Solving a Paradox: New Younger Age Estimate for Earth’s Inner Core

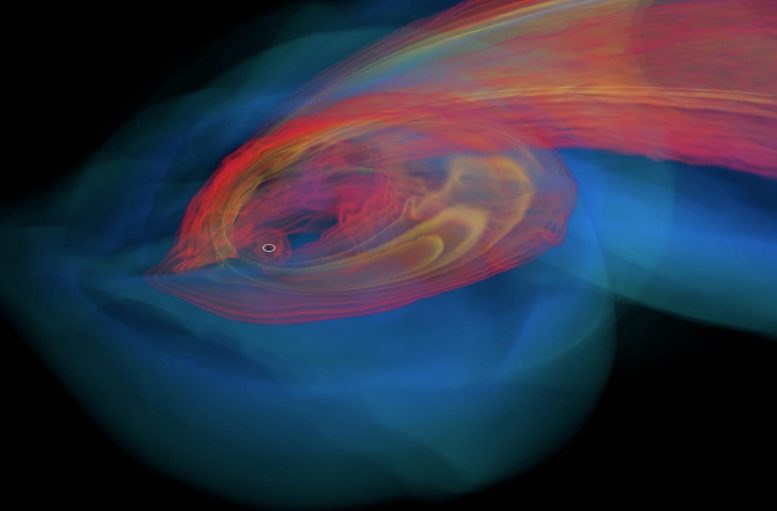

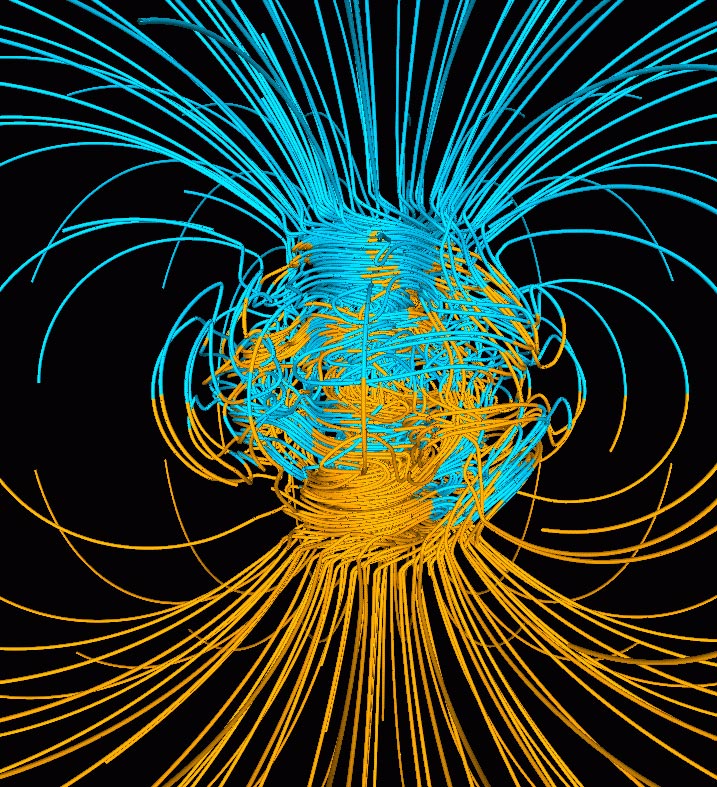

A computer simulation of the Earth’s magnetic field, which is generated by heat transfer in the Earth’s core. Credit: NASA/ Gary A.Glatzmaier

By creating conditions akin to the center of the Earth inside a laboratory chamber, researchers have improved the estimate of the age of our planet’s solid inner core, putting it at 1 billion to 1.3 billion years old.

The results place the core at the younger end of an age spectrum that usually runs from about 1.3 billion to 4.5 billion years, but they also make it a good bit older than a recent estimate of only 565 million years.

What’s more, the experiments and accompanying theories help pin down the magnitude of how the core conducts heat, and the energy sources that power the planet’s geodynamo — the mechanism that sustains the Earth’s magnetic field, which keeps compasses pointing north and helps protect life from harmful cosmic rays.

“People are really curious and excited about knowing about the origin of the geodynamo, the strength of the magnetic field, because they all contribute to a planet’s habitability,” said Jung-Fu Lin, a professor at The University of Texas at Austin’s Jackson School of Geosciences who led the research.

The results were published on August 13, 2020 in the journal Physical Review Letters.

The Earth’s core is made mostly of iron, with the inner core being solid and the outer core being liquid. The effectiveness of the iron in transferring heat through conduction — known as thermal conductivity — is key to determining a number of other attributes about the core, including when the inner core formed.

Over the years, estimates for core age and conductivity have gone from very old and relatively low, to very young and relatively high. But these younger estimates have also created a paradox, where the core would have had to reach unrealistically high temperatures to maintain the geodynamo for billions of years before the formation of the inner core.

The new research solves that paradox by finding a solution that keeps the temperature of the core within realistic parameters. Finding that solution depended on directly measuring the conductivity of iron under corelike conditions — where pressure is greater than 1 million atmospheres and temperatures can rival those found on the surface of the sun.

The researchers achieved these conditions by squeezing laser-heated samples of iron between two diamond anvils. It wasn’t an easy feat. It took two years to get suitable results.

“We encountered many problems and failed several times, which made us frustrated, and we almost gave up,” said article co-author Youjun Zhang, an associate professor at Sichuan University in China. “With the constructive comments and encouragement by professor Jung-Fu Lin, we finally worked it out after several test runs.”

The newly measured conductivity is 30% to 50% less than the conductivity of the young core estimate, and it suggests that the geodynamo was maintained by two different energy sources and mechanisms: thermal convection and compositional convection. At first the geodynamo was maintained by thermal convection alone. Now, each mechanism plays about an equally important role.

Lin said that with this improved information on conductivity and heat transfer over time, the researchers could make a more precise estimate of the age of the inner core.

“Once you actually know how much of that heat flux from the outer core to the lower mantle, you can actually think about when did the Earth cool sufficiently to the point that the inner core starts to crystalize,” he said.

This revised age of the inner core could correlate with a spike in the strength of the Earth’s magnetic field as recorded by the arrangement of magnetic materials in rocks that were formed around this time. Together, the evidence suggests that the formation of the inner core was an essential part of creating today’s robust magnetic fields.

Reference: “Reconciliation of Experiments and Theory on Transport Properties of Iron and the Geodynamo” by Youjun Zhang, Mingqiang Hou, Guangtao Liu, Chengwei Zhang, Vitali B. Prakapenka, Eran Greenberg, Yingwei Fei, R. E. Cohen and Jung-Fu Lin, 13 August 2020, Physical Review Letters.

DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.125.078501

DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.125.078501

The National Science Foundation and the National Natural Science Foundation of China supported the research.

The research team also included Mingqiang Hou, Guangtao Liu and Chengwei Zhang of the Center for High Pressure Science and Technology Advanced Research in Shanghai; Vitali Prakapenka and Eran Greenberg of the University of Chicago; and Yingwei Fei and R.E. Cohen of the Carnegie Institution for Science.