From cultural prop to circus freak: the first Chinese woman in US

Afong Moy was brought to the US in 1834 to help sell Chinese goods to an eager American middle class, writes historian Nancy E. Davis

She met president Andrew Jackson and served as a cultural bridge, but ended up in a circus sideshow being mocked for her differences

Martin Witte Published: 3 Sep, 2019

An engraving of Afong Moy. Referred to as “the first Chinese woman to arrive in America”, Moy served as a cultural bridge between China and the United States, including in private and among elites, but was eventually relegated to little more than a sensationalised caricature resulting from racial and ethnic tensions.

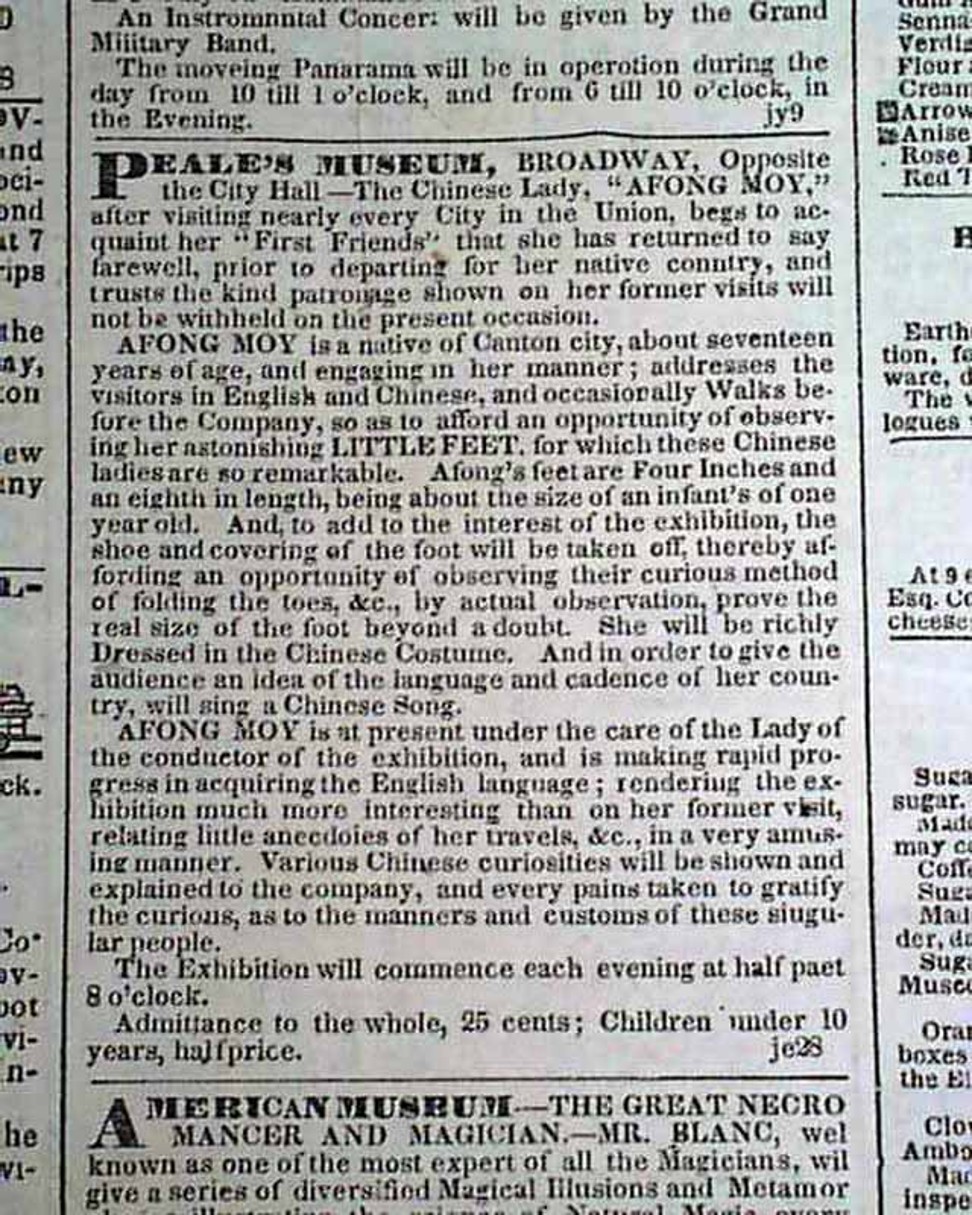

The Chinese Lady: Afong Moy in Early America, by Nancy E. Davis. Published by Oxford University Press. 4 stars.

It requires an inventive streak to write extensively about a person whose known biography only fills a few pages. This is the long shot taken in The Chinese Lady: Afong Moy in Early America, by historian Nancy E. Davis, who refers to her as “the first Chinese woman to arrive in America”.

Davis’s ambition pays off. She augments scant available material about Moy, who was brought to the United States as a “cultural prop” to help sell Chinese goods, by painting in the negative space around her. While keeping Moy in sight, Davis branches off to detail, among other topics, the foundation of US-China trade and cultural ties, the beginnings of China’s manufacturing industry, and the transformation of 19th-century American society.

Moy arrived in New York in October 1834 at about 16 years of age. She has a documented history in the country spanning 17 years, the middle half of which were spent in relative obscurity in a poorhouse in New Jersey.

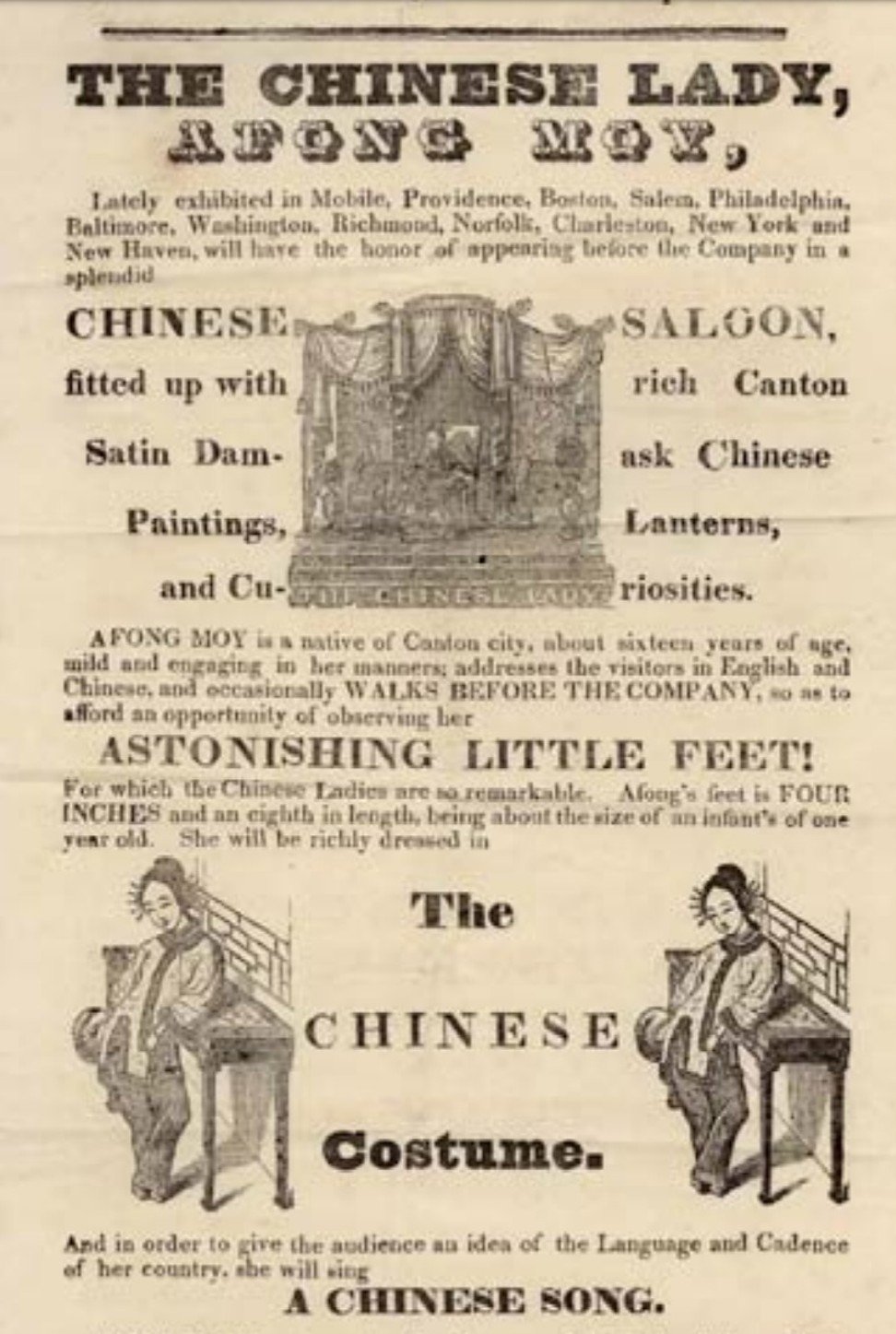

An advertisement for an “exhibition” of Afong Moy.

Davis divides Moy’s public life into two acts. First, she was an exotic “presenter” of Chinese-made goods. Later, after an absence from a leering public – fallout from the economic panic of 1837 made her an expendable luxury – she became a sideshow attraction from the late 1840s, mainly under the devices of American showman PT Barnum.

There are no known photographs of Moy, no reliable idea about how she felt about her experiences in America, and no record of her at all after 1850.

The merchants who brought her over from the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou (it seems that “money likely changed hands”) played up her “exoticism” – her bound feet, clothing and accessories – to promote the “authenticity” of Chinese imports.

She was taken on a 1,600-kilometre (1,000-mile) tour from New York to New Orleans, with a stop in Cuba, posing on stages alongside Chinese wares for sale. Moy was viewed by thousands of people, most of whom paid a small fee to lay their eyes on a Chinese woman for the first time.

Davis frequently references a lithograph printed to advertise Moy’s earliest “demonstrations”. The image most often associated with Moy (it is unknown whether it is an actual likeness) depicts her in Chinese dress and surrounded by vases, chairs, textiles and other products. The items displayed – like many Chinese goods manufactured today for foreign markets – were mass-produced, often knocked-off from European designs, and marked up in price for an American middle class eager to reap the rewards of expanding trade with China.

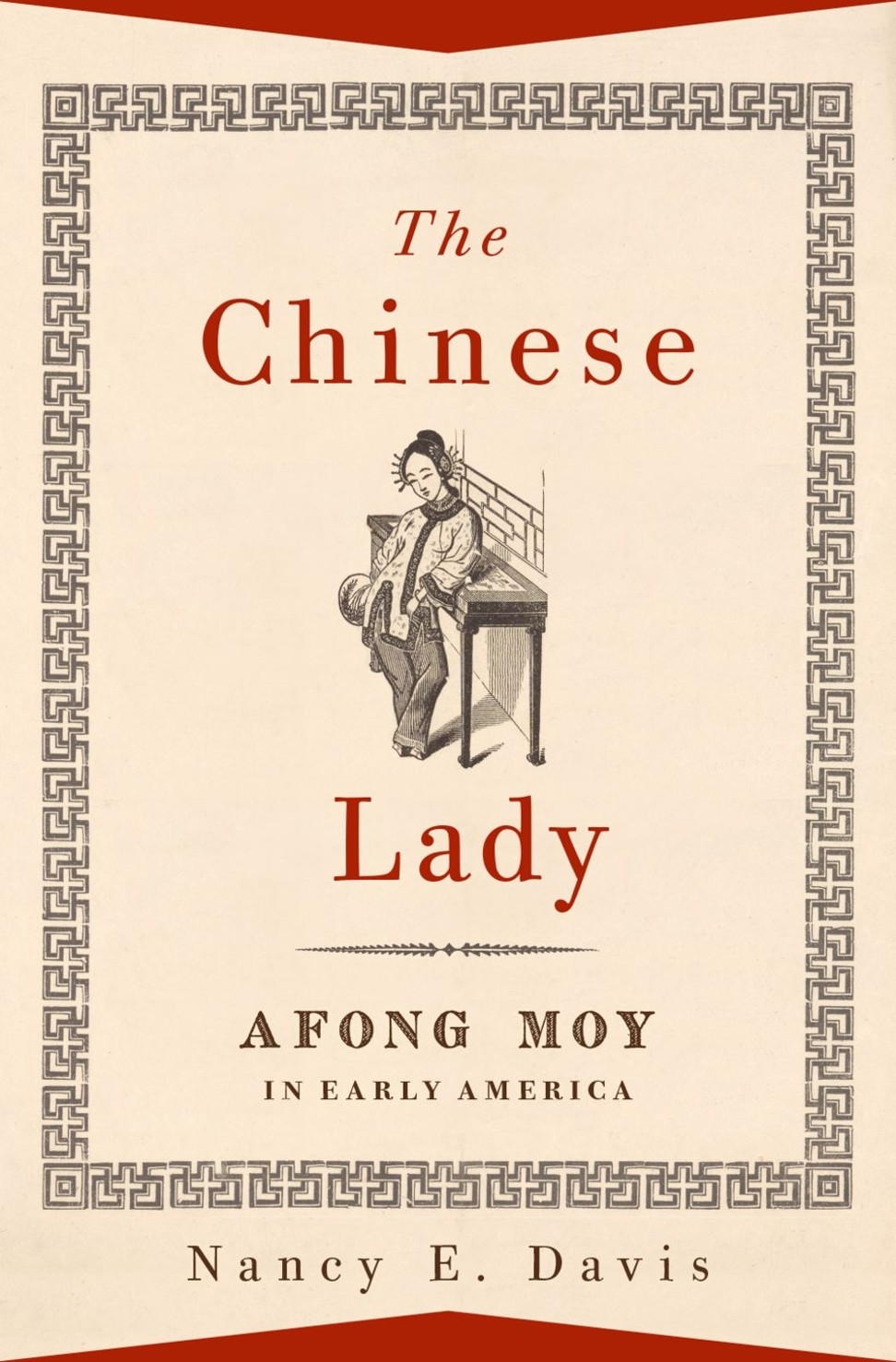

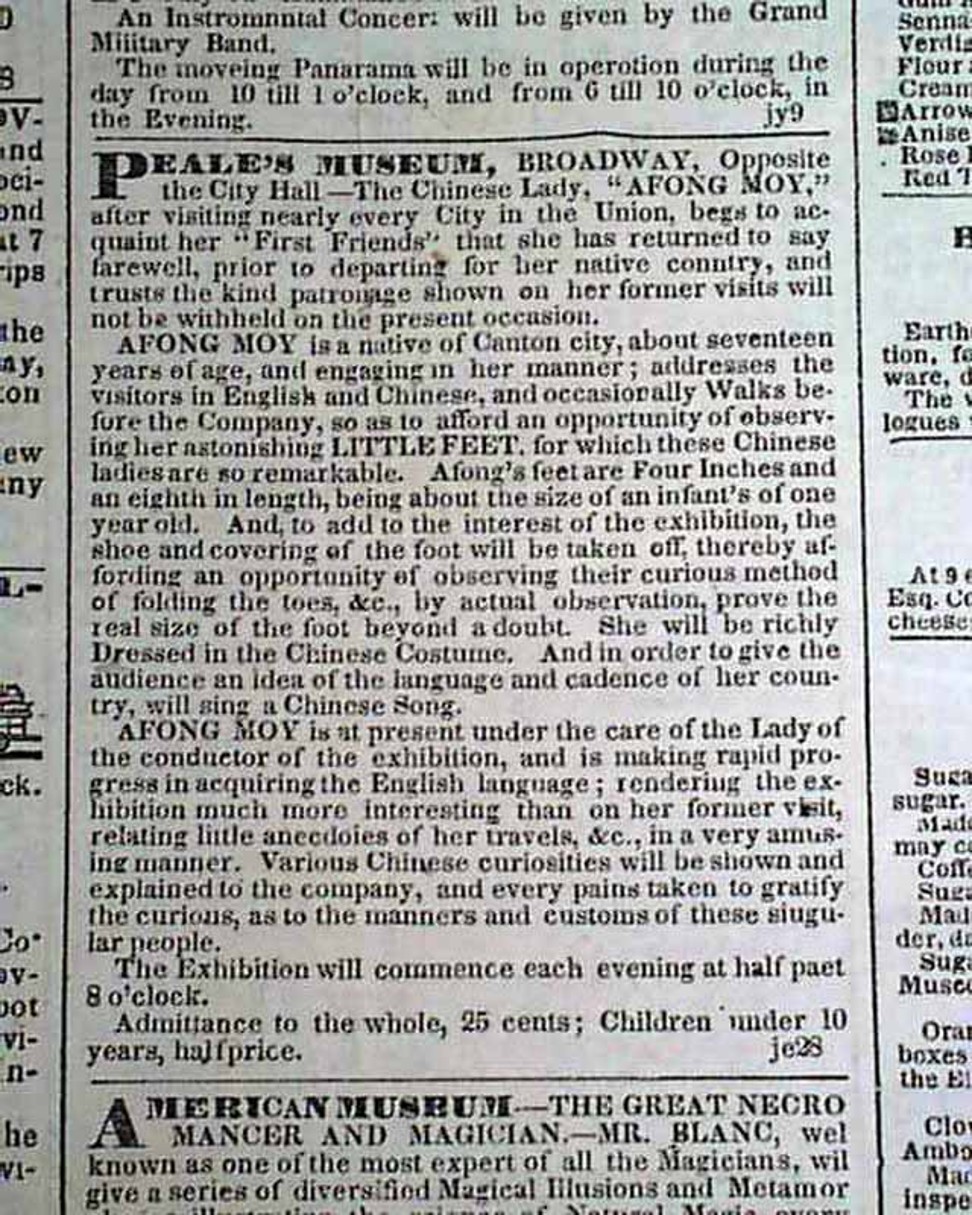

A newspaper clipping about Afong Moy.

While no solid impressions survive on how Moy herself felt about being objectified, there are hints. Davis writes that most disconcerting for her may have been “the attention paid to her by strange men in close proximity”, since women in China generally stayed out of public view. One business publication reported that “when some of them significantly ogled her through their quizzing glasses, we thought we saw on her brow, a frown of indignant rebuke”.

Not everyone was game to gawk at Moy. Some felt repulsed by what they regarded as a crass commercial venture that deprived her of dignity. An editorial in a New York City newspaper read: “We have not been to see Miss Afong Moy, the Chinese lady, nor do we intend to perform that ceremony to convert a lady into an exhibition. [It is] by no means to our taste.”

Later, Moy was able to communicate directly with audiences in English. She also sang, possibly the first performances in the United States of folk songs from her home province.

Cover of Nancy E. Davis’s The Chinese Lady.

She also emerged as something of a trendsetter – fashion plates depicted her “most becoming” hairstyle, stroked back from the forehead and knotted at the top of the head. It became a popular look widely adopted, especially by French women in New Orleans.

Moy’s last known chapter, unfortunately, relegated her to little more than a sensationalised caricature. From 1847, she was part of a circus sideshow, with PT Barnum pairing her with General Tom Thumb – his leading stage attraction – and joining her up with such figures as the Wonderful Monkey Man and the 430-pound (195-kilogram) Ohio Mammoth Girl. Her “differences” were mocked, and her personality was ridiculed.

A pamphlet advertising her oddity remarked that her “habits, everyday occupations and pursuits” were “opposite to all the received notions of every other civilised nation on the face of the earth”, and portrayed her as “vain, conceited, prideful and shallow”.

Animus towards outsiders was beginning to grow, and “a disdainful and derisive attitude toward the Chinese” had become standard. By 1850, Moy disappeared from Barnum’s spectacles, and she would be lost without further trace.

PT Barnum (left) and General Tom Thumb (stage name of Charles Sherwood Stratton) in a portrait circa 1850. Barnum founded Barnum & Bailey Circus, and for many years Tom Thumb was a popular dwarf performer in the circus.

Racial and ethnic tensions in Moy’s era resonate, depressingly, with American conditions today. The country she saw was gripped by nativism, as a fair chunk of Americans were wary of cultural and linguistic influences from overseas and advocated for tighter immigration and enfranchisement laws.

Davis emphasises that Moy, with her singular uniqueness, served as a cultural bridge between China and the United States, including in private and among elites. She met with President Andrew Jackson in February 1835, becoming, in the author’s words, the “first concrete example of China to a sitting American president”.

Portrait of Andrew Jackson, the seventh US president.

Davis’s book is a form of redress for a familiar injustice: the lives of the exploited, no matter how remarkable, rarely get remembered, much less told. Davis expresses hope that others can find out more about Moy, particularly from when history seemingly lost track of her, which would bring the “Chinese Lady” into greater relief.

If this happens, it would cast open wider a window into the treatment of women and racial minorities at tumultuous times in American history. And we might better grasp how attitudes and choices – about race, gender, culture and economics – shaped that society, and in turn help us assess the direction the country is going in today.

Asian Review of Books

This article appeared in the South China Morning Post print edition as: Significant, other: the first Chinese woman in America

A newspaper clipping about Afong Moy.

While no solid impressions survive on how Moy herself felt about being objectified, there are hints. Davis writes that most disconcerting for her may have been “the attention paid to her by strange men in close proximity”, since women in China generally stayed out of public view. One business publication reported that “when some of them significantly ogled her through their quizzing glasses, we thought we saw on her brow, a frown of indignant rebuke”.

Not everyone was game to gawk at Moy. Some felt repulsed by what they regarded as a crass commercial venture that deprived her of dignity. An editorial in a New York City newspaper read: “We have not been to see Miss Afong Moy, the Chinese lady, nor do we intend to perform that ceremony to convert a lady into an exhibition. [It is] by no means to our taste.”

Later, Moy was able to communicate directly with audiences in English. She also sang, possibly the first performances in the United States of folk songs from her home province.

Cover of Nancy E. Davis’s The Chinese Lady.

She also emerged as something of a trendsetter – fashion plates depicted her “most becoming” hairstyle, stroked back from the forehead and knotted at the top of the head. It became a popular look widely adopted, especially by French women in New Orleans.

Moy’s last known chapter, unfortunately, relegated her to little more than a sensationalised caricature. From 1847, she was part of a circus sideshow, with PT Barnum pairing her with General Tom Thumb – his leading stage attraction – and joining her up with such figures as the Wonderful Monkey Man and the 430-pound (195-kilogram) Ohio Mammoth Girl. Her “differences” were mocked, and her personality was ridiculed.

A pamphlet advertising her oddity remarked that her “habits, everyday occupations and pursuits” were “opposite to all the received notions of every other civilised nation on the face of the earth”, and portrayed her as “vain, conceited, prideful and shallow”.

Animus towards outsiders was beginning to grow, and “a disdainful and derisive attitude toward the Chinese” had become standard. By 1850, Moy disappeared from Barnum’s spectacles, and she would be lost without further trace.

PT Barnum (left) and General Tom Thumb (stage name of Charles Sherwood Stratton) in a portrait circa 1850. Barnum founded Barnum & Bailey Circus, and for many years Tom Thumb was a popular dwarf performer in the circus.

Racial and ethnic tensions in Moy’s era resonate, depressingly, with American conditions today. The country she saw was gripped by nativism, as a fair chunk of Americans were wary of cultural and linguistic influences from overseas and advocated for tighter immigration and enfranchisement laws.

Davis emphasises that Moy, with her singular uniqueness, served as a cultural bridge between China and the United States, including in private and among elites. She met with President Andrew Jackson in February 1835, becoming, in the author’s words, the “first concrete example of China to a sitting American president”.

Portrait of Andrew Jackson, the seventh US president.

Davis’s book is a form of redress for a familiar injustice: the lives of the exploited, no matter how remarkable, rarely get remembered, much less told. Davis expresses hope that others can find out more about Moy, particularly from when history seemingly lost track of her, which would bring the “Chinese Lady” into greater relief.

If this happens, it would cast open wider a window into the treatment of women and racial minorities at tumultuous times in American history. And we might better grasp how attitudes and choices – about race, gender, culture and economics – shaped that society, and in turn help us assess the direction the country is going in today.

Asian Review of Books

This article appeared in the South China Morning Post print edition as: Significant, other: the first Chinese woman in America

No comments:

Post a Comment