still persist and continue to be cultivated.

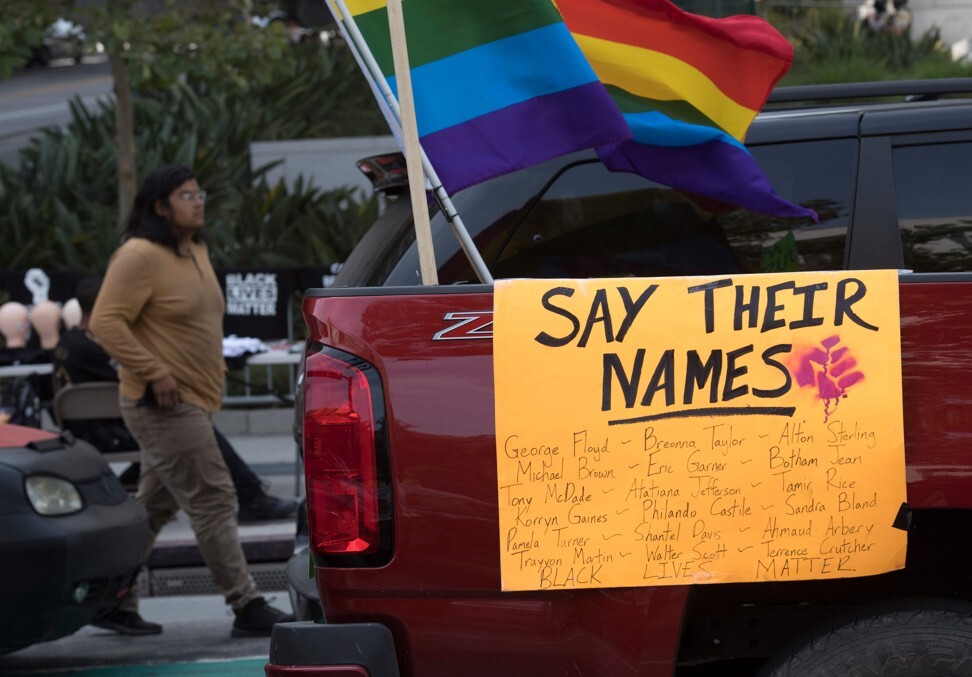

The next step is dealing with the impact of what was done across the world in the name of white supremacy. Facing these truths and undoing the damage is a monumental task that will take generations – an example is the process in South Africa. The US will need to do the same, from a national apology to deciding on reparations, and identifying and honouring all the victims of racist killings.

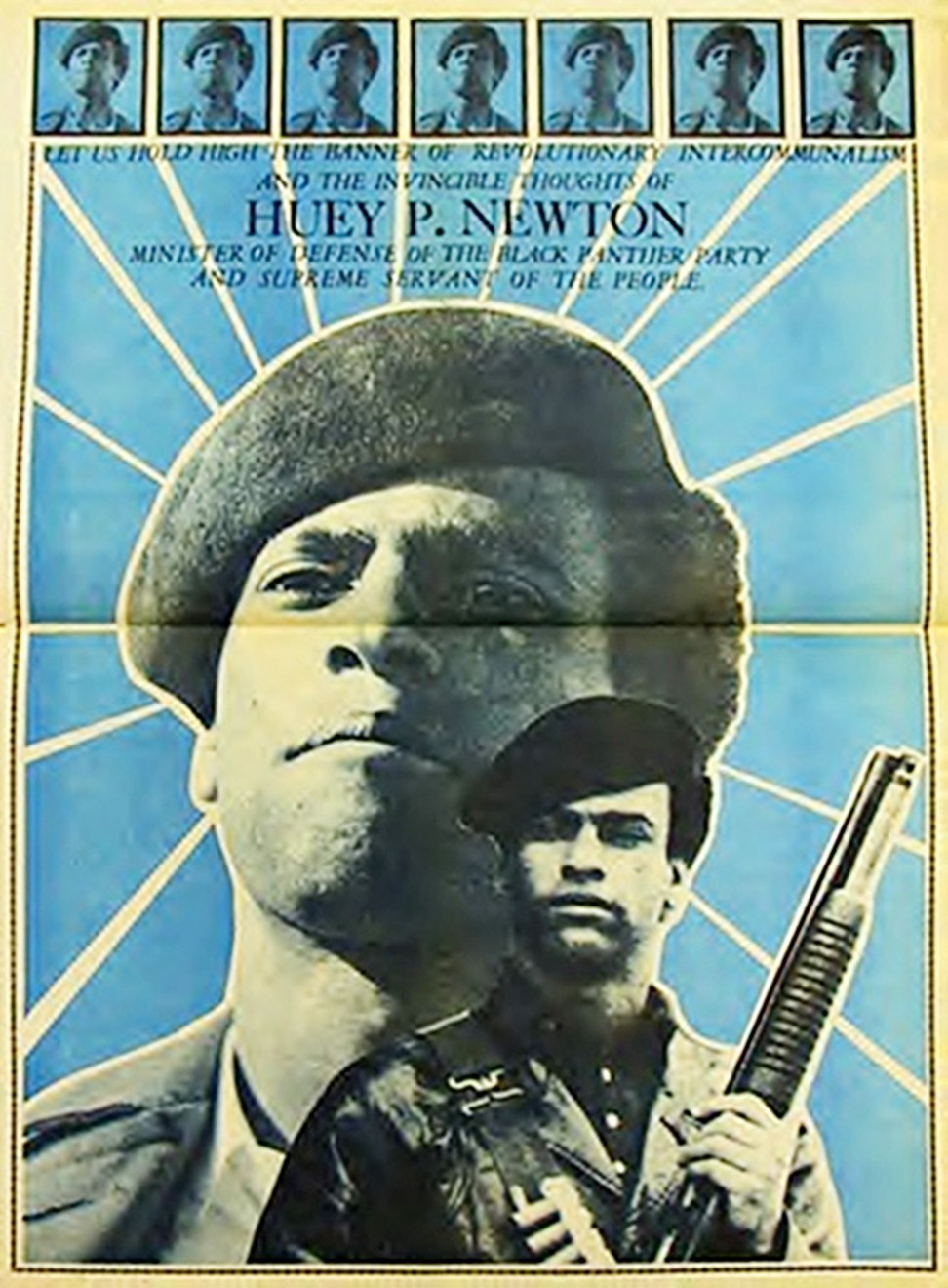

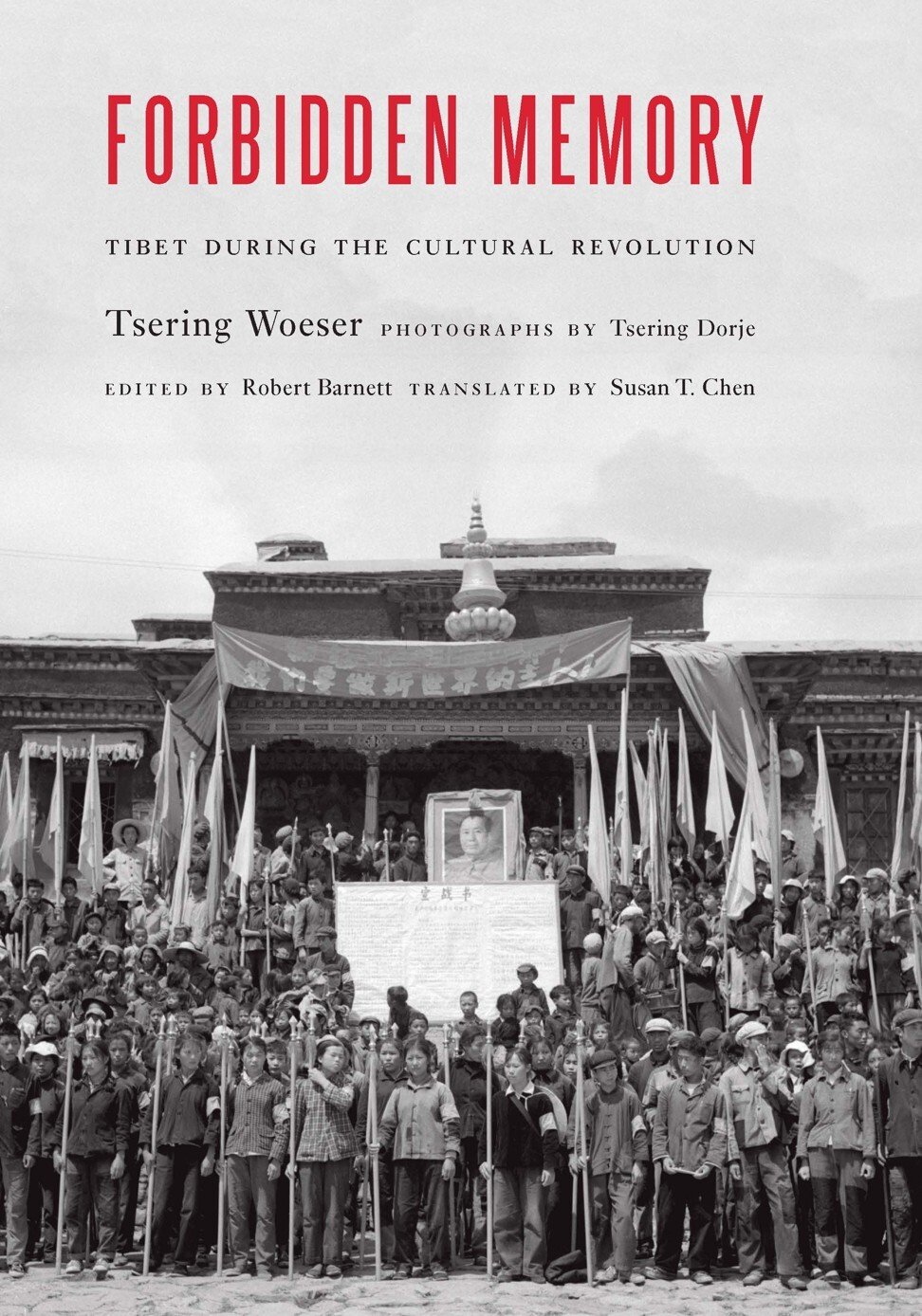

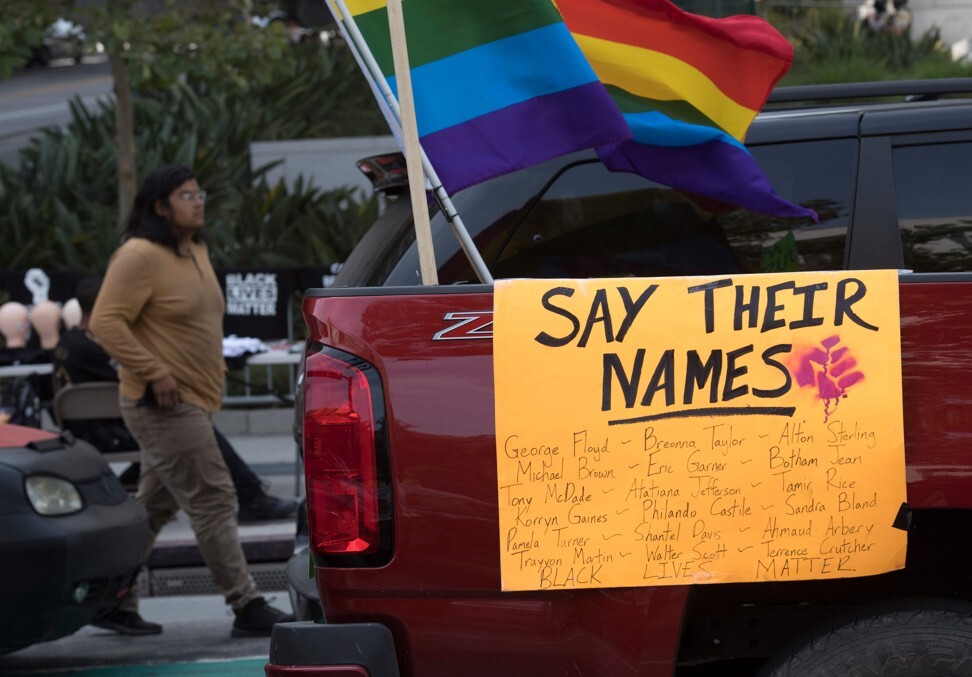

A poster seen at a protest in California on June 24, 2020. Photo: AFP

So how does white privilege manifest? How should we rethink its persistent and pervasive influence? To assist in this process, I have gathered some examples that demonstrate just how ubiquitous the perpetuation and preservation of white power is.

It is a starting point to encourage productive and honest discussions. Some may elicit discomfort, but it is high time that we do the work of dismantling white privilege and this means facing uncomfortable truths.

GEOPOLITICS

In the arena of geopolitics and multilateralism, the non-white global majority is wholly under-represented, from the United Nations Security Council to the G8.

The heads of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund are an American and a European, respectively. Two of the world’s most important multilateral institutions practise a form of apartheid. White exceptionalism ensures that the West directs the rules of the so-called rules-based world order because it fears changes to its world order.

UN condemns police brutality, systemic racism – without naming US

20 Jun 2020

At the moment, the dislike of China by the West and its media, which borders on xenophobia, is an example, and India will be next if it grows in power. Obsession with the spread of the West’s version of democracy is an instrument in this process. The Middle East has paid the highest price in recent years. The US in particular has been the driving force of this, and has been at war 225 of the 243 years since its inception, largely to spread and enforce Western democratic ideals.

The use of sanctions against opponents of the West, led by the US and, until recently, invariably supported by Europeans, is an example of trampling on international law and ignoring the deaths of hundreds of thousands, none of whom are white.

Western brands such as Starbucks are idealised as business heroes. Photo: SCMP

BUSINESS

In the business world, the promotion of ideas about globalisation, free markets, role of finance, are all done in accordance with the Western rule book.

A key vehicle for the spread of this ideology has been the leading Western business schools, and their march across regions like Asia has been relentless. They invariably idealise the superheroes of the Western business world, from Amazon to Apple and Starbucks.

The gatekeepers of the rules of governance of international business, despite systematically failing in their roles, are a cartel of four: Deloitte, PwC, Ernst & Young and KPMG, all of which are Western-owned.

In the US, China-bashing is rooted in myths of Western superiority

24 Jun 2020

The same dominance is to be seen in the business consulting world through a handful of mainly US firms – McKinsey, BCG, Bain – as they churn out the same old ideas.

For IPOs and M&A, no global deal can be led by any legal firm except the largest ones from the US or Britain.

Leading investment banks worldwide are all Western, and some in the US have egregious histories of funding slave plantation expansion and even providing insurance for slave owners.

When it comes to ratings agencies, S&P Global Ratings, Moody’s, and Fitch Group are all Western, with no accord for a non-Western ratings organisation to join their ranks.

The West closing its doors to Huawei is an example of keeping the tech world in the control of Western powers.

The global ranking of universities and business schools is set by Western establishments. File photo: AFP

EDUCATION AND MINDS

Education is an area where examples abound. The prestige accorded to Western Ivy League universities, including the lavish donations to these institutions, even by Asians is a case in point.

Oxford and Cambridge, even in this day and age, have continued global pre-eminence, especially in former colonies. The global ranking of universities and business schools is dominated by Western establishments, and is perpetuated by Western publications with their eagerly awaited annual ranking.

Anglicising Asian names: another form of racism? Just ask Phuc Bui

24 Jun 2020

Models of Western education across all development stages are practised as the “pinnacle” of education across Asia and Africa.

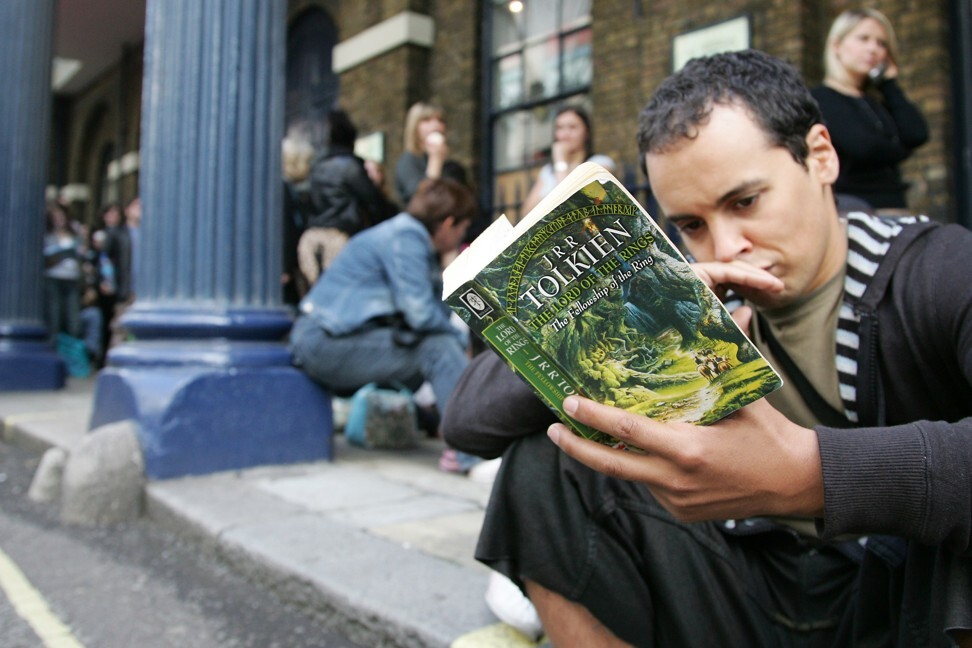

Selective teachings of history are a particular irony. Fiction, philosophy and other lessons from Western, mostly male, authors have a special place in the literary canon, and are exported and venerated the world over – Dante, Homer, Kant, Shakespeare, Tolkien, and so on – while other literary greats or philosophers from non-white countries are majorly unknown.

The week to June 13 was the first time in British history that a black British author topped the UK book charts.

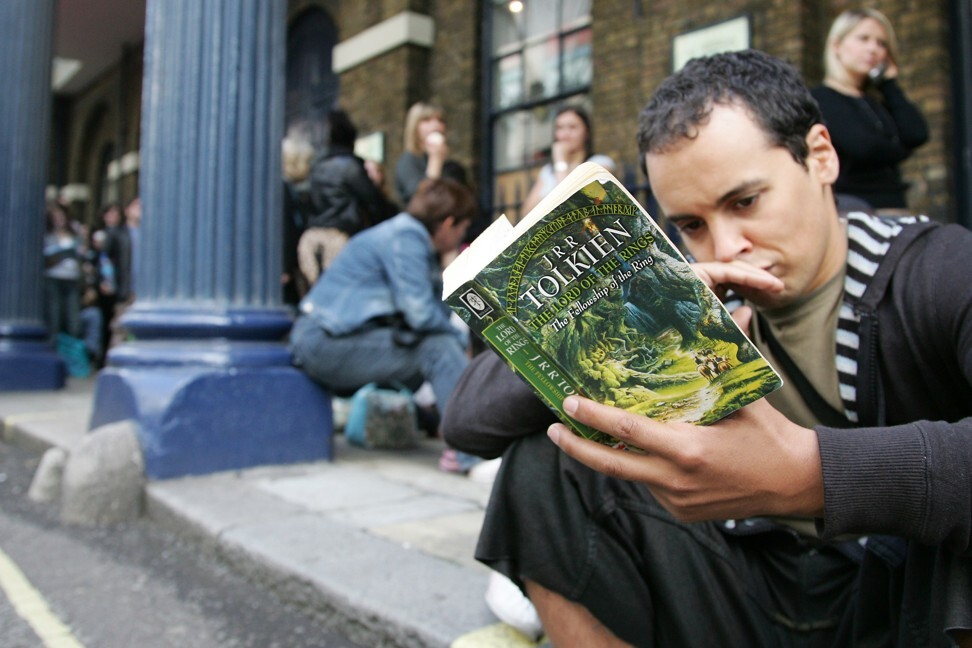

Books by Western authors such as JRR Tolkein have a special place in the literary canon. File photo: AP

MEDIA

The Western media plays an important role in this scheme of things. From outlets such as the BBC and CNN to The Guardian, Financial Times and The New York Times, Western media shapes the information that global middle classes and elites consume.

English is the lingua franca of the modern world, meaning English-sourced narratives are predominant. This is changing as other nations join the international media fold, resulting in one of the biggest ideological reckonings of our times as media discourse between the West and the Rest ekes it out on a multitude of platforms.

In addition, which books get published and put on global bestseller lists is largely decided by the Western publishing world. Few books on politics, economics, development or environment written in non-English languages are ever translated for a global audience.

The songs defining Black Lives Matter protests in the US

17 Jun 2020

Western publishing agents favour Western authors and certain narratives. Only

select Asian or African writers who pander to the taste of Western audiences and their politics make it in – including stories about the monsoons, romantic views on Africa, white saviours, or awful indictments of the countries they hail from.

In the global media, commentary is dominated by Western writers and aligned to associated ideologies. Current fads include China-bashing, the dangers of a new world order, even climate – but seen through the narrow lens of the Western experience.

Leading global media outlets are blind to white privilege narratives and thus perpetuate it by the decisions they make daily in the narratives they choose to broadcast.

Peking opera is centuries older than Western opera. File photo: Reuters

On June 18, the Church of England and the Bank of England admitted to being complicit in hundreds of years of oppression of black populations across the world. It took these institutions centuries to come out of actively practised denial, so on that front, this is a historic moment.

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, on the other hand, suggested it was unfair to “photoshop British history” when referring to the removal of statues of slave owners, as if they were somehow worth maintaining. This societal delusion and amnesia are ingrained in many white views of race issues today, aided by centuries of not having that world view challenged.

To have honest conversations about white privilege, there is a need for everyone (white or otherwise) to recognise what it is, acknowledge how widespread it is, and reflect on the damage it has done.

There is no running away from the large-scale impact resulting from European conquest of the world, which was predicated on the belief that White superiority must prevail in the world order.

Firstly, it must be understood that white privilege is a system that allows for white narratives to take hold globally and be actively spread. It is not restricted to the US and the systemic oppression of black people there. It is insidious, and it pervades many systems that govern how the modern world operates.

This globalisation of white privilege has allowed for the notion of superiority to be planted and enforced across the world, enabling other privileges to be born and old ones further enshrined.

We should be conscious of how white privilege intimidates, stifles or abuses others; and conversely, how it is actively cultivated and camouflaged for all its inherent benefits. We should examine where it makes non-whites want to imitate white people and even live like them, or how it offers a “free pass” to white people globally, often through conferred social status. And underpinning all of this, how white privilege maintains and reproduces economic power over all others.

An honest – yet respectful – examination of its ubiquity is the only way to fight contemporary white racism in all its permutations, and come to terms with the historical events that have created and spread white privilege. This goes to the heart of the global debate on race and power.

People at a rally in Missouri to protest the death of George Floyd. Photo: AP

Secondly, white people seeking to recognise their own privilege should do so in a way that does not let emotion cloud their understanding, through denying the existence of white privilege, or by seeking refuge in old arguments that racism is a global issue – and therefore racism perpetuated by white people isn’t worth singling out – to smokescreen the industrial scale of white racism over the last four centuries. Nor should we be resorting to racist insults in return.

The fact is that white privilege is unique because of its scale and global persistence. We need to be attuned to knowing where it lurks and thrives, while also understanding how often it is unrecognisable or deeply coded into long-established systems that many of us have accepted as norms.

How London’s wealth was built on the backs of slaves

24 Jun 2020

To do this, the first step is to acknowledge historical wrongdoings by coming to an agreed history of oppression and the consequent privileges that white people have accrued, which still persist and continue to be cultivated.

The next step is dealing with the impact of what was done across the world in the name of white supremacy. Facing these truths and undoing the damage is a monumental task that will take generations – an example is the process in South Africa. The US will need to do the same, from a national apology to deciding on reparations, and identifying and honouring all the victims of racist killings.

A poster seen at a protest in California on June 24, 2020. Photo: AFP

So how does white privilege manifest? How should we rethink its persistent and pervasive influence? To assist in this process, I have gathered some examples that demonstrate just how ubiquitous the perpetuation and preservation of white power is.

It is a starting point to encourage productive and honest discussions. Some may elicit discomfort, but it is high time that we do the work of dismantling white privilege and this means facing uncomfortable truths.

GEOPOLITICS

In the arena of geopolitics and multilateralism, the non-white global majority is wholly under-represented, from the United Nations Security Council to the G8.

The heads of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund are an American and a European, respectively. Two of the world’s most important multilateral institutions practise a form of apartheid. White exceptionalism ensures that the West directs the rules of the so-called rules-based world order because it fears changes to its world order.

UN condemns police brutality, systemic racism – without naming US

20 Jun 2020

At the moment, the dislike of China by the West and its media, which borders on xenophobia, is an example, and India will be next if it grows in power. Obsession with the spread of the West’s version of democracy is an instrument in this process. The Middle East has paid the highest price in recent years. The US in particular has been the driving force of this, and has been at war 225 of the 243 years since its inception, largely to spread and enforce Western democratic ideals.

The use of sanctions against opponents of the West, led by the US and, until recently, invariably supported by Europeans, is an example of trampling on international law and ignoring the deaths of hundreds of thousands, none of whom are white.

Western brands such as Starbucks are idealised as business heroes. Photo: SCMP

BUSINESS

In the business world, the promotion of ideas about globalisation, free markets, role of finance, are all done in accordance with the Western rule book.

A key vehicle for the spread of this ideology has been the leading Western business schools, and their march across regions like Asia has been relentless. They invariably idealise the superheroes of the Western business world, from Amazon to Apple and Starbucks.

The gatekeepers of the rules of governance of international business, despite systematically failing in their roles, are a cartel of four: Deloitte, PwC, Ernst & Young and KPMG, all of which are Western-owned.

In the US, China-bashing is rooted in myths of Western superiority

24 Jun 2020

The same dominance is to be seen in the business consulting world through a handful of mainly US firms – McKinsey, BCG, Bain – as they churn out the same old ideas.

For IPOs and M&A, no global deal can be led by any legal firm except the largest ones from the US or Britain.

Leading investment banks worldwide are all Western, and some in the US have egregious histories of funding slave plantation expansion and even providing insurance for slave owners.

When it comes to ratings agencies, S&P Global Ratings, Moody’s, and Fitch Group are all Western, with no accord for a non-Western ratings organisation to join their ranks.

The West closing its doors to Huawei is an example of keeping the tech world in the control of Western powers.

The global ranking of universities and business schools is set by Western establishments. File photo: AFP

EDUCATION AND MINDS

Education is an area where examples abound. The prestige accorded to Western Ivy League universities, including the lavish donations to these institutions, even by Asians is a case in point.

Oxford and Cambridge, even in this day and age, have continued global pre-eminence, especially in former colonies. The global ranking of universities and business schools is dominated by Western establishments, and is perpetuated by Western publications with their eagerly awaited annual ranking.

Anglicising Asian names: another form of racism? Just ask Phuc Bui

24 Jun 2020

Models of Western education across all development stages are practised as the “pinnacle” of education across Asia and Africa.

Selective teachings of history are a particular irony. Fiction, philosophy and other lessons from Western, mostly male, authors have a special place in the literary canon, and are exported and venerated the world over – Dante, Homer, Kant, Shakespeare, Tolkien, and so on – while other literary greats or philosophers from non-white countries are majorly unknown.

The week to June 13 was the first time in British history that a black British author topped the UK book charts.

Books by Western authors such as JRR Tolkein have a special place in the literary canon. File photo: AP

MEDIA

The Western media plays an important role in this scheme of things. From outlets such as the BBC and CNN to The Guardian, Financial Times and The New York Times, Western media shapes the information that global middle classes and elites consume.

English is the lingua franca of the modern world, meaning English-sourced narratives are predominant. This is changing as other nations join the international media fold, resulting in one of the biggest ideological reckonings of our times as media discourse between the West and the Rest ekes it out on a multitude of platforms.

In addition, which books get published and put on global bestseller lists is largely decided by the Western publishing world. Few books on politics, economics, development or environment written in non-English languages are ever translated for a global audience.

The songs defining Black Lives Matter protests in the US

17 Jun 2020

Western publishing agents favour Western authors and certain narratives. Only

select Asian or African writers who pander to the taste of Western audiences and their politics make it in – including stories about the monsoons, romantic views on Africa, white saviours, or awful indictments of the countries they hail from.

In the global media, commentary is dominated by Western writers and aligned to associated ideologies. Current fads include China-bashing, the dangers of a new world order, even climate – but seen through the narrow lens of the Western experience.

Leading global media outlets are blind to white privilege narratives and thus perpetuate it by the decisions they make daily in the narratives they choose to broadcast.

Peking opera is centuries older than Western opera. File photo: Reuters

CULTURE AND ENTERTAINMENT

Culture and entertainment has been one of the most powerful tools in promoting White superiority.

Hollywood leads the charge through movies, ranging from the promotion of Tarzan, John Wayne and Marilyn Monroe to the movies that vilified black people, Geronimo, the Yellow Peril, and portrayed freedom fighters from white colonisers as terrorists.

Why the BTS Army and other K-pop fans are aiming their activism at Trump

23 Jun 2020

Western pop music was another powerful tool with its global spread, making the Beatles and the Rolling Stones global icons – not Chuck Berry or Bo Diddley – while music from non-Western countries is callously labelled “world music”.

Western classical music is revered as a cultural pinnacle, while non-Western classical music is sidelined or not broadcast. Ballet is the ultimate historical dance form, not Kathakali from India or Shen Yun from China. The global prominence of Western opera, and not Peking opera – which is centuries older – paints the same picture.

US rock ‘n’ roll legend Chuck Berry. File photo: AFP

SPORT

Culture and entertainment has been one of the most powerful tools in promoting White superiority.

Hollywood leads the charge through movies, ranging from the promotion of Tarzan, John Wayne and Marilyn Monroe to the movies that vilified black people, Geronimo, the Yellow Peril, and portrayed freedom fighters from white colonisers as terrorists.

Why the BTS Army and other K-pop fans are aiming their activism at Trump

23 Jun 2020

Western pop music was another powerful tool with its global spread, making the Beatles and the Rolling Stones global icons – not Chuck Berry or Bo Diddley – while music from non-Western countries is callously labelled “world music”.

Western classical music is revered as a cultural pinnacle, while non-Western classical music is sidelined or not broadcast. Ballet is the ultimate historical dance form, not Kathakali from India or Shen Yun from China. The global prominence of Western opera, and not Peking opera – which is centuries older – paints the same picture.

US rock ‘n’ roll legend Chuck Berry. File photo: AFP

SPORT

Sport is not spared and is rife with racism. Ownership, management and coaching of the NBA, NFL, leading football clubs, and other major sports around the world are dominated by white people.

In certain sports such as basketball, black players act as modern-day gladiators and entertainers in arenas that cater to mainly white businesses and audiences, with sporting successes attributed to race and genetics, not individual hard work and intelligence.

Racism in European football has been co-opted into a liberal cause restricted to the sporting world, without confronting the deeper structural issues within society that enable this manifestation of racism in the first place.

I remember

https://t.co/KIRWpMHd62

— Vanessa Nakate (@vanessa_vash)

June 4, 2020

SAVING THE PLANET

When it comes to saving the planet, so-called global solutions are seen through the lens of the Western political economy and economists, the belief that no sacrifice – including a change in lifestyle – is needed to reconcile free market failings with environmental destruction and the rights of the global majority.

The belief that solutions to climate change and other global environmental challenges can only come from the research centres, leaders, activists and spokespersons from the West is widespread.

Teenage activist Greta Thunberg is now an icon – it is hard to think that a young African or Asian person would be cultivated into a global figure in a similar manner.

Non-Western experts and voices are ignored or silenced, despite climate change disproportionately impacting socioeconomically less-advantaged populations, most of whom live in non-white countries.

US fashion model Halima Aden, a refugee from Kenya, broke boundaries in 2017 as the first hijab-wearing model to grace magazine covers and walk in high-profile runway shows. Photo: Reuters

FASHION

The rarefied world of high fashion is an important influencer. Leading fashion houses are all Western and promote white fashion styles.

A white sense of female beauty has permeated the non-Western world – slim, sexualised and fair (including skin-whitening products and complexes).

How skin whiteners are promoting unhealthy beauty norms in Asia

3 Jun 2019

The hijab is perceived as oppressive, while a bikini is viewed as freedom. Then there is the erosion of traditional attire – replacing the Indian sari or the Burmese longyi with a Chanel outfit or Hugo Boss fabrics, both in the home and the workplace.

Cultures of fashion are belittled or appropriated. For example, indigenous clothing is looked down upon until it is co-opted by fashion houses. Gucci created a jumper that mimicked blackface last year. Commes Des Garcons made blonde cornrow wigs for white models this year.

The statue of former British prime minister Winston Churchill is seen defaced at a rally in London outside the US Embassy on June 7. Photo: AFP

HISTORY

US fashion model Halima Aden, a refugee from Kenya, broke boundaries in 2017 as the first hijab-wearing model to grace magazine covers and walk in high-profile runway shows. Photo: Reuters

FASHION

The rarefied world of high fashion is an important influencer. Leading fashion houses are all Western and promote white fashion styles.

A white sense of female beauty has permeated the non-Western world – slim, sexualised and fair (including skin-whitening products and complexes).

How skin whiteners are promoting unhealthy beauty norms in Asia

3 Jun 2019

The hijab is perceived as oppressive, while a bikini is viewed as freedom. Then there is the erosion of traditional attire – replacing the Indian sari or the Burmese longyi with a Chanel outfit or Hugo Boss fabrics, both in the home and the workplace.

Cultures of fashion are belittled or appropriated. For example, indigenous clothing is looked down upon until it is co-opted by fashion houses. Gucci created a jumper that mimicked blackface last year. Commes Des Garcons made blonde cornrow wigs for white models this year.

The statue of former British prime minister Winston Churchill is seen defaced at a rally in London outside the US Embassy on June 7. Photo: AFP

HISTORY

And finally there is the writing and teaching of history. In Western retelling of wars, there are often no non-Western heroes. In World War II, millions from Africa and Asia were denied their basic freedoms and died fighting for the West in a war that was waged to determine which Western country would continue to exploit them.

There is also the brushing aside of the crimes of the West – Churchill and his involvement in the genocide of 4 million Bengalis in 1943 is an example.

Colonial figures reassessed worldwide after George Floyd’s death

12 Jun 2020

Equally, no US history book regales you with how many native Americans were killed by white settlers, but US historians have precise numbers for atrocities committed by other nations.

There has been no apology for dropping a nuclear bomb on the people of Japan or for the three million killed in the Vietnam war and the carpet bombing of Laos.

Women in Vietnam still have Agent Orange in their breast milk and birth deformities run into the tens of thousands. Or even historical recognition of the crimes against humanity committed in the European conquest of the lands of native Americans, the First Nation Peoples of CANADA, Australia, or the Māori of New Zealand.

Protesters participate in a Black Lives Matter rally in Brisbane on June 6. Photo: EPA-EFE

Citing these examples is not to say that other races, nations or cultures have not engaged in racism, slavery, crimes against humanity or oppression of other civilisations.

Most have and some still do – just as the US does with its prison system today, there is the Indian caste system, racism against black people across Asia, and the infringement of the rights of girls and women in numerous parts of the non-Western world.

But there is no running away from the large-scale impact resulting from European conquest of the world, which was predicated on the belief that white superiority must prevail in the world order.

It has ultimately shaped a world that – even today – is marked by global white privilege.

Black Lives Matter protests held across Asia

These interventions have also resulted in intra-national fragility and conflicts that persist today – for example, the conflicts in Myanmar, Kashmir, DR Congo and Palestine, to name a few.

We live in a moment when the #BlackLivesMatter movement provides a rare opportunity to expose and rectify practices which have, for far too long, been conveniently ignored in the interests of preserving and protecting white privilege.

Thus, if as a reader you find yourself thinking, “But Western intervention has helped create the globalised world we see today, with opportunities for prosperity in all countries”, or conclude that the points in the list above are simply manifestations of things that white people are “just better at”, then you are falling into the same trap that catches white supremacists.

This is where the hard work must be done: to dismantle the deeply ingrained mindsets that many of us possess. It’s not comfortable, it’s not easy, but now is the time to start.

It starts by not looking away.

Chandran Nair is the founder and CEO of the Global Institute for Tomorrow. He is the author of The Sustainable State . He lived and worked in southern Africa during the years of the liberation struggle.