Parents, teachers concerned by Quebec's plan to reopen schools

Quebec says it still intends to reopen schools on Jan. 17, but some worry not enough has been done to ensure it will be safe for students.

Article content

Though they understand the importance of in-person learning for children, parents and teachers expressed concern Wednesday over Quebec’s plan to reopen schools in two weeks.

Advertisement

Article content

Despite the ongoing surge in COVID-19 cases, Quebec Education Minister Jean-François Roberge announced Wednesday the province still intends to have students back in class on Jan. 17.

But for some, reopening schools to students without added measures — such as improved ventilation or the N95 masks teachers have asked for — is too risky a move and one that could backfire.

“The risks are too high because of the sheer number of people in schools and the fact that we don’t have adequate protection,” said Lev Berner, a science teacher at Vincent Massey Collegiate in Rosemont. “If you get a high school student with Omicron inside a class, it is very unlikely that it doesn’t turn into something major.”

On Wednesday, Roberge said the province will prepare for the reopening by distributing 3.6 million rapid tests to elementary schools — five per month for every student — and adding 50,000 more carbon dioxide detectors in classrooms. Teachers and other school personnel will also be added to the priority groups that are eligible for PCR tests on Jan. 15, as will daycare staff.

Advertisement

But both Roberge and public health director Horacio Arruda said Quebec’s experts do not recommend having teachers wear N95 masks or equipping classrooms with air purifiers.

Asked why he believes it will be safe to send students back to class in two weeks, Roberge said being safe “doesn’t mean that no one gets the flu or gets COVID-19. It means we’re doing all we can and following the recommendations of our experts.”

Sylvain Martel, of the Regroupement des comités de parents autonomes du Québec, said many of the group’s members were surprised by the announcement and had expected the return to class to be postponed.

Martel noted that when Quebec announced it was closing schools in December , the province was recording roughly 3,000 COVID-19 cases a day. As of Wednesday, it was averaging more than 15,000 new cases per day.

And while vaccination rates are high across Quebec, they remain lower among young children who’ve only been eligible for the shot since November. Roughly 57 per cent of children aged five to eleven have received one dose of the vaccine.

Martel said to him, schools reopening feels oddly out of sync with the current situation in Quebec. And, he added, the few measures announced for the reopening on Wednesday did little to reassure worried parents.

“There seems to be a difference between what’s happening elsewhere in society and what‘s happening in the education sector,” Martel said, noting the curfew and other restrictions that are in effect. “We believe children belong in schools, but only when it’s possible to do so safely.”

For Dr. Earl Rubin, division director for pediatric infectious disease at the Montreal Children’s Hospital, the decision comes down to striking a balance, given how crucial in-person learning is for young children.

It also highlights how important it is for parents, grandparents and others who are around children to be adequately vaccinated, he said.

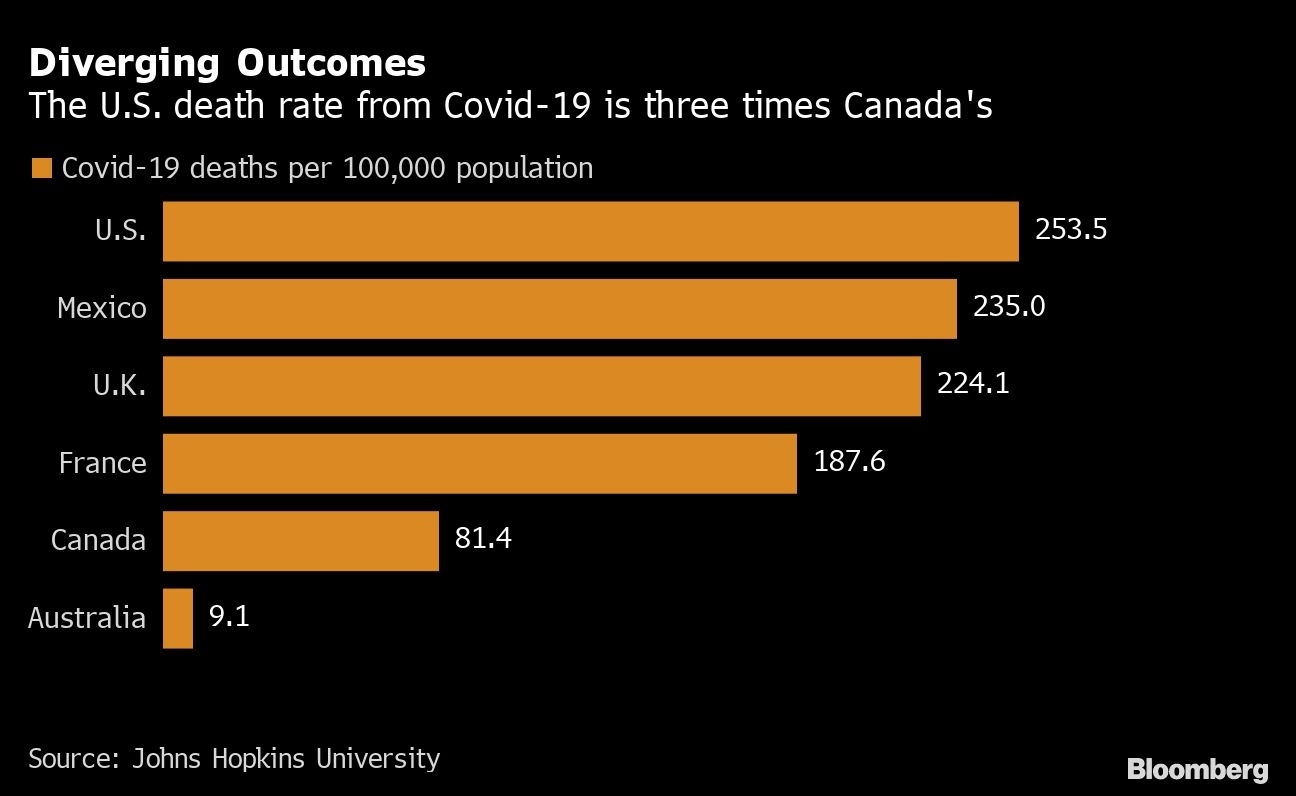

“If we can protect those who would need to be hospitalized so that the hospital system doesn’t crumble,” Rubin said, “then it’s a risk-benefit balance you have to look at.”

On the positive side, Rubin said the Omicron variant doesn’t seem to be causing severe illness at the moment, especially among children.

And, with the in-person return pushed back to Jan. 17, if people adhere to the restrictions in place, Rubin said hopefully any children who contracted the virus during the holidays won’t be bringing it back into the classroom with them.

Advertiseme

But given how transmissible the variant is, it’s likely the virus will “easily spread” once it makes it into a class.

“So we need to focus on protecting the people who are truly vulnerable,” Rubin said, “and do what we can to try to prevent it from coming in and spreading.”

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/HZJJCSKF2ZMHFK423ZQIHSXPYQ.jpg)