Jake Johnson, Common Dreams

December 22, 2021

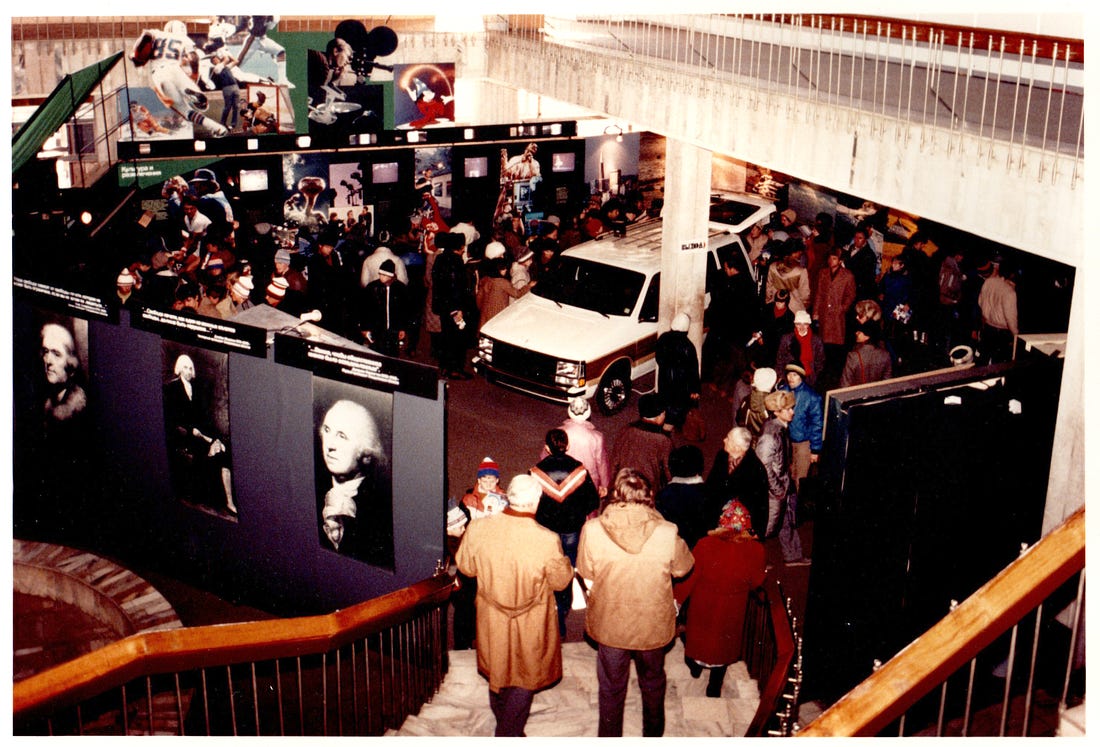

Kellogg's plant workers remain on strike after rejecting the company's latest contract offer (AFP)

Kellogg's workers' months-long strike officially came to an end Tuesday after union members voted to approve a new five-year collective bargaining agreement that includes an immediate wage increase of $1.10 per hour, a moratorium on plant closures, and a pension boost.

Anthony Shelton, international president of the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers International Union (BCTGM), called the new contract a "great workers' victory" and said that "solidarity was critical" to the achievement. Employees are expected to return to work on December 27.

"We're definitely stronger going back into that building than we were coming out."

"Our striking members at Kellogg's ready-to-eat cereal production facilities courageously stood their ground and sacrificed so much in order to achieve a fair contract," Shelton said in a statement Tuesday. "This agreement makes gains and does not include any concessions."

"Our entire union commends and thanks Kellogg's members," he continued. "From picket line to picket line, Kellogg's union members stood strong and undeterred in this fight, inspiring generations of workers across the globe, who were energized by their tremendous show of bravery as they stood up to fight and never once backed down."

Roughly 1,400 Kellogg's workers in four states—Michigan, Nebraska, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee—had been on strike since October 5, when cereal plant employees walked off the job in an effort to improve pay, benefits, and poor working conditions, a longstanding issue that deteriorated further amid the coronavirus pandemic.

Kellogg's workers have accused management of intentionally under-staffing the corporation's facilities—and forcing the remaining employees to endure brutally long shifts—to save money on pay and benefits, all while handing CEO Steve Cahillane nearly $12 million a year in compensation.

"The worst is when you work a 7-to-7 and they tell you to come back at 3 am on a short turnaround," Omaha BCTGM president Daniel Osborn, a Kellogg's mechanic, told Rolling Stone last month. "You work 20, 30 days in a row and you don't know where work and your life ends and begins."

"You sign on at a place like Kellogg’s, and you know they basically own your life," Osborn added. "You decide it is OK because you do it to support your family and give them a good life. But it has to be a relationship where you're valued, and the company doesn't look to squeeze out every last drop of profit at your expense."

Osborn told HuffPost on Tuesday that with the new collective bargaining agreement, "we were able to retain everything we had before that they were trying to take away, and we got some gains in there, too."

"We're definitely stronger going back into that building than we were coming out," he said.

A major dispute between workers and management has been the existence of a two-tiered compensation system that divides employees into "legacy" and "transitional" categories, with the latter receiving lesser pay and benefits.

Under the new contract, according to BCTGM, the two-tiered system would remain in place but it wouldn't be "permanent." The Washington Post reported that management "agreed to create an 'accelerated' path from one tier to the next," but some workers voiced concern that the new contract could further entrench the status quo.

"The agreement accomplishes something incredibly important: it breaks a cycle of concessionary bargaining."

"It's a trojan horse that's been given to us," one Kellogg's worker said at a rally in Battle Creek, Michigan last week, days before the vote on the contract was held.

C.M. Lewis, an editor of Strikewave and a union activist in Pennsylvania, argued in a series of tweets Tuesday that—all things considered—Kellogg's workers "got a better deal than if they hadn't struck."

"The agreement accomplishes something incredibly important: it breaks a cycle of concessionary bargaining that seemed irreversible even a few years ago. That's a big deal, and shouldn't be undersold," Lewis wrote. "Strikes work, but they don't work miracles. We need to be honest."

"Two-tier is still part of the contract. The road out of it is extremely limited," he added. "This isn't a defeat. It's not a slam-dunk victory. It's a victory that makes bigger victories possible. And we need to be okay with that ambiguity."

BCTGM, which did not release the vote totals for ratification, said the new contract includes a moratorium on plant closures through October 2026, "a clear path to regular full-time employment," "a significant increase in the pension multiplier," and "maintenance of cost-of-living raises."

"The BCTGM is grateful to AFL-CIO President Liz Shuler for mobilizing the AFL-CIO and its affiliates in support of our striking Kellogg’s members. Once again, President Shuler has provided highly effective leadership in support of the BCTGM and our members," Shelton said Tuesday. "The BCTGM is grateful, as well, for the outpouring of fraternal support we received from across the labor movement for our striking members at Kellogg's."

Part of a wave of recent labor actions across the U.S., the Kellogg's strike drew national attention as Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), President Joe Biden, and other prominent figures spoke out in defense of the workers.

"Last year, Kellogg's made over $1.4 billion in profits. It paid its CEO, Steven Cahillane, nearly $12 million in total compensation, a significant increase over recent years," Sanders wrote in an op-ed last week. "One of the reasons that Kellogg's had such a profitable year during this pandemic was the extraordinary sacrifices made by their employees who, in significantly understaffed factories, were asked to work an insane number of hours."

After Kellogg's announced earlier this month that it would move to permanently replace striking workers, Biden said in a statement that "such action undermines the critical role collective bargaining plays in providing workers a voice and the opportunity to improve their lives while contributing fully to their employer's success."

Trevor Bidelman, a Kellogg's worker and president of the BCTGM local in Battle Creek, told HuffPost that management's threat to permanently replace the unionized workers who walked off the job likely influenced the vote in favor of the new contract.

"The replacement threat was really the biggest piece," he said.